The Logic of Legal Narrative1

Yicun Jiang

Shandong Technology and Business University, China

1. Legal Discourse in Narrative Semiotics

Narrative semiotics, as championed by A. J. Greimas and other members of what is known as the Paris School Semiotics (Perron & Collins, 1989), has its unique way of interpreting narrative texts. As contended by Martin and Ringham (2006, p. 2), the Paris School is“concerned primarily with the relationship between signs and with the manner in which they produce meaning within a given text or discourse”. Thus, the importance of this school is attached not only to the theories but also to their application as methodological tools for text analysis. In fact, Greimas’s ambitious semiotic project purports to apply this approach to all possible texts regardless of the cultural and stylistic differences, one of which is legal narrative. In 1976, Greimas and Landowski’s collaborated paper entitled“The Semiotic Analysis of Legal Discourse: Commercial Laws That Govern Companies and Groups of Companies”, initiated the application of narrative semiotic theory to the study of legal documents. In that paper, they defined “legal discourse” as follows:

The very expression “legal discourse” already contains a certain number of presuppositions that need to be clarified. First, it suggests that by legal discourse one has to understand a subset of text that are part of a larger set, made up of all the texts that appear in any natural language(in our case, French). Second, it indicates that we are dealing with discourse, that is to say, on the one hand, the form of its organization, which includes, in addition to phrastic units (lexemes,syntagms, utterances), transphrastic ones (paragraphs, chapters, or, finally, actual discourses).Third, qualifying a subset of discourse as legal in turn implies either the specific organization of the units constituting it or the existence of a specific connotation underlying this type of discourse, or, finally both at the same time. (Greimas, 1990, p. 105)

As stated above, Greimas considered legal discourse as a subset of the larger set,i.e., the natural language. On this point, Greimas holds the same idea with the American forensic linguist, Peter Tiersma (1999), who also does not agree to divorce legal language from natural language. In the aforementioned paper, Greimas (1990, p. 105) also elaborated his meaning of the “subset”:

To say that legal discourse is a subset of a set, the infinite text unfolding in French or in any other natural language, amounts to admitting that, while incorporating certain properties that distinguish it from other discourses taking place in French, it nevertheless possesses everything making it possible to define it as discourse in a natural language. From this point of view, its status is not fundamentally different from literary, political, or economic discourses produced in French.

According to Greimas (1990, p. 105), “general and specific properties of legal discourse” can be deduced from the general properties of natural language, and legal discourse can be recognized as such if it has a certain number of “recurring structural properties” (Greimas, 1990, p. 107) that may differentiate it from both everyday discourses and other secondary discourses that have other specific properties.Furthermore, the analysis of a specific legal text, such as a case report, “presupposes reflecting on the status of legal discourse as a whole”, if we have, at our disposal, “a certain number of operational concepts clarifying its properties” (Greimas, 1990, p. 105).For Greimas, narrative semiotics can provide such kinds of operational concepts for the analysis. In fact, even from a stylistic perspective, narrative semiotics is also quite applicable for interpreting legal documents, for most of these documents are inherently narrative as stated by Tiersma (1999, p. 147) in the following remark:

Trials are very much about stories or narratives. A lawsuit typically begins after a series of events has caused something wrong or illegal to happen to someone, and for which the injured person seeks a remedy. The person asking the court for a remedy therefore comes telling a tale.Before continuing with a description of how the plaintiff’s story unfolds during the course of the trial, we set the stage by briefly considering the structure of narratives.

2. The General Structure of a Case Report

Normally, at the end of each court case, the judge presents an oral judgment and writes up a case report to conclude the case (Gibbons, 2003, p. 134). Case reports play a vital role in the Common Law system as records of judgments that can be used as a foundation for subsequent judgments, which constitutes the so-called “judge-made law”. Thus, case reports have become an important genre of legal texts (Gibbons, 2003). Indeed, case reports as typical legal narrative have every general feature of legal discourse and at the same time have specific features of their own. According to Gibbons (2003), a case report contains two main sections, the prefatory material and the judgment itself, in which the main information is assembled and therefore is the most important part in the report. The detailed structure of a case report is concluded as follows by Gibbons (2003, p. 160):

Case report genre

Prefatory Material

Heading

Name of case

Court name

Reference number

Name(s) of Judge(s)

Date(s)

Keyword summary

Law & Procedure

(Evidence)

(Words and Phrases)

Summary of judgment

In English

Summary (Obiter) (Per curiam)

In Bahasa Malaysia

Summary (Obiter) (Per curiam)

(Appeal)

From/To

(Notes)

(Cases)

(Legislation/Regulation)

(Previous lower court)

Names of counsel

(Date)

Judgment

Orientation

Participants

Previous litigation

(‘Facts’)

[narrative genre]

Issues

Counsel’s argument

Judge’s interpretation/reasoning

Decision

(Legal issues)

Finding

Verdict

(Penalty/Award)

Costs

(Obiter)

The case report chosen for analysis in the present paper is about a breach of contract suit. The trial happened in the territory of the United States and the trial court was an American state-court called “the Court of Appeals of Texas”. Phyllis Locke entered into a contract with Mistletoe Express Service, but later Mistletoe canceled the contract and failed to terminate it by thirty-day written notice. As a result, Locke brought Mistletoe to court, which made a judgment where the damage of Locke was considered as $19,400.00.However, Mistletoe saw the judgment as an adverse one, and then it appealed to the Court of Appeals. The judge of the Court of Appeals made a final judgment and reduced the damage to $13,000.00. The case report was written by the chief judge, Judge Cornelius.

3. The Surface Structure

In narrative semiotics, the surface structure refers to the level of meaning in a text that is more general and abstract than the discursive manifestation (Greimas & Courtes, 1982). It consists of a “story grammar or surface narrative syntax, a structure that, according to the Paris School, underpins all discourse, be it scientific, sociological, artistic, etc.” (Martin &Ringham, 2006, p. 12). The core of the surface structure is the narrative grammar, which is independent from the discursive instruments that are adopted to manifest it. To be more specific, it contains two fundamental narrative models: the actantial narrative schema and the canonical narrative schema, which “jointly articulate the structure of the quest or, to be more precise, the global narrative program of the quest” (Martin & Ringham, 2006, p.12). Thus, this section will concentrate on demonstrating the surface structure of the case report through examining the above two narrative models.

3.1 Segmentation

To facilitate the analysis, we divide the case report into two parts according to the transformation of time, space, and subjects. The first part is from “Phyllis Locke, doing business as Paris Freight Company…” to “The court entered judgment for that amount,plus prejudgment interest and Attorney’s fees of $2,000.00”. The second part is from“Mistletoe’s sole contention is that the trial court should have granted it a directed verdict or judgment notwithstanding the verdict…” to the end. On the part of time, the clear marks,such as October 1, 1984 and June 15, 1985, have repeatedly appeared in the first part of the case. In this part, the past tense is adopted by the judge to indicate that he/she is depicting the events that happened in the previous court. In the second part of the case report,however, there are no clear marks of time, and the present tense is adopted to describe the events that occurred in the court of appeals, which is considered as being “now” in the present report. The application of different tenses indicates the transformation of space, i.e.,the changing of courtrooms and locations, from the former court to the court of appeals.On the part of subject transformation, the subject of quest in the first part is Phyllis Locke,while the subject of quest in the second part converts to Mistletoe Express Service.

Moreover, it is worth noting that the technique of flashback is adopted at the beginning of the passage, i.e., the first sentence and paragraph state the events that occurred in the second part of the report. In the first paragraph, the subject-actant is Mistletoe, contrasting the subject-actant “Locke” in the subsequent paragraph. Thus,the change of subject-actants in the first two paragraphs indicates the segmentation of the whole report. Logically, the first paragraph should be put back in the place where it belongs, that is, the sixth paragraph before the sentence “Mistletoe’s sole contention is that the trial court should have granted it a directed verdict or judgment notwithstanding the verdict, because there is no evidence to support the damages which the jury awarded…” and the first part of the report should begin from the second paragraph. Besides, the first sentence of the case report implies the existence of a former court. The verb “appeal”in the sentence is a dynamic predicate designated by Function (symbol: F). Therefore,we have the semantic kernel or the simplest narrative statement for the whole report: F:appeal (Mistletoe).

3.2 The surface structure of the first part

We start the analysis with examining the actantial narrative schema of the first part:

Subject:Phyllis Locke

Object:To win the trial and get the due damage pay from Mistletoe Express Service.

Sender:The sender is a combination of three factors: the fact that the subject has undergone damages, the existence of the contract law, and the subject’s legal awareness.

Receiver:Phyllis Locke

Helper:The contract law and Locke’s lawyer, who, although not present, was implied in the report.

Opponent:Mistletoe Express Service

In this part, the subject of the narrative is Phyllis Locke. The subject-actant involved in social actions (making the contract and doing business) with the opponent—Mistletoe Express Service—underwent some damages caused by the opponent’s breach of the contract. Aware of the existence of the contract law and that the legal rights of victims are protected by the law, the subject brought the opponent to court. The liability of the narrative in the indictment is quite crucial for the judgment, for the jury usually “make their decision on the basis of whose story is most convincing, in terms of its completeness,consistency and the credibility of supporting witnesses” (Gibbons, 2003, p. 156). Finally,the jury made a verdict that the opponent should pay the damage for the subject, and a judgment is thus made by the judge. Next, we examine the canonical narrative schema:

Contract:

Locke had the legal awareness to protect her benefits when she recognized that Mistletoe had broken the contract, and the role of Locke turned from a party of the contract into a victim. As a victim, she wanted to bring Mistletoe to the court to get her compensation, so as to transform the regulations in contract law into real legal actions. At this time, she obtained the modality of “wanting-to-do”, and a “contract” was made between Locke and the court on this case. Thus, Locke began her quest of claiming her damage.

The qualifying test (the stage of competence):

The contract law protects victim’s benefits and lawful rights. Locke’s rights had been under protection at the time when she entered into the contract with Mistletoe. From the case report, we know that Locke followed the contract from the beginning to the end.Therefore, when Mistletoe broke the contract, Locke had a good reason to claim for her damage. In this situation, Locke has acquired the competence to take all related legal actions and has the modality of “knowing-how-to-do” which constitutes a key component of narrative competence” (Martin & Ringham, 2006, p. 112). As contended by Martin and Ringham (2006, p. 112), the subject of a quest “will need to acquire the necessary knowledge and skills (=knowing-how-to-do) to achieve his goal”, if he/she is to pass an examination with honors. In other words, the subject should show his/her competence of finishing the quest before proceeding to the next stage.

The decisive test (the stage of the performance):

When Locke found out that she had got the “competence” of claiming the damage,she finally brought Mistletoe to the court. In this way, she has the modality of “beingable-to-do”. The real legal actions of Locke generated by her legal awareness are the realization of this modality.

The glorifying test (sanction):

In the first trial, the judge believed that the damage of the victim was $19,000.00 USD plus prejudgment interest and Attorney’s fees of $2,000.00. This legal decision is obviously recognition for Locke and a punishment for Mistletoe.

3.3 The surface structure of the second part

In the second part of the case report, the transformation of the subjects is quite obvious.The judge introduced the reason why Mistletoe appealed, and took account of the relative regulations of the case and the restatements it could use for reference. In the end of the report, a final judgment is made on the basis of the judge’s legal reasoning. The actantial narrative schema of the second part is shown as follows:

Subject:Mistletoe Express Service

Object:To reduce the damage to a reasonable and acceptable amount

Sender:The legal awareness of the subject who cannot accept the damage amount decided by the last court

Receiver:Mistletoe Express Service

Helper:The helper here is Mistletoe’s lawyer in the appeal case. Although it is not mentioned in the report, we cannot deem it absent.

Opponent:The former judgment and Locke

Then, we turn to the canonical narrative schema:

Contract:

Mistletoe found the damage made by the court unacceptable and decided to appeal. At this stage, Mistletoe got the modality of “wanting-to-do” and made a “contract” with the Court of Appeal to start the quest.

The qualifying test (the stage of competence):

Mistletoe felt that the damage decision made by the judgment was not reasonable and that their party had the right to appeal. At this stage, the subject has the modality of“knowing-how-to-do”.

The decisive test (the stage of the performance):

Mistletoe thus appealed according to relative legal regulations and solicited the court to review the amount of the damage decided by the previous trial. By doing this, the subject has the modality of “being-able-to-do”.

The glorifying test (sanction):

The Court of Appeals finally reduced the former damage by $6,000.00, i.e., from$19,000.00 to $13,000.00. The reduction has fulfilled (at least partially) Mistletoe’s request. In other words, Mistletoe is affirmed and awarded by the Court of Appeals.

On the basis of the above analysis, we hereby obtain a generalized actantial narrative schema for all case reports as a genre of legal narrative:

Subject:The indictor

Object:To win the suit

Sender:The legal system and people’s legal awareness

Receiver:The indictor

Helper:The indictor’s lawyer/lawyers

Opponent:The indictee

As shown in the above analysis, the case report exhibits a panorama of the whole series of events. If we see the whole event as a syntagmatic structure, we can have the syntagmatic transformation on the narrative level, i.e., a narrative syntax, and it goes on like this: contract—competence—performance—sanction. The unfolding of the event as a syntagmatic structure thus reveals the narrative logic of the case report.

4. The Deep Structure

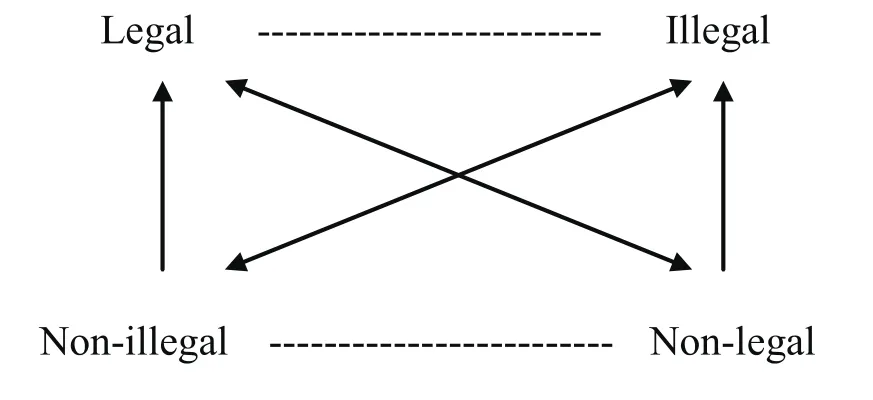

In traditional structuralism, meaning is generated in form of binary opposition, and Greimas (1987) further developed it into the form of a square that contains four items,which, in narrative semiotics, is considered the original birthplace of meaning and thus constitutes the core of the deep structure of meaning. The manifestation of the four items in the semiotic square is as follows:

The enumeration of the advantages of the square can begin at once with the observation that it is a decisive enlargement of the older structural notion of the binary opposition: S1 versus S2 is typically such a kind of opposition. The square reveals itself to encompass more than two values and relations. Accordingly, three semiotic relations have been established in the square: the relation of contradiction is established between S1 and -S1, and the same is the one between S2 and -S2; the relation of contrariety is built by S1 and S2 on the one hand and -S1 and -S2 on the other; the relation of implication is established between S1 and -S2 on the one hand, and S2 and -S1 on the other, which is to say S2 implies -S1 and S1 implies -S2, and vice versa (Greimas, 1987, p. 49). In narrative semiotics, any individual mind is and will always exist in such a way and this deep signified structure of meaning is the basic condition for the existence of any sign.For Greimas (1987), semiotic square is a fundamental base that a discourse lives by.

Compared with the surface structure of the case report, the deep structure can reveal more of its underlying logical structures, one of which is actants’ behaviors and actions.Generally speaking, people’s behaviors, especially in the scope where the legal documents can be effective, can be divided into four categories as being legal, illegal, non-legal and non-illegal. Thus, actions or behaviors of the subject in a quest can be manifested in a square as follows:

From the fulfillment to the breach of the contract, the transformation of Mistletoe’s actions from legal to illegal is a gradual process. In a broader sense, “non-legal” and “nonillegal” serve as two contrasting items to compensate the shortage of law that merely includes two regular items: legal and illegal. Indeed, there is a lot more in our life than law,and in real life people are not living in the framework of binary opposition as being either“legal” or “illegal”. The items of non-legal and non-illegal contain all other behaviors that cannot fall into the category of either legal or illegal. In other words, one’s action can be either legal, or non-illegal, or non-legal, or illegal. “Legal” and “illegal” manifest the existence and the power of law, while non-illegal and non-legal reveal the absence or virgin soil of law. Therefore, what the law makers are doing is to explore the virgin soil and to fill up where the law is absent. Theoretically, the list of behaviors that a legislator is attempting to regulate is supposed to “cover the totality of the justiciable universe” (Greimas, 1990, p.110). According to Greimas, two procedures are possible: one considers “only prescribed behaviors as legally existent”, while the other considers “all forbidden behaviors as legally nonexistent” (Greimas, 1990, p. 110). In other words, echoing the categories of “legal” and“illegal”, there are “prescriptions” and “interdictions” in real legal practice, on the basis of which we may get the following elementary model:

Here, the “prescription” refers to the category in which, so long as people follow the regulations, their behaviors can be protected by the law, while the “interdiction” refers to the category in which people’s behaviors would be punished because of their violation of law. In the case report we analyzed, Mistletoe followed the contract at the beginning,but ended up breaking it. In other words, there is a transformation from prescription to interdiction in Mistletoe’s behaviors. Like non-legal and non-illegal, “non-prescription”and “non-interdiction” represent the categories that cannot be included in “prescription”or “interdiction”.

In a global sense, this case report reflects a dynamic relationship between law (ought to be) and reality (to be) which, if we add two more items to it, i.e., non-law (not ought to be) and non-reality (not to be), can be visually manifested in the following square:

As shown above, the legal text can be reduced to a signified structure that includes“reality”, “non-law”, “non-reality”, and “law”. In other words, the procedure of gradual transformation from “reality” (to be) to “law” (ought to be) constitutes the deep signified structure that underlies the whole text. The left side of the square represents legal system,while the right side of the square represents the real world. In fact, the meaning of legal text is a dynamic possibility, and it is the deep structure manifested through the above square that transforms the possibility to reality. It is also in this way that case report is generated from the four elements in this square. To some extent, it is safe to say that this specific semiotic square underpins all possible legal discourses.

Through the previous analysis of the surface structure, we have obtained the narrative syntax of the case report: contract—competence—performance—sanction. Such narrative logic may be visualized in form of semiotic square, although in a modified version. To be more specific, the syntagmatic transformation of the events in the case report can be presented according to the syntagmatic order that takes into account the temporal arrangement of the terms and the relation of implication between them: (A>C)→(A>C)(see what each character or sign stands for below). The two implications form the deixis in the following square:

A: the breach of the contract

C: the negative communication

C: the positive communication

A: the establishment of another contract

>: the relation of implication

Tests 1, 2, 3: the three tests in the canonical narrative schema

According to the logic of the discourse, we can get the syntagmatic structure and read the simple structure as a “then” and “because” relation: Because A, C happens; and then,because C, A happens (Budniakiewicz, 1992, p. 210). Therefore, the three tests we have explained in canonical narrative schemas form a logically consistent process. In this way,actions of the two courts in the case report can be connected together. In other words,the whole process is a continuum, similar to semiosis, which contains similar events in paradigmatic axis. Actions of the actants in the two canonical narrative schemas can thus be reconnected in the following modified squares:

In the first quest, a contract is established as the “Final 1”. The “Initial 2” in the second square challenges the “Final 1” in the first square, which means another breach of the contract and also the beginning of another quest. The whole event ends with the establishment of the “Final 2”. In this way, the two quests realized through two different courts with different subjects in the case report are logically linked together. This also shows that the two meaning structures (surface and deep) are logically consistent, and the deep structure underpins the surface one.

5. Further Discussion

Normally, the judge in a legal system has the power to make a decision for a law case and is authorized to complete the formal case report. Thus, the judge takes part in legal activities and makes decisions by legal reasoning. In this sense, we also notice, besides the surface and deep structures analyzed above, another quest in this report: a quest of the judge who is also the narrator. The actantial model of the quest is stated as follows:the sender is the appealing party Mistletoe, the receiver and subject is the judge of the Appeal Court who is the writer of this case report, the object is to make a legal judgment,the helper is the law and the legal system, and the opponent is the judgment made by the previous court. In other words, the judge has also gone through a quest, and the final decision is also a legal “doing” rather than “being”. Thus, one important feature of the case report as a legal narrative lies in its dual model on the actantial level.

Another important feature in Anglo-American legal system or the Common Law system is that some cases, especially the classic and typical ones, may serve as a reference for future law cases and for the making of legal restatements. Such a phenomenon is famously known as the “judge-made law”. In fact, former cases that are in the same nature with the present case at hand will truly affect the judge’s reasoning in making a legal decision. Thus, the former case of the same character can serve as the pre-understanding of subsequent ones. In this sense, the end of one case can be seen as the beginning of another, hence the formation of a semiotic continuum in a legal system—legal semiosis.It needs to be pointed out that the process of legal semiosis is dynamic rather than static.While the judge uses former case reports as a reference for his judgment, the final decision is also made by the combination of the reference and the judge’s own reasoning on the basis of the new context of a case. Any single case has its unique features that make it distinct from other ones. Therefore, although some cases might fall into the same category, the final decisions of these cases always have some differences. The latter ones can correct the weak points erected in the former ones and it is in this way that the legal system is improved, which reveals the mechanism of the judge-made law system.

Note

1 This study is sponsored by the Youth Project (Project No.: 2013QN086) at Shandong Technology and Business University entitled “A Semiotic Study of Qian Zhongshu’s Metaphor Theory”.

Budniakiewicz, T. (1992).Fundamentals of story logic: Introduction to Greimassian semiotics.Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Gibbons, J. (2003).Forensic linguistics: An introduction to language in the justice system. Oxford:Blackwell Publishing.

Greimas, A. J. (1987).On meaning: Selected writings in semiotic theory(Trans., P. Perron & F.Collins). London: Frances Pinter.

Greimas, A. J. (1990).Narrative semiotics and cognitive discourses(Trans., P. Perron & F.Collins). London: Frances Pinter.

Greimas A. J., & Courtes, J. (1982).Semiotics and language: An analytical dictionary(Trans., L.Crist, D. Patte, J. Lee, E. McMahon II, G. Phillips, & M. Rengstorf). Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Martin, B., & Ringham, F. (2006).Key terms in semiotics. London/New York: Continuum International Publishing Group Ltd.

Perron, P., & Collins, F. (Eds.). (1989).Paris School Semiotics. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Tiersma, P. (1999).Legal language. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

(Copy editing: Alexander Brandt)

Appendix

MISTLETOE EXPRESS SERVICE vs. LOCKE1Taken from: Barnett, R. E. (2003). Contracts: Cases and Doctrine. Beijing: China CITIC Press,pp.120-122.

Court of Appeals of Texas, Texarkana,

762 S.W.2d 637(1988)

Cornelius, C. J.

Mistletoe Express Service appeals from an adverse judgment in a breach of contract suit.

Phyllis Locke, doing business as Paris Freight Company, entered into a contract with Mistletoe on October 18, 1984, which provided that Locke would perform a pickup and delivery service for Mistletoe at various locations in Texas. The contract term was one year from October 1, 1984. At the expiration of the initial term, the agreement would continue on a month-to-month basis until either party terminated it by thirty-day written notice.

In order to perform her contract, it was necessary for Locke to make certain investments and expenditures. In uncontroverted testimony, she stated that she spent$3,500.00 for materials to build a steel and pipe ramp and $1,000.00 for dirt work. She also borrowed $15,000.00, with which she purchased two vehicles for $9,000.00 and paid$6,000.00 for starting-up expenses. She testified that she would not have done any of these things had she not made the contract with Mistletoe. Locke’s company never made a profit, although the losses decreased each month while the contract was in force.

On May 15, 1985, Mistletoe noticed Locke that it planned to cancel the contract effective June 15, 1985. Locke closed her business and sold the vehicles for $6,000.00,taking a loss of $3,000.00. At the time of trial, Locke still owed $9,750.00 on her$15,000.00 loan, and had paid $2,650.00 in interest. She testified that the customized was worth $5,000.00 as scrap. She considered the $1,000.00 expended for dirt work a lost expense.

The jury found Locke’s damages at $19,400.00. The court entered judgment for that amount, plus prejudgment interest and Attorney’s fees of $2,000.00.

Mistletoe’s sole contention is that the trial court should have granted it a directed verdict or judgment notwithstanding the verdict, because there is no evidence to support the damages which the jury awarded. The gist of the argument is that the victim of a contract breach is only entitled to be placed in the position he would have been in had the contract been performed, and therefore Locke could only recover the profits she lost by reason of the breach.

It is a general rule that the victim of a contract should be restored to the position he would have been in had the contract been performed. Determining that position involves finding what additions to the injured party’s wealth have been prevented by the breach and what subtractions from his wealth have been caused by it. 5 Corbin on Contract 992(1964). While the contract requires a capital investment by one of the parties in order to perform, that party’s reasonable expectation of profit includes recouping the capital investment. The expending party would not be in as good a position as if the contract had been performed if he is not afforded the opportunity, i.e., the full contract term, to recoup his investment…. To recover these expenditures they must have been reasonably made in the performance of the contract or in necessary preparation.

The Restatement (Second) of Contracts 349 (1981) states:

As an alternative to the [expectation damages], the injured party has a right to damages based on his reliance interest, including expenditures made in preparation for performance or in performance, less any loss that the party in breach can prove with reasonable certainty the injured party would have suffered had the contract been performed.

Further, in restatement (Second) of Contracts 349 comment a (1981), the author of the Restatement state:

Under the rule stated in this Section, the injured party may, if he chooses, ignore the element of profit andrecover as damages his expenditures in reliance. He may choose to do this…in the case of a losing contract, one under which he would have had a loss rather than a profit. In that case, however,it is open to the party in breach to provethe amount of the loss, to the extent that he cannot do so with reasonable certainty under the standard stated in 352, and have it subtracted from the injured party’s damages. (Emphasis added.)

Under these rules, Locke was entitled to the expenditures she incurred in order to perform her contract. Her uncontradicted testimony and exhibits prove the amounts of these damages.

Mistletoe’s argument that Locke must show what her position would have been at the earliest time the contract could legally have been terminated is misplaced. Under the cited rules, she can recover her reliance expenditures because she was deprived of an opportunity to recoup these expenditures. Moreover, Mistletoe is not entitled to have Locke’s losses deducted from the recovery, because Mistletoe have the burden to prove that amount, if any, and it did not do so. Restatement (Second) of Contracts 349 comment a (1981).

There is no evidence, however, to support an award of $19,400.00. That figure includes both the loss from the resale of the vehicles which were purchased with the loan and the current balance of the loan. Locke’s reliance damages were the amount of the loan ($15,000.00), less the amount recovered from the sale of the property purchased with the loan ($6,000.00).The resulting $9,000.00 should be added to the cost of the dirt work($1,000.00) and the loss from the materials for the ramp ($3,000.00). Furthermore Locke would be receiving a double recovery also if she recovers the full amount of the interest paid on the loan as well as the prejudgment interest allowed by the judgment.

For the reasons stated, the judgment of the trial court is reformed to award Locke the amount of $13,000.00, plus prejudgment interest thereon for 901 days, plus attorney’s fees of $2,000.00, as awarded in the original judgment. As reformed, the judgment of the trial court is affirmed.

About the author

Yicun Jiang (yicunjiang@ln.hk) obtained his PhD in English from Lingnan University,Hong Kong. His research interests include semiotics, metaphor study, and the philosophy of language. He is now lecturing and researching at the College of Foreign Studies,Shandong Technology and Business University, China.

Language and Semiotic Studies2017年4期

Language and Semiotic Studies2017年4期

- Language and Semiotic Studies的其它文章

- Developing Mathematics Games in Anaang

- Towards a Semantic Explanation for the(Un)acceptability of (Apparent) Recursive Complex Noun Phrases and Corresponding Topical Structures

- Complementiser and Complement Clause Preference for Verb-Heads in the Written English of Nigerian Undergraduates

- An Embodied View of Physical Signs in News Cartoons

- Grammar, Multimodality and the Noun

- Remapping, Subversion, and Witnessing:On the Postmodernist Parody and Discourse Deconstruction in Marina Warner’s Indigo