Beauty in the Flaws

By Ma Weidu

Beauty in the Flaws

By Ma Weidu

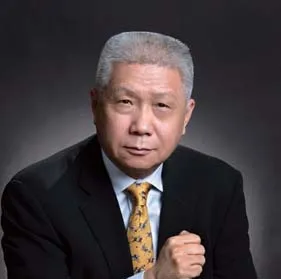

Ma Weidu (1955-), a famous Chinese antique collector, best-selling author and popular talk show host, is the founder and curator of Guanfu Museum, the first private antique museum in China.

In the wintertime twenty years ago, I was invited to dinner at the best beef hot-pot restaurant in Beijing. Twenty guests sat around two round tables. Suddenly, a guest stood up and said he had“something for sale.” He showed us an old album entitledTwenty Pictures of Pottery Making. which depicts the process of pottery making and documented the sintering ceramic products in Qing Dynasty.

During Qianlong’s reign, the emperor was fond of pottery making, so he commanded the court painters to draw pictures ofPottery Making,Farming and Weaving,The Cotton Industry, and many others. The replicas of these valuable pictures were stored in the Palace Museum. None of us had ever seen an original one before.

Now it was before our eyes, one of the original albums, colored and drawn by court painters Ding Guanpeng, Sun You, and Zhou Kun. It was told that Emperor Qianlong had been very satisfied with the paintings and ordered Tang Ying, the official porcelain conservator, to look after it carefully. The album now was in a poor condition, full of water stains.

The owner bade a price of 300,000 yuan. I was eager to take it when a friend pulled my sleeve and told me that anything in such poor condition would lose its value.

“One hundred thousand,” I responded, half hesitating.

The owner gave me a blank glance and left without a word.

In the evening, I called the guy again to ask if he would sell it to me for 150,000 yuan. He refused me.

On May the next year, I saw this album again in Christie’s, Hong Kong. The pictures were repaired well with only light marks of waterlogging. Yuanta ETFs, one of best Ming and Qing porcelain collectors in Taiwan, purchased it at a price of 2,200,000 yuan.

In the 1980s, I heard a true story about a Taiwanese man spending ten thousand dollars on a Xu Beihong’s painting, which was in extremely bad condition. He sent it to the famous antique shop Rongbaozhai and asked for a re-mount. The restorer just spread out the painting on a table, and poured boiling water onto it. Gosh! Burning ten thousand dollars would be slower. But finally the painting was restored perfectly, just a little lighter in color.

I have seen even more magical skills in restoring old furniture. In earlier times, when you found a set of valuable old furniture, you could transport it to a restorer by tricycle. The man would first boil two kettles of water, and then put two cubes of alkalis (often used in steaming mantou at the time) beside the kettles. After the alkalis had melted in the heat, the restorer would pour the hot liquid onto the furniture, and cover it for a while. Then with a brush, the man would clean the surface of the furniture, and repair the damages with glue.

When all above procedures were done, the skilled man would say, “Almost there. Now let’s cleanse it.”

The term “cleansing” in furniture repairing business means scraping off a thin layer using a carpenter’s plane. It was that tiny cleansing plane, moving so fast in the repair man’s hands, with wood shavings flying from its edge like scraps of tissue paper.

Now if you visit Guanfu Museum, you can see a big painter’s red sandalwood table. (With the one-meter diameter of its top, the table is the world’s largest.) Many visitors are curious about the brand-new look of the table. I can tell youit’s all about the “cleansing” work.

The concepts of furniture repairing, or antique restoration, are different in China and abroad. Chinese aim to make old things look new. We use the same kind of materials of the original furniture to repair it, that is, huanghuali wood for repairing huanghuali wood furniture, and rosewood for rosewood, red sandalwood for red sandalwood, and so on. A skilled Chinese restorer can make the damaged parts of the furniture “invisible.”

Westerners tend to leave historical marks as they are. They also use different materials in repairing, to the point that you can see clearly where the mending works have been.

So is the difference between Chinese and Japanese porcelain restorations. I have seen the incredible works of some highly skilled restorers in South China nowadays. Even under high-powered magnifying glass you can hardly find the traces of any damage. A friend of mine once showed me a restored Song dynasty porcelain ware, along with its previous photo in which I could see a crack on the edge. Without that photo I would never have known that it had been damaged. In the past, under a high-powered magnifying glass, you could tell the difference, because inside the repaired area there were no bubbles a sintered ceramic product should have inside. But nowadays they can even “create” the bubbles, arrayed in the same way as the original. Isn’t it amazing?

Japanese people do this work differently. They use lacquer and the mixture of water and mine ashes to mend damaged porcelain ware, and then paste gold foil on the repaired place. Yes, pure gold. The technical term of this step is “goldmending.” This gives Japanese antiques and many historical sites a special beauty.

In old times, there was also such a style of restoration in China. It was called “cramping.” The restorers used juzi, a kind of cramping, to mend things such as woks, bowls, and urns. Broken porcelain ware could be cramped with juzi and be put back in use. Some bowls I saw with juzi on them were really beautiful.

In earlier days, wares with juzi were cheap. At that time I bought some colorful bowls mended with juzi; they were awfully beautiful and cost me only several yuan. In early 1980s, some dealers from abroad purposely looked for these antiques in Beijing markets. The price was offered according to the number of juzi. Ten yuan for one juzi; a bowl with twenty would be worth two hundred yuan. A man who sold his bowl with more than one hundred juzi was said to be made rich.

A former praising term to describe wares with many juzi was the phrase “centipede feet.” By unique great skills, lots of the tiny juzi were arranged in order. Those foreign dealers thought that porcelain wares with juzi had “a beauty of flaws.”We Chinese people didn’t understand that beauty until all such wares were bought and gone.

So what was the concept in this old repairing work? It’s to value your household articles, I think, and not to waste. With this in mind, restorers can go anywhere and earn a living.

(FromDu Du (Volume II), New Star Press. Translation: Wang Xiaoke)