马岩松:新潮的古典主义者

马岩松:新潮的古典主义者

当今的中国建筑圈流行一句话:“建筑师三十多岁是不可能成名的,除非你是马岩松。”自从31岁那年成为中国首个中标海外的建筑师,马岩松便成为了圈内外“年轻有为”的代名词。对于那些拿他和大师作对比的质疑,他不以为然。成为大师,他不着急。

马岩松给鱼建的房子,让金鱼仿佛游入了一个充满趣味的洞穴。

一双淡定的眼睛习惯性地半阖着,配以一口不紧不慢的京腔,马岩松看起来温和儒雅。虽然正值壮年,这个75后建筑师却俨如一位年长的智者。而正是在这样沉静的外表下,成千上万个疯狂而叛逆的想法轮番上演,在他的脑中发生光合反应。

“有时候我在想,如果外星人毁灭地球,他们会留下什么人类建筑。”马岩松冷不丁地冒出这句话,眼神仿似看向无限的宇宙,“也许大部分的建筑都会被摧毁。当我们跳出历史维度看世界,我们也许会发现,现在说的‘古典'和‘现代',其实都只是历史的一个瞬间。”

马岩松的语速很慢,字斟句酌,像一个沉默的话痨。对他来说无关紧要的问题,仿佛可以直接掉出他的耳朵;而关于城市的现在与未来,他却有着说不完的批判与构想:“你别看我这样,其实我很焦虑。每一天,我都看到满眼的问题和丑陋——现在国内千城一面,自然人文遭到破坏,而人类还在很了不起地建‘第一高楼'。如果三十年内我们还不改变,不发展新的思想,依旧在复制西方现代主义的城市,那我们这一代人真的白活了!其实把眼睛闭上,把耳朵捂上也很舒服。但因为我是建筑师,我有责任提出解决方案。”

目前,马岩松的解决方案是从景观山水的角度,创造一个既顾及城市人口密度和功能需求,又能给人归属感的人文城市。他把这个“乌托邦”称为“山水城市”。在这个山水世界里,现代与古典不是割裂的,它将既具有现代生活的便利,又留存东方独有的诗情画意。

回顾过去,马岩松发现,他对这种理想社区的向往,其实在孩童时代便已扎根。小时候在什刹海游泳划船,在富有人情味的胡同里生活的回忆,已经不知不觉地融入了他的作品里。

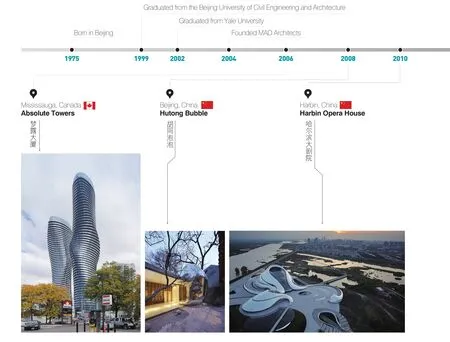

刚从耶鲁毕业的时候,马岩松便开始了对西方摩天楼的批判性反思。他更想设计出一个自然、柔软、拥有人性的楼。三年后,他在加拿大密西沙加市的公开招标中,从来自世界70个国家的600多份竞赛注册和最终的92份提案中胜出,获得了该市最高建筑的方案设计权。

鲜少人知的是,在这之前,创业初始的MAD事务所输了上百次投标和竞赛。可马岩松并不认为自己比其他人更努力。“努力是很正常的,它不能保证结果,而思考和探索才是最关键的。”可以随时随地陷入深度思考的马岩松,把自己定义为一个“不太传统的传统的人”。他认为正是历史中始终贯穿的反叛精神,在不断推动着人类文明发展和演变。

这个在许多人看来已经达到“人生巅峰”的“明星设计师”,其实从未想过转行或是跨界。建筑是他愿意付诸毕生热情和耐心的事业,他清楚实现设想的过程必然是缓慢的,而这正是建筑的魅力所在。

“建筑这行就像个无底洞,让人一直专研却依然会感到遗憾。在充满激情的创作后,等到房子盖出来了,却往往不是你预想的那样,或者这时候你的理念已经产生了变化。你总觉得下一个更好,于是周而复始。”马岩松看似在吐槽,对建筑却是看尽沧桑后的真爱。

在他看来,创造每一个建筑的旅程都是对精神更深层次的探索,而这个长期追求的过程与建筑师的思想成熟度相关。“所以我认为年轻人是不可能成为大师的。最终,谁活得更老,谁就成为大师。”说完,仿佛是为了配合自己的冷幽默,马岩松“嘿嘿”地憨笑起来。

MA YANSONG TALKS ABOUT ORIENTAL PHILOSOPHY OF ARCHITECTURE

N=NIHAO

M=MA YANSONG

N: What's your take on new forms of architecture in today's China?

M: The world in which we live today is fi lled with

realism. We are so much infl uenced by modern values that we are extremely keen on impact and size of architecture, as the Olympic motto, “Faster, Higher, Stronger,” rightly puts it. Yet the core of traditional Chinese wisdom lies in emotional satisfaction deep down in one's heart. For example, traditional Chinese gardens focus on the creation of feelings or emotions one has when they are in them rather than on extremes. This kind of high taste is rarely seen in modern cities, as we talk so much about things like economy, politics and power. But I believe the day when we can talk about architecture as a cultural topic will surely come. I wish that the time-tested wisdom of ancient Oriental civilisation—that it is the journey, not the destination that oneshould enjoy most—would come alive again one day, contributing to the thoughts of the world at large.

N: How is “novel architecture” of the West being accepted in China?

M: The National Centre for Performing Arts, the CCTV Headquarters, and the National Stadium (also known as the Bird's Nest), all based in Beijing, are iconic examples of China opening its doors to architects from around the world. In recent years, all kinds of conservative, strange or even uglylooking cultural buildings have sprung up across the country. Yet we must distinguish between good taste and simple novelty. Why is China so open to international designers? It is because we are not very sure about where our own culture stands. That's why classical and ugly buildings are so awkwardly put together. That's why China is dubbed by some as “a testing ground for foreign architects.” Of course, this is perhaps a step that any culture has to take towards maturity. The fact that China - or any place - gathers the world's fi nest architects at least shows its open attitude toward

new ideas.

N: How far are you from your “Beijing 2050”vision? Why did you come up with this vision in the first place?

M: Thirty-three years, obviously (he smiled when he said this). The city of Beijing has grown too large to cover on foot, unlike its original layout, which largely consisted of today's Jingshan Park, Beihai Park, Gulou (Drum Tower) and Houhai Lake. The spiritof a life amid nature is thus lost. In fact, the new districts of many Chinese cities are all alike, featuring large squares and wide roads. The result is that people have to travel, either on foot or by vehicle, from one place to another, with each area serving a single function, just like a farm. The same is true with the layout of residential apartments, which all look about the same, for architects have designed them without thinking that their occupants would live a life fi lled with emotion.

In fact, the whole of old Beijing was a garden, where human life was inextricably intertwined with nature. At least this was the memory of many older native Beijingers. My hope is that the garden style can survive the changes of our time and beyond, so that our culture will prosper in harmony with nature. A vision, a spirit and value are what we most urgently need to defi ne for the city.

N: Has the West's recognition of Chinese architecture risen in recent years?

M: Following China's reform and opening up, more Chinese architects opened their eyes to the West and began to think about the differences between Eastern and Western cultures. After more than three decades, we are catching up with the West in terms of architectural quality, materials and technology, but we still lag behind in terms of the origination of infl uential thoughts as well as cultural impact globally. But the Western world is indeed starting to pay attention to the Chinese force of architectonic—for example, by publishing Chinese architects' exhibitions.

N: What advice would you give to aspiring young architects?

M: Architecture is a profession that requires much hard work, but more often than not, gives one little sense of achievement. Many architects barely get to design a house until they're 50 or 60. But what makes it matter most is architecture as a journey of self-discovery. I used to advise younger architects to “be yourself.” Yet I found out that many understood this partially. Perhaps those who have a strong character could understand me better, for it takes much more time and effort for people with a weak personality to really know themselves. So I have made my piece of advice more specifi c: young architects need to be clear about who they are, what they want and what makes them unique before they follow their heart and put their enthusiasm and sense of responsibilities into practice.