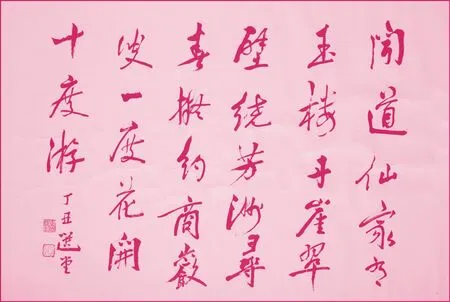

自由成就了他

——饶宗颐 Rao Zongyi: Freedom Made the Man

文/

不久前,他的去世引起了广泛的报道,特别是在学术界,人们不禁叹道:最后一位百科全书式的人物走了,一个时代结束了。

Not long ago, his death attracted widespread coverage, especially in academia, where people could not help but sigh: the last encyclopedic figure has gone, together with his era.

[2]他是饶宗颐。蹊跷的是,作为著名的学者,人们有时又很难把他归类于某个学科,因为他所涉及的学科和领域实在太广了。他曾对自己的学生说,你们要跟我学,到头来会很惨——弄到“无家可归”2 这里的“无家可归”显然是一种比喻,不宜简单地译成be homeless and without a place of refuge、get the key of the street、without a roof等,而实际指的是后面的“没有了固定学科”,故不妨译为out of scholarship。,即没有了固定学科。可是,现在有了结论:跨学术领域的旷世通才。

[2]Strangely, Mr.Rao Zongyi, famous scholar as he is, may sometimes be hard to classify into certain disciplines since his academic career had extended so broadly.He told his students,“If you want to follow me, you may end up miserably—find yourselves ‘out of scholarship’”.The world, however, has now concluded: he was a generalist of remarkable talent in modern times.

[3]在我看来,饶公所以能够取得如此成就,全在“自由”二字。

[3]It seems to me that his accomplishments relied on nothing other than“freedom”.

[4]首先是心灵上的自由。1917年他生于广东潮州的首富之家,却没有任何纨绔子弟的习气,而是倾心阅读。刚入初中,发现老师教的他全已学过,毫无兴趣,于是毅然退了学,埋头自家巨大的藏书楼里。看似孤独,但他却在书中徜徉于古往今来,极大满足了他的求知欲3 “满足求知欲”,一般可译成satisfy the thirst for knowledge、quench the thirst for knowledge等,但这里不妨将其变通为stimulated his thirst for knowledge,以更突出其对知识的兴趣。。“万古不磨意,中流自在心”。日后,他说,自己后来所以能做成点事情4 将此处的动宾结构短语变译为带有定语的名词短语a competent scholar,以更切其意。,就在于没有继续上学5 “上学”,通常译成go to school、attend school、be at school等,但这里根据其句式,不妨用schooling,同时将后面的“更因没有上大学”译为括号中的(let alone at a university),以作补充处理。、更因没有上大学。

[4]Most free of all was his mind.Born into the richest family in Chaozhou,Guangdong Province of China in 1917,he was free of any naughty child’s bad habits but enamored of reading.Entering junior high school, he found what the teachers taught was nothing newer than the books he had already read at home,which bored him to death.Determinedly,he dropped out of school and buried himself in his family’s huge library.The now-lonely figure wandered through books from ancient to modern times,which greatly stimulated his thirst for knowledge.“My free mind remains as it is despite the abrasion of the ages”, as he later put it,“and my absence of schooling (let alone at a university) has shaped me as a competent scholar”.

[5]在学术上,他也毫无学科的禁忌——从上古到明清,从国学到西学,从研究到艺术……在书林学海中,他独来独往,任意驰骋6 “任意驰骋”字面意思be free to gallop、any ride,若译成roamed willfully / single handedly,又显重复,其实roam即可表明其意。。他去日本发掘罕见甲骨文,写出惊世著作;赴印度研究梵文、佛学,被特聘为学术研究员;到法国开拓跨文化的比较,获得“儒林汉学特赏”(相当于西方汉学诺贝尔奖)。

[5]Academically, he was not bound by any boundaries—he roamed single handedly from the palaeolithic to the Ming and Qing Dynasties, from Chinese learning to Western culture, from research to artistic activities… In the vast ocean of knowledge, he traveled tens of thousands of miles alone and freely: in Japan he explored rare oracles in writing an outstanding book; in India he studied Sanskrit and Buddhism and was appointed as an invited researcher;in France he developed comparative cross-cultural studies and was rewarded the Special Sinology Prize (known as the Nobel Prize in Sinology).

[6]若以现代学科而论,饶公的学术成就,似可主要纳入下述领域:史学、甲骨学、考古学、金石学、楚辞学、敦煌学、哲学、宗教、词学、目录学、书画、音乐等。但他自己并不这样认为,而是一向主张打通学科,左右逢源;以学问积淀艺术,用艺术滋补学问。著名的西泠印社,一向秉承艺术与学养并举的传统,于是推选饶公做社长,非他莫属7 “非他莫属”,似可译成nobody else is worthy except him、he could be the next big thing等,但这里可稍加变通,点明为as its perfect president。。同时,他还通晓英语、法语、德语、日语、印地语、梵文、阿拉伯语文、巴比伦古楔形文字等。

[6]According to modern disciplines,Mr.Rao’s academic achievements may be classified into the following fields:history, oracle-bone inscriptions, archaeology, epigraphy, songs of the south,studies of the Dunhuang Caves, philosophy, religion, Ci poetry, bibliography,painting and calligraphy, music and so on.However, he himself would disagree since he always promoted an inter-disciplinary approach to integrating resources in research, removing barriers between learning and art so as to mutually benefit each other.The well-known Xiling Seal Engravers’ Society, forever upholding the tradition of endorsing learning and art on an equal footing, selected Mr.Rao as its perfect president.Meanwhile, he was also proficient in English, French,German, Japanese, Hindi, Sanskrit, Arabic and ancient Babylon cuneiform.

[7]就性格而言,饶公身上充满了好奇心、孩童心和自在心8 这三“心”的核心是“自在心”,故不宜并列译出,而是将其融化在句子中。。他在学问中寻找乐趣,在玩笑中讲究学问;他少年老成,作文如长者,老来又活泼风趣,酷似顽童;他因境而形9 “因境而形”包含了后面“在天为云,在地为水”的内容,故可不必译得太“实”,如he could become a cloud when in heaven and water on earth等,可统而化之为:He was very open to changes in ambience and progress.,在天为云,在地为水,随心所欲不逾矩。他不计功名,却功成名就。

[7]In terms of personality, Mr.Rao,filled with child-like curiosity, had always followed his own free will.He found fun in learning and cracked jokes with knowledge.He produced mature writings in his childhood, and became light, lively and funny when he got old.He was very open to changes in ambience and progress; in a sense, he never refused whatever his heart desired for the right cause.He couldn’t have cared less about honor and fame, but has been widely recognized for his extraordinary achievements.

[8]在客观上,还要归结于他所处的自由学术环境。1949年,他阴差阳错10 “阴差阳错”有多种译法,如a strange combination of circumstances、by accident、for all the wrong reasons、it’s a rearrangement of yin and yang 等,但此处分解成了accidental和Blessed by God。,因一场大病滞留、定居在了香港,从此躲过了内地发生的一系列政治运动和文化浩劫。人算不如天算。

[8]Objectively, he owed much to his free academic environment.In 1949, an accidental but serious illness hampered his journey home and made him a citizen of Hong Kong.Blessed by God, he was forever immune from a series of political turmoils and cultural catastrophes happening on the Chinese Mainland.

[9]当年,只有小学文凭的他,却受聘于各著名大学,这恐怕也是当今中国教育体制所不能允许的。在这个意义上,他的成功又不是可以简单复制的。11 此句译文的词序做了较大调整,即将其提前译出,而将上句的“当今中国教育体制所不能允许的”置后处理,以更加通顺、自然。

[9]In those years, with just a primary school certificate, he could be hired by several prestigious universities as a lecturer and professor.It would be extremely difficult for his success story to be simply replicated, as today China’s educational system would hardly permit such a case to happen.

[10]回看中国现代文化史,上一位这样的学术通才,要追溯到在91年前12 此处在译文中与原文中括弧里的“1927年”互换了位置,才更符合原义,更易表达,显出中英文的不同特点。(1927年)去世13 “去世”通常意义上是passed away、died、demised、departed、went aloft、went off等,但这里似乎是“反其义”而译为in his final year of life,以更宜与“上一位这样的学术通才”相关联和比较。的王国维先生。陈寅恪称赞他的“自由之思想,独立之精神”。两位大师可谓心犀相通。饶公的百年寿命整是王公的一倍,学术成果自然更加丰厚;但在治学方面,饶公既有“古法”,又有“新意”14 这里没有按通常意义上“既有……又有……”的句式译出,而是据其语境,将其整合为 refreshing ideas on classical scholarship,并将词序调整,以更易表述。,实乃接续了王公的潇洒风范,并且将其发挥到了极致,令后人难以企及。

[10]In retrospect, the last such academic talent in modern China’s cultural history can be traced back to 1927 (91 years ago) when Mr.Wang Guowei,in his final year of life, was praised by Chen Yinque for his“freedom of thought and spirit of independence”.The two masters’ hearts beat in common.Surely, Mr.Rao’s academic achievements are far more abundant than Mr.Wang’s, given his life-span was twice as long; in approaching learning, however, Mr.Rao had thoroughly inherited Mr.Wang’s unconventional legacy—constantly refreshing ideas on classical scholarship—and used his talents to the utmost, which will be hard to match for generations to come.