乳腺癌多基因面板测序的成本效果分析

杜春艳

澳门大学中华医药研究院 澳门 999078

·卫生技术评估·

乳腺癌多基因面板测序的成本效果分析

杜春艳

澳门大学中华医药研究院 澳门 999078

目的:以英国德系犹太妇女人群为背景,用决策模型评估多基因面板检测在乳腺癌与卵巢癌筛检上的成本效果。方法:结合英国人口流行病及成本数据,建立决策树模型,基于付费者的角度,从多个文献中获取相关概率和成本数据,进行成本效果分析。成本以2014年价格为基准,采用3.5%的贴现率进行贴现。通过单因素敏感性分析和概率敏感性分析测试模型的稳健性。结果:与无基因检测相比,多基因面板检测降低了1.1%的癌症发生率,挽救了601例乳腺癌和283例卵巢癌患者,延长了0.87个生命年和0.89个质量调整生命年,增量成本效果比为£6 766/QALY。敏感性分析显示模型稳健性较好,乳腺癌易感基因突变率是影响模型的重要因素。在£20 000/QALY~£30 000/QALY的阈值范围内多基因检测有90%以上的概率具有成本效果。结论:与无基因检测相比,乳腺癌二代面板测序在突变率较高的英国德系犹太妇女人群中具有成本效果。

乳腺癌; 成本效果分析; 决策模型; 二代多基因面板

乳腺癌是全球女性最常见的恶性肿瘤,死亡率居癌症死亡前列。[1]据国际癌症研究中心(International Agency for Research on Cancer,IARC)统计,2012年全球新增乳腺癌发病167万例,死亡19.8万例。预计到2025年全球将新增217万个乳腺癌病例,其中70万死亡病例。[2]

乳腺癌的发生是遗传因素和环境因素共同作用的结果。其中,5%~10% 是由高外显率的遗传基因突变引起的。[3]BRCA1和BRCA2是最常见的乳腺癌易感基因,BRCA1、BRCA2突变携带者70岁前患乳腺癌的累计风险高达80%,同时伴有40%的卵巢癌风险。[4]除此之外,还有若干基因被发现与乳腺癌的发病有关,包括TP53、CDH1、PALB2、STK11等,均会在一定程度上提高乳腺癌患病风险。对乳腺癌易感基因的遗传检测,有利于及早识别乳腺癌高危人群,及时进行风险管理,从而降低患病率,提高治愈率。二代测序的到来使得以较低成本进行大规模基因测序成为可能,而包含多个癌症基因位点的二代基因面板检测(Next-generation sequencing panel,NGS panel)也逐渐成为评估癌症遗传风险的新选择。

乳腺癌在普通人群中发病率较低,开展大规模人群基因检测成本相对较高。BRCA1、BRCA2基因检测是目前少数已有证据证明其效用并投入实践的遗传临床应用。现有研究表明,以人群为基础的BRCA1、BRCA2基因检测对于高风险的德系犹太人群具有成本效果,以家族史为基础的基因检测具有潜在成本效果,以癌症为基础的基因检测具有较可观的经济性,但对于一般人群进行基因检测仍然过于昂贵。[5]

随着大规模并行测序技术的发展,测序成本大幅度下降,多基因面板测序成为新的成本效果可能。一项比较多基因面板检测和单基因检测效果的研究发现,多基因面板比单基因检测的突变检出率高2.9%(6.7% VS. 3.8%),成本也相对提升了21%,具有成本效果。[6]两篇关于二代测序面板的经济学评价研究显示,多基因面板在大肠癌和息肉综合征诊断及转移性黑色素瘤患者治疗选择上具有可观的成本效果。[7-8]由此可见多基因面板在癌症遗传风险评估上的巨大潜力。乳腺癌的发病与多个基因有关,多基因检测能够识别更多具有临床意义的突变,为被单基因检测忽略的癌症风险基因携带者提供更综合的风险评估,使更多的人受益。现阶段市场上已经出现多个商用的乳腺癌多基因面板,但尚未发现与乳腺癌多基因面板测序有关的卫生经济评价研究。本研究旨在对乳腺癌多基因面板检测进行卫生经济学评价,比较其与无基因检测在高风险乳腺癌或卵巢癌人群的成本效果,为多基因面板检测的应用提供经济学参考。

1 资料与方法

1.1 研究对象

本研究采用决策树模型,模拟在30岁以上的英国德系犹太妇女中进行多基因面板检测的成本效果。根据每个易感基因相对危险度及现有指南[9],本文选取了BRCA1、BRCA2、TP53、PETN、STK11、CDH1、PALB2七个高风险乳腺癌易感基因作为面板基因。由于关于其他高风险人群突变率的研究报道较少,因此我们将研究背景定位于该方面报告比较多的德系犹太妇女,研究在英国德系犹太人群中进行多基因面板检测的经济性。

1.2 模型描述

图1展示了决策树模型框架,一条分支开始于NGS面板检测,另一条为无基因检测。由于BRCA1、BRCA2基因突变会一定程度上提高卵巢癌风险,因此我们将卵巢癌也纳入到模型中。根据现有指南,检测呈阳性的妇女会提供预防性输卵管—卵巢切除术(risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy,RRSO)来减少卵巢癌风险,或者预防性乳房切除术(risk-reducing mastectomy,RRM)、磁共振成像(magnetic resonance imaging,MRI )、乳房X线钼靶摄影检查来降低乳腺癌风险。所有分支事件的结果分为三种:患乳腺癌(breast cancer,BC)、患卵巢癌(ovarian cancer,OC)、无癌症(No BC or OC)。由于乳腺癌和卵巢癌同时发生的事件比较罕见,所以在模型中假设不会同时发生。

1.3 结果指标

总的结果指标有3个:(1)两种检测策略的平均癌症发生率(乳腺癌与卵巢癌癌症发生率);(2)两种检测策略的平均质量调整生命年(QALYs);(3)以无基因检测的成本和效果为对比基线的增量成本效果比(Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio,ICER)。这些衡量指标均是以个人为基础的平均指标,基因检测的人口总效应会应用到英国德系人口女性总数。英国的德系犹太女性据估计有114 400人[10],研究假设基因检测有70%的参与率[11],总人口效应会用单个人口效应乘以总参与人数求得。

图1 决策树模型注:非BRCA高风险基因阳性是指TP53/PETN/STK11/CDH1/PALB2基因呈阳性

1.4 数据来源

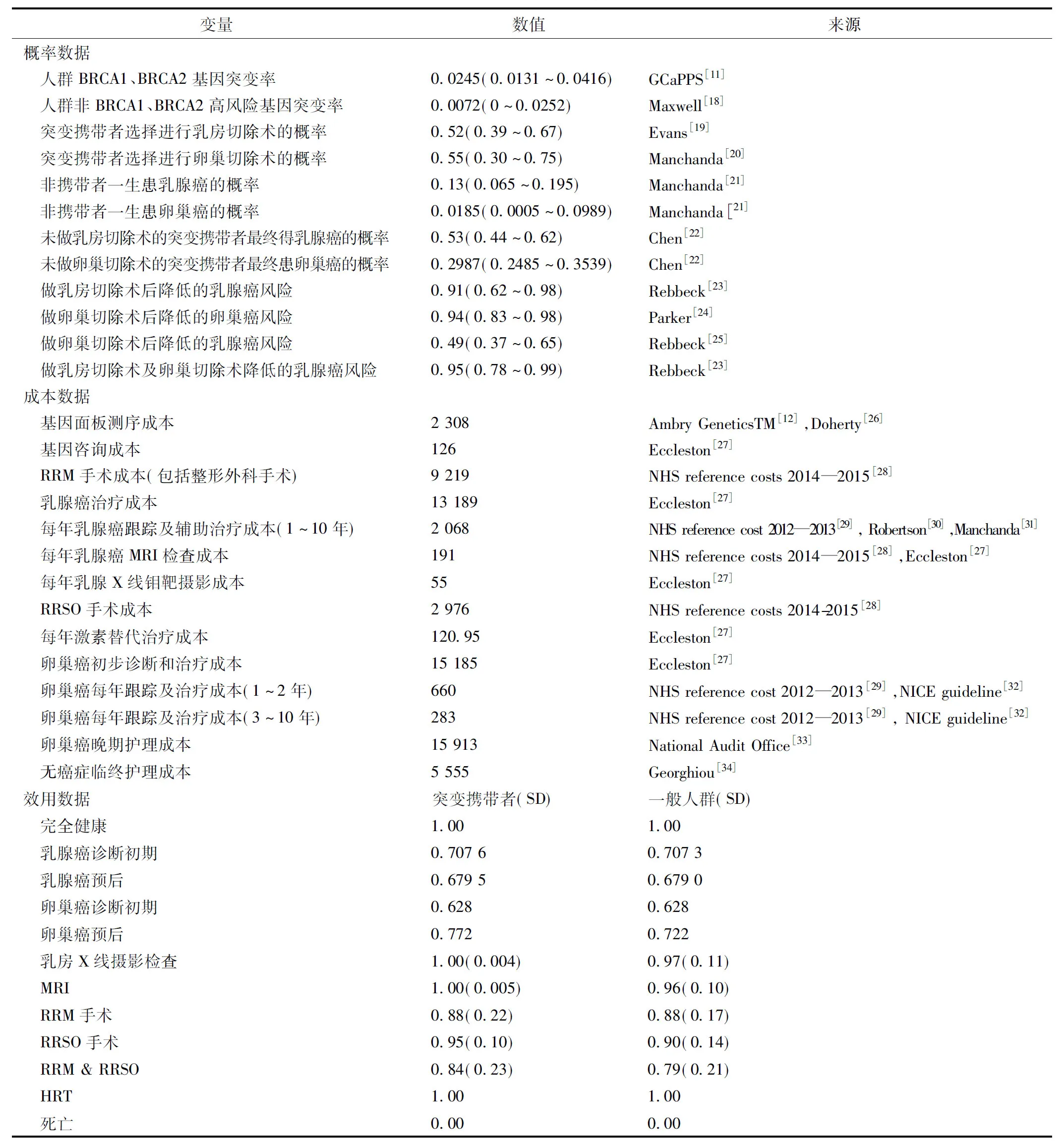

模型的参数主要从文献中获得,分为三种:概率参数、成本参数与效用参数。表1详细列出了各个参数的估计值与来源。其中,现阶段关于用多基因面板检测德系犹太人基因突变的研究还未出现,且该族群非BRCA1、BRCA2高风险基因突变率的数据报告也相对较少,因此对于人群非BRCA1、BRCA2高风险基因突变率本文采用了其他相关研究数据。所有的成本项目以2014年的英镑价格为准,其他年限的价格会通过GDP 平减指数调整至2014年,而其他货币则会通过国际购买力平价指数(Purchasing Power Parities,PPPs)将其转换成同等购买力的英镑。其中,基因面板测序的成本参考美国Ambry GeneticsTM公司开发的包含7个乳腺癌易感基因的面板测序产品BRCAPlus(BRCA1、 BRCA2、PTEN、TP53、CDH1、STK11、PALB2)的价格 ($3 300)。[12]

未患癌症女性生命预期数据来自于英国国家统计局发布的生命表[13],其他状态生命年则使用生存函数法衡量。乳腺癌各个阶段的效用值来自于NICE指南和文献[14-15],而卵巢癌各个阶段的效用值则来自于Havrilesky采用时间权衡法估计出的健康状态效用值[16],其他健康状态的效用值则来自于Grann[17]。

表1 模型参数及来源

1.5 贴现

本研究基于付费者的角度,时间范围为一生,研究两种检测策略在人群中的长期成本和健康效果。成本和效果均采用英国国家卫生保健研究院(National Institute for Health and Care Excellence,NICE)推荐的3.5%年贴现率进行贴现。[35]

1.6 成本效果分析

增量成本效果分析通过比较成本差异与效果差异的比值求得。通过比较ICER与成本效果阈值决定对人群进行基因测序是否具有成本效果。成本效果阈值是成本效果分析结果的外生评价标准,是判断干预措施是否具有经济性的标杆。本文采用NICE规定的£20 000/QALY~£30 000/QALY作为评价成本效果的阈值范围。[35]

1.7 敏感性分析

由于成本效果分析中模型及参数的不确定性,对结果会产生不同程度的影响。因此,需要对成本效果进行敏感性分析,以了解结果的稳健性。为了测试本研究模型参数的不确定性,会对模型进行单因素敏感性分析和概率性敏感性分析。单因素敏感性分析会通过改变模型中的每个单一参数来评估其对最后结果的影响。其中,概率及效用值会根据95%置信区间的变化范围或 ±10%的范围进行测试,成本则采用 ±30%的变化范围。概率性敏感性分析则同时测量所有变量值来进一步探索模型的不确定性。本文用beta分布模拟大部分概率变量及效用变量分布,logNormal分布模拟成本变量分布。用两条马尔科夫蒙特卡洛链(Markov Chain Monte Carlo,MCMC)模拟参数采样。在经过10 000次迭代(其中5 000次预迭代并抛弃), MCMC链达到收敛后,绘制成本效果平面图与成本效果可接受曲线。

1.8 统计分析

本研究采用R统计软件对数据进行分析。其中蒙特卡洛模拟是在R使用R2jags[36]、R2WinBUGS[37]程序包调用Jags软件进行MCMC模拟,概率敏感性成本效果分析及绘图则采用R中的BCEA软件包[38]完成。

2 结果

2.1 癌症发生率

由表2可以看出,多基因面板检测比无基因检测降低了1.1%的癌症发生率(乳腺癌0.75%,卵巢癌0.35%)。假设估计的114 000名英国德系犹太人群有70%的妇女经历基因检测,乘以总人口效应,多基因面板检测则分别减少了601例乳腺癌发病和283例卵巢癌发病,具有潜在的疾病预防效益。

表2 两种检测策略的模型基准值汇总

2.2 生命年与质量调整生命年

在生命年方面,英国国家统计局发布的生命表显示,未患癌症的女性预期寿命为83.41岁[13],因此我们假设普通英国德系犹太人群的平均预期寿命为83.41岁。对于任何一个30岁的德系犹太妇女,相对于无基因检测,多基因面板检测可以延长0.87个生命年和0.89个质量调整生命年,折现后的生命年和QALYs效益要比折现前小些,分别为0.38个生命年和0.39个质量调整生命年。

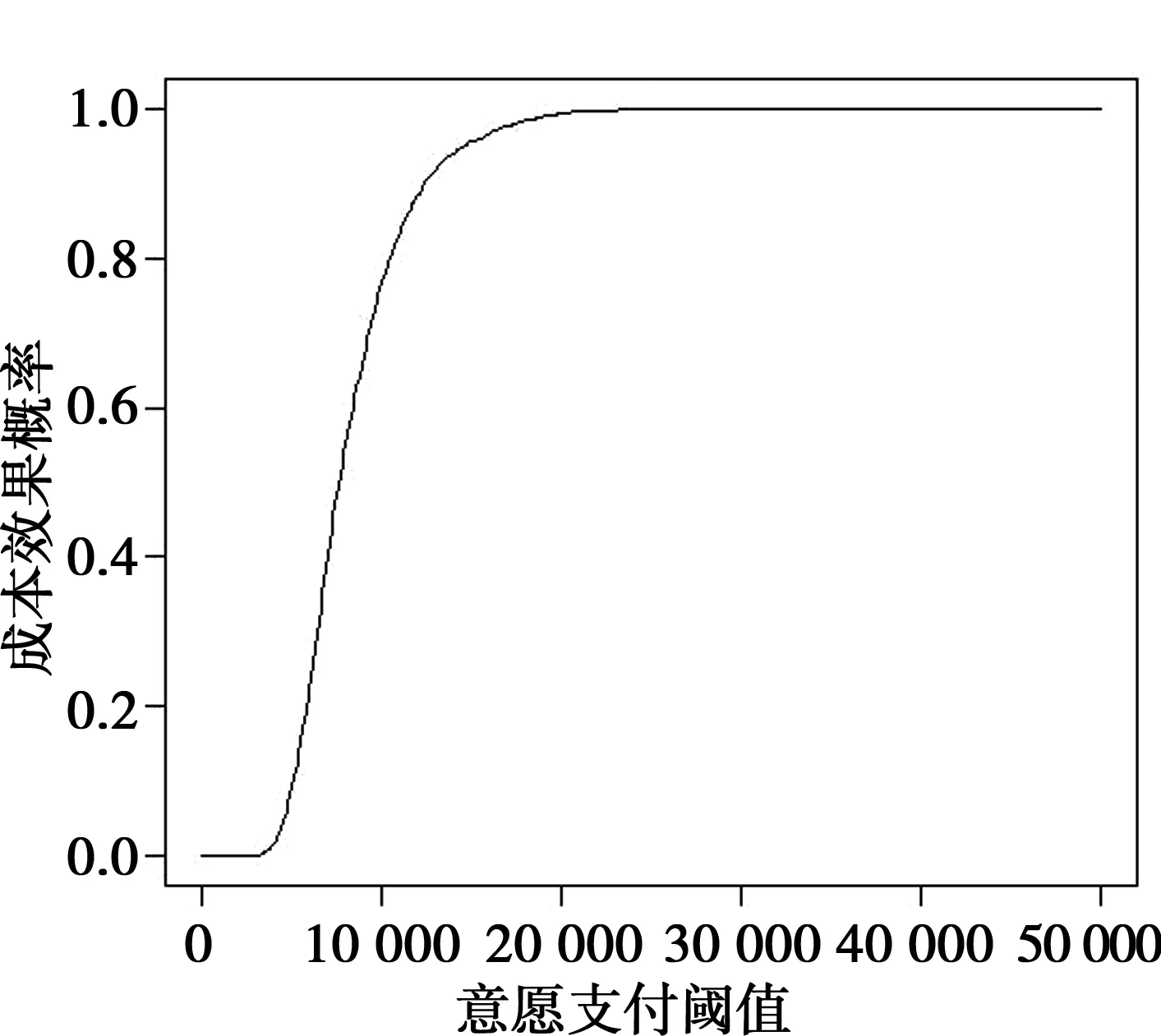

2.3 成本效果分析

由表3可以看出,多基因面板相对于无基因检测的增量成本效果比为 £6 766/QALY。NICE对成本效益规定的意愿支付阈值为 £20 000~£30 000/QALY。因此,与无基因检测相比,多基因面板具有成本效果。概率敏感性分析的结果显示,在 £10 000、£20 000和£30 000的阈值范围内,多基因面板具有成本效果的概率分别为76.9%、99.6%和99.9%。

表3 两种检测策略的成本效果对比(贴现后)

注:* 代表 NGS panel 与无基因检测对比的增量成本效果

2.4 敏感性分析

单因素敏感性结果显示患病风险、手术对癌症的降低风险、大部分成本及效用值的上下限值对总体结果的影响很小,模型在这些变量的上下限范围内均具有成本效果。然而,模型对于预防性手术的接受率、人群BRCA与非BRCA高风险基因突变率、基因面板测序成本具有较大的敏感性。虽然其带来的结果值变化范围幅度较大,但总体上仍具有成本效果。

图2与图3分别展示了模型的概率敏感性分析结果。成本效果平面图显示,大部分的模拟结果处于经济区域内,只有少量的点位于灰色部分外。成本效果可接受曲线图则显示在阈值范围内NGS面板具有90%以上的成本效果概率。平均增量成本和效果差异值也显示新的干预项即NGS面板增量效果值远低于上述阈值范围。

图2 成本效果平面图

图3 成本效果可接受曲线

3 讨论

本研究采用决策模型模拟了用多基因面板对30岁以上的英国德系犹太妇女人群进行预防性基因检测的成本与效果。结果显示,相对于无基因检测,多基因面板对于此类人群基因突变的检测具有 £6 766/QALY的增量成本效果,在现有标准阈值下具有成本效果。多基因面板检测的实施,将会减少884例癌症的发生,也会相对延长0.87个生命年和0.89个质量调整生命年。敏感性分析结果显示,易感基因突变率、预防性手术接受率、基因测序成本、乳房切除术的效用值等对结果影响较大,但并未影响模型结论。多基因面板总体上具有成本效果的概率为90%,这对于现阶段临床实践及公共健康管理具有潜在的指导意义。

本研究采用决策模型进行乳腺癌多基因面板和无基因检测成本效果比较,与其他研究相比,本研究同时考虑BRCA1、BRCA2、TP53、PETN、STK11、CDH1、PALB2七个高风险基因的检测,能诊断出更多高风险人群。本研究的时间范围为一生,足以反映长期成本和结果的区别。同时将乳腺癌和卵巢癌风险纳入到模型中,考虑更为全面。相对于其他同类研究,本研究还将激素替代疗法成本、无癌症临终治疗成本、癌症临终护理成本等纳入到成本考虑中,尽可能模拟现实成本。

本研究模型也存在很多限制。首先,本文纳入了TP53、PETN、STK11、CDH1、PALB2等基因检测。目前,还未发现有关德系犹太人上述基因突变的数据。采用其他高风险人群此类基因的突变率数据作替代,并不能真正代表德系犹太族群,因此这些中高度风险基因的检测带来的额外效益有待未来更多大规模临床和人口实验的考证。本研究只考虑了跟BRCA1、BRCA2基因相关的乳腺癌和卵巢癌,而与其他易感基因相关的癌症并未纳入模型中。如与PTEN相关的甲状腺癌,与PALB2相关的胰腺癌,可能低估了基因面板测序带来的潜在效益,未来的研究应纳入多种癌症风险评估和管理措施。同时,本研究也未考虑基因检测对家族成员的影响。另外,多基因检测面板中的基因有许多未明意义变种(variant of uncertain significance,VUS),这些未明意义变种的潜在风险和临床意义尚未有明确的指南指导,这些给基因检测结果的解释和管理带来了困难。因此,未来有必要进一步明确多基因面板测序的效益和限制,从而使患者和医生能做出明智的选择。另外,本研究假设面板检测的敏感性和特异度为100%,并未考虑假阴性和假阳性结果带来的影响。研究基于模型进行分析,模型的假设条件与实际情况存在一定差距。未来可以考虑加入动态Markov模型,纳入更多的相关癌症进行模型研究,或扩展到其他国家或地区人群,探索更多的可能性。

目前关于中国高风险人群突变率的报告还较少,而关于中国汉族人群的基因突变研究中尚未发现存在“始祖效应”的突变。我们的研究结果指出,基因检测对于以德系犹太妇女为代表的高风险突变携带者具有较大的成本效果,因此对于中国具有乳腺癌家族史的高风险人群,进行基因检测可以进一步明确他们的癌症风险,及时采取相关的预防措施,从而降低患病率,具有潜在的成本效益,未来有待进一步的卫生经济研究证实。

4 小结

本研究基于决策分析方法,建立了一个系统的比较多基因面板成本效果的模型。在现有研究证据下,对于突变率较高的德系犹太人群,二代多基因面板具有成本效果。因此,可以考虑在突变率较高的高风险人群中推广多基因面板检测。随着二代测序技术的深入发展,多基因检测的成本不断下降,多基因面板将具有更大的成本效果可能性。现在越来越多的研究和商业机构提供多癌症、多位点、多基因面板检测,未来应加强关于多基因面板成本效益的研究,为其进一步应用提供更多临床和经济学支持。

[1] Siegel R L, Miller K D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016[J]. Ca A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 2016, 66(1): 7-30.

[2] Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide:sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012[J]. International Journal of Cancer, 2015, 136(5): E359-E386.

[3] Ford D, Easton D F, Stratton M, et al. Genetic heterogeneity and penetrance analysis of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in breast cancer families[J]. The American Journal of Human Genetics, 1998, 62(3): 676-689.

[4] Hall M J, Reid J E, Burbidge L A, et al. BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in women of different ethnicities undergoing testing for hereditary breast-ovarian cancer[J]. Cancer, 2009, 115(10): 2222-2233.

[5] D’Andrea E, Marzuillo C, De Vito C, et al. Which BRCA genetic testing programs are ready for implementation in health care? A systematic review of economic evaluations[J]. Genetics in Medicine, 2016, 18(12): 1171-1180.

[6] Yorczyk A, Robinson L S, Ross T S. Use of panel tests in place of single gene tests in the cancer genetics clinic[J]. Clinical Genetics, 2015, 88(3): 278-282.

[7] Gallego C J, Shirts B H, Bennette C S, et al. Next-generation sequencing panels for the diagnosis of colorectal cancer and polyposis syndromes: a cost-effectiveness analysis[J]. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2015, 33(18): 2084-2091.

[8] Li Y, Bare L A, Bender R A, et al. Cost effectiveness of sequencing 34 cancer-associated genes as an aid for treatment selection in patients with metastatic melanoma[J]. Molecular Diagnosis & Therapy, 2015, 19(3): 169-177.

[9] Daly M B, Pilarski R, Axilbund J E, et al.Genetic/familial high-risk assessment: breast and ovarian, version 2.2015[J]. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2016, 14(2): 153-162.

[10] Graham D, Schmool M, Waterman S. Jews in Britain: a snapshot from the 2001 Census[R]. Institute for Jewish Policy Research, 2007.

[11] Manchanda R, Loggenberg K, Sanderson S, et al. Population testing for cancer predisposing BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations in the Ashkenazi-Jewish community: a randomized controlled trial[J]. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 2015, 107(1): dju379.

[12] Ambry Genetics Technology White Paper[EB/OL]. (2014-05-06)[2016-12-20]. http://www.ambrygen.com/

[13] Office for National Statistics. Lifetable for females in the UK[EB/OL]. [2016-12-20]. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/ lifeexpectancies

[14] Peasgood T, Ward S E, Brazier J. Health-state utility values in breast cancer[J]. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research, 2010, 10(5): 553-566.

[15] National Collaborating Centre for Cancer. Advanced breast cancer: diagnosis and treatment(developed for NICE)[EB/OL]. [2016-12-20]. http://www.guidance.nice.org.uk, 2009

[16] Havrilesky L J, Broadwater G, Davis D M, et al. Determination of quality of life-related utilities for health states relevant to ovarian cancer diagnosis and treatment[J]. Gynecologic Oncology, 2009, 113(2): 216-220.

[17] Grann V R, Patel P, Bharthuar A, et al. Breast cancer-related preferences among women with and without BRCA mutations[J]. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment, 2010, 119(1): 177.

[18] Maxwell K N, Wubbenhorst B, D’Andrea K, et al. Prevalence of mutations in a panel of breast cancer susceptibility genes in BRCA1/2-negative patients with early-onset breast cancer[J]. Genetics in Medicine, 2014, 17(8): 630-638.

[19] Evans D G R, Lalloo F, Ashcroft L, et al. Uptake of risk-reducing surgery in unaffected women at high risk of breast and ovarian cancer is risk, age, and time dependent[J]. Cancer Epidemiology & Prevention Biomarkers, 2009, 18(8): 2318-2324.

[20] Manchanda R, Burnell M, Abdelraheim A, et al. Factors influencing uptake and timing of risk reducing salpingo‐oophorectomy in women at risk of familial ovarian cancer: A competing risk time to event analysis[J]. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 2012, 119(5): 527-536.

[21] Manchanda R, Legood R, Burnell M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of population screening for BRCA mutations in Ashkenazi Jewish women compared with family history-based testing[J]. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 2015, 107(1): dju380.

[22] Chen S, Parmigiani G. Meta-analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 penetrance[J]. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2007, 25(11): 1329-1333.

[23] Rebbeck T R, Friebel T, Lynch H T, et al. Bilateral prophylactic mastectomy reduces breast cancer risk in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: the PROSE Study Group[J]. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2004, 22(6): 1055-1062.

[24] Parker W H, Feskanich D, Broder M S, et al. Long-term Mortality Associated with Oophorectomy compared with Ovarian Conservation in the Nurses’ Health Study[J]. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 2013,121(4): 709-716.

[25] Rebbeck T R, Kauff N D, Domchek S M. Meta-analysis of risk reduction estimates associated with risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy in BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers[J]. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 2009, 101(2): 80-87.

[26] Doherty J, Bonadies D C, Matloff E T. Testing for hereditary breast cancer: panel or targeted testing? Experience from a clinical cancer genetics practice[J]. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 2015, 24(4): 683-687.

[27] Eccleston A, Bentley A, Dyer M, et al. A discrete event simulation to evaluate the cost effectiveness of germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 testing in UK women with ovarian cancer[J]. BioRxiv, 2016, 20(4): 567-576.

[28] NHS. National Schedule of Reference Costs: 2014-15 [EB/OL]. [2016-12-20]. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/nhs-reference-costs-2014-to-2015

[29] Department of Health. NHS Reference Costs 2012-2013[EB/OL]. [2016-12-20]. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/261 154/nhs_reference_costs_2012-13_acc.pdf

[30] Robertson C, Ragupathy S K A, Boachie C, et al. The clinical effectiveness and cost effectiveness of different surveillance mammography regimens after the treatment for primary breast cancer: systematic reviews registry database analyses and economic evaluation[J]. Health Technology Assessment (Winchester, England), 2011, 15(34):1-7.

[31] Manchanda R, Legood R, Antoniou A C, et al.Specifying the ovarian cancer risk threshold of ‘premenopausal risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy’for ovarian cancer prevention: a cost-effectiveness analysis[J]. Journal of Medical Genetics, 2016: 591-599.

[32] NICE. Ovarian cancer: the recognition and initial management of ovarian cancer.Vol CG122[EB/OL].[2016-12-20]. https://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/CG122

[33] NAO. End of life care[EB/OL].[2016-12-20]. https://www.nao.org.uk/wp content/uploads/2008/11/07081043.pdf, 2008

[34] Georghiou T, Bardsley M. Exploring the cost of care at the end of life[R]. London: Nuffield Trust Research Report, 2014.

[35] National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Guide to the methods of technology appraisal 2013[EB/OL]. [2016-12-10]. https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg9/chapter/the-reference-case

[36] Su Y S, Yajima M. R2jags: Using R to run ‘JAGS’[R]. 2015.

[37] Sturtz S, Ligges U, Gelman A. R2WinBUGS: a package for running WinBUGS from R[J]. Journal of Statistical Software, 2005, 12(3): 1-16.

[38] Baio G. BCEA: A package to run Bayesian Cost-Effectiveness Analysis in R[EB/OL]. [2016-12-20]. http://www.statistica.it/gianluca/BCEA/BaioECHE.pdf

Cost-effectivenessanalysisofbreastcancermulti-genepanelsequencing

DUChun-yan

InstituteofChineseMedicalSciences,UniversityofMacau,Macau999078,China

Objective: To model and evaluate the cost-effectiveness of next-generation sequencing (NGS) panel for the screening of breast and ovarian cancer using the decision-making model amongst UK Ashkenazi Jews (AJ) women in the German community, determining whether a multi-gene panel would be cost-effective in patients referred to high-risk of breast cancer when compared with no testing program. Methods: Based on the population epidemiology and cost data in the United Kingdom, a decision-analytic model was developed to compare lifetime costs and benefits associated with NGS panel. The cost-effectiveness analysis was analyzed from a payer’s perspective across a lifetime horizon. Multiple source data were used for estimating cancer incidence, total costs, life-years, quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) and incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER). Costs were reported at 2014 prices and discounted at 3.5%. Deterministic and probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA) based on Monte Carlo Simulations were performed to evaluate the robustness of model. Results: In the base-case analysis, compared with no screening strategy, multi-gene panel test lowered the cancer incidence by 1.1% (0.75% for breast cancer, 0.47% for ovarian cancer), and gained an additional 0.87 life years and 0.89 QALYs, resulting in a discounted ICER of ?6766/QALY. Considering 70% testing uptake, this led to 601 fewer breast cancer cases and 283 fewer ovarian cancer cases. One-way sensitivity analysis indicated that the model was robust to variations for most of model parameters. The penetrance rate of breast cancer susceptibility genes was an important factor affecting overall results of the model. PSA showed that the probability for NGS panel being cost-effective at the threshold of ?20000/QALY-£30000/QALY was over than 90%, compared with no screening strategy. Conclusion: NGS panel testing of breast cancer was cost-effective compared with no screening strategy, especially for those AJ women with high mutation rates.

Breast cancer; Cost-effectiveness analysis; Decision-analytic model; Next-generation sequencing panel

杜春艳,女(1990年—),硕士研究生,主要研究方向为卫生经济学。E-mail:mb45820@connect.umac.mo

R197

A

10.3969/j.issn.1674-2982.2017.11.010

2017-03-27

2017-06-27]

(编辑 赵晓娟)