门

——随感一篇Doorway: A そought Piece

西蒙·昂温/Simon Unwin

徐知兰 译/Translated by XU Zhilan

门

——随感一篇Doorway: A そought Piece

西蒙·昂温/Simon Unwin

徐知兰 译/Translated by XU Zhilan

门一直都是建筑普遍语言中的重要因素。20世纪时,建筑师们为了从功能出发组织建筑空间和创造空间的美学体验探索新的方式,刻意地削弱了门的影响力。其后果却是现在门作为建筑要素的丰富潜质被极大地低估。本文提示了门的要素如何成为我们生活的句读,如何约束我们的行为,又感染我们的情绪。文章主张建筑师应更强烈地意识到门有助于他们通过不动声色、且丰富多彩的方式完成建筑构思。

The doorway has been a powerful element in the universal language of architecture throughout history.In the twentieth century architects reduced its power intentionally to open fresh ways of organising architectural space functionally and experiencing it aesthetically. But the consequence has been that the multifarious architectural potential of the doorway is now largely overlooked. This article is a reminder of the ways in which doorways punctuate our lives, influence our behaviour and elicit emotional responses. It argues that architects should be more aware of the subtle and diverse contributions the doorway can make to their repertoire of architectural ideas.

门,门槛,现象学,建筑的影响力

doorway, threshold, phenomenology, powers of architecture

在21世纪的今天,建筑的设计主要在计算机屏幕上完成,人们则主要通过互联网上的照片欣赏建筑。所以,我们有必要提醒自己,现实中的建筑才最具感染力——也就是我们在现实世界中直接体验建筑的时候——在建筑物塑造我们的行为、影响我们的表现、感染我们的情绪时。任何以照片或屏幕影像(即视觉形象)来展示建筑的方式,都无法让人尽情欣赏,因为建筑不只是视觉的媒介。建筑具有多重维度,远甚于三维空间与时间维度之和(尽管这些因素确实是建筑所依托的时空结构)。而我们作为人类个体和公众集体,也不只是建筑的旁观者,更是积极的参与者。建筑引导我们,鼓舞我们,确保我们安全,也感染我们的情绪,更为我们提供似乎无穷无尽的富于诗意的隐喻……最重要的是,建筑让我们的世界变得有理可循,并以润物无声却强而有力的方式作为空间组织的载体做到这一切。建筑本身就是普遍语言,与那些由单词和数字组成的语言迥然不同,尽管后者得到人们更为广泛的认可。

门是建筑普遍语言中一项强有力的元素。它如此不同凡响,以至于常被其他表现体裁引用(作为比喻)——从诗歌到喜剧,从商业广告到政治和宗教领袖向全世界表现自我的方式,从儿童故事到电影和计算机游戏等。多少次,侦探或超级英雄在小说里打破一道门、闯入其中对抗和摧毁邪恶势力;多少次,鸳鸯眷侣在一道门廊内外邂逅,四目相对,两情相悦;你又需要通过多少道门关,才能在错综复杂的网络世界中达到最高层级。等你下次再遭遇任何上述场景时,请思考一下这些叙事方式以何种方式借用门的要素。门是建筑语言不可或缺的一部分——这是一门比口头语言或数字语汇更古老的语言。动物既已懂得建造门的要素。我们可以在自然界辨认出门的要素——洞口、树间的空隙、山脉间的孔道……自从最遥远的史前时期伊始,门就已成为人类建筑的重要元素。作为建筑师,我们应当提醒自己认识其潜质,并懂得如何巧妙地加以利用,以增强作品的震撼力和诗意。

在本文中,我只能用平面图像来说明门的案例,但我希望你能以四维的空间体验方式来解读我的案例——即将其理解为在一处处空间之间、耗费一些时间完成转换的过程。门的力量不仅在于其外观,更在于它们所代表的种种机会或威胁,在于人们在走近和穿越门廊的过程中发生转变的体验。如果你休息片刻,暂停阅读,请闭上眼睛,仅仅想象自己正走近一道门,你就会感受到有所期待;如果你更进一步踏进门槛,在穿过敞开的门廊去探索另一侧的“新世界”究竟如何的时候,你还会经历到一阵兴奋。(以作为建筑师所拥有的想象力,你不妨自行决定那个“新世界”的样貌。)

门是我们生活的句读。我们在家中走动或是穿行于城市中时,从一间屋子到另一间屋子、从一处地点到另一处地点之间,我们不假思索地跨过一道道门槛。每越过一道门槛,我们就有所变化,有时悄无声息,有时又引人注目。让我们从你自己的生活中想象一些例子。譬如你离开家门,从私人空间进入公共领域——你的情绪状态、外在形象变化了——好像演员进入舞台去面对观众。你在等待一场面试,随后被要求走进房间去面对面试官的提问,在你迈进那道门的刹那,你的精神状态变化了——你将处于他人的严格审视之下。在一道门廊的后面,你见到了男友或女友,你绽开了笑容。你怒气冲冲地摔门而去,以此凸显你的愤怒。在比赛前或演出开场前,你走进体育馆或剧院的大门;你焦躁地等待,翘首以盼;之后哨声响起,或是帷幕拉开,比赛或演出终于开始。夜幕降临,你回到家,走进卧室后关上房门,心跳减缓,你放松下来。门,即使它关闭或开敞的门扇,是你在这世上日常生活中生机勃勃的要素。

门具有无穷无尽的隐喻潜质。我们常提到身体之“门窍”——人体的每一个孔窍功能各异,世界上有一些部落民族把它们阐释为房屋建造门窗的方式。死亡则被诗化为“穿越死亡之门”——经由联想,墓室的入口似乎也获得了特殊意义。在出生时,我们经过孔道,由子宫的保护进入光亮刺目的世界。由人生的一个阶段进入下一阶段的节点则被称为“开端”或“门槛”,并经常以包含有从现实的通道踏进门槛或通过门廊环节的仪式来表明这些时刻。婚礼之后,两个人并肩走出一道大门,作为缔结了婚姻关系的伴侣共同去面对这个世界。毕业典礼之后,莘莘学子作为毕业生走出校门,踏上社会。全世界和道路有关的仪式都包含通过大门或门廊的环节。每经过一道门,我们就会以微不可察的方式、或偶尔以恢弘伟大的方式得到重生。在这些情景下,建筑的普遍语言在现实的建筑中得到了表达,并与我们的自身生命产生了密切的关联。与门相关的隐喻还有很多。我们会提到“关起门来”做秘密决定。我们“打开大门”来欢迎朋友,或欢迎新鲜的体验来丰富我们的生命。这些诗意盎然的隐喻影响了我们在现实中如何使用建筑的门。它们也影响了我们如何设计建筑的门。

门能形成轴线。自古以来,门就是定义轴线的工具。英国古代墓葬的门通过对位的方式与冬至日太阳的位置取得联系。雅典卫城的入口将圣殿与萨拉米斯岛附近意义重大的海战战场相联系。教堂与庙宇的入口引导走近它们的崇拜者靠近上帝或来到圣坛。回顾历史,门一直都象征着权威。宗教利用门引发人们对超越性界域的思考,并且用门形成指向世俗世界的轴线作为权威的象征。他们利用门定义神圣空间——即让我们可在其中得到神明保护、远离尘嚣的避难之所。我们可以悄然溜进这些门内,以逃避世俗的囚禁,抑或寻求庇护。军队会攻击大门。军事防御工事会对门的位置进行保护,因为它们是相对薄弱的环节。政治家居住在门后责任重重的世界,然后走出大门发表公开演讲——相机记录下这些演讲,画面上的门赫然在目,象征政治家的责任范畴;演讲结束后,他们又经同一道门返回,去面对各种挑战。我们观看这些事件的屏幕也是一道把我们和他们联系起来的“门”。

In these twenty- fi rst century days, when buildings are primarily generated on computer screens and admired through photographs on the Internet, it is worth reminding ourselves that architecture is at its most powerful in its actuality – when our experience of buildings is direct, in the real world; when buildings frame our activities, influence our behaviour, affect us emotionally. Any depiction of architecture as an image in a photograph or on a screen (i.e. as a twodimensional image) never provides a full appreciation of it because architecture is not merely a visual medium. Architecture has many dimensions; many more than the three spatial dimensions plus time(though these do provide the fundamental space-time framework within which architecture operates). We, as individuals and as the general mass of human beings,are not merely architecture's spectators, we are active ingredients. Architecture guides us, informs us, keeps us safe, surprises us, affects our emotions, provides us with seemingly in fi nite poetic metaphors… Above all,architecture makes sense of the world for us. It does so in the tacit, but nevertheless powerful, medium of spatial organisation. Architecture is a universal language in its own right, distinct from the more commonly acknowledged languages of words and numbers.

1 建筑可以摒弃门的要素。20世纪一些建筑师的此类尝试极大丰富了建筑的普遍语言——他们让空间和场所在彼此间顺畅地流动——因没有门而让人感到毫不停歇、毫无断层、毫不犹豫。然而,如果我们忽略了门的作用,建筑的语言是否会被削弱?/Architecture can be made without doorways.Attempts by some twentieth-century architects to create such buildings have enriched the universal language of architecture;they allow spaces and places to fl ow seamlessly from one to another without punctuation, without the fault-lines and hesitations that doorways provoke. But is the language of architecture diminished if we neglect the power of doorways?

The doorway is a potent element in the universal language of architecture. Its potency is so great that its power is often enlisted as a device (a trope) in many other media of expression: from poetry to plays;from commercial advertising to the ways political and religious leaders present themselves to the world; from children's stories to movies and computer games. How many times has a fi ctional detective or super hero burst through a doorway to confront and destroy a malign threat. How many times have lovers met, face to face,eyes locked, through a doorway. How many doorways do you have to pass through to reach the highest level of a labyrinthine cyber world. The next time you encounter any of these, think about how those narratives use the doorway. The doorway is an essential part of the language of architecture – a language that is older than the language of speech or of mathematics.Animals make doorways. We recognise doorways in the natural world – the mouths of caves, a gap between two trees, a pass through the mountains… Doorways have been signi fi cant elements of human architecture since the most distant prehistoric times. As architects we should remind ourselves of their potential and how we might use it consciously and with deliberation to enhance the practical and poetic power of our work.

2 门为建筑带来诗意。它们能同时在实践层面和实验性方面表现出诗意。在性格迥然不同的场所之间,门分隔了空间,也形成过渡。它们能引起期待和渴望,也能暗示“另一个世界”的存在,并提供向其中窥视的视野,引人入胜,并带来了从一个世界逃往另一个世界的可能性。/Doorways contribute to the poetry of architecture. They have great practical and experiential poetic potential. They divide but also create transitions between places that can be of dramatically different character. They can elicit emotions of anticipation and aspiration. They can suggest, and provide tantalising views into,"other worlds". They can offer the possibility of escape from one world into another.

In this paper, I can illustrate examples of doorways only with two-dimensional images, but I would like the audience to interpret my examples as four-dimensional experiences: transitions from one place to another,a spatial process that also takes time. The power of doorways lies more than in how they look; it lies in the opportunities or threats they present and the transformative experience of approaching and passing through them. If you were to stop reading these words for a moment, close your eyes, and do no more than imagine approaching a doorway you would feel a sense of anticipation; if you step further you will experience a thrill as you pass through the doorway's opening to see the "new world" that is on the other side. (With your architect's imagination, the nature of that "new world"is up to you.)

Doorways punctuate our lives. As we move around our homes or our cities we pass through doorways without thinking as we move from room to room, place to place. And each time we pass through a doorway we ourselves are changed, sometimes imperceptibly,sometimes dramatically. Imagine examples from your own life. When you leave home, you pass from your private world into the public realm – your emotional state, your persona, changes… like an actor emerging onto a stage in front of the audience. When you wait for an interview and are then asked into the room to face those who will question you, as you pass through the doorway your state of mind changes… you come under scrutiny. When you meet your boy- or girlfriend in a doorway, you smile. When you storm out of a room you slam the door behind you, to emphasise your anger.When you enter a sports arena or a theatre before the game or performance, as you pass through the entrancethe field or stage is spread out before you; you wait with impatient anticipation; then the whistle blows or the curtain lifts and the show begins. At night, when you return through your bedroom doorway and close the door, your heart beat slows and you are relaxed.Doorways, and the doors by which they are closed and opened, are active instruments in our daily experience of the world.

20世纪时,曾有建筑师力图摒弃门的要素,或至少要将其固有的影响力降至最低甚至消除殆尽。一些建筑师把门和它的主导轴线与(宗教、皇室和政治的)特权阶层文化相关联,认为是它们导致了第一次世界大战的灾难和其他社会剧变。他们着手建造在现实空间和隐喻意义上都能够没有门的建筑。在勒·柯布西耶1920年代发表的文章和密斯·凡·德·罗的作品中,我们都能看到对“开放”或“自由”平面的主张——空间在房间与房间之间自由流动——这些平面都没有门的布置;以及建筑周围空间自由流动的城市——亦即没有等级分明、象征特权的轴线。这一隐喻意味深长。它深刻地改变了人们设计建筑的方式。避免使用门及其相关轴线的渴望既成了审美的需求,也成为隐喻的主题。

3门可以分隔对立的事物——耀眼的阳光与黑暗的阴影;宜人的温暖与刺骨的寒冷;喧嚣与静谧;匮乏与特权;威胁与安全;隐秘独处与公开亮相……同时,它也建立了两者之间的关联。门在我们身上制造万有引力,将我们拉近它,邀请我们通过……也许,有时它们也充满诱惑和欺骗。/A doorway can divide opposites: dark shade from bright sunlight; icy cold from balmy warmth; silence from noise;privilege from deprivation; threat from safety; private solitude from public exposure... but at the same time provide access between the two. Doorways can exert a gravitational pull on us, drawing us towards them, inviting us to pass through...maybe sometimes they seduce to deceive.

建筑发生了翻天覆地的变化。建筑材料和结构体系的科技进步也助长了这一趋势。开放的平面更容易通过钢和混凝土框架实现。墙体更为轻巧,并可独立于结构存在。平板玻璃也可被当作完全通透的墙体。“开敞”的理念由此得到进一步加强。如今,我们在当代建筑设计作品中能见到许多以玻璃幕墙乔装成门的尝试,配以设计精巧的细部——铰链、门把手、扶手等——这些门与玻璃墙面俨然一体,几乎不可分辨。而所有这些努力都只为一并减弱甚至彻底消解室内与室外的边界、及其比喻的内涵和美学特征。门似乎已是禁忌。

但是,在建筑中尽可能消除门的努力恰如从书面语言中尽可能取消标点符号一样。它们都是各自语言体系中必不可少的要素。记得在詹姆斯·乔伊斯的《尤利西斯》(1922年)中就有一部分文字没有句读,让人疲于阅读也难以理解。尽管这种做法在当时引起了轰动,这一实验却后继乏人。门的表达形式和体验方式有多种可能,其重要性远甚于句号和逗号的用法。20世纪时对门的厌恶意味着建筑师已经对如何加强人们体验建筑、与建筑互动的方式失去了探究的兴趣。

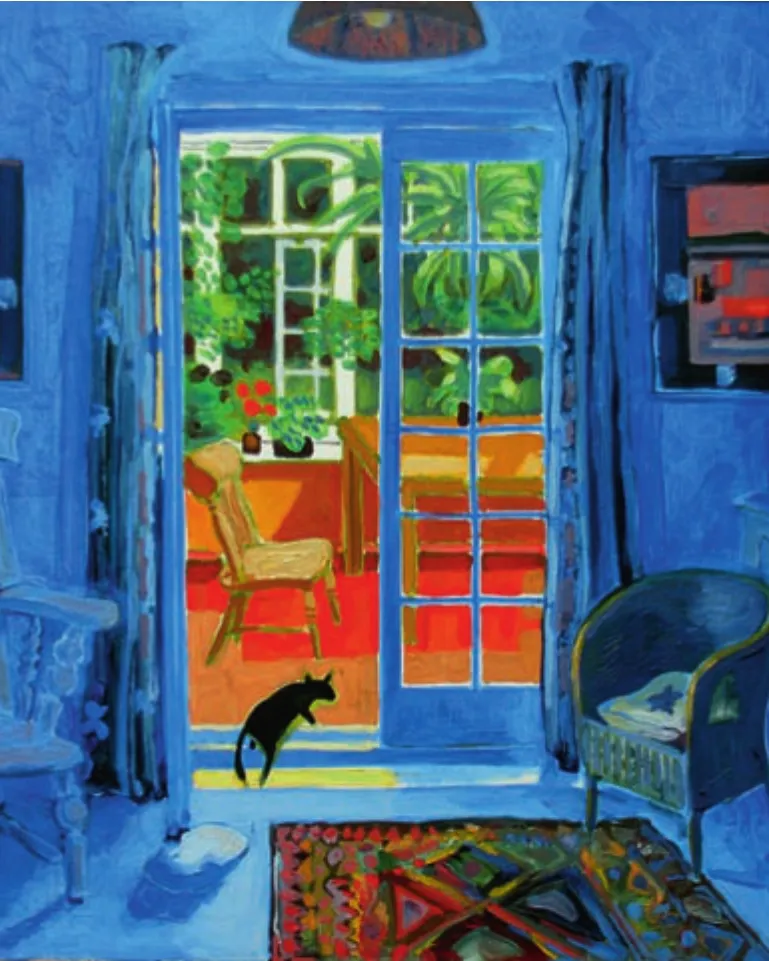

4门能把我们带离凉爽的起居室,进入充满植物与花卉的温室。由此,门为我们提供了多姿多彩的建筑体验。它们把我们在建筑中穿行的过程交织成一曲交响乐,让我们沉浸在犹如受到音乐感染的情绪中。一道门槛也是变化发生的一瞬间。随着我们所处地点的个性发生变化,我们也随之改变。/A doorway can take us from the coolness of a living room into the warmth of a conservatory full of greenery and fl owers. In doing so doorways enable dramatic variety in our experience of a building. They orchestrate our movements through a building, affecting our moods like in music. A threshold is a moment of transformation. As the character of the place in which we fi nd ourselves changes, we do too.

门的建筑学潜质较其实际用途广泛得多。门是可以独自存在的地点。古代的法律诉讼往往在城市的入口处举行,可能是因为异端份子一经定罪,就会被人关进城市的防御塔或驱逐出境;也可能因为门具有门槛的本质,因此在比喻的意义上,似乎与这一场景的特质不谋而合——它既是判断无辜与犯罪、自由与监禁的交点,也是城市内部社群的公共法律与不受法律控制的城市外部世界之间的界限。在温暖的气候条件下,人们会惬意地坐在屋舍门口,它既属于公共领域,也是他们的家庭空间。店老板坐在商店门口欢迎潜在的顾客。庙宇自古以来都有高敞宏伟的大门作为从外部凡尘俗世进入内部神圣世界之间的过渡空间;它是供来访者毕恭毕敬地鞠躬或脱鞋的地方,或是葬礼开始前可以停灵片刻的地点。如今的游客景点也有入口建筑,可出售门票和导览手册,或供游客购买纪念品;它们也同样具有在平淡无奇的外部世界和游客特别赶来观看的“另一个世界”之间进行过渡的作用。

5门可以形成景框,成为房间里并非一成不变的“图片”,随着冬去春来、日升月落而变化。门(和窗)通过框景,让我们能远近借景(也许并不“属于”我们)。门也提供了一处“中间状态”的地点,让我们既不在室内也不在室外,却又同时属于并占有二者。/Doorways can frame views, providing rooms with "pictures" that are not fi xed and change with the times of day and the seasons of the year.Doorways (and windows) enable us to borrow scenery from near and far (and which may not "belong" to us) by drawing it into our rooms. Doorways also offer a place "in-between",where we are neither inside nor outside, but possessed by and possessing both.

6门是公共领域与我们自宅私人空间之间的界限。是我们欢迎来宾之处。是我们定义自身身份之处。是我们接受信函之处。通常门不会截然割裂空间,而是属于一系列从“公共空间”到“半公共空间”、到“半私密空间”、直到“私密空间”的序列。它也能让视线透过……譬如它在这里能让人看见附近的海面。/A doorway is the interface between the public realm and the private worlds of our own houses. It is where we welcome visitors. It is where we identify ourselves. It is where we receive missives from elsewhere.Often the doorway does not mark a clear divide, but is part of a sequence that passes from "public", to "semi-public", to "semiprivate", to "private". It can also provide a view through... in this example to the horizon of the sea in the distance.

The doorway has endless metaphorical potential.We speak of the "doorways" of the body; each opening has a different purpose, which some tribal peoples of the world translate into the ways they build openings in their houses. Death is depicted poetically as "passing through a doorway"; by association, the doorways of tombs seem to acquire particular signi fi cance. At birth we pass through a doorway from the security of the womb into the bright world. Passage from one stage of life to the next is called a "threshold" or "doorway"; and can often be marked by ceremonies involving actual passage over a threshold or through a doorway. After a marriage ceremony, two people emerge from a doorway to face the world as a married couple. After degree ceremonies, students return to the world through a doorway as graduates. Rites of passage around the world involve passing through gates or doorways. Every time we pass through a doorway we are reborn in a miniscule or, occasionally, in a grand way. In such instances the universal language of architecture, expressed in real buildings, is intimately engaged with our lives. There are many metaphors associated with the doorway. We speak of secret decisions being made "behind closed doors". We"open our doors" to friends to welcome them, or to new experiences as a way of enriching our lives. Such poetic metaphors influence how we use the real doorways of buildings. They should influence how we design the doorways of real buildings too.

7就像剧院的舞台台口拱门,门能形成分隔的框架要素,分隔象征尊卑的空间。文艺复兴时期的一位王子可以躺在这张精致繁复的床上觐见一门之隔的朝觐者,后者只能被限定在另一个空间里。这道门增强了王子公认的优越感、及其对于他人而言遥不可及的社会地位。/Like the proscenium arch of a theatre, a doorway can frame the divide between the make-believe world of privilege and its inferior subjects. A Renaissance prince might hold court lying in a ceremonial bed framed by a doorway, whilst supplicants were con fi ned to a separate space. The doorway reinforces the prince's assumed superiority, and the inaccessibility of his social position to others.

A doorway generates an axis. Since ancient times doorways have been used as instruments of axial linkage. By alignment, the doorways of ancient burial chambers in Britain were linked to the sun setting on the winter solstice. The doorway into the Acropolis in Athens links the sacred sanctuary to the site of signi fi cant naval battle near the island of Salamis. The doorways of many churches and temples link the approaching worshipper to the god or altar within. Through history doorways have been used as instruments of authority. Religions use doorways to evoke the idea of a world beyond, and establish the authority of the axis that projects out into the world. They use doorways to define a sacred realm,a refuge from the world where we are safe in the protection of the gods. We slip through doorways to escape confinement, or perhaps to find refuge.Armies attack doorways. Fortresses protect their doorways because they are weak points. Politicians inhabit worlds of responsibility behind doorways,and emerge through them to make public statements;cameras film those statements with the doorway of their realm of responsibility visible behind; and after their statement they go back through that doorway to address their challenges. The screens on which we watch such events are "doorways" that link us to them.

8更多的普通人——尤其在温暖气候地区——喜欢坐在家门口招呼过往的邻居闲聊几句。坐在自家门前的树荫下读报、喝咖啡、和左邻右舍打招呼是最惬意的打发时间的方式之一;它让人能有机会进行哲学沉思,也能让你能回到室内去接电话。/More ordinary people, especially in warm climates, enjoy sitting by their doorways so they can greet and chat with passing neighbours. Sitting by one's doorway,under the shade of a tree, reading the paper, drinking a coffee,greeting neighbours, is one of the most enjoyable ways to spend time. It offers the possibility of a time for philosophical musing. It also means you can run back inside to answer the telephone.

门既分隔了不同的世界,也联系了它们。剧院舞台口的拱门——和电影院、电视机或计算机的方形屏幕一样——实际上是不同世界之间的大门,是我们过着平凡生活的普通世界和我们在其中享受并向它投射想象的另一个世界之间的大门。现实的建筑物也有异曲同工的作用。回想一下凉爽荫蔽的起居室和温暖明亮、充满绿植和缤纷花卉的温室之间的关系。介于两者之间的门形成了从一处空间望向另一处空间的景框——在荫蔽的一侧瞥见明亮鲜艳的一侧;从温暖的一侧窥视凉爽的一侧。在一些文艺复兴时期的宫殿里有国王卧室,它由两间单独的房间所组成,之间用仿佛剧院台口拱门般高大的“门廊”隔开。其中一间布置有一张以名贵的纺织品点缀的豪华睡床,各种精巧的物件则环绕在周围,贵族成员或皇室成员在此接见能被允许进入隔壁房间的拜访者,隔壁这间被拱门隔开的房间则仿佛是一个不同的世界。同理,庙宇的入口或教堂的圣坛拱券也分隔了神圣空间和我们凡俗的世界。进入一座墓葬的过程也与神话英雄进入死后的世界与亡者对话相类似。

9门是我们等待朋友和会面的地方。富于诗意的是,门能同时象征一对伴侣的团聚和分离。在许多叙事体裁中——文学、电影、戏剧……——门都不言而喻地被用作发生聚散离合、惊讶、欣慰、愤怒、孤立等情节的地点。对门的叙事功能运用通常是下意识的——也就是说 ,在我们的意识之门背后。/Doorways are where we wait for and meet our friends. Poetically a doorway manages to symbolise both the unity and the separation of a couple. In many forms of narrative – literature, movies, drama... – the doorway is used as a tacit device for framing reunion, separation, surprise,relief, anger, isolation... The narrative power of the doorway often works subliminally – i.e. beneath the threshold of our consciousness.

门的功能多种多样。门是我们表达个性与身份的地方——不仅通过铭牌和标志,也经由门本身的特点进行表达。肮脏破败、陈旧不堪的门让我们对住在门后的人有所了解。雄伟高大、超凡出众的镀金大门则告诉人们,它的主人想让别人相信自己也同样超凡出众、熠熠生辉、引人注目。谦和朴素的门则暗示着它通往纯粹简单的生活。门当然也可能说谎。

一道门也可以是一道滤网抑或阀门。门把可能进入或离开一处场所的人和那些固定不动的人区分开——人们必须在门口出示名片或邀请函,或购买门票,或花费一番说服的口舌。门区隔危险的地点和安全的地点——宇宙飞船或核反应堆都有设计精巧的“气闸室”作为出入口,防止氧气从宇宙飞船泄漏或核泄漏。会议室和医生诊室的门为人们讨论较为敏感的问题提供隐私的保护。门感染人们的情绪。在电影里,即使最自信的侦探也会在进入审讯罪犯的陌生法庭之前感到一丝不安。而就算是最紧张不安的逃亡者也会在终于找到的避难所上锁的门后感到一丝欣慰和放松。而电影结束则好像关上了一扇门。

10一般而言,门是入口,让我们能毫无困难地来往于不同的地点之间。但有时候,门也是我们的停歇之所,阻止我们去往远处。门是保安阻挡陌生人的地方,是“保镖”禁止衣着不整者进入的地方……宫殿“禁地”就在这一道道门的背后,它们因其禁止入内的性质,显得更有威严。/Generally doorways are ports of entrance, they allow us to pass between separated places without diきculty.But sometimes doorways are where we are stopped ;prevented from going further. Doorways are where guards halt strangers, where "bouncers" forbid entry to those not dressed appropriately... The "forbidden" places behind such doorways, become more tanalising because access is barred.

综上所述,作为建筑通用语言的组成要素,门充满潜质。如果我们视而不见门具有的可能性,就会让建筑学变得贫瘠。门的作用可以是激动人心,也可以是细致入微、诗意盎然的。使用门的方法则无穷无尽。

通常,我们经过一道道门而熟视无睹;我们的注意力不是在向往门另一侧的世界,就是在思索如何从我们正远离的空间逃遁。但是作为建筑师,我们应当意识到门具有许多可能性,我们肩负对它们进行设计的责任。我们经常考虑门的外观和建造方式,对其功能和如何更好地实现这些功能,以及它对进入建筑的空间体验还能提供什么则缺乏足够认真的考量。

我们可以利用门实现许多目的——譬如让我们的建筑使用起来更实用、宜居和激动人心。我们可以有意识地利用门,为人们进入建筑、在其附近活动和离开建筑编织一曲空间体验的交响。我们可以用门的物质形式形成隐喻。我们如何运用门的要素来做设计会影响许多人认识世界的方式。□

11墓室的门好像通往死亡自身之门。墓室作为凄苦不堪、死气沉沉之处,其入口通常沿着狭窄逼仄的甬道展开。门是从濒死的压抑向死亡本身的凄凉过渡的瞬间。也许这世间再也没有更震撼人心的隐喻了。墓室也是最古老的建筑类型之一,可以回溯至史前时代。/The doorway of a tomb is like a doorway into death itself.Tombs are desolate, drab places, and their entrances are often approached along narrow, oppressive passageways. The doorway is the moment of transition from the oppression of dying into the desolation of death itself. There is perhaps no metaphor more powerful. And it is one of the oldest in all architecture, stretching way back into prehistory.

In the twentieth century some architects tried to abolish the doorway, or at least minimise or counteract its intrinsic power. Some associated the doorway and its dominating axis with the cultures of privileged authority (religious, royal and political) that had contributed to the disaster of the First World War and other social upheavals. They set about creating an architecture that would create a world without doorways, physically and metaphorically. In the 1920s writings of Le Corbusier and the work of Mies van der Rohe we see arguments for the "open" or "free" plan:plans in which rooms flow freely one into the next –plans without doorways; cities in which space flows freely around buildings – cities without the hierarchical axes of authority. This metaphor is powerful. And its effect profoundly changed the ways in which buildings were designed. The desire to avoid the use of doorways and their related axes became an aesthetic as well as a metaphorical issue.

Architecture changed fundamentally. And the advancing technology of building materials and structural systems helped that change. Open plans were made easier by steel and concrete frames. Walls could be lighter and independent of structures. Plate glass made it possible to create walls that were completely transparent. In these ways the idea of "openness" could be reinforced further. Nowadays, in contemporary work, we see attempts to camou fl age doorways in glass walls, with details – hinges, catches, handles – carefully designed so the doorways are almost indistinguishable from the general glazing. All this is done so that the barrier between outside and inside, with all its metaphorical connotations as well as aesthetic characteristics, might be reduced or even eliminated. It is as if the doorway is a forbidden concept.

But trying to abolish the doorway from architecture is like trying to abolish punctuation from written language.Both are essential elements of their respective languages.Remember that part of James Joyce'sUlysees(1922) is written without punctuation, making it tiring to read and difficult to understand; though sensational at the time, it is not an experiment that has been much repeated. The expressive and experiential possibilities of doorways are far greater than those of full stops and colons. The twentieth-century aversion to doorways means that architects have lost interest in the ways they could be used to enhance how people experience and interact with buildings.

12尽管20世纪曾有一些建筑师试图将门从建筑的语汇中消除掉,另一些建筑师则继续探索其表达诗意的潜质。这是格尔德·卢弗伦斯在斯德哥尔摩斯林地公墓设计的复活堂(1925年),铜制十字架既是基督教的象征,也是表示不得从此门进入教堂的符号。然其阴郁的气质也让它变成了一道“死亡之门”。/Though some twentieth-century architects sought to banish the doorway from the language of architecture, a few continued to relish its poetic potential.Here is the exit doorway of Sigurd Lewerentz's Chapel of the Resurrection (1925) in Stockholm's Woodland Crematorium.The cross of its bronze panels is both a Christian symbol and a sign that indicates that you are not supposed to enter the chapel by this door. But its sombre character also makes it a"doorway of death".

13卢弗伦斯在他于瑞士克利潘的圣彼得教堂(1966年)里,设计了各式各样的门。他甚至让人从外部公共空间很难找到进入教堂的方式。入口处的门廊谦卑谨慎而隐蔽不见。等你终于找到了它,它又将你引入一个充满神秘的洞穴般的室内空间。这张照片上只有一个简单的入口,让游客从幽暗的入口礼拜堂进入光线明亮的主教堂。/In his Church of St Peter at Klippan in Sweden (1966), Lewerentz used doorways in many different ways. He even made it difficult to find the way into the church from the public world outside. The entrance doorway is humble and hidden away. When you eventually fi nd it, it transports you into a mysteriously cave-like interior world. In this photograph a simple opening entices the visitor through from the shady entrance chapel into the starkly-lit main church.

14瑞士建筑师彼得·卒姆托也同样对门如何影响我们进入建筑的体验做过一番探究。这是他在库尔的罗马考古遗址保护棚(1986年)的入口。门由悬挑的金属方盒作为边框,并在其中包含几级台阶,我们的体验也得到拓展。当我们步入其中,入口的方盒会在我们的体重影响下稍有颤动,让我们感受到自己正在进入一处陌生的世界——历史的空间。/The Swiss architect Peter Zumthor has also been interested in the powers doorways have to affect our experience of entering a building. そis is his entrance to the Roman Archaeological Shelter at Chur (1986). The doorway is framed, and our experience of it extended, by a cantilevered metal box that also incorporates steps. As we step onto it, the box moves slightly under our weight, giving us the feeling that we are entering a foreign world – the world of the past.(1-14摄影/Photos: 西蒙·昂温/Simon Unwin)

The architectural potential of the doorway is much broader than its practical usefulness. Doorways are places in their own right. In ancient times legal proceedings were held at the gateways of cities, presumably so miscreants, if found guilty, might be locked in one of the defensive towers or banished from the community;but probably also because the threshold nature of the gateway seemed in some sort of metaphorical harmony with the threshold nature of the occasion – i.e. the cusp of innocence or guilt, freedom and imprisonment, the line between the communal laws of the city and the lawless world outside. In warm climates, people enjoy sitting at the doorways of their houses so that they can be part of the public realm as well as of their own homes.Shopkeepers sit by the doorways of their stores to greet possible customers. Temple grounds since ancient times have been given grand gateways as transitions from the secular world outside to the sacred world within;where visitors bow or remove their shoes in respect, or where coきns rest for a moment before funeral services.Nowadays tourist sites have entrance buildings where tickets and guidebooks are sold and souvenirs bought;they too have the effect of creating a transition between the ordinary world outside and the special "other world"tourists have come to see.

Doorways separate as well as link different worlds.The proscenium arch of a theatre – like the rectangular screen of a cinema, television or computer – is effectively a doorway between one world and another,between the world in which we live our ordinary lives and another into which we enjoy projecting our imaginations. The architecture of real buildings can do this too. そink of the relationship between a cool shady living room and a warm and bright conservatory fi lled with green plants and colourful fl owers. Between the two, the doorway frames the view from one into the other – from the shade into the light and colour; from the warm into the cool. In some Renaissance palaces there are state bedrooms consisting of two chambers separated by a large "doorway" like a proscenium arch; in one of these chambers would be a grand bed,bedecked with expensive fabrics and surrounded by fi ne objects, from which the noble or royal personage would receive visitors allowed into the adjacent chamber, separated as it were in a different world by the proscenium doorway. Likewise, the doorway of a temple or the sanctuary arch of a church distinguishes the world of the god from that of us mortals. And entering a tomb can be like a mythical hero entering the afterworld to speak with the dead.

Doorways do many things. Doorways are where we express our identities; not only with name plates and logos but by the character of the doorway too. A dirty,worn, decrepit doorways says something about who lives behind it. A grand, larger-than-life, gold-plated doorway says that the person to whom it belongs wants others to believe that he too is larger than life and,metaphorically, plated in gold. A modest neat doorway suggests it leads into the home of a pure simple life.Doorways may of course tell lies too.

A doorway can be a filter or a valve. Doorways are where those who may enter or leave a place are separated from those who may not; they are where identity cards or invitations must be shown, tickets bought or persuasion attempted. Doorways separate dangerous places from safe ones; space ships and nuclear reactors have elaborate "air-lock" entrances that prevent air being lost from a space ship and radiation escaping from a reactor. The doorways of meeting rooms and doctors' consulting rooms provide privacy for sensitive discussions. Doorways elicit emotional responses. In movies, even the most con fi dent detective feels a hint of trepidation entering a strange bar frequented by criminals. And even the most nervous of fugitives breathes a sigh of relief and relaxation when they fi nd refuge behind a locked door. And the movie ends with the closing of a door.

To conclude… as an element in the universal language of architecture, the doorway is rich with potential. By neglecting the possibilities the doorway offers we make architecture poorer. The powers of the doorway can be both dramatic and subtly poetic. There are in fi nite ways in which they may be exploited.

In general, we pass through doorways without noticing; we are intent on projecting ourselves forward to the other side, or on escaping the place we are leaving. But, as architects, we should be conscious of the range of capabilities doorways offer. We are responsible for designing them. We consider what doorways look like and how they should be constructed. But often we do not think hard enough about what a doorway is doing, how it might do it better, and what else it could do to enhance the experience it offers.

We can do things with doorways; do things that will make our buildings more practical, enjoyable and stimulating to use. We can use doorways consciously,to orchestrate the experiences of those who will enter,move around, and exit our buildings. We can make metaphors in physical form. Our use of doorways can in fl uence how people see the world.□

/Biography: 任教于卡迪夫大学威尔士建筑学院。邓迪大学名誉教授。已出版中文版书籍《解析建筑》(中国水利水电出版社,2002)、《门》(电子工业出版社,2014)/Simon Unwin is Emeritus Professor of Architecture at the University of Dundee in Scotland. He studied architecture at the Welsh School of Architecture in Cardiff, where he continues to teach. His books include Doorway (Routledge, 2007) and Analysing Architecture (4th edition, Routledge, 2014), both of which are available in Chinese.

/Received Date: 2017-11-10

- 世界建筑的其它文章

- 传统文化与地景建筑的结合

——上海顾村规划展示馆设计TheCombination of Traditional Culture and Landscape Architecture: The Design of Shanghai Gucun Planning Exhibition Hall - 改进建筑60秒Sixty Second Idea to Improve Architecture

- 古建新衣

——欧洲城市如何通过创新性建筑系统翻新实现改变New Skin – Old Building: How European Cities are Changing そrough Innovative Retro fi t Building Systems - 地下空间的开放与流动:海牙地下电车隧道案例解析Open and Flowing Underground Space: Case Study of Hague Souterrain Tram Tunnel

- 定远营古民居建筑形制初探Discussion on the Architectural Form of Ancient Dwellings in Dingyuanying

- 成都来福士,成都,中国CapitaLand Raのes City Chengdu, Chengdu, China, 2012