The Half-industrial and Halfagricultural Working Structure in Rural China

Yang Hua*

The Half-industrial and Halfagricultural Working Structure in Rural China

Yang Hua*

The half-industrial and half-agricultural working structure in rural China is a key phenomenon supporting China’s industrialization and urbanization. Based on inter-generational division of labor, the current half-industrial and half-agricultural working structure has given birth to the elderly agriculture and mainstay agriculture, the latter of which has gone out of agricultural involution and to some extent changed the management philosophy of traditional agriculture, becoming a key direction of China’s agricultural development. Such a structure has also shaped the “new three-generation family” and facilitated the expansion of middle-income rural groups. While supporting long-term farmers in rural China, it also paves the way for China’s urbanization. This structure plays a significant role in the economic, political and social development of rural China. Therefore, this structure is a rural economic structure which concerns farmers’ income structure and livelihood patterns. Meanwhile, it is also a rural political structure, village structure and family structure. Through development and refinement, the half-industrial and halfagricultural working structure in rural China has far extended the scope of a descriptive concept. As a dominant variable, the structure, along with its derivatives, through permutation and combination, can establish logical relationships and an interpretation chain among a variety of major economic, political and social phenomena in rural China. Therefore, it can expect to be constructed into an analyticity-oriented mid-level concept.

rural structure; half-industrial and half-agricultural; inter-generational division of labor; new three-generation family; middle-income group

1. Issues raised

During China’s rapid modernization and urbanization, its vast rural areas played the roles of “impounding reservoir” and“stabilizer.” Unlike Western Europe or the other developing countries over the past decades, China’s modernization and urbanization hasn’t been accompanied with such tragedies as “sheep eats up men” or “a large number of farmers are compelled to leave their home.” Besides, there is no such scenario as the drastic decline of rural area or the emergence of large slums across cities. In other words, the urbanization of the West and the other developing countries are invariably accompanied with the decline of rural areas and the end of the farmers’ era. However, China proves to be an exception, which has a lot to do with its series of institutions, policies and social arrangements, such as institutional urban-rural dual structures, collective ownership of rural lands, abolishment of agricultural taxes, the policy of “strengthening agriculture and benefiting farmers,” effective rural grass-roots units and rural community-based construction of a new socialist countryside. Such institutions and social arrangements have reshaped the relationships between the country and its rural society, and also adjusted and improved the relationships between the rural and urban areas. In the meantime, they have been included, internalized and reformed by the rural societies and have been embodied in the halfindustrial and half-agricultural working structure in rural China.

Gradually developing and stabilizing since China’s Reform and Opening-up, this half-industrial and half-agricultural working structure in rural China is based on the collective ownership of rural land, the urban-rural dual structure, as well as the traditional rural family system. This halfindustrial and half-agricultural working structure, primarily relying on inter-generational division of labor at present, brings about an occupational division between generations within a family. More specifically, the younger generation are away from home as migrant workers while the middle-aged and elderly members stay at home for agricultural production. In this way, a family can expect to enjoy two income sources, i.e. industrial income and agricultural income. In fact, the half-industrial and half-agricultural working structure is concerning economy, society, family, as well as politics. The forming and stabilizing of such a structure has exerted a decisive impact on China’s economic development and social stability. For example, it provides an endless cheap labor force to facilitate urbanization and transform rural China into a rear area for eliminating urban crises. Also, it manages to deliver a profound impact on rural China’s economic development and social and political structure.

The existing academic research into the halfindustrial and half-agricultural working structure mainly focuses on agroeconomics, or farmers’income structure (Huang, 2006). Being stable and institutionalized, the half-industrial and halfagricultural working structure is no longer an isolated existence. Instead, it frequently interacts with the other rural economic and social structures in which it is embedded. This paper attempts to conduct a preliminary analysis of the half-industrial and half-agricultural working structure in rural China to unveil its agroeconomical connotation and social and political significance, and tries to interpret and construct it as a mid-level concept.

2. The development, characteristics and connotation of the halfindustrial and half-agricultural working structure in rural China

Rural China falls into two categories. One is theresource and wealth-intensive category, exemplified by coastal and suburb rural areas. These areas have already been integrated into urban areas, with their agricultural land incorporated in the scope of urban development. The majority of farmers, no longer engaging in agricultural production, mainly rely on revenue from industrial work, business, as well as land and house rentals. However, those rural areas only account for 5% of rural China, for which their situation should not be deemed a dominant trend. The other is the agricultural production-reliant category. Featuring a low urbanization rate, this category applies to the vast rural area in central and western China. There, part of the farmers are away from home for full-time or part-time industrial work or trade (hereinafter referred to as industrial work). The rest of the farmers stay at home for agricultural production. That is how the half-industrial and halfagricultural occupational and income structures are developed. Those rural areas account for 95% of rural China and therefore should be deemed its main body. It is fair to say that the half-industrial and halfagricultural working structure widely exists in most rural areas of China.

2.1 The development of the half-industrial and half-agricultural working structure in rural China

The origin of this structure can be traced back to the beginning of the Reform and Opening-up in the early 1980s. Back then, with the introduction of “fixing farm output quotas for each household”policy and the revival of urban markets, some farmers began to engage in other work such as trade and manual processing during the slack season. However, such a structure did not really come into being until the mid to late 1980s. Following that, it experienced two transformations in the mid to late 1990s and the 2000s. Now, this half-industrial and half-agricultural working structure can be subdivided into three categories.

2.1.1 The half-industrial and half-agricultural working structure based on the concept of departing farming without leaving native land

In the mid to late 1980s, township enterprises sprang up like mushrooms across rural China. It was no exaggeration to say that “township enterprises could be found in almost every village and every township.” Such a boom offered a large number of jobs to surplus rural laborers. In this context, finding a job nearby became a trend in rural China. While there were some young adults “leaving farmland for factory,” they departed farming without leaving their native land. Some of them worked at the factory during the daytime and went home in the evening, or they stayed at the factory only during work hours and went home during the meal and breaks. Some farmers did farm work during the busy farming season and worked at the factory during the slack season. Alternatively, they could work at a nearby factory during daytime and did their farm work after returning home. In this way, a sense of “work schedule” was built among farmers. On the other hand, some farmers failed to be recruited by any factory and therefore could do nothing but rely on their farmland. Such a half-industrial and halfagricultural working structure, based on the concept of departing farming without leaving the native land, enabled a rural family to have two income sources, i.e. factory work and farm work and ensured rural family unity and soundness of rural political and social life. With a large number of young adults staying in the rural area, there was no problem in handling village-level public affairs and holding public events. In other words, villages still enjoyed a relatively sound and complete public space. In fact, such a half-industrial and half-agricultural working structure was especially popular in coastal developed regions.

2.1.2 Gender specific labor division based halfindustrial and half-agricultural working structures

In the 1990s, cities gradually lifted their restrictions on the rural labor force, and a large number of rural migrant workers left home for industrial work in cities. As time went by, in the mid to late 1990s, many township enterprises declined or even closed, forcing farmers to swarm into cities. Farmers left home for industrial work in cities in the 1990s were typical first-generation migrant workers. That generation mainly comprised young male adults, along with a small number of rural single women①Female migrant workers were not approved in many rural areas until the 1990s.. Married rural women stayed at home for agricultural production with their middleaged and elderly family members. That is halfindustrial and half-agricultural working structure based on inter-generational division of labor. In such a structure male farmers, young adults, went to the cities for industrial work while female farmers, also young adults, stayed home to do farm work and look after their families; middle-aged and elderly family members helped with some housework. As abovementioned, such inter-generational division of labor enabled a rural family to enjoy two income sources. As women stayed at home to look after the elderly and the young, there was as yet no such terms as “left-behind seniors” or “left-behind children.” But such inter-generational division of labor also had negative effects on rural China. First, with large numbers of young male adults leaving for the cities, the feminization of agriculture was on the rise, creating a heavy burden for the rural women. Second, young rural couples were forced to lead an incomplete family life, an abnormal sex life in particular. Last, living under the same roof was likely to trigger various family disputes between rural women and their middle-aged and elderly family members.

2.1.3 Half-industrial and half-agricultural working structure based on inter-generational division of labor

Entering the 21st century, particularly since the abolishment of agricultural taxes in 2006, the rural labor force has been further liberated. The barriers between urban and rural areas have been greatly reduced and rural customs have been significantly changed. It is no longer an embarrassment for young female adults to leave home for industrial work. Thus, it has become a norm for all rural adults at a proper age to leave home as migrant workers. In such a context, China has witnessed an unprecedented migration movement with a total of 250 million migrant workers traveling between hometown and cities per year. During this period, there was also an apparent change in the division of labor within the rural family. Young rural adults, whether married or not, leave home as migrant workers for higher pay. Middle-aged and elderly farmers stay at home, continuing their farm work to gain agricultural benefits. Thus, the half-industrial and half-agricultural working structure based on inter-generational division of labor has gradually developed. This division of labor has its own merits. First, it helps to increase the income of migrant workers and has substantially improved the living standards of rural families. Second, working at the same place enables young rural couples to have a regular family life. Yet, such a division of labor is not without problems. The absence of young couples at home leaves their aged parents and kids uncared for, thus giving rise to the issues of “left-behind seniors”and “left-behind children.” Left-behind seniors are likely to feel empty and lonely and may not be able to find anyone for help when they are sick. This is a key factor for the increased suicide attempts made by rural seniors in recent years (Yang & Fan, 2009).

2.2 Major characteristics of the halfindustrial and half-agricultural workingstructure in rural China

The half-industrial and half-agricultural working structure in rural China has experienced three decades of development. Through shifts and adjustments, it has managed to develop into halfindustrial and half-agricultural working structure based on inter-generational division of labor. The characteristics of this structure in rural China can be summarized in the following three points.

2.2.1 Long–term phenomenon

The half-industrial and half-agricultural working structure in rural China is generally accepted as a compelling management system. The excessively intensive agricultural system, featuring a large agricultural population and limited arable land, cannot generate satisfactory returns, forcing many farmers to leave home for industrial work. On the other hand, the risks of being migrant workers in turn force those farmers to rely on agricultural production to hedge such risks. For Chinese farmers, this is indeed a compelling choice, which is frequently criticized for being a negative outcome of China’s institutional and policy arrangements, particularly the longstanding institutional urbanrural dual structure. To tackle such a compelling issue, China should break through the barriers of this urban-rural dual structure, particularly the household registration system so that migrant workers can live and work in cities freely and enjoy equal social welfare there. The abovementioned criticism has overlooked the objective basis for the long-term existence of the half-industrial and halfagricultural working structure in rural China. This objective basis refers to the social environment which cannot promise migrant workers a decent urban life even if they are offered free access to cities. Currently, China has some 700 million farmers in rural areas and over 200 million migrant workers in urban areas. Given the average salary of migrant workers and current urban living standards, less than 10% of migrant workers have the chance to settle down in a city and lead a decent life. The 90% majority cannot expect to establish themselves in cities and therefore have to continue with their halfindustrial and half-agricultural way of life. Most of the Chinese industries remain at the low end of the global value chain and are in the labor-intensive processing category. There is not much left when the already low profit is further distributed to migrant workers. That is why their wage level has remained fairly low for such a long time. One must realize that urbanization in China is inevitably a longterm and gradual process, during which only truly capable migrant workers have the chance to settle down in cities, while the majority have to shuttle between urban and rural area. This reality also means that the half-industrial and half-agricultural working structure, covering 700 million farmers in rural China and 200 million migrant workers in urban China, is a long-term structure. The halfindustrial and half-agricultural working structure is not a temporary phenomenon, and it will remain unchanged in future decades, exerting a significant impact on the rural economy, politics and society.

2.2.2 Stability

At present, half-industrial and half-agricultural working structure based on inter-generational division of labor is conditioned by a reshuffle of the division of labor within a rural family. Through such a reshuffle, this working structure is gradually consolidated and stabilized. For farmers, agricultural work generates less income than industrial work. Even so, some farmers must stay at home for agricultural work to ensure their basic needs. From another perspective, what factories in urban area really need are young adults who can respond quickly, rather than aged adults. Under such circumstances, migrant workers beyond a certain age are forced to withdraw from the assembly line. In general, for assembly line work, migrantworkers, regardless of gender, gradually lose their competitiveness once reaching 35 and are likely to be replaced by their younger peers. Most migrant workers over 40 can only expect to find a job at a construction site or in the service sector. Migrant workers over 50 are unlikely to find employed in any urban sector. When it comes to the division of labor within a family, it is more than for a young couple to (be required to) choose work at an assembly line for higher pay, and for middle-aged and elderly family members (who are refused by such an assembly line) to engage in agricultural production, which generates less revenue. Such inter-genational division of labor within a family will remain stable in the long term and form a steady structure.

2.2.3 Reproducibility

The current gender division of labor based halfindustrial and half-agricultural working structure is reproductive. This is a prerequisite for its longterm stable existence, with an endless supply of labor to support this working structure. As a young couple grow older, they will no longer be suitable for assembly line work and will subsequently be replaced by younger migrant workers. When they eventually withdraw from their urban work, they will return home to take over the agricultural work from their elders. By then, it will be their grownup children’s turn to go into the cities for industrial work. In this way, the division of labor within a family (i.e. a young couple for assembly line work and middle aged and elderly family members for agricultural work) is repeated in endless cycles. This is the reproducibility of the half-industrial and half-agricultural working structure based on gender division of labor.

The long–term existence, stability and reproducibility of the half-industrial and halfagricultural working structure in rural China will also be embodied in its subordinate rural structures, institutions and phenomena.

2.3 The basic connotation of the halfindustrial and half-agricultural working structure in rural China

The current half-industrial and half-agricultural working structure in rural China is a general structure, not just an agricultural management system or a rural family income structure, but also a social institution (Xia, 2014). The half-industrial and half-agricultural working structure in rural China bears the respective connotations of rural economic structure, social structure and political structure. This working structure shapes and reconstructs a new economic structure, social structure and political structure for rural China.

2.3.1 Economic structure

First, the economic structure concerns the rural income structure. The half-industrial and halfagricultural working structure means a rural family has two income sources. One is industrial work, which contributes 60%–70% of the total family income. The other is agricultural work, which contributes about 30%–40%. For a rural family, the two income sources are indispensable, for they ensure their survival and labor force reproduction. Those elderly family members may stop doing agricultural work and only look after their grandchildren, or just lead an easy life at home. Even so, they can still save significant expenses for their family. According to such an income structure, even with an industrial income source, a rural family still must rely on agricultural income. To this end, the existing rural land system must remain unchanged in the long term. It can conduct land transfers but large-scale land transfers with deliberate intention are prohibited, for it enables capital to drive farmers away from their land and results in the loss of their agricultural income. Second, the economic structure concerns the agricultural management system. The half-industrial and half-agricultural working structure determines the managing subjects of ruralland to be middle-aged and elderly farmers, and some young adults. Through a family management model, farmers maintain their management scale at“1.3 mu per capita with a maximum of 10 mu per household.” This new management model has both similarities and differences with traditional “small peasant private ownership,” and it is not the same as the capitalist model of farm management (Yu & Liu, 2013). Third, the economic structure also concerns the occupational structure of farmers. In the vast rural areas of central and western China, some 70% of families’ occupational division of labor is based on the half-industrial and half-agricultural working structure. That is to say, half-industrial and halfagricultural families account for 70% of all rural households there. This cannot give rise to much occupational differentiation, which means there is no big income gap among these farmers.

2.3.2 Social structure

Social structure includes village structure and family structure. First, the half-industrial and halfagricultural working structure requires some farmers to leave home as migrant workers and the rest to stay at home for agricultural production. The two groups keep in close touch with each other. Moreover, most migrant workers are expected to return to their village sooner or later. In this sense, villages remain the farmers’ final destination and still have the capacities of value creation and social discipline. Some 70% of rural families are within the halfindustrial and half-agricultural working framework. There is no significant income gap among them and they fall into the middle-income group in rural China. (Chen, 2014). The limited economic differentiation among farmers indicates the existence of a vast middle-income group in rural China. This group is of vital importance to rural social stability and can prevent apparent social stratification there. Family structure refers to the fact that the half-industrial and half-agricultural working structure is a labor division structure of the rural family, which forms stable and fixed inter-generational division of labor and at the same time forges a new family form, i.e. the“new three-generation family.” Such a new family form is nothing like traditional big families (such as combined family and lineal family) or a Westernstyle core family. In this new family form, the young couple, being away from home for industrial work, still maintains a united family with their parents, who are responsible for housekeeping, taking care of the young, and saving money. Even so, the young couple and their parents are independent from each other when it comes to money management.

2.3.3 Political structure

To some extent, the half-industrial and halfagricultural working structure can cause outflow of both talents and wealth from the rural areas. It is worth mentioning that young and vigorous farmers capable of finding a job in town have all left, leaving the old, the weak, the pregnant, the young, as well as the disable at home. Under such circumstances, a new problem arises. Who should take charge of rural governance? This is a question that must be answered. Due to the halfindustrial and half-agricultural working structure, a significant number of farmers are away from home for industrial work, leaving some farmland unused. Through spontaneous transfer of such unused land within a village, more and more land is obtained by a small group of farmers. Those people mainly rely on farmland to gain profits and focus on enhancing interpersonal relationships within their village. Caring about farmland-related interests and village-based social relationships, they are willing to participate in village governance and build relationships. Given that, this group of farmers have the potential to take charge of village governance and play a crucial role in rural political life. Neither very rich nor very poor, those farmers are of a middle-income group in the villages. The half-industrial and half-agricultural working structure rules out the possibility of rich farmers dominating rural governance in the vast rural areas of central and western China.

3. The agricultural economic significance of the half-industrial and half-agricultural working structure in rural China

Over the past decades, China has witnessed tremendous changes in agricultural management. Also, attempts have been made to tackle agricultural involution. In Huang Zongzhi’s term (2010), such a reform is called “China’s hidden agricultural revolution.” From a microscopic perspective, the differentiation in village-level agricultural managing subjects is the direct factor that triggers revolutionary changes in Chinese agriculture. The characteristics and capacities of these agricultural managing subjects determine the amount of investment into agricultural management, corresponding labor relations, agricultural type, management models, etc. and subsequently determine the development direction and strategy of Chinese agriculture. The half-industrial and half-agricultural working structure divides farmers into farmers for industrial production and farmers for agricultural production. The latter forms the principal part of agricultural management and can be subdivided into the middle-aged and elderly groups and the mainstay group. Their agricultural production activities are respectively called the “elderly agriculture” and the mainstay agriculture,” which are both interconnected and different from each other.

3.1 The “elderly agriculture” in the halfindustrial and half-agricultural working structure

As its name suggests, elderly agriculture refers to an agricultural model which mainly relies on the engagement of middle-aged and elderly farmers. According to the inter-generational division of labor in rural China, middle-aged and elderly farmers, due to their declining physical capacity, are left home for agricultural production. Most of them fall into the age group of 50─65. They are responsible for their family’s contracted farmland, which usually covers an area of 1─20 mu. Farmland larger than 20 mu is beyond their physical ability. A higher level of agricultural mechanization makes it possible for farmers to leave some heavy and tedious manual work to mechanical equipment. Thanks to that, farmers over the age of 70 can still do some farm work. Their agricultural production is of a self-employed nature and is performed based on a family unit. Usually, it involves a middle-aged or elderly couple and some auxiliary manpower. Labor employment seldom happens and as mentioned above, some manual work can be left to mechanical equipment. During the busy farming season, a few relatives and friends may come and help, which is either a pure favor or a mutual help. The purpose of their agricultural production is to realize self-sufficiency and support their family, rather than facilitate market exchange. Only extra farm production is used for market exchange, which becomes an income source for elderly agriculture’s simple reproduction.

Basically, elderly agriculture can be regarded as a diversified agriculture. That is because those still capable middle-aged and elderly farmers not just do farm work, but also do some part-time work or other small businesses nearby during the slack season. Considering the opportunity cost of this diversified agriculture, elderly agriculture, though still of an intensive farming type, is far behind traditional agriculture in the degree of intensive and meticulous cultivation. In terms of per mu yield, elderly agriculture cannot compare with mainstay agriculture, but is higher than investment supportedagriculture (Yang, 2013). When reaching 60, farmers can find fewer part-time jobs and elderly agriculture is transformed into leisure agriculture. As physical demands and labor intensity keep reducing in agricultural production, the importance of management and protection is highlighted. Whenever they like, the elderly can stroll around their field, loosening clay soil, weeding, applying fertilizer, and catching insects. While killing time and enriching their life, they also keep health through such fieldwork. Thus, what elderly agriculture values is not average profit, but growth in per unit area yield. If their physical condition allows, the elderly can engage in agricultural production as they wish. Elderly agriculture enables elderly farmers to earn their own living without being at the mercy of their children or children-inlaw. This helps to avoid many conflicts between the two generations. Elderly agriculture remains an indispensable income source of a rural young couple’s family. To a large extent, it eases the family burden on the younger generation.

3.2 The “mainstay agriculture” in the half-industrial and half-agricultural working structure

The half-industrial and half-agricultural working structure means most young male adults are away from their village, leaving part of the farmland in the charge of the middle-aged and elderly farmers and the rest to the young and middle-aged farmers who choose or who are forced to stay in the village. Moreover, as the middle-aged and elderly farmers grow even older, they gradually withdraw from agricultural production, transferring their farmland to those young and middle-aged farmers capable of managing more farmland. Young and middle-aged farmers refer to farmers falling into the age group of 30─50. They are arguably the most physically capable group in rural China. They are mainly in charge of two types of farmland. One is their own contracted land and the other is the contracted land of other villagers who are away from home for industrial work. Each of them can manage a combined area of 20–40 mu. For the most capable among them, the management capacity can reach up to 100 mu. The extra farmland is mainly transferred from relatives and friends, for which no rent or very little rent is required. Besides, there is no need to sign a transfer agreement. When the owner of the entrusted land plans to return home, and resume their agricultural trade, he or she only needs to inform the entrusted farmer half a year in advance.

In terms of cultivation scale, mainstay agriculture ranks between elderly agriculture and investment-supported agriculture. Its managing subject can be called “mainstay farmer.” Mainstay agriculture is of a family farm-based cultivation pattern. Normally, a young couple, assisted by a tractor and other machinery and some hired labor in the busy farming season, can manage a total of 100 mu of farmland. Mid-level agriculture can generate a higher yield than elderly agriculture and investment supported agriculture. Mainstay agriculture combines self-employment with labor employment and is performed on a family unit basis.

Mainstay agriculture is different from elderly agriculture in terms of management scale and model. Elderly agriculture falls into the substance agriculture category. With its agricultural production linked to consumption, it pursues yields, rather than profits. By contrast, mainstay agriculture aims to bring its agricultural products to market, for which its agricultural production is market-oriented. Thus, it can be concluded that mainstay agriculture is a commercial agricultural model which focuses on seeking profits and at the same time gives consideration to meeting the farmers’ own needs. While striving to increase its per unit area yield, mainstay agriculture also begins to raise averageprofits. As we know, when the per unit area input of its factors such capital, labor force and technology generates the maxim yield, there is bound to be a progressive marginal benefit decrease. In that case, the managing subject no longer invests in farmland and begins to shift their investment interests to other sectors. That explains why the average scale of midscale agriculture restricts its farmland area within 100 mu. After all, once its scale exceeds 100 mu, the increased input of cultivation factors can bring about a decline (rather than a rise) in its average profit. Therefore, no more farmland or cultivation factors are to be added.

As a commercial agricultural model, mainstay agriculture can maintain its managing subject’s passion for the use of improved varieties and the improvement of production mode on condition that the marginal benefit is above zero. Also, by sticking to intensive and meticulous cultivation, mainstay agriculture can expect higher yields and higher profits. For a young rural couple managing 40─100 mu farm land for two seasons, they can generate annual revenue of some 80,000 yuan to 200,000 yuan. Such annual revenue is at a high level in rural China.

Mainstay agriculture and elderly agriculture are interchangeable. When the practitioners of mainstay agriculture enter the elderly group, they cannot afford to manage mid-scale farmland any more, and have to gradually render part of their farmland, thus transforming their management into elderly agriculture. Their returned land is then transferred to other farmers and is expanded into a mid-scale agricultural business, thus becoming part of a mainstay agriculture operation. This is how mainstay agriculture’s withdrawal mechanism and reproduction mechanism work.

3.3 Comparison between elderly agriculture and mainstay agriculture

There are both similarities and differences between elderly agriculture and mainstay agriculture (see Table 1). Elderly agriculture still maintains a traditional small-scale farming system, while mainstay agriculture is on its way to modern agriculture.

According to relevant research, elderly agriculture falls into the category of traditional labor-intensive agriculture and is not primarily profit oriented. Even so, its very existence is still a necessity. Given that the half-industrial and halfagricultural working structure will exist in the long term and that the differentiation of farmers remains far from thorough, the middle-aged and elderly farmers cannot separate themselves from agricultural production. Therefore, their family should enjoy a certain agricultural surplus. Both in terms of production efficiency and per unit area yield, mainstay agriculture performs best of all. Mainstay agriculture features mid-scale farmland and corresponding investments of labor, capital and other factors. To some extent, it still belongsto the labor-intensive agriculture category, but it is also of a capital and technology-intensive one. Mainstay agriculture pursues average profits and is now at least half way to getting out of agricultural involution. In this sense, it is different from traditional small-scale agriculture. Thus, it can be concluded that the development motive of Chinese agricultural production originates from the (notthorough-enough) differentiation of agricultural managing subjects, whose managing purposes, efficiency and mode are determined by their own characteristics and natural endowments. Mainstay agriculture indicates a future direction for China’s agricultural transition and development. Therefore, China should encourage and support the transfer of surplus farmland to the managing subjects of minstay agriculture, and at the same time acknowledge the rationality of elderly agriculture’s long-term existence.

4. The political and social significance of the half-industrial and halfagricultural structure in rural China

As an operation model, the half-industrial and half-agricultural structure pattern’s political and social significance to rural areas even outweigh its implications on agricultural operations. Its comprehensive and systemic implications to rural politics and societies are many.

4.1 Shaping “new three-generation families”in rural China

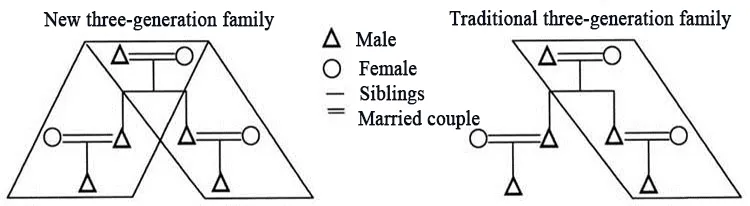

The traditional Chinese family patterns in rural areas are categorized into joint families, stem families, and nuclear families. Among them, the nuclear families make up the biggest share, followed by stem and joint families. The term “joint family” refers to any family composed of two or more couples from any generation. For instance, a family composed of parents, their children, and the children’s spouses and offspring, or a family composed of siblings and their spouses who still live in the same residence after marriage can be identified as a joint family. As the result of lateral expansion of nuclear families of the same generations, a joint family is characterized by big family size and complicated relationships. However, its family members usually are not closely related to each other as each basic triangle has its own center. Therefore, joint families only happen under specific circumstances, which are relatively rare today. A nuclear family refers to any family composed of two generations, parents and their unmarried children. As the principal pattern of traditional families in China, nuclear families are becoming more common in modern China. A stem, or lineal, family refers to any family composed of the parents and one married child or their unmarried children. The stem families are equivalent to the “three generation families,” usually including grandparents, parents, and unmarried children. There are two patterns of stem families, depending on the son, whom the parents live with─some parents would live with the family of one of their sons (mostly the youngest one) after the other sons have moved out, while some would live with the family of their only son. The three-generation families made up roughly 30% of the traditional Chinese family patterns, with no remarkable changes in percentage until the 1980s when the share of nuclear families increased dramatically. With more and more youngest and only sons moving out of their parents’ houses, the share of “three-generation families” declined to 24.29% in 1982.

It is a common view in the world’s industrialization processes and sociological theories that, along with industrialization, urbanization and the development of modern economies the midscale agricultural economies with families as their major units will be replaced by individual industrialworkers, and the traditional rural family patterns by nuclear families. However, the resilience of the three-generation family pattern is well argued in the research related to the history of economy and law by Huang Zongzhi (Huang, 2013). By leveraging the findings of Huang in the historic data and literature, I have further identified a new finding: The share of a new family pattern─or the “new three-generation families” defined in this article─which has emerged along with the half-industrial and half-agricultural structure in rural China has far outweighed the traditional “three-generation families” in statistical terms.

The traditional three-generation families are defined by parents who live with the family of one of their sons after the others have moved out or if they live with their only son. To this end, such a family pattern is of statistical significance only when the households of the gray hair are registered in the families of their offspring. Since 2000, the half-industrial and half-agricultural family structure, which is based on inter-generational work divisions, has emerged in rural China, with the young couples going out as migrant workers, and their children usually left behind and attended by their farming parents at home. The grandparents will have to take care of all their sons’ families and children. In such cases, the young couples normally are not separated from their parents in the terms of family lands, properties, and social relations.①The survey in central China shows that the “division of relatives”custom is still preserved in many villages, namely the duties of the parents family to visit their relatives and friends are shared among the individual children’s families..In the meantime, the outgoing migrant couples have formed individual small families who are independent financial units. To this end, the old parents remain connected separately to each small family of their sons. However, a small family in such a family is independent from the families of their siblings. In this sense, such a family is different from a traditional “three-generation family” in which parents will live with one of their sons when their other children have moved out. The small families in such a family pattern are all independent nuclear families, therefore not as closely related to each other as the ones in a traditional three-generation family (see Figure 1). In light of this, “new three-generation families” make up roughly 80% of the families in rural China.

Figure 1 The “new three-generation families”and the traditional “three-generation families”

The “new three generation families” has the following features:

(1) The “new three-generation families” are a result of the “half-industrial and half-agricultural structure” family structure based on intergenerational work divisions. The structure of the“new three-generation families” is sustainable, stable, and reproducible. Therefore, it is likely to remain the dominant rural family structure for the next several decades.

(2) With its roots in the half-industrial and halfagricultural structure, the new three-generation family is an inevitably incomplete family pattern half of the family members are living in the countryside, while the other half are constantly working in the cities. It is this half-industrial and half-agricultural structure that has led to the incompleteness in both the lives and relationships of family members. The incompleteness is not onlythe implication of such a family pattern, but also its essential and natural property–the work divisions and geographical separation between the old and the young couples are the very causes of the “inseparable family separations.”

(3) Technically, each small family of the children’s generation would form a “new threegeneration family” with their parents. This is different from the traditional three-generation family composed of the parents and only one son. Additionally, a small family of the children’s generation is independent from their siblings both in formas and social relationships.

(4) The new three-generation family is a kind of inseparable family separation in financial terms. They are de facto “separated” from the parents in financial unit terms, while neither asset division nor ceremonial “family division” has taken place. In this sense, the parents’ and the children’s families are financially independent.

(5) The duties of supporting their parents are shared among all the children’s families, while the parents are obliged to attend, nurture and support the children’s families─a pattern different from the traditional three-generation family, in which the parents only shoulder the duties and responsibilities to the son’s family with whom they are living together, while assuming less obligations to the ones that have moved out.

(6) With the value of “passing the merits and fine traditions to the younger generations,” the parents in a new three-generation family are closely related to each offspring’s family. The parents would make selfless contributions to and place great expectations on their children’s families.

(7) Being highly flexible and adaptable in the division of labor, the new three-generation families can change their divisions according to various tasks and life pressures at different times. For instance, to get through the hard times, they will increase the number of migrant workers by reducing the farming members and transferring part of their lands, thus increasing the incomes of the family. Likewise, they will reclaim or buy some lands, have more members return to the farms, and reduce the migrant members (by asking the middle and old aged male members to stop their industrial works or do parttime jobs) when the burdens have been lifted after the completion of crucial life tasks.

Given these features, the comprehensive and sustainable presence of the new three-generation families have posed new implications and changes on the social and economic lives in rural China. (1) The concerted efforts by the children’s and parents’ families have made the children’s families more resilient to the risks inherent in the process of urbanization and the rural social competitions, helping the children’s families accomplish their life and reproduction of labor powers at a “lower cost”─they will be enabled to either support their families in the cities, or lead a decent life in the countryside. (2) The new three generation family pattern mainly aims at facilitating the migrant worker couples who are faced with social competitions in the cities, instead of focusing on the social lives of their parents at home. Therefore, the rights and welfare of the old are easily neglected, resulting in the de facto “exploitation” of the parents by each child’s family. (3) As the parents are included in different new three-generation families of their children, they will need to be mindful of the well-being of all the small families, which can be overwhelming because of the mental stress from the burdens of the children. They will be more mentally stressed once they are disabled from work as a result of sickness. (4) A new three-generation family is naturally an incomplete family. Therefore, it inevitably results in many social issues, such as left-behind old and children. In such cases, the old are probably unattended when they get sick orlose mobility, some will even suffer from mental loneliness.

The new three-generation families are units of strong resilience to competitions and risks which would transfer many pressures resulting from migrant couples and socialized competitions to their parents, with the rights and welfare of the latter being less focused and guaranteed than they are deserved. The disadvantages of the new threegeneration families include; the parental thoughts to reduce the burdens of their adult children, young children being left behind, elders left unattended, the sense of loneliness, among others (Yang & Ouyang, 2013). These have become the major causes of the suicides of many rural old citizens in recent years.

4.2 Developing a huge middle-income group

The first wave of rich farmers accounted for approximately 5% of all farmers in the vast rural areas in central and western China. After building their family’s fortunes by starting businesses or engaging in trades, these farmers usually relocated their families to urban areas. Another 15% included the poor and the weak─including those with labor deficits (mostly the elderly, weak, sick, disabled, and the infants), the overburdened (who need to support both the seniors and the juveniles), and the people lacking land. This is the group that is unable to obtain salary by going out as migrant workers, nor can they earn extra by planting more farms. Another 10% of rural households are made up of those operating “mainstay agriculture.” The remaining 70% are half-industrial and half-agricultural families who are gaining incomes from both sectors. By adding to the incomes and reducing expenditures, the half-industrial and half-agricultural income structure is enabling the farmers to have a decent surplus.

Industrial incomes account for 60%─70% of the total incomes of a half-industrial and halfagricultural family. The so-called industrial incomes here include incomes earned by working in factories, construction sites, trading in the towns, and making handcrafts. Most of the farmers are inclined to working in factories and construction sites. Statistics show that a typical young or middle-aged couple can send home 15,000 yuan to 30,000 yuan of yearly net incomes. Although couples going out together usually result in higher costs in renting and daily expenses, the couple will still have 20,000 yuan to 30,000 yuan in their pockets when they come home at the end of the year as long as they refrain from some unrealistic urban consumer goods and life styles. However, they might end up with 15,000 yuan. It is possible for most of them to come home with around 20,000 yuan.

The incomes of the elderly might vary markedly with their age and the amount of land they control. Typically, a senior farmer aged between 50 to 65 is capable of tilling 10 mu of arable lands, making roughly 10,000 yuan net income per year; while he will have to reduce the lands once he is over 65 as he will have neither the strength nor the energy for the same amount of work, this senior farmer will still make something between 3,000 yuan to 4,000 yuan each year until he reaches 70, after that he will only plant some vegetables and fruits on a small parcel of land. He can always choose to raise some livestock and poultry as part-time jobs, with which he will exchange for some monetary incomes. All in all, it is quite feasible for such a senior farmer to make 5,000 yuan to 15,000 yuan per year from agriculture.

With their industrial and agricultural incomes combined, a new three-generation family usually get their yearly income somewhere around 30,000 yuan, which would make them one of the middle-income families in rural China. Apart from the incomes, the half-industrial and half-agricultural structure also contributes to a huge amount of savings in four aspects. First, instead of pursuing urban residency, most of the young migrant couples are striving fora decent life at home. Therefore, they will not adopt urban lifestyles in a real sense, nor will they indulge themselves in the conspicuous consumption like the urban middle class often do. Rather, they will save most of their incomes for consumption at home, where they can buy goods at relatively low prices. By doing so, a considerable amount of savings is achieved. Second, the elderly and children in halfindustrial and half-agricultural families usually live in rural areas. it is a cost-effective way for these families to support the elderly while they are alive and give a proper funeral after they pass away and reproduce the labor force─a large amount of family expenditures is saved. Third, with the elderly farming at home, a good number of expenditures are not in monetary form, including grain, vegetables, fruits, fish, and meats─all the sources of protein, fiber, and energy are planted by the old, instead of buying them with cash. For sure that the monetary expenditures will increase should they need to obtain these in cities; Fourth, all the recreation, entertainment and social activities for both the old and the juveniles are conducted within their villages, meaning their consumption activities incurs no expenditures. It is tempting to say that all these nonmonetary benefits are amounting to the invisible welfare of farmers.

The half-industrial and half-agricultural income structure and division of labor not only help such a family earn more and spend less, but also maintain their overall nutrition intake and welfare consumption. The half-industrial and halfagricultural structure is making a farmer’s family one of the households of middle-income and living standards. Combining the other 10% or so “mid-scale agriculture” farmers, there are surprisingly 80% of rural families in the vast central and western China that are above the bar of middle-incomes. That is a significant social phenomenon which will absolutely have its implications on the political and social lives of rural China and which cannot be underestimated.

4.2.1 Acting as a social stabilizer in rural China

Normally, China’s urbanization and modernization echo with the out-flux of labor forces, incomes, and resources from the rural areas. Nonetheless, a huge group of middle-income rural families has emerged, thanks to the half-industrial and half-agricultural structure. That explains why the process has not led to declining and unstable rural areas. Despite the notable gap between the middle-incomes in rural area and the middle or high-income groups in the urban areas, the former will never put themselves in the same coordinate system with the latter in terms of their incomes and consumption. Instead, they still compare and compete with their counterparts at home. The clear majority of rural families would engage in the social competitions within their own villages─namely, getting over the bar of middle-incomes will help them win acknowledgment and approval of others, preventing them from being isolated for being too poor. Even those in underprivileged conditions for the time being would not give up the hope of prosperity as the bar of middle-income is not something unreachable. On the other hand, the middle-income level is more than sufficient to guarantee a decent life, or even a “high welfare life with low expenditures” at home (He, 2007). By winning others’ approvals and living decent lives with dignity, most of the rural residents would feel satisfied with their lives. Additionally, the vast amount of rural middle-income families approve China’s overall political and social environments and its policies, thanks to the merits provided by the urban-rural dual structure, the half-industrial and half-agricultural structure, and the national policies to strengthen agriculture and benefit farmers. With conservative mentalities, they would rather maintain such half-industrial and half-agricultural life style than make efforts to change it. It is these mentalities,their satisfaction and approval with the Communist Party of China and the Chinese government that are acting as the stabilizers of rural societies. A survey I made indicates that most of the farmers are not happy and are concerned with the aggressive urbanization policies and massive farmland transfers by local governments that are forcing farmers to relocate into cities, meaning they can no longer plant on the farmlands. The massive farmland transfers driven by local governments have both facilitated capital in rural China and throttled the small-scale farming economies, forcing the half-industrial and half-agricultural families to give up their farmlands. The two policies have deprived the rural families of both the explicit incomes and implicit welfare of“agriculture.” As a result, their family incomes are decreasing and pure monetary spending is rising, meaning declining living standards and welfare of the family. All these policies are destabilizing the“stabilizers” in rural societies.

4.2.2 Playing their roles in the “de-stratification”of rural societies

While differentiation among farmers is witnessed by the vast rural societies in central and western China, they are not seeing distinguishable social stratum, let along isolation, repulsion, and hatred between different stratums. That can be explained by the de-stratification mechanism which is present in the region. Specifically, the presence of a huge group of middle-incomes generated by the half-industrial and half-agricultural income structure has laid the economic foundation of this de-stratification mechanism. While the income levels of most rural households are worse off than some, they are also better off than many. The consistent incomes will mirror with the similarity and convergence among farmers in many aspects, such as their rights, social relations, consumption patterns, religious beliefs, and values. Moreover, the living and consumption standards of the majority of middle-income families will constitute a reference system, which, to the underprivileged 15% of households in the same village, is not too challenging to reach─after all, they will be isolated and left out should they fail to reach that bar, meaning they will become the “lower class” in real terms. In the light of this, the likelihood of the farmers in a same village being divided into various stratums of different ideas and subjective identifications is low─the village will remain a community of shared relations and ethics.

4.3 The mainstay farmers in rural China

Hardcore farmers refer to the group of farmers who cultivate a moderate scale of farmland by acquiring their farmlands against the half-industrial and half-agricultural structure, or those who are operating “mainstay agriculture” (He, 2004). The share of mainstay farmers varies in different rural regions, ranging from 5% in some mountain villages, to 10%–15% in the Jianghan Plain. Most of the rural regions have a share of mainstay farmers around 10%. Despite their small proportions, the group’s roles and implications in the rural political and social lives should not be underestimated. The roles played by the mainstay farmers are closely related to their social natures and positions in structures of the rural society (Yang, 2013). Apart from the cultivators of a moderate scale of farmlands, and the middleincomes in the village, the group of mid-level farmers also feature the following aspects.

(1) Their interest is closely bound to the farmlands, and their social relationships are in the village. Mainstay farmers are committed to agriculture since they are cultivating farmlands of moderate scales. While they might engage in some part-time jobs nearby during slack farming seasons, the bulk of their incomes are made from the lands they cultivate. Given the scale of economic outputs delivered by the lands, it is less desirable for them to become migrant workers. Thus, their social relationships will be bound to the villages.With their core interest closely bound to the land, mainstay farmers usually engage more actively and energetically in the construction of rural infrastructure. Likewise, with their major social relationships bound to the village, they are the main activists in the community and the main builders of social relations. Compared with migrant workers, the mainstay farmers better understand the diverse needs and concerns of villagers as they are more acquainted with the villages and the households.

(2) They have established harmonious relationships with all the groups in the villages. First, the mainstay farmer gains access to the lands transferred by other villagers as they have earned the villagers’ friendship and trust in their capabilities of having the lands well-cultivated, and in their credibility that the lands will be returned when required. Second, migrant workers usually take the initiative to forge friendships with the mainstay farmers, who are staying in the villages throughout the year, and who would reach out to their leftbehind old and children in need. Third, the mainstay farmers would take advantage of their ample slack farming time to make acquaintance and socialize with all the groups and households in the villages. The mainstay farmers gain authority and prestige as they actively take advantage of their ample slack time to solve problems and relieve concerns for, and conduct mutual beneficial cooperation with all the farming groups.

(3) The mainstay farmers are the beneficiaries of existing policies and regulations, including the consistent rural land system, the land transfer policies, and other preferential measures for the farmers. These policies and measures provide many advantages, such as access to lands of moderate scale, middle incomes in rural China without being migrant workers (which means they can enjoy complete family lives), ample slack farming time, and leisure times. Therefore, they are inevitably mindful of the rural land policies adopted by the Party and the Chinese government, and support the existing rural land systems and transfer policies.

The mid-level farmer group is the output of the half-industrial and half-agricultural structure. No mid-level farmer will emerge without the moderate scales of lands, which is only acquired by gaining access to the lands transferred by the migrant workers. Furthermore, it is the middle scales of lands that have granted the mid-level farmers corresponding properties and nature and specific positions in the rural social structures, which have further assigned them to corresponding roles in the rural political and social lives– the hardcore.

4.4 Shaping an urbanization path with Chinese characteristics

China has been pressing ahead with urbanization at an annual pace of 1% over the past three decades. However, it has also witnessed many issues over this exceptionally rapid course, such as the impairment of farmers’ rights and interests, forced evictions and demolitions, and the “anti-moving” struggles. Despite this, China’s urbanization is still progressing steadily and making remarkable achievements as we prevented the phenomena of “sheep devour men”─which had forced numerous farmers in western countries to loss their lands─and the massive slums in the modern third world. China’s urbanization has not been achieved by compromising the prosperity of its vast rural areas. While successful migrant workers managed to support their families and live happy lives in urban areas, the less achieving ones are still able to live decent lives in their home villages─this is the so-called “urbanization path with Chinese characteristics” (He, 2014).

Along the path of China’s urbanization, both the successful ones who have managed to acquire rural residency and the less achieving ones who are returning to their home villages are shaped by thehalf-industrial and half-agricultural structure in the rural areas. The significance of such a structure lies in that it mitigates the migrant workers’ pressures and burdens, while making them more resilient to the risks in the cities. There is no point in elaborating on “gaining urban residency” or “returning to home villages” under the structural limits of China’s industry mix and migrant workers income levels should there be no half-industrial and halfagricultural structure.

4.4.1 The half-industrial and half-agricultural structure provides strong backing for “the migrant workers capable of gaining urban residency”

While it is a shared dream of farmers and migrant workers to gain urban residency, only 10% of them will be fortunate enough to seize the opportunity to move into cities and gain permanent urban residency. Gaining an urban residency is no easy mission. It is a prolonged and tough process for every migrant worker, over the course of which he/she will have to keep trying and constantly be subject to the half-industrial and half-agricultural divisions of works and income structures. (1) While the migrant couples are striving for their urban residency, it is of the utmost significance for them to make a proper division of labor and cooperation between generations. Most of the migrant workers achieved this objective mainly by earning and accumulating salaries, thus progressively acquiring and gathering the economic and social capital required to support their lives and family spending in urban areas. Nonetheless, what cannot be underestimated is the explicit and implicit benefits of the old farming at home, which have not only contributed to the migrant workers’ efforts for their urban residency, but more importantly relieved their burdens. The middle and old-aged have created a steady “home” for the migrant workers “making efforts” in the cities by attending farmlands, taking care of their grandchildren, and supporting themselves later years. The migrant workers are thus enabled to go forward with their burdens discarded. Assume that the migrant workers must fight for urban residency while supporting the elderly and finishing labor force reproduction in the “high cost”urban areas, their efforts for keeping a foothold there would either be in vain or throttled when their energy and capital are exhausted. (2) Even after achieving what they have longed for, most of the rural households retain their half-industrial and halfagricultural structure─namely, while the young couples are living in the cities (half-industrial), their parents still live their later years and pass away in the villages (half-agricultural). Should the elderly abandon agriculture and move into the cities, the young couple would be forced to support the whole family─which could have been supported by incomes from both industry and agriculture─with the sole income from their industrial salaries. In this case, they will suffer from multiplied economic stress and declining living standards. By having the old live by themselves later years and pass away in the villages, the migrant workers’ life spending will be remarkably reduced, thus helping to support their families and live decent lives in the cities.

4.4.2 The half-industrial and half-agricultural structure has provided favorable environments for those less achieving returning home migrant workers

Up to 90% of farmers will not have the luck or opportunities to gain urban residency. Their experience of being migrant workers is accompanied by multiple trips between the cities and their villages. Eventually, they will end up coming back to the rural areas. These farmers make multiple attempts to gain their urban residency. They will finally find it unrealistic after several attempts and make the decision to return to their village. In such cases, being a migrant worker has become a method, instead of a purpose, for these farmersto acquire decent lives after they come back from cities. During this course: (1) The old are providing a crucial material basis for the homecoming migrant workers and the precondition of them working in the cities by cultivating their lands and looking after the grandchildren. The couples will be less likely to move into cities if their parents and children cannot settle down at home. (2) The efforts the middle and old aged farmers made to attend the lands, children, and social relations in the villages, is the reason why the migrant workers can still have “destinations” for their homecoming. They will have “nowhere to go”when they are forced to come back (e.g., when they are laid off by financial crisis) if their parents also moved into the cities. (3) One of the preconditions for the half-industrial and half-agricultural structure is the collective land ownership in the rural areas. The lands will become the living guarantees of the homecoming migrant workers after they have made multiple trips between the cities and the villages (or come back after being displaced). They will have life journeys featured by half-industrial and halfagricultural experiences once they have (finally) returned to agriculture─they have been industrial workers at early ages and farmers in later years. The savings from industrial works and the life guarantees provided by their lands are sufficient for them to live decent lives at home. In other words, the half-industrial and half-agricultural structure in rural China has enabled the farmers to “move out”and “come back” during urbanization─they are never concerned with the risk of becoming homeless posed by a failed attempt for “urban residency.”

5. The half-industrial and halfagricultural structure as a mid-level concept

As a descriptive concept, the half-industrial and half-agricultural structure clearly describes and outlines a series of common micro-phenomena in today’s rural areas, including the inter-generational division of labor, the industrial and agricultural incomes of rural households, the vocational differentiation of farmers, the multiple trips between cities and villages made by migrant workers, and the transfer and convergence of lands, etc. However, the rural half-industrial and half-agricultural structure is far more than a descriptive concept. It is also an analytic, or a relational concept which describes the prominence of the specific attributes of an object series─in a word, it evaluates whether and how much the elements are relevant to each other. A descriptive concept only provides static descriptions on all the elements of a phenomenon, instead of explaining the correlations among them. In contrast, an analytic concept provides dynamic statements on the correlations among all elements. There are macro and meso-analytic concepts. The former stands for a highlyAbstractphilosophical concept, and the latter a mid-level concept that falls between a macro and a micro concept. Focusing on general microsocial issues and proposing feasible and practical theoretical hypothesis, a meso-analytic concept is something factual and with value orientation. In a word, the half-industrial and half-agricultural structure captures the basic implications of a midlevel concept.

The half-industrial and half-agricultural structure represents the organic combination between its inherent phenomena and elements, thus constituting a stable morphology carrying its own mechanisms and logic. On one hand, the rural half-industrial and half-agricultural structure includes a series of phenomena it has described and outlined, namely such a structure is theAbstractrefinement of these micro-phenomena. On the other hand, its inherent phenomena are to some extent correlated logically with each other, which means it is possible to infer other phenomena viathe intermediate variables. Therefore, it is feasible to raise a hypothesis and establish chain relationships among phenomena, thus making arguments through the phenomena and facts. Chain relationships refer to the logical relationships among no less than three phenomena. It is possible to construct at least several pairs of chain relationships (see Figure 2).

(1) Constructing the chain relationship between the new three-generation families and the farmers for risk confrontation

The inter-generational division of labor is an inherent phenomenon of the rural half-industrial and half-agricultural structure in China. That the old engage in agriculture and the young couples work in cities constitutes the basic model of rural inter-generational division of labor, leaving the rural family structure in a long-term status of “inseparable family separation,” which has resulted in the common “new three-generation families” in today’s rural areas. Such a pattern differentiates itself from the traditional stem and joint families, nor does it resemble the nuclear family in western terms as it ensures that a farmer’s family is jointly supported by the three generations–who also stand shoulder to shoulder to cope with the risks in the cities and the social competitions at home.

(2) Constructing the chain relationship between the middle incomes and the rural stabilizers. The half-industrial and half-agricultural structure families have incomes from both sectors, making most of them the middle-incomes in rural China. Being satisfied with their status quo, the conservative rural middle incomes have laid concrete foundations for the stability in rural China.

(3) Constructing the chain relationship between gray hair agriculture and the rural families’engagement in social competitions. The halfagricultural middle and old-aged, or the eldly agriculture, is an integral part of the half-industrial and half-agricultural structure. The gray hair agriculture is crucial to the half-industrial and half-agricultural families for cost-effective finishlabor force reproduction and engagement in social competitions.

Figure 2 The half-industrial and half-agricultural structure as a mid-level concept

(4) Constructing the chain relationship between the features of mainstay agriculture and the deinvolution process. The half-industrial nature of this structure implies that it is inevitable for some rural families to transfer their lands to others. As a result, the ones who acquired these lands will have access to lands of moderate scale, forming mainstay agriculture. With its focus on efficiency and profitability of scale, mainstay agriculture represents the tendency towards de-involution.

(5) Constructing the chain relationship between the mainstay farmers and the reliant forces and villages’ political structures. As the principal part of mainstay agriculture, the hardcore farmers’social nature and their unique positions in rural social structures have made them a reliable force for the Party and Chinese government to implement their policies and regulations in the rural areas. The mainstay farmers are vigorous players in the rural political landscapes.

(6) Constructing the chain relationships between the rural land systems and China’s urbanization path. The rural collective ownership system is the precondition to the half-industrial and halfagricultural structure. The farmers are enabled to go back and forth between cities and villages as long as they have lands at home.

Therefore, they would repeatedly make multiple attempts to gain urban residency, instead of giving up after one single failure. At the end of the day, only a group of farmers who are more successful will manage to settle down in the cities, while the less achieving ones will return to their lands. During this course, the half-industrial and half-agricultural structure has demonstrated notable elasticity. In other words, the farmers have the flexibility to seek industrial jobs while they can, or return to their lands. Farmers who are more capable will have access to urban residency, and those less achieving still have their access to industrial and agricultural incomes, thus living decent lives at home─that is China's unique urbanization path.

In these chain relationships, the rural halfindustrial and half-agricultural structure could either be an intermediate variable or a primary variable, from which other intermediate variables can be derived. By doing this, the intermediate variables will bridge all the phenomena and elements in a logical manner, and form further explanation chains. Moreover, other significant political, economic, and social phenomena can be explained and set forth through the permutations and combinations of their inherent phenomena. In this sense, it makes sense to define the rural half-industrial and half-agricultural structure as an analytic middle range concept.

Specifically, the rural half-industrial and half-agricultural structure is mostly defined as a phenomenon reflecting the incomes and division of labor of rural households in the existing analysis. In-depth investigations have been conducted by leveraging this definition. As a result, few analyses have defined it as an analytic concept. This article constitutes an attempt for the analysis of the rural half-industrial and half-agricultural structure from two dimensions: On the macro dimension, it proceeds from the dissections and estimations of China’s economic development in the long run, the income levels of migrant workers, and the institutional urbanrural dual structure; on the micro level, it puts the foothold on the elaboration and detailed analysis of the differentiation of rural managing subjects, the behavioral logic of farmers, and the work division strategies of rural families. By capturing all the phenomena–economic, social, political, family, individual and their chain relationships, this concept explains the diverse socioeconomic and sociopolitical phenomena well in rural China.

(Translator: Wu Lingwei; Editor: Yan Yuting)

This paper has been translated and reprinted with the permission of Issues on Agricultural Economy, No.9, 2015.

REFERENCES

Chen Bofeng. (2014). Rural middle income strum in the rural-urban dual structure. Social Science.

He Xuefeng. (2004). The rising of mainstay farmers. The Journal of Humanities.

He Xuefeng. (2007). The future of villages. Jinan: Shandong People's Publishing House.

He Xuefeng. (2011). On village managed by the rich—Discussion on the investigation of Fenghua in Zhejiang Province. Social Science Research, 2.

He Xuefeng. (2014). An urbanization path of Chinese characteristics. Oriental Press.

Huang Zongzhi. (2006). The institutionalized involution agriculture of half- industrial and half-agricultural structure. On Reading,2.

Huang Zongzhi. (2010). China's hidden agricultural revolution. Law Press China.

Huang Zongzhi. (2013).China’s modern families: From the historic prospective of the economy and law. Open Times, 5.

Jing Jun, Wu Xueya & Zhang Jie. (2010). The migration of rural females and the declination of China’s suicide rates. Journal of China Agricultural University (Social Science Edition),4.

Xia Zhuzhi. (2014). On the sociological implications of the half-industrial and half-agricultural structure. The Journal of Humanities.

Xu Jiahong. (2012). The mid-level agricultural phenomenon in the rural land transfer–A field survey based on Z village in north Jiangxi. Guizhou Social Sciences,4.

Yang Hua & Fan Fangxu. (2009). Suicide order and the elderly suicides of Jingshan Village of Hubei Province; Open Times,5.

Yang Hua & Ouyang Jing. (2013). Stratification, Inter-generational Exploitation, and the Elderly Suicides in the Rural Areas. Management World,5.

Yang Hua.(2013). The mainstay class: The central class in contemporary rural society. Open Times,3.

Yang Hua.(2013). Various types of land transfer and their implications in the context of stratification. Journal of the Party School of CPC Hangzhou Municipal Committee,3.

Yu Lian & Liu Yang. (2013). Villages of migrant families: another presentation of China’s small peasant economy. Journal of Nanjing Agricultural University (Social Science Edition), 6.

*This article attempts to summarize the discussions on the rural half-industrial and half-agricultural structure by Professor He Xuefeng and the Central China School of Rural Studies.

*Yang Hua, School of Marxism, Huazhong University of Science & Technology.

Contemporary Social Sciences2017年3期

Contemporary Social Sciences2017年3期

- Contemporary Social Sciences的其它文章

- Bashu Culture and Du Fu’s Poetic Space

- The Contemporary Value and Significance of Chinese Culture

- Diversity and Innovation: Progress and Exploration of Domestic Art Movies in 2016

- Tao, Virtue, Benevolence, Righteousness and Propriety: On the Core Values of Shu School

- Historical Starting Point, Contemporary Vision and World Insight— New Thinking for the Study of Ancient Chinese Capitals

- Dislocated Character Affirmation— A Case Study of Young Female Gamers’ Identity in Online Games