地球化学方法在硅质岩成因与构造背景研究中的进展及问题

张 聪, 黄 虎, 侯明才

(1.中国地质大学 地球科学与资源学院,北京 100083;2.中国地质调查局 油气资源调查中心,北京 100029;3.成都理工大学 沉积地质研究院,成都 610059)

地球化学方法在硅质岩成因与构造背景研究中的进展及问题

张 聪1,2, 黄 虎3, 侯明才3

(1.中国地质大学 地球科学与资源学院,北京 100083;2.中国地质调查局 油气资源调查中心,北京 100029;3.成都理工大学 沉积地质研究院,成都 610059)

硅质岩由于受后期风化作用及成岩作用影响较弱,其地球化学特征常被用来讨论硅质岩成因和形成构造背景。本文分析了硅质岩的成因以及形成于不同构造背景下硅质岩的主元素、痕量元素、稀土元素、Si同位素和Sr-Nd同位素组成特征。在总结硅质岩成因与构造背景研究方法和进展的同时,指出元素地球化学行为的错误理解和硅化作用过程中SiO2稀释剂作用的影响是造成利用地球化学方法判别硅质岩成因和构造背景时产生多解性的主要原因。而对硅质岩成岩机理的再认识表明:硅质岩成岩过程中,SiO2对主元素和稀土元素起稀释剂的作用;TiO2、Al2O3、MgO、K2O作为陆源组分,受成岩作用的影响比Fe2O3、MnO、CaO、Na2O、P2O5弱;成岩作用对页岩或泥岩主元素的影响强于硅质岩;硅质岩的稀土元素含量除受沉积环境的控制外,还受硅化程度的影响。

硅质岩;地球化学;成因;成岩作用;构造背景

硅质岩相对于其他沉积物(砂岩、碳酸盐等)分布较少,但是从太古代到新生代均有其沉积记录。由于硅质岩很少受后期风化作用及成岩作用的影响,其地球化学特征记录了热液沉积、火山及陆源碎屑等的含量变化,对恢复古环境具有重要的意义[1-4]。因此,硅质岩的地球化学特征常用来讨论其成因和形成构造背景[5-10]。随着越来越多有关硅质岩地球化学数据的报告,目前在利用硅质岩的地球化学数据讨论其成因和构造背景时,常会出现多解性和人为性[11]。本文在总结前人利用硅质岩地球化学特征判断成因和构造背景进展的同时,分析造成目前利用硅质岩判别成因时多解性的部分原因,并讨论硅质岩成岩过程中部分元素的地球化学行为。

1 SiO2的来源

由于缺少硅质微生物,目前对前寒武纪硅质岩中的SiO2的起源还有较大争议,主要存在以下几种假设:从海水中直接沉淀硅[12],深海热液硅[13-14],陆源或混合陆源组分的蒸发岩经硅化作用生成[15]等。一般认为,显生宙以来的硅质岩中SiO2的起源主要与硅质生物活动有关[16]。研究表明,现代海洋中的溶解态硅80%来自河流的输入,剩余部分则主要来自大气﹑海底玄武岩的低温风化和海底热烟囱[17],并由富硅生物吸收以及死亡分解后,约3%的生源硅沉降形成A型蛋白石,再经过CT型蛋白石沉降与溶解过程,最后转化为硅质岩[17-18]。另外,热液活动有关的硅化作用、碳酸盐中硅的置换作用[19]以及强碱条件下从胶体中沉淀[20-21]等在特定的沉积环境中均可能成为硅质岩成岩过程中SiO2的重要来源。

2 硅质岩的成因

硅质岩由于受后期成岩作用改造,其原始组构可能发生改变,进而造成直接的矿物学证据缺失。目前,对于硅质岩成因类型的研究主要依靠地球化学手段[22]。硅质岩中的Fe和Mn的富集被认为主要与热液的参与有关,而Al和Ti的富集则主要与陆源物质的输入有关。据此,有学者[23]认为海相沉积物中的wAl/wAl+Fe+Mn值(w表示质量分数)可以用来衡量沉积物中热液组分含量,该比值越小,反映其受热液作用影响越明显。Adachi等[24]和Yamamoto[25]在系统研究了不同成因的硅质岩后,拟定了判别热液成因与非热液成因硅质岩的wAl-wFe-wMn三角判别图解。在该判别图解上,非热液成因硅质岩的投点均落入富Al端元,而热液成因硅质岩的投点均落入富Fe端元。对大西洋中脊和东太平洋海隆的热液沉积物研究表明,热液沉积物的稀土元素经球粒陨石标准化后均表现为明显的Eu正异常[26-29]。另外,热液硅质岩中除了含大量微晶质石英及少量黏土矿物外,常含有呈分散状的褐铁矿、方沸石、蒸发岩、石膏、硬石膏、自生的重晶石及黄铁矿等矿物或其假晶[13-14,30]。

目前有关硅质岩成因的研究主要借助于wAl-wFe-wMn判别图[24-25]以及(wAl/wAl+Fe+Mn)-(wFe/wTi)判别图[31]。这些成因判别图中均利用Mn元素作为热液成因的指示元素,而Murray[32]指出Mn元素容易受成岩作用的影响,是一种相对易迁移的元素。考虑到这种原因,本文将已发表的显生宙不同成因的硅质岩样品[1,24-25,33-42]投在(wAl/wAl+Fe)- (wFe/wTi)图解(图1-A)上,并与wAl-wFe-wMn判别图(图1-B)对比,可以发现2个判别图的结果基本一致。即当wAl/wAl+Fe>0.5、wFe/wTi<30时,代表非热液成因;而当wAl/wAl+Fe<0.35、wFe/wTi>30时,代表热液成因。

3 硅质岩的构造背景判别

3.1 主元素

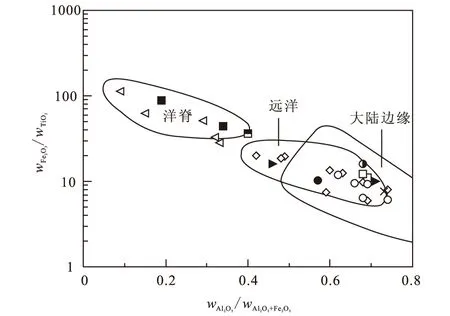

Murray[32]在系统地总结了显生宙形成于不同构造背景的硅质岩地球化学特征后,认为Al和Ti元素可以作为陆源物质注入的标志,并根据Al2O3、TiO2、Fe2O3和SiO2的比值关系,提出了区分洋中脊、大洋盆地和大陆边缘硅质岩的判别图。目前,wAl2O3/wAl2O3+Fe2O3值被认为是判别硅质岩形成构造背景的一个较好的指标[32,39,44-45]。其中,大陆边缘硅质岩的wAl2O3/wAl2O3+Fe2O3=0.5~0.9;远洋盆地硅质岩的wAl2O3/wAl2O3+Fe2O3=0.4~0.7;而洋中脊硅质岩的wAl2O3/wAl2O3+Fe2O3<0.4[32]。

图2 硅质岩构造背景判别图Fig.2 Discrimination diagram of tectonic setting for cherts(据文献[32]修改, 图例同图1)

Murray等[32]系统总结了显生宙不同环境硅质岩的地球化学特征,提出用(wAl2O3/wAl2O3+Fe2O3)-(wFe2O3/wTiO2)(图2)来判别硅质岩的形成环境。比较图1-A和图2可以发现二者表现出很好的相似性。这种相似性主要归因于Fe元素的富集与热液成因有关,而其富集势必会造成Fe2O3的富集,进而在构造背景判别图上指示远洋或洋脊环境;而Al和Ti元素主要与陆源组分有关,其富集指示陆源成因,而Al和Ti元素的富集必然会造成Al2O3和TiO2的富集,进而在构造背景判别图上指示大陆边缘环境。那么,是否意味着这2个判别图都可以同时用来判别硅质岩的成因以及构造背景呢?实际上从图1-A中可以看出,热液成因的硅质岩主要形成于半深海、洋脊以及开阔海盆相关的环境,而非热液成因的硅质岩主要形成于远洋、大陆边缘以及大陆架相关的环境。从图2中可以看出,由于受热液作用的影响,部分形成于岛弧环境的硅质岩投点落在远洋区,而部分形成于半深海及开阔海盆环境的硅质岩投点落在图上的洋脊区。这种现象表明,(wAl/wAl+Fe)-(wFe/wTi)图可以用来判别硅质岩的成因,而不能用于判别其构造背景;而(wAl2O3/wAl2O3+Fe2O3)-(wFe2O3/wTiO2)图可以用于判别硅质岩的成因,却不能准确地判别部分硅质岩的形成环境。目前已有不少研究[46-47]开始利用(wAl2O3/wAl2O3+Fe2O3)-(wFe2O3/wTiO2)图解来判断硅质岩的成因而不是其形成的构造背景。上述现象出现的原因主要在于wAl/wAl+Fe值与(wAl2O3+wFe2O3)值以及wFe/wTi值与wFe2O3/wTiO2值本身就存在内在的定量关系。此外,热液流体可以产生于海底深大断裂、弧后盆地、洋脊、裂谷、岛弧、热泉等多种环境,与基性火山岩的喷出有关[24-25,48]。因此,不能简单地通过硅质岩地球化学判别图来分析其形成的构造背景,还必须结合与硅质岩伴生的岩石组合的特征综合分析其形成环境。

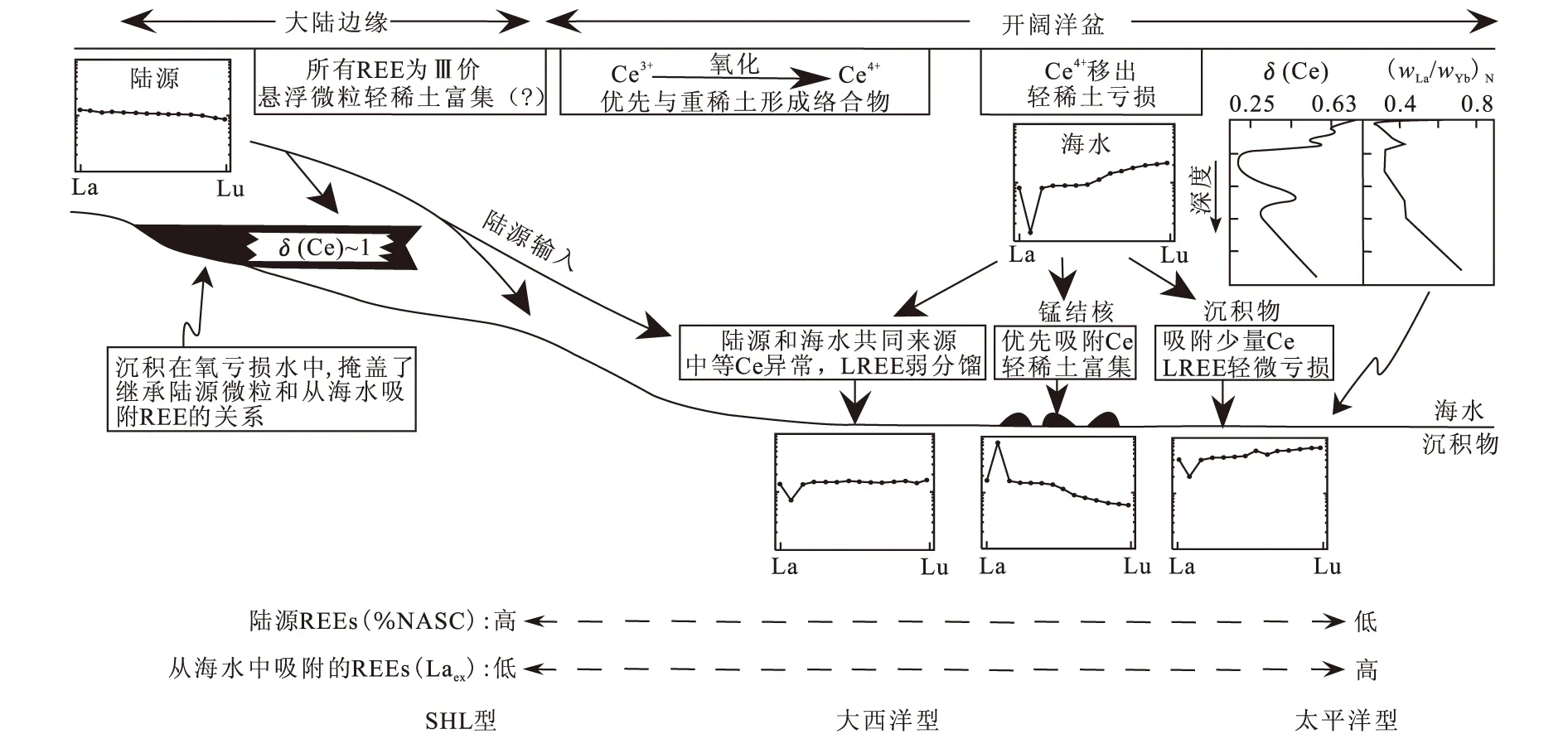

3.2 稀土元素

由于海水中Ce3+容易被氧化为溶度积相对较小的Ce4+,Ce4+被铁锰氢氧化物、有机物微粒或结核吸附,进而造成海水中剩余的溶解态Ce相对的亏损[49-50]。Murray等[34,51]通过对美国弗朗西斯科杂岩中硅质岩的研究分析,总结了形成于不同构造环境硅质岩的地球化学特征。其中,硅质岩中的稀土元素质量分数(w∑REE)和铈异常δ(Ce)主要由海水中陆源输入量、金属物质及埋藏速率控制。在洋脊及附近环境中,高埋藏速率减少了沉积物在海水中的暴露时间,进而限制了从海水中吸附稀土元素,造成硅质岩具有较低的稀土元素含量。在开阔洋盆环境中,从海水中的吸附作用控制了硅质岩的稀土元素特征。由于缺少金属粒子及陆源物质的输入且具有较低的埋藏速率,形成于开阔洋盆的硅质岩常可以从海水中吸附较多的稀土元素。在大陆边缘环境中,从海水中吸附以及继承陆源微粒中的稀土元素均控制了硅质岩中的w∑REE,而大陆架附近的高埋藏速率则可能限制了吸附作用所扮演的角色。另外,重结晶作用也会使硅质岩富集稀土元素,因此大陆边缘硅质岩中的w∑REE往往具有一定的不确定性[34, 51]。相对于w∑REE的指示意义,δ(Ce)和(wLa/wCe)N对环境的指示意义更明显。其中: 大洋中脊附近的硅质岩δ(Ce)值为0.30±0.13,(wLa/wCe)N≥3.5;开阔洋盆的硅质岩δ(Ce) 值为0.60±0.11,(wLa/wCe)N=2.0~3.0;大陆边缘的硅质岩δ(Ce) 值为1.09±0.25,(wLa/wCe)N值接近1.0[32, 34, 51]。(wLa/wYb)N对区分不同构造环境的硅质岩也具有重要意义[52-54]。Murray等[52]在大洋钻探计划和深海钻探计划中总结了不同环境下硅质岩的稀土元素特征(图3)。其中:形成于开阔洋盆环境的硅质岩,由于主要从海水中吸附REE,其稀土元素常表现为轻稀土亏损以及明显的铈负异常,(wLa/wYb)N为0.8~1,并有超过一半的硅质岩样品的w∑REE<50×10-6;形成于受南极大陆大量陆源物质输入影响的被动大陆边缘环境(SHL型)的硅质岩,其稀土元素常表现为轻稀土弱富集的特征,并继承了陆源沉积物的无铈异常的地球化学特征,其(wLa/wYb)N为1.2~1.4,w∑REE平均值为113.7×10-6;而形成于有限洋盆环境 (大西洋型) 的硅质岩,其稀土元素特征则处于上述二者之间,表现为轻稀土略分馏以及中等的铈负异常。

图3 深海钻探计划(DSDP)和大洋钻探计划(ODP)硅质岩的稀土元素行为控制因素综合图Fig.3 Schematic diagram summarizing processes controlling the REE composition of DSDP and ODP cherts(据文献[52])

大陆边缘沉积物如果混入了未分异的火山碎屑则不显示铕负异常[39,55]。Taylor等[56]认为在后太古代沉积物中负铕异常的缺失与火山岩序列第一次循环沉积有密切关系。值得注意的是,对Murray等[34]发表的弗朗西斯科杂岩中形成于不同环境硅质岩的数据处理发现,洋脊及两翼硅质岩(wLa/wYb)N=0.74±0.14,开阔洋盆硅质岩(wLa/wYb)N=1.30±0.84,而大陆边缘硅质岩(wLa/wYb)N=0.75±0.22。可以看出洋脊和大陆边缘硅质岩(wLa/wYb)值明显低于SHL型硅质岩,也明显低于河流沉积物的1.85[57]和上地壳平均组成的1.17[56];而形成于开阔洋盆硅质岩的(wLa/wYb)N值变化较大,但明显高于一般海水的0.5。造成这种结果的原因可能是由于形成于开阔洋盆的岩层被覆盖得太多,所分析的数据较少(共4个硅质岩样品)[34]。但是,日本西南部晚二叠世早期-早三叠世早期远洋硅质岩(n=17)的(wLa/wYb)N=1.00±0.34[1],也反映了硅质岩成岩过程中轻重稀土的分异受多方面因素控制(如硅质岩沉积过程中是否选择性从海水中吸附稀土元素,埋藏速率的快慢与继承性吸附陆源微粒中稀土元素的主次关系,成岩后期改造作用的影响等)。

此外,Pirajno等[30]和Kerrich等[58]分别报告了澳大利亚古元古代裂谷和东非大陆裂谷环境硅质岩的地球化学特征。其中,澳大利亚古元古代裂谷硅质岩(n=10):δ(Ce)=0.91±0.28,δ(Eu)=0.87~20.65,平均值为6.59,(wLa/wCe)N=1.16±0.36,(wLa/wYb)N=0.46±0.40,w∑REE=15.18×10-6±14.48×10-6;而东非大陆裂谷马加迪碱性湖的硅质岩(n=8):δ(Ce)=5.23±4.27,δ(Eu)=0.43±0.05,(wLa/wCe)N=0.32±0.19,(wLa/wYb)N=0.55±0.43,w∑REE=(26.54±14.48)×10-6。2种硅质岩均形成于伴生有热泉的浅水碱性盐湖环境,均表现为较低的(wLa/wCe)N、(wLa/wYb)N、w∑REE值以及相对开阔洋盆和洋脊环境硅质岩较高的铈异常值。但是,马加迪碱性湖的硅质岩却表现出明显的铈正异常[δ(Ce)最大值为14.2],明显的铕负异常;而澳大利亚古元古代裂谷环境硅质岩则具有较弱的铈异常,明显的铕正异常[仅1个样品δ(Eu)=0.87,其他δ(Eu)均大于1.8],并含重晶石。前者硅质岩的形成主要与继承高碱性流体(其高碱性水环境pH>10.5)化学组成有关[58],后者则与热液流体的参与有很大关系[30]。

3.3 痕量元素

痕量元素中的某些元素含量也可能是判别硅质岩成因及沉积-构造环境的指标。Girty等[39]、Kato等[13]先后对硅质岩中的Th、U、Sc和Cr含量对物源及构造环境的指示意义做了部分研究。其中,形成于大陆边缘环境的硅质岩具有较高的wTh/wSc值(1左右)以及wTh/wU值(一般大于3.8);而形成于相对远离大陆边缘环境的硅质岩常具有较低的wTh/wSc值(0.01~0.3)和wTh/wU值(0.6~5.0)[39,59]。李献华[45]总结Murray等[34]发表的形成于不同环境硅质岩的痕量元素特征,发现洋中脊和大洋盆地硅质岩的V含量明显高于大陆边缘硅质岩,而Y含量则相反,洋中脊和大洋盆地硅质岩的wV/wY明显高于大陆边缘硅质岩。赣东北蛇绿混杂岩带中硅质岩wTi/wV=42~97,wV/wY<2.6,与大陆边缘硅质岩相当(wTi/wV≈40,wV/wY≈2.0),明显不同于洋中脊硅质岩 (wTi/wV≈7,wV/wY≈4.3)和大洋盆地硅质岩 (wTi/wV≈25,wV/wY≈5.8)[45]。南天山库米什铜花山地区蛇绿混杂岩带中与泥岩互层产出的红色硅质岩的wTh/wSc=0.56~4.35,其源区物质主要来自未分异岩浆弧;而成夹层产于基性熔岩中的绿色硅质岩的wTh/wSc=0.57~0.87,反映有洋内弧物质的加入[59]。目前,一般认为V、Cr、Ni、As、Sr、Mo、Ag、Cd、Sb、Ba、U等元素的高富集可能与热液活动有关,而Zr、Hf、Ta、Nb、Th等元素的高富集主要与陆源物质的输入有关[1,60]。但是,由于成岩过程中SiO2的稀释剂作用,势必会影响硅质岩中部分痕量元素的地球化学行为,是否可以准确地利用这些痕量元素含量来判断硅质岩的成因和形成构造背景,还有待更多的研究检验。

3.4 Si同位素

3.5 Sr-Nd同位素

Weis等研究认为硅质岩Sr、Nd同位素可以用来探讨其形成年代[71]以及其同位素比值初始值可以很好地判别其形成的构造环境[72]。Kunimaru等[35]和Shimizu等[44]通过对日本二叠系—三叠系大量硅质岩的地球化学及Sr、Nd同位素的研究,探讨了成岩过程中硅质岩的均一化问题,进一步表明硅质岩的Sr、Nd同位素可以用来判别其形成时代和环境。其中,受陆源碎屑输入影响明显的硅质岩有较高的87Sr/86Sr初始比值以及较低的εNd(t)值,而形成于远离大陆边缘环境的硅质岩具有与海水相似的Sr-Nd同位素组成[较低的87Sr/86Sr初始比值以及较高的εNd(t)值][44,72],与形成于相关环境硅质岩的主元素和稀土元素判别结果一致[35,44]。目前,中国有关硅质岩的Sr、Nd同位素的研究应用主要体现在同位素年代学方面[73-75],仅有少量文献涉及硅质岩的形成环境[22,76]。

4 成岩作用过程地球化学行为的讨论

其中:各主元素质量分数经换算后满足wSiO2+wSiO2*=100%,进而可以得到硅质岩中各主元素质量分数之间的理论趋势线(图4)。图中纯硅质岩的各主元素质量分数为假设其SiO2质量分数为99%后据前面的公式计算得到,例如

wAl2O3(纯硅质岩)=

图4 加利福利亚弗朗西斯科杂岩中硅质岩和页岩主元素端元混合模型Fig.4 Mixing models of the major elements in chert and shale from the Franciscan Complex(硅质岩和页岩数据据文献[34])

5 结 论

利用硅质岩元素地球化学特征研究其成因和构造背景时,需要建立在对硅质岩地球化学行为准确理解的同时,考虑硅化作用过程中SiO2稀释作用的影响,并需要结合其他岩石成因环境及古地理环境综合考虑,而不能单独依靠硅质岩的某一项地球化学指标进行判别。相对于硅质岩的主元素、痕量元素以及稀土元素对其成因及其大地构造背景的指示作用的广泛应用,有关硅质岩同位素的研究与应用相对较少,随着研究方法和测试技术的提高,这些都有待进一步的探索。

[1] Kato Y, Nakao K, Isozaki Y. Geochemistry of Late Permian to Early Triassic pelagic cherts from southwest Japan: Implications for an oceanic redox change [J]. Chemical Geology, 2002, 182(1): 15-34.

[2] Ran B, Liu S G, Jansa L B,etal. Origin of the Upper Ordovician-Lower Silurian cherts of the Yangtze block, South China, and their palaeogeographic significance [J]. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences, 2015, 108: 1-17.

[3] 黄虎,杜远生,黄志强,等.桂西晚古生代硅质岩地球化学特征及其对右江盆地构造演化的启示[J].中国科学:地球科学,2013,43(2):304-316. Huang H, Du Y S, Huang Z Q,etal. Depositional chemistry of chert during late Paleozoic from western Guangxi and its implication for the tectonic evolution of the Youjiang Basin [J]. Science China: Earth Sciences, 2013, 43(2): 304-316. (in Chinese)

[4] 黄虎,杨江海,杜远生,等.右江盆地北缘上二叠统碎屑岩和硅质岩地球化学特征及其地质意义[J].地球科学,2012,37(S2):81-96. Huang H, Yang J H, Du Y S,etal. Depositional chemistry of clastic rocks and siliceous deposits and its provenance analysis of the Upper Permian on the northern margin of the Youjiang Basin [J]. Earth Science, 2012, 37(S2): 81-96. (in Chinese)

[5] Garbán G, Martínez M, Márquez G,etal. Geochemical signatures of bedded cherts of the upper La Luna Formation in Táchira State, western Venezuela: Assessing material provenance and paleodepositional setting [J]. Sedimentary Geology, 2017, 347: 130-147.

[6] Wang J G, Chen D Z, Wang D,etal. Petrology and geochemistry of chert on the marginal zone of Yangtze Platform, western Hunan, South China, during the Ediacaran-Cambrian transition [J]. Sedimentology, 2012, 59: 809-829.

[7] Hara H, Kurihara T, Kuroda J,etal. Geological and geochemical aspects of a Devonian siliceous succession in northern Thailand: Implications for the opening of the Paleo-Tethys [J]. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 2010, 297(2): 452-464.

[8] Bruce M C, Percival I G. Geochemical evidence for provenance of Ordovician cherts in southeastern Australia [J]. Australian Journal of Earth Sciences, 2014, 61(7): 927-950.

[9] Thassanapak H, Udchachon M, Burrett C,etal. Geochemistry of radiolarian cherts from a Late Devonian continental margin basin, Loei fold belt, Indo-China terrane [J]. Journal of Earth Science, 2017, 28(1): 29-50.

[10] 黄虎,杜远生,杨江海,等.水城—紫云—南丹裂陷盆地晚古生代硅质沉积物地球化学特征及其地质意义[J].地质学报,2012,86(12):1994-2010. Huang H, Du Y S, Yang J H,etal. Depositional Chemistry of Siliceous Deposits of Shuicheng-Ziyun-Nandan Rift Basin in the Late Paleozoic and its Implication for the Tectonic Evolution [J]. Acta Geologica Sinica, 2012, 86(12): 1994-2010. (in Chinese)

[11] 崔春龙.硅质岩研究中的若干问题[J].矿物岩石,2001,21(3):100-104. Cui C L. Some problems in the study of the siliceous rock [J]. Journal of Mineralogy and Petrology, 2001, 21(3): 100-104. (in Chinese)

[12] Robert F, Chaussidon M. A palaeotemperature curve for the Precambrian oceans based on silicon isotopes in cherts [J]. Nature, 2006, 443(7114): 969-972.

[13] Kato Y, Nakamura K. Origin and global tectonic significance of Early Archean cherts from the Marble Bar greenstone belt, Pilbara Craton, Western Australia [J]. Precambrian Research, 2003, 125(3/4): 191-243.

[14] Sugitani K. Geochemical characteristics of Archean cherts and other sedimentary rocks in the Pilbara Block, Western Australia: Evidence for Archean seawater enriched in hydrothermally-derived iron and silica [J]. Precambrian Research, 1992, 57(1/2): 21-47.

[15] Dabard M P. Petrogenesis of graphitic cherts in the Armorican segment of the Cadomian orogenic belt (NW France) [J]. Sedimentology, 2000, 47(4): 787-800.

[16] Maliva R G, Knoll A H, Simonson B M. Secular change in the Precambrian silica cycle: Insights from chert petrology [J]. Geological Society of America Bulletin, 2005, 117(7/8): 835-845.

[17] Treguer P, Nelson D M, Van Bennekom A J,etal. The silica balance in the world ocean: A reestimate [J]. Science, 1995, 268(5209): 375-379.

[18] Hesse R. Origin of chert: Diagenesis of biogenic siliceous sediments [J]. Geoscience Canada, 1988, 15(3): 171-192.

[19] Hesse R. Silica diagenesis: Origin of inorganic and replacement cherts [J]. Earth-Science Reviews, 1989, 26(1/3): 253-284.

[20] Peterson M, Von der Borch C C. Chert: Modern inorganic deposition in a carbonate-precipitating locality [J]. Science, 1965, 149(3691): 1501-1503.

[21] Shaw P A, Cooke H J, Perry C C. Microbialitic silcretes in highly alkaline environments: Some observations from Sua Pan, Botswana [J]. South African Journal of Geology, 1990, 93(5/6): 803-808.

[22] 吕志成,刘丛强,刘家军,等.北大巴山下寒武统毒重石矿床赋矿硅质岩地球化学研究[J].地质学报,2004,78(3):390-406. Lu Z C, Liu C Q, Liu J J,etal. Geochemical studies on the Lower Cambrian witherite-bearing cherts in the northern Daba Mountains [J]. Acta Geologica Sinica, 2004, 78(3): 390-406. (in Chinese)

[23] Bostrom K, Peterson M N A. The origin of aluminum-poor ferromanganoan sediments in areas of high heat flow on the East Pacific Rise [J]. Marine Geology, 1969, 7(5): 427-447.

[24] Adachi M, Yamamoto K, Sugisaki R. Hydrothermal chert and associated siliceous rocks from the northern Pacific their geological significance as indication of ocean ridge activity [J]. Sedimentary Geology, 1986, 47(1/2): 125-148.

[25] Yamamoto K. Geochemical characteristics and depositional environments of cherts and associated rocks in the Franciscan and Shimanto Terranes [J]. Sedimentary Geology, 1987, 52(1/2): 65-108.

[26] Owen R M, Olivarez A M. Geochemistry of rare earth elements in Pacific hydrothermal sediments [J]. Marine Chemistry, 1988, 25(2): 183-196.

[27] German C R, Hergt J, Palmer M R,etal. Geochemistry of a hydrothermal sediment core from the OBS vent-field, 21°N East Pacific Rise [J]. Chemical Geology, 1999, 155(1): 65-75.

[28] Douville E, Bienvenu P, Charlou J L,etal. Yttrium and rare earth elements in fluids from various deep-sea hydrothermal systems [J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 1999, 63(5): 627-643.

[29] Dias A S, Fruh-Green G L, Bernasconi S M,etal. Geochemistry and stable isotope constraints on high-temperature activity from sediment cores of the Saldanha hydrothermal field [J]. Marine Geology, 2011, 279(1): 128-140.

[30] Pirajno F, Grey K. Chert in the Palaeoproterozoic Bartle Member, Killara Formation, Yerrida Basin, Western Australia: A rift-related playa lake and thermal spring environment? [J]. Precambrian Research, 2002, 113(3): 169-192.

[31] Bostrom K, Joensuu O, Valdes S,etal. Geochemical history of South Atlantic Ocean sediments since late Cretaceous [J]. Marine Geology, 1972, 12(2): 85-121.

[32] Murray R W. Chemical criteria to identify the depositional environment of chert: General principles and applications [J]. Sedimentary Geology, 1994, 90(3/4): 213-232.

[33] Sugisaki R, Yamamoto K, Adachi M. Triassic bedded cherts in central Japan are not pelagic [J]. Nature, 1982, 298: 644-647.

[34] Murray R W, Buchholtz Ten Brink M R, Gerlach D C,etal. Rare earth, major, and trace elements in chert from the Franciscan Complex and Monterey Group, California: Assessing REE sources to fine-grained marine sediments [J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 1991, 55(7): 1875-1895.

[35] Kunimaru T, Shimizu H, Takahashi K,etal. Differences in geochemical features between Permian and Triassic cherts from the southern Chichibu terrane, southwest Japan: REE abundances, major element compositions and Sr isotopic ratios [J]. Sedimentary Geology, 1998, 119(3/4): 195-217.

[36] Murray R W, Buchholtz Ten Brink M R, Gerlach D C,etal. Interoceanic variation in the rare earth, major, and trace element depositional chemistry of chert: Perspectives gained from the DSDP and ODP record [J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 1992, 56(5): 1897-1913.

[37] Hein J R, Sancetta C, Morgenson L A. Petrology and geochemistry of silicified upper Miocene chalk, Costa Rica Rift, Deep Sea Drilling Project Leg 69 [J]. Initial Reports of the Deep Sea Drilling Project, 1981, 69: 749-758.

[38] Mpodozis C, Forsythe R. Stratigraphy and geochemistry of accreted fragments of the ancestral Pacific floor in southern South America [J]. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 1983, 41(1): 103-124.

[39] Girty G H, Ridge D L, Knaack C,etal. Provenance and depositional setting of Paleozoic chert and argillite, Sierra Nevada, California [J]. Journal of Sedimentary Research, 1996, 66(1): 107-118.

[40] Armstrong H A, Owen A W, Floyd J D. Rare earth geochemistry of Arenig cherts from the Ballantrae Ophiolite and Leadhills Imbricate Zone, southern Scotland: Implications for origin and significance to the Caledonian Orogeny [J]. Journal of the Geological Society, 1999, 156(3): 549-560.

[41] Kametaka M, Takebe M, Nagai H,etal. Sedimentary environments of the Middle Permian phosphorite-chert complex from the northeastern Yangtze platform, China; The Gufeng Formation: A continental shelf radiolarian chert [J]. Sedimentary Geology, 2005, 174(3/4): 197-222.

[42] Karl S M, Wandless G A, Karpoff A M. Sedimentological and geochemical characteristics of Leg 129 siliceous deposits [C]//Proceedings of the Ocean Drilling Programs, Scientific Results, 129. Ocean Drilling Program, College Station, TX, 1992, 129: 31-79.

[43] Hu Z C, Gao S. Upper crustal abundances of trace elements: A revision and update [J]. Chemical Geology, 2008, 253(3): 205-221.

[44] Shimizu H, Kunimaru T, Yoneda S,etal. Sources and depositional environments of some Permian and Triassic cherts: Significance of Rb-Sr and Sm-Nd isotopic and REE abundance data [J]. The Journal of Geology, 2001, 109(1): 105-125.

[45] 李献华.赣东北蛇绿混杂岩带中硅质岩的地球化学特征及构造意义[J].中国科学:地球科学,2000,30(3):284-290. Li X H. Geochemistry of the Late Paleozoic radiolarian cherts within the NE Jiangxi ophiolite mélange and its tectonic significance [J]. Science China: Earth Sciences, 2000, 30(3): 284-290. (in Chinese)

[46] Yamamoto K, Nakamaru K, Adachi M. Depositional environments of “accreted bedded cherts” in the Shimato terrane, Southwest Japan, on the basis of major and minor element compositions [J]. The Journal of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Nagoya University, 1997, 44: 1-19.

[47] Takayanagi Y, Yamamoto K, Yogo S,etal. Depositional environment of the Cretaceous Shimanto bedded cherts from the Fukura area, Kochi Prefecture, inferred from major element, rare earth element and normal paraffin compositions [J]. The Geological Society of Japan, 2000, 106(9): 632-645.

[48] Snyder W S. Manganese deposited by submarine hot springs in chert-greenstone complexes, western United States [J]. Geology, 1978, 6(12): 741-744.

[49] Liu Y G, Miah M, Schmitt R A. Cerium: A chemical tracer for paleo-oceanic redox conditions [J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 1988, 52(6): 1361-1371.

[50] Holser W T. Evaluation of the application of rare-earth elements to paleoceanography [J]. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 1997, 132(1): 309-323.

[51] Murray R W, Buchholtz Ten Brink M R, Jones D L,etal. Rare earth elements as indicators of different marine depositional environments in chert and shale [J]. Geology, 1990, 18(3): 268-271.

[52] Murray R W, Buchholtz Ten Brink M R, Gerlach D C,etal. Rare earth, major, and trace element composition of Monterey and DSDP chert and associated host sediment: Assessing the influence of chemical fractionation during diagenesis [J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 1992, 56(7): 2657-2671.

[53] Owen A W, Armstrong H A, Floyd J D. Rare earth element geochemistry of upper Ordovician cherts from the Southern Uplands of Scotland [J]. Journal of the Geological Society, 1999, 156(1): 191-204.

[54] Owen A W, Armstrong H A, Floyd J D. Rare earth elements in chert clasts as provenance indicators in the Ordovician and Silurian of the southern Uplands of Scotland [J]. Sedimentary Geology, 1999, 124(1): 185-195.

[55] McLennan S M, Taylor S R, McCulloch M T,etal. Geochemical and Nd-Sr isotopic composition of deep-sea turbidites: Crustal evolution and plate tectonic associations [J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 1990, 54(7): 2015-2050.

[56] Taylor S R, McLennan S M. The Continental Crust: Its Composition and Evolution [M]. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications, 1985: 9-56.

[57] Goldstein S J, Jacobsen S B. Nd and Sr isotopic systematics of river water suspended material: Implications for crustal evolution [J]. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 1988, 87(3): 249-265.

[58] Kerrich R, Renaut R W, Bonli T. Trace-element composition of cherts from alkaline lakes in the east African rift: a probe for ancient counterparts [C]//Sedimentation in Continental Rifts. SEPM Special Publication, 2002, 73: 275-294.

[59] 张成立,周鼎武,陆关祥,等.南天山库米什蛇绿混杂岩带中硅质岩的元素地球化学特征及其形成环境[J].岩石学报,2006,22(1):57-64. Zhang C L, Zhou D W, Lu G X,etal. Geochemical characteristics and sedimentary environments of cherts from kumishi ophiolitic mélange in southern Tianshan [J]. Acta Petrologica Sinica, 2006, 22(1): 57-64. (in Chinese)

[60] Yu B S, Dong H L, Widom E,etal. Geochemistry of basal Cambrian black shales and cherts from the northern Tarim Basin, northwest China: Implications for depositional setting and tectonic history [J]. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences, 2009, 34(3): 418-436.

[61] Reynolds J H, Verhoogen J. Natural variations in the isotopic constitution of silicon [J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 1953, 3(5): 224-234.

[62] Allenby R J. Determination of the isotopic ratios of silicon in rocks [J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 1954, 5(1): 40-48.

[63] Epstein S, Taylor H P.18O/16O,30Si/28Si, D/H, and13C/12C studies of lunar rocks and minerals [J]. Science, 1970, 167(3918): 533-535.

[64] Douthitt C B. The geochemistry of the stable isotopes of silicon [J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 1982, 46(8): 1449-1458.

[65] 丁悌平,万德芳,李金城,等.硅同位素测量方法及其地质应用[J].矿床地质,1988,7(4):90-95. Ding T P, Wang D F, Li J C,etal. The analytic method of silicon isotopes and its geological application [J]. Mineral Deposits, 1988, 7(4): 90-95. (in Chinese)

[66] 丁悌平,蒋少涌,万德芳,等.硅同位素地球化学[M].北京:地质出版社,1994:1-102. Ding T P, Jiang S Y, Wang D F,etal. Silicon Isotope Geochemistry [M]. Beijing: Geological Publication House, 1994: 1-102. (in Chinese)

[67] 宋天锐,丁悌平.硅质岩中的硅同位素(δ30Si)应用于沉积相分析的新尝试[J].科学通报, 1989,34(18):1408-1411. Song T R, Ding T P. A new probe of application of silicon isotopicδ30Si in siliceous rocks to sedimentary facies analysis [J]. Chinese Science Bulletin, 1989, 34(18): 1408-1411. (in Chinese)

[68] 沈上越,魏启荣.云南哀牢山带两类硅质岩特征[J].科学通报,2000,45(9):988-992. Shen S Y, Wei Q R. Two kinds of silicalites in Mount Ailao belt, Yunnan Province [J]. Chinese Science Bulletin, 2000, 45(9): 988-992. (in Chinese)

[69] André L, Cardinal D, Alleman L Y,etal. Silicon isotopes in ~3.8 Ga West Greenland rocks as clues to the Eoarchaean supracrustal Si cycle [J]. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2006, 245(1): 162-173.

[70] Van den Boorn S, Van Bergen M J, Vroon P Z,etal. Silicon isotope and trace element constraints on the origin of ~3.5 Ga cherts: Implications for early Archaean marine environments [J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 2010, 74(3): 1077-1103.

[71] Weis D, Wasserburg G J. Rb-Sr and Sm-Nd isotope geochemistry and chronology of cherts from the Onverwacht Group (3.5 AE), South Africa [J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 1987, 51(4): 973-984.

[72] Weis D, Wasserburg G J. Rb-Sr and Sm-Nd systematics of cherts and other siliceous deposits [J]. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 1987, 51(4): 959-972.

[73] 王鹤年,李红艳,王银喜,等.广东大降坪块状硫化物矿床形成时代——硅质岩Rb-Sr同位素研究[J].科学通报,1996,41(21):1960-1962. Wang H N, Li H Y, Wang Y X,etal. Rb-Sr isotope dating of silicalite from the Dajiangping massive sulfide ore deposit, Guangdong Province [J]. Chinese Science Bulletin, 1996, 41(21): 1960-1962. (in Chinese)

[74] 方维萱,胡瑞忠,谢桂青,等.墨江镍金矿床(黄铁矿)硅质岩的成岩成矿时代[J].科学通报,2001,46(10):857-860. Fang W X, Hu R Z, Xie G Q,etal. Diagenetic-metallogenic ages of pyritic cherts and their implications in Mojiang nickel-gold deposit in Yunnan Province, China [J]. Chinese Science Bulletin, 2001, 46(10): 857-860. (in Chinese)

[75] 潘家永,张乾,马东升,等.滇西羊拉铜矿区硅质岩特征及与成矿的关系[J].中国科学:地球科学,2001,31(1):10-16. Pan J Y, Zhang Q, Ma D S,etal. Cherts from the Yangla copper deposit, western Yunnan Province: Geochemical characteristics and relationship with massive sulfide mineralization [J]. Science China: Earth Sciences, 2001, 31(1): 10-16. (in Chinese)

[76] 宋史刚,丁振举,姚书振,等.碧口地块富铁硅岩REE及Nd-Sr同位素组成及其古环境意义[J].矿物岩石,2008,28(3):57-63. Song S G, Ding Z J, Yao S Z,etal. REE and Nd-Sr isotopic compositions of the iron-rich siliceous rock in Bikou Terrane: Implication to ancient sedimentary environment [J]. Journal of Mineralogy and Petrology, 2008, 28(3): 57-63. (in Chinese)

[77] Yamamoto K. A possible mechanism of rhythmic alternation of bedded cherts revealed by their chemical composition [J]. The Journal of Earth and Planetary Sciences, Nagoya University, 1998, 45: 29-39.

[78] McBride E F, Folk R L. Features and origin of Italian Jurassic radiolarites deposited on continental crust [J]. Journal of Sedimentary Research, 1979, 49(3): 837-868.

[79] Ikeda M, Tada R, Sakuma H. Astronomical cycle origin of bedded chert: A Middle Triassic bedded chert sequence, Inuyama, Japan [J]. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2010, 297(3): 369-378.

Progress and problems in the geochemical study on chert genesis for interpretation of tectonic background

ZHANG Cong1,2, HUANG Hu3, HOU Mingcai3

1.SchoolofEarthScienceandMineralResources,ChinaUniversityofGeosciences,Beijing100083,China; 2.OilandGasSurveyCenterofChinaGeologicalSurvey,Beijing100029,China; 3.InstituteofSedimentaryGeology,ChengduUniversityofTechnology,Chengdu610059,China

Silicolite is often used to discuss its genesis and tectonic setting duo to its immobility during the diagenesis and resistant to erosion. In the paper, the origin and major, trace, rare earth elements, Si and Sr-Nd isotopic compositions of cherts from different depositional environments are summarized. The progress and problems in the research of the origin and tectonic setting of cherts and some factors which caused its original multiple solution interpretation are also discussed. Diagenetic process study indicates that the SiO2acts as a diluent of the major elements and REEs during the depositional processes. As terrigenous materials of TiO2, Al2O3, MgO and K2O, the influence from the diagenetic silicification is weaker than that of Fe2O3, MnO, CaO, Na2O and P2O5. It reveals that the influence from the diagenetic silicification for shale or mudstone is stronger than that for chert, and its REEs are controlled not only by the deposition environments but also by the degree of the diagenetic silicification.

cherts; geochemistry; origin; diagenesis; tectonic setting

10.3969/j.issn.1671-9727.2017.03.03

1671-9727(2017)03-0293-12

2017-02-17。

国家自然科学基金项目(41502109); 国家“973”计划项目(2015CB453000); 中国地质调查项目(DD20160178011)。

张聪(1986-),女,博士生,研究方向:地球化学, E-mail:zh_cong520@qq.com。

黄虎(1987-),男,讲师,研究方向:沉积地球化学, E-mail:118huanghu@163.com。

P588.244; P595

A