硒蛋白与神经退行性疾病

杨玉洁, 李 楠

深圳大学生命与海洋科学学院, 广东 深圳 518060

硒蛋白与神经退行性疾病

杨玉洁, 李 楠*

深圳大学生命与海洋科学学院, 广东 深圳 518060

硒蛋白是一类含有硒代半胱氨酸的蛋白质,以硒元素为活性中心,利用其强还原性参与多种生物代谢过程中的氧化还原反应。目前在人体中已发现的硒蛋白有25种,其中部分硒蛋白的生理功能尚不明确。脑组织是硒蛋白分布最为丰富的人体器官之一,采用基因敲除的方法研究硒蛋白的生理功能,发现多种硒蛋白缺失都能引起小鼠认知能力损伤或运动功能障碍。由于脑组织代谢过程中会产生大量的活性氧(reactive oxygen species,ROS),其产生的氧化压力被认为是神经退行性疾病产生和发展的重要诱因之一,而清除活性氧是某些硒蛋白的主要生理功能,因此硒蛋白在神经退行性疾病中的作用受到了越来越多的关注。综述了硒蛋白的生理功能,及其与多种神经退行性疾病的联系,以期为硒蛋白在治疗神经退行性疾病中的应用提供参考。

硒蛋白;神经退行性疾病;氧化应激;阿尔茨海默症;帕金森症

硒蛋白(selenoprotein)是指一类含有硒代半胱氨酸(selenocysteine,Sec)的蛋白质,Sec是目前在生物体内被发现的第21种天然氨基酸,它由传统意义上的终止密码子UGA所编码,在特定的翻译条件下,Sec能被特异性的硒代半胱氨酸转运RNA(tRNAsec)转入到合成中的硒蛋白多肽链上。与半胱氨酸相似,Sec也具有还原性,其在分子结构上可以看作是半胱氨酸巯基中的硫元素被硒元素取代的形式。而实际的生物合成过程中,Sec-tRNASec是由单磷酸硒与丝氨酰-tRNASec反应而形成的,这个过程需要硒代半胱氨酸合酶的催化。

1957年,Schwarz和Foltz[1]发现食物中缺乏硒元素会引起大鼠肝坏死。1973年,Flohe等[2]首次发现谷胱甘肽过氧化物酶(glutathione peroxidase,GPx)是一种硒酶,并且硒代半胱氨酸是其催化活性的中心。在中国东北地区发现的克山病,就是由于饮食中硒缺乏造成人体GPx1表达降低,导致患者易感染柯萨奇病毒,因而引起的心肌疾病[3]。研究表明,硒蛋白在甲状腺激素代谢、脑组织发育、男性生殖、免疫功能以及能量代谢等多种生理过程中都具有重要作用,它们通过参与多种氧化还原反应,使体内的氧化压力得到中和,而硒代半胱氨酸赋予了它们这种催化活性。

脑组织是人体中硒含量最丰富的器官之一,在食物中缺乏硒元素的情况下,人体肝脏、肾脏和肺等多个器官的硒元素含量和硒蛋白表达水平都会降低,但是脑组织中仍然能够维持较高的硒元素含量和较稳定的硒蛋白活性水平[4]。说明脑组织对于硒元素的摄取具有特别的优势。通过对转录组的研究发现,脑组织中的神经元、星形胶质细胞和小胶质细胞均表达多种硒蛋白,尤其在海马、嗅区和皮质中硒蛋白含量最为丰富[5]。这些硒蛋白在中枢神经系统中具有抗氧化的功能,大脑中硒蛋白表达水平的降低会造成神经元产生不可逆的损伤,导致认知障碍、抑郁和焦虑[6]。

1 硒蛋白的合成

硒代半胱氨酸含有微量元素硒,而且其编码密码子是传统意义上的终止密码子UGA,因此其合成过程及进入蛋白质多肽链的过程较为独特。硒蛋白的合成过程可以分为两个主要步骤:第一步是将硒与特异性的tRNA(tRNASec)相连接形成Sec-tRNASec,第二步是通过Sec-tRNASec将Sec插入到正在翻译形成的硒蛋白中[7]。

图1 硒代半胱氨酸-tRNA合成过程Fig.1 The process of Sec-tRNA biological synthesis.注:SerS:丝氨酰-tRNA合成酶;PSTK:磷酸丝氨酰-tRNA激酶;SPS2:硒磷酸合成酶-2;SecS:硒代半胱氨酸合酶。

Sec-tRNASec需要在密码子UGA的指导下才能够将硒代半胱氨酸插入到蛋白质多肽链中。UGA通常是终止密码子,但在硒蛋白mRNA的3′非翻译区存在一个特殊的茎环结构,称为硒代半胱氨酸插入序列(Sec insertion sequence, SECIS),SECIS是一个顺式作用原件,当硒蛋白mRNA与核糖体结合后,它与两个反式作用因子EFsec(Sec-specific elongation factor)及SBP2(SECIS binding proteins 2)组成复合体。SBP2能与核糖体稳定结合,同时通过其RNA结合结构域与SECIS序列高度特异性结合,EFsec与SBP2相互作用并募集Sec-tRNASec,在与密码子UGA所对应的位置,将Sec置入正在生成的硒蛋白多肽链中。真核生物中硒蛋白的合成较为复杂,至今Sec-tRNASec、SECIS和UGA 三者之间相互作用的确切机制尚不清楚[8]。

由于硒蛋白在多种生理过程中都起到重要作用,因此影响硒蛋白合成会引发各种疾病。例如,tRNAsec由Trsp基因编码,在小鼠体内敲除该基因会造成胚胎致死[9]。而SBP2的突变会引起硒蛋白减少,进而导致脱碘酶(deiodinase-2,DIO2)活性降低和甲状腺激素代谢异常,以及青春期前生长停滞[10]。另外,SecS突变会导致大脑和小脑的萎缩[11]。

2 硒蛋白的功能

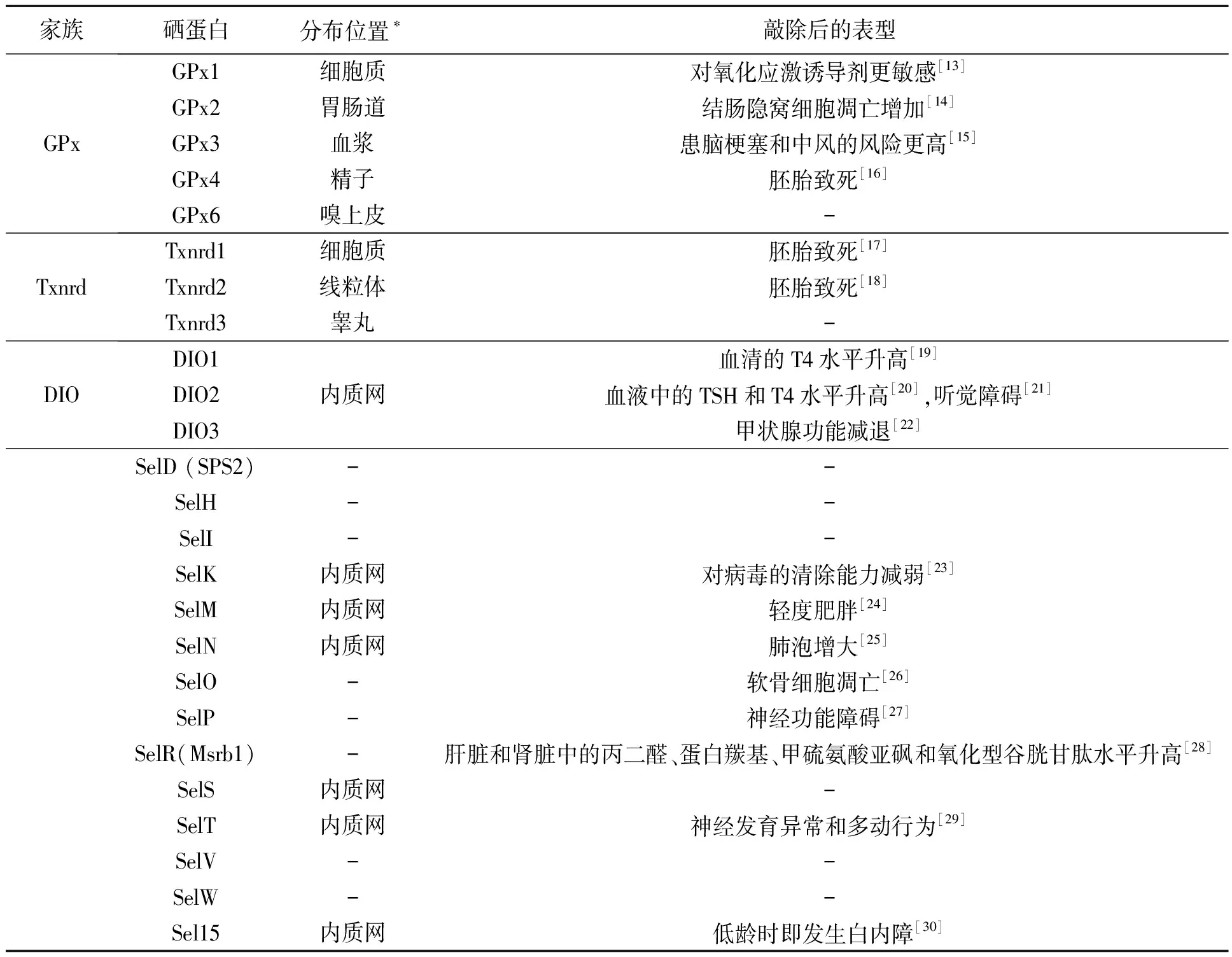

通过全基因组序列分析,发现含有SECIS序列的基因共有25个[12],它们分别编码了25种不同的硒蛋白:谷胱甘肽过氧化物酶(glutathione peroxidase,GPx1-4、GPx6)、硫氧还蛋白还原酶(thioredoxin reductases,Txnrd1-3)、脱碘酶(deiodinase,DIO1-3)、Sel15(15-kDa selenoprotein)、SelD(SPS2)、SelH、SelI、SelK、SelM、SelN、SelO、SelP、SelR、SelS、SelT、SelV、SelW。表1总结了某些硒蛋白敲除后的小鼠表型。

GPxs的主要功能是利用谷胱甘肽还原过氧化氢等活性氧(reactive oxygen species,ROS)[31]。Txnrds含有黄素腺嘌呤二核苷酸(flavin adenine dinucleotide,FAD)结构域,是依赖还原型烟酰胺腺嘌呤二核苷酸磷酸(NADPH)的二聚体的硒酶。它主要通过消耗NADPH来使氧化的硫氧还蛋白得到还原[32]。DIOs对甲状腺激素的合成代谢具有非常重要的调节作用。其中DIO1和DIO2通过外环脱碘酶反应,将3,5,3′,5′-四碘甲腺原氨酸(T4)转化为3,3′,5′-三碘甲腺原氨酸(T3)从而促进甲状腺激素的成熟,而DIO3则通过内环脱碘酶反应,将T3转化为无活性的T2或将T4转化为无活性的反式T3[33]。

表1 硒蛋白敲除的小鼠表型Table 1 The phonotype induced by individual selenoprotein knockout in mice.

注:*硒蛋白分布不仅限于本表所标注的区域;“-”表示无数据

除了以上3个硒蛋白家族,SelP的功能目前也比较清楚,它含有10个Sec残基,可以作为硒元素的转运载体,通过载脂蛋白E受体2(ApoER2)介导的内吞作用将硒从肝脏运送到其他组织器官[34],脑组织维持较高硒含量也依赖于SelP的表达。SelP及ApoER2的敲除会导致小鼠肌肉痉挛、行动异常和自发性抽搐[35]。

Sel15、SelK、SelM、SelN、SelS、SelT及DIO2这7种硒蛋白分布于内质网中[36]。Sel15包含硫氧还蛋白样折叠(Txn-like folds)结构,具有氧化还原酶的功能;SelK是一个钙激活蛋白酶的靶标蛋白;SelM与Sel15具有同源性,参与能量代谢过程;SelN通过与兰尼碱受体的相互作用调节肌肉细胞的钙稳态;SelS能将错误折叠的蛋白质从内质网运输到细胞质;SelT也具有硫氧还蛋白样折叠结构,在小鼠的胚胎发育期,SelT在脑组织中表达水平较高,出生后表达水平有所降低。

此外,SelH位于细胞核中,是DNA结合蛋白,能够调控基因的表达、参与谷胱甘肽合成和肝脏解毒[37]。SelI是一种乙醇胺磷酸转移酶,它的功能是产生膜磷脂和鞘磷脂[38]。SelR是蛋氨酸亚砜还原酶家族成员,可介导氧化型蛋氨酸残基的还原[39]。SelW主要存在于骨骼肌和心脏中[40],能够与谷胱甘肽结合并抑制过氧化氢的细胞毒性。还有一些硒蛋白如SelO、SelV,其功能尚不清楚。

3 硒蛋白与神经退行性疾病

3.1阿尔茨海默症

阿尔茨海默症(Alzheimer’s disease, AD)的临床症状表现为记忆的逐渐丧失以及认知能力的衰退。AD患者的脑组织切片中出现大量β-淀粉样蛋白(Amyloid-β,Aβ)沉积形成的老年斑,以及由过度磷酸化的微管结合蛋白(tubulin associated unit,Tau)聚集形成的神经纤维缠结(neurofibrillary tangles,NFT)。淀粉样前体蛋白(amyloid-precursor protein,APP)和早老素1/2(presenilin-1/2)的某些突变能导致遗传性的早发型AD。而载脂蛋白E(apolipoprotein E,ApoE)等基因突变则与迟发型AD相关。这些突变均与Aβ1-42的过量产生和积累有关。Aβ假说认为Aβ寡聚体具有神经细胞毒性,能够引起神经元损伤和凋亡。研究发现,AD患者脑中硒的浓度仅为同龄正常人的60%[41]。

APP是Aβ的前体蛋白,APP经β-分泌酶剪切生成sAPPβ,再经γ-分泌酶剪切形成Aβ1-40、Aβ1-42,其中Aβ1-42更易于聚集。β-分泌酶和γ-分泌酶的降低都能减少Aβ的产生。ERK是γ-分泌酶的负调节因子,研究表明,亚硒酸钠可激活ERK,抑制内源性γ-分泌酶的活性[42]。在AD模型小鼠的食物中添加硒代蛋氨酸,与对照组相比,其脑组织的硒酶活性增强,β-分泌酶的水平下调,Aβ的产生和沉积都显著减少[43]。另外,硒代蛋氨酸在小鼠体内还可以通过激活PI3K/Akt信号通路抑制糖原合酶激酶-3β(GSK-3β)的活性从而促进神经再生[44]。Chen等[45]还发现SelM能够抑制Aβ的聚集及其在HEK293T细胞内引起的氧化压力。Wang等[46]采用荧光共振(FERT)和免疫共沉淀技术发现SelR与Aβ1-42在体外具有直接的相互作用,说明SelR可能对Aβ的聚集具有调节作用。Du等[47]则发现SelP的组蛋白富集区能够结合铜离子,从而抑制铜离子介导的Aβ纤维化聚集及其神经毒性。这些结果证明硒蛋白可能通过多种途径调节Aβ的聚集,并影响神经元的功能。

而Tau蛋白是微管结合蛋白,但在AD病理条件下,Tau蛋白的过度磷酸化使其与微管脱离,并进一步在神经元内形成NFT,诱发神经元凋亡。硒代蛋氨酸不仅能够影响Aβ的产生,还能够降低Tau蛋白的磷酸化水平。经硒代蛋氨酸处理后,AD模型小鼠认知能力显著提高,并且通过调节GSK-3β和蛋白磷酸酯酶2A(protein phosphatase 2A,PP2A)活性抑制了Tau蛋白过度磷酸化。以上结果说明硒蛋白对Tau蛋白的聚集也具有一定调节作用。

3.2帕金森氏综合症

帕金森氏综合症(Parkinson’s disease, PD)的主要病理特征是α-突触核蛋白(α-synuclein)纤维聚集形成路易小体(Lewy’s body),造成中脑黑质中多巴胺能神经元死亡,导致严重的运动功能障碍。PD的确切致病机制仍不清楚,氧化应激、线粒体损伤、蛋白酶体功能障碍和α-突触核蛋白聚集等都可能是导致神经系统病变的原因[48]。在PD病人中,由于多巴胺代谢产生过氧化氢和超氧化物歧化的副产物,同时还自发地产生高活性的醌分子[49]。因此,氧化应激可能是帕金森氏病(PD)发病机制的核心因素。

Zhang等[50]发现PD小鼠模型的黑质中有17种硒蛋白的mRNAs水平发生明显下降,并且没有一种硒蛋白的表达上调。Imam和Ali[51]发现缺硒会导致PD模型小鼠的多巴胺能神经末梢的化学损伤更为严重。而Ellwanger等[52]则发现通过补充亚硒酸,可以降低百枯草PD模型大鼠的DNA损伤程度并减轻其动作迟缓的症状。Sun[53]在美国的48个州做了一项调查研究土壤中硒、锶和镁浓度与美国帕金森病死亡率的关系,结果显示土壤高硒和高镁浓度有助于减少PD的死亡率并且对PD患者有益。另外还有研究表明,SelT在PD小鼠模型中能够保护多巴胺能神经元[54]。

3.3其他神经退行性疾病

研究发现血清中的硒元素水平与癫痫(Epilepsy)发作呈负相关,硒缺乏导致少儿癫痫的发作风险增加。这与动物实验结果相吻合,在癫痫动物模型中,硒缺乏会促进癫痫抽搐,而补充硒能够减少癫痫抽搐[55]。另外脑组织特异性敲除所有硒蛋白会导致严重的癫痫发作[56],在神经元中条件性敲除GPx4会使动物在出生后12 d开始出现癫痫性抽搐[57]。

值得注意的是,血清中无机硒的水平与SelP结合硒的水平并不一定是正相关的,研究也发现血清无机硒的水平过高的同时,SelP结合硒的浓度会降低。这种情况下,可能会使肌萎缩性侧索硬化症(amyotrophic lateral sclerosis)的患病风险上升[58]。

另外,亨廷顿舞蹈症(Huntington’s disease,HD)患者的网纹体中GPx1和GPx6活性显著升高[59]。在HD模型小鼠中,补充硒能够减轻氧化应激和脂质的过氧化,并有效降低喹啉酸诱导的神经退行性病变[60]。

4 展望

硒蛋白是一类非常独特的具有强还原性的蛋白质,脑组织中非正常范围内的硒元素水平变化会造成各种神经疾病,利用基因敲除方法也证明多种硒蛋白对于神经系统的正常运转是必不可少的,比如SecS的敲除会导致中枢神经系统的异常发育以及SelP的敲除会引起神经功能损伤。另外,还有多种硒蛋白的敲除会导致小鼠的胚胎致死,而这些硒蛋白在脑组织中的确切功能可能还需要通过条件性敲除的方法进行进一步研究。很多证据表明,硒蛋白在多种神经退行性疾病的病理过程中起到了重要的作用,但是由于这些疾病的病因极其复杂,硒蛋白确切的分子生物学作用仍有待继续探究。另外,不同地域人群的硒元素摄入有着很大的差异,如何科学补硒,以及补充硒元素是否能够在人群中预防或治疗神经退行性疾病也是需要继续研究的重要课题。

[1] Schwarz K, Foltz C M. Selenium as an integral part of factor-3 against dietary necrotic liver degeneration[J]. J. Am. Chem. Soc., 1957, 79(12): 3292-3293.

[2] Flohe L, Günzler W A, Schock H H. Glutathione peroxidase: a selenoenzyme[J]. FEBS Lett., 1973, 32(1): 132-134.

[3] Moghadaszadeh B, Beggs A H. Selenoproteins and their impact on human health through diverse physiological pathways[J]. Physiology, 2006, 21(5): 307-315.

[4] Brigelius-Flohé R. Tissue-specific functions of individual glutathione peroxidases[J]. Free Radical Bio. Med., 1999, 27(9): 951-965.

[5] Zhang Y, Zhou Y, Schweizer U,etal.. Comparative analysis of selenocysteine machinery and selenoproteome gene expression in mouse brain identifies neurons as key functional sites of selenium in mammals[J]. J. Biol. Chem., 2008, 283(4): 2427-2438.

[6] Rayman M P. The argument for increasing selenium intake[J]. Proc. Nutr. Soc., 2002, 61(2): 203-215.

[7] Labunskyy V M, Hatfield D L, Gladyshev V N. Selenoproteins: Molecular pathways and physiological roles[J]. Physiol. Rev., 2014, 94(3): 739-777.

[8] Ashrafi M R, Shabanian R, Abbaskhanian A,etal.. Selenium and intractable epilepsy: Is there any correlation?[J]. Pediatr. Neurol., 2007, 36(1): 25-29.

[9] Bösl M R, Takaku K, Oshima M,etal.. Early embryonic lethality caused by targeted disruption of the mouse selenocysteine tRNA gene (Trsp)[J]. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 1997, 94(11): 5531-5534.

[10] Dumitrescu A M, Liao X H, Abdullah M S Y,etal.. Mutations in SECISBP2 result in abnormal thyroid hormone metabolism[J]. Nat. Genet., 2005, 37(11): 1247-1252.

[11] Agamy O, Zeev B B, Lev D,etal.. Mutations disrupting selenocysteine formation cause progressive cerebello-cerebral atrophy[J]. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 2010, 87(4): 538-544.

[12] Kryukov G V, Castellano S, Novoselov S V,etal.. Characterization of mammalian selenoproteomes[J]. Science, 2003, 300(5624): 1439-1443.

[13] de Haan J B, Bladier C, Griffiths P,etal.. Mice with a homozygous null mutation for the most abundant glutathione peroxidase, Gpx1, show increased susceptibility to the oxidative stress-inducing agents paraquat and hydrogen peroxide[J]. J. Biol. Chem., 1998, 273(35): 22528-22536.

[14] Florian S, Krehl S, Loewinger M,etal.. Loss of GPx2 increases apoptosis, mitosis, and GPx1 expression in the intestine of mice[J]. Free Radical Biol. Med., 2010, 49(11): 1694-1702.

[15] Jin R C, Mahoney C E, Coleman Anderson L,etal.. Glutathione peroxidase-3 deficiency promotes platelet-dependent thrombosisinvivo[J]. Circulation, 2011, 123(18): 1963-1973.

[16] Yant L J, Ran Q T, Rao L,etal.. The selenoprotein GPX4 is essential for mouse development and protects from radiation and oxidative damage insults[J]. Free Radical Biol. Med., 2003, 34(4): 496-502.

[17] Jakupoglu C, Przemeck G K H, Schneider M,etal.. Cytoplasmic thioredoxin reductase is essential for embryogenesis but dispensable for cardiac development[J]. Mol. Cell. Biol., 2005, 25(5): 1980-1988.

[18] Bréhélin C, Laloi C, Setterdahl A T,etal.. Cytosolic, mitochondrial thioredoxins and thioredoxin reductases in Arabidopsis thaliana[J]. Photosynth. Res., 2004, 79(3): 295-304.

[19] Schneider M J, Fiering S N, Thai B,etal.. Targeted disruption of the type 1 selenodeiodinase gene (Dio1) results in marked changes in thyroid hormone economy in mice[J]. Endocrinology, 2006, 147(1): 580-589.

[20] Schneider M J, Fiering S N, Pallud S E,etal.. Targeted disruption of the type 2 selenodeiodinase gene (DIO2) results in a phenotype of pituitary resistance to T4[J]. Mol. Endocrinol., 2001, 15(12): 2137-2148.

[21] Ng L, Goodyear R J, Woods C A,etal.. Hearing loss and retarded cochlear development in mice lacking type 2 iodothyronine deiodinase[J]. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 2004, 101(10): 3474-3479.

[22] Hernandez A, Martinez M E, Fiering S,etal.. Type 3 deiodinase is critical for the maturation and function of the thyroid axis[J]. J. Clin. Invest., 2006, 116(2): 476-484.

[23] Verma S, Hoffmann F W, Kumar M,etal.. Selenoprotein K knockout mice exhibit deficient calcium flux in immune cells and impaired immune responses[J]. J. Immunol., 2011, 186(4): 2127-2137.

[24] Pitts M W, Reeves M A, Hashimoto A C,etal.. Deletion of selenoprotein M leads to obesity without cognitive deficits[J]. J. Biol. Chem., 2013, 288(36): 26121-26134.

[25] Moghadaszadeh B, Rider B E, Lawlor M W,etal.. Selenoprotein N deficiency in mice is associated with abnormal lung development[J]. FASEB J., 2013, 27(4): 1585-1599.

[26] Yan J, Fei Y, Han Y,etal.. Selenoprotein O deficiencies suppress chondrogenic differentiation of ATDC5 cells[J]. Cell Biol. Int., 2016, 40(10): 1033-1040.

[27] Hill K E, Zhou J, McMahan W J,etal.. Neurological dysfunction occurs in mice with targeted deletion of the selenoprotein P gene[J]. J. Nutr., 2004, 134(1): 157-161.

[28] Fomenko D E, Novoselov S V, Natarajan S K,etal.. MsrB1 (methionine-R-sulfoxide reductase 1) knock-out mice: roles of MsrB1 in redox regulation and identification of a novel selenoprotein form[J]. J. Biol. Chem., 2009, 284(9): 5986-5993.

[29] Castex M T, Arabo A, Bénard M,etal.. Selenoprotein T deficiency leads to neurodevelopmental abnormalities and hyperactive behavior in Mice[J]. Mol. Neurobiol., 2016, 53(9): 5818-5832.

[30] Kasaikina M V, Fomenko D E, Labunskyy V M,etal.. Roles of the 15-kDa selenoprotein (Sep15) in redox homeostasis and cataract development revealed by the analysis of Sep 15 knockout mice[J]. J. Biol. Chem., 2011, 286(38): 33203-33212.

[31] Lu J, Holmgren A. Selenoproteins[J]. J. Biol. Chem., 2009, 284(2): 723-727.

[32] Nishiyama A, Masutani H, Nakamura H,etal.. Redox regulation by thioredoxin and thioredoxin-binding proteins[J]. IUBMB Life, 2001, 52(1): 29-33.

[33] Bianco A C, Salvatore D, Gereben B,etal.. Biochemistry, cellular and molecular biology, and physiological roles of the iodothyronine selenodeiodinases[J]. Endocr. Rev., 2002, 23(1): 38-89.

[34] Burk R F, Hill K E. Selenoprotein P-expression, functions, and roles in mammals[J]. BBA-Gen. Subjects, 2009, 1790(11): 1441-1447.

[35] Nakayama A, Hill K E, Austin L M,etal.. All regions of mouse brain are dependent on selenoprotein P for maintenance of selenium[J]. J. Nutr., 2007, 137(3): 690-693.

[36] Shchedrina V A, Zhang Y, Labunskyy V M,etal.. Structure-function relations, physiological roles, and evolution of mammalian ER-resident selenoproteins[J]. Antioxid. Redox Sign., 2010, 12(7): 839-849.

[37] Novoselov S V, Kryukov G V, Xu X M,etal.. Selenoprotein H is a nucleolar thioredoxin-like protein with a unique expression pattern[J]. J. Biol. Chem., 2007, 282(16): 11960-11968.

[38] Horibata Y, Hirabayashi Y. Identification and characterization of human ethanolaminephosphotransferase1[J]. J. Lipid Res., 2007, 48(3): 503-508.

[39] Novoselov S V, Kim H Y, Hua D,etal.. Regulation of selenoproteins and methionine sulfoxide reductases A and B1 by age, calorie restriction, and dietary selenium in mice[J]. Antioxid. Redox Sign., 2010, 12(7): 829-838.

[40] Gu Q P, Sun Y, Ream L W,etal.. Selenoprotein W accumulates primarily in primate skeletal muscle, heart, brain and tongue[J]. Mol. Cell. Biochem., 2000, 204(1): 49-56.

[41] Hawkes W C, Hornbostel L. Effects of dietary selenium on mood in healthy men living in a metabolic research unit[J]. Biol. Psychiat., 1996, 39(2): 121-128.

[42] Tung Y T, Hsu W M, Wang B J,etal.. Sodium selenite inhibits gamma-secretase activity through activation of ERK[J]. Neurosci. Lett., 2008, 440(1): 38-43.

[43] Zhang Z H, Chen C, Wu Q Y,etal.. Selenomethionine reduces the deposition of β-amyloid plaques by modulating β-secretase and enhancing selenoenzymatic activity in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease[J]. Metallomics, 2016, 8(8): 782-789.

[44] Zheng R, Zhang Z H, Chen C,etal.. Selenomethionine promoted hippocampal neurogenesis via the PI3K-Akt-GSK3β-Wnt pathway in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease[J]. Biochem. Bioph. Res. Co., 2017, 485(1): 6-15.

[45] Chen P, Wang R R, Ma X J,etal.. Different forms of selenoprotein M differentially affect Aβ aggregation and ROS generation[J]. Int. J. Mol. Sci., 2013, 14(3): 4385-4399.

[46] Wang C, Chen P, He X,etal.. Direct interaction between selenoprotein R and Aβ 42[J]. Biochem. Bioph. Res. Co., 2017, 489(4): 509-514.

[47] Du X, Wang Z, Zheng Y,etal.. Inhibitory effect of selenoprotein P on Cu(+)/Cu(2+)-induced Aβ 42 aggregation and toxicity[J]. Metallomics, 2013, 5(7): 861-870.

[48] Ellwanger J H, Franke S I R, Bordin D L,etal.. Biological functions of selenium and its potential influence on Parkinson’s disease[J]. Annu. Acad. Bras. Cienc., 2016, 88(3): 1655-1674.

[49] Stokes A H, Hastings T G, Vrana K E. Cytotoxic and genotoxic potential of dopamine[J]. J. Neurosci. Res., 1999, 55(6): 659-665.

[50] Zhang X, Ye Y L, Zhu H,etal.. Selenotranscriptomic analyses identify signature selenoproteins in brain regions in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease[J]. PLoS ONE, 2016, 11(9): e0163372.

[51] Imam S Z, Ali S F. Selenium, an antioxidant, attenuates methamphetamine-induced dopaminergic toxicity and peroxynitrite generation[J]. Brain Res., 2000, 855(1): 186-191.

[52] Ellwanger J H, Molz P, Dallemole D R,etal.. Selenium reduces bradykinesia and DNA damage in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease[J]. Nutrition, 2015, 31(2): 359-365.

[53] Sun H. Association of soil selenium, strontium, and magnesium concentrations with Parkinson’s disease mortality rates in the USA[J]. Environ. Geochem. Hlth., 2017, doi:10.1007/s10653-017-9915-8.

[54] Boukhzar L, Hamieh A, Cartier D,etal.. Selenoprotein T exerts an essential oxidoreductase activity that protects dopaminergic neurons in mouse models of Parkinson’s disease[J]. Antioxid. Redox Sign., 2016, 24(11): 557-574.

[56] Wirth E K, Conrad M, Winterer J,etal.. Neuronal selenoprotein expression is required for interneuron development and prevents seizures and neurodegeneration[J]. FASEB J., 2010, 24(3): 844-852.

[57] Seiler A, Schneider M, Förster H,etal.. Glutathione peroxidase 4 senses and translates oxidative stress into 12/15-lipoxygenase dependent-and AIF-mediated cell death[J]. Cell Metab., 2008, 8(3): 237-248.

[58] Vinceti M, Solovyev N, Mandrioli J,etal.. Cerebrospinal fluid of newly diagnosed amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patients exhibits abnormal levels of selenium species including elevated selenite[J]. Neurotoxicology, 2013, 38: 25-32.

[59] Sorolla M A, Reverter-Branchat G, Tamarit J,etal.. Proteomic and oxidative stress analysis in human brain samples of Huntington disease[J]. Free Radical Bio. Med., 2008, 45(5): 667-678.

[60] Sreekala S, Indira M. Impact of co administration of selenium and quinolinic acid in the rat’s brain[J]. Brain Res., 2009, 1281: 101-107.

SelenoproteinsandNeurodegenerativeDiseases

YANG Yujie, LI Nan*

CollegeofLifeScienceandOceanography,ShenzhenUniversity,GuangdongShenzhen518060,China

Selenoprotein refers to a kind of proteins that share the common feature of containing the amino acid, selenocysteine. They participate redox reactions in diverse biological metabolisms through the reductive activity of selenium (Se). The human selenoprotein family contains 25 members, however, for some of them, their precise physiological functions remain unknown. Brain is one of the most Se-abundant tissue, the depletion of some individual selenoproteins by gene knockout results in cognitive impairment and motor dysfunction. A large amount of reactive oxygen species (ROS) could be produced during the metabolisms in brain, and the oxidative stress derived from the ROS is believed to be one of the primary inducements of neurodegenerative disease. Whereas, the clearance of ROS is the prime physiological function of many selenoproteins, therefore the relevance between selenoproteins and neurodegenerative diseases attracts extensive attention these days. Herein, we reviewed the physiological functions of selenoproteins and how they were related to the pathological mechanisms of neurodegenerative diseases, which was expected to provide reference for selenoprotein application in treating neurodegenerative diseases.

selenoprotein; neurodegenerative disease; oxidative stress; Alzheimer’s disease; Parkinson’s disease

2017-07-11;接受日期2017-07-31

深圳市科技项目(JCYJ20160520163119426)资助。

杨玉洁,硕士研究生,研究方向为硒蛋白R在神经系统中的功能。E-mail: yangyujie2016@email.szu.edu.cn。*通信作者:李 楠,讲师,研究方向为硒蛋白在神经系统中的功能。E-mail: lin@szu.edu.cn

10.19586/j.2095-2341.2017.0084