Strategic mental health planning and its pract ce in China: retrospect and prospect

Bin XIE

•Commentary•

Strategic mental health planning and its pract ce in China: retrospect and prospect

Bin XIE

[Shanghai Arch Psychiatry.2017; 29(2): 115-119. doi: htip://dx.doi.org/10.11919/j.issn.1002-0829.217025]

As a large country with a population of over 1.3 billion people, China has been widely recognized for its roles in economic development and for its participation in global governance. However, China’s efforts in domestic social governance receive both praise and blame. On one hand, the management of a large country that has 18% of the world population, is worth 15.5% of the world economic gross, and is made up of 56 ethnic groups would be a serious challenge to any government or social organization. In the globalization and internet age there is no international experience that can be entirely replicated. China possesses the quality of trial and error from policy design to practice and exploration. However, if China’s reforms in the development of social governance are successful, the immediate and long-term effects are both likely to be significantly enlarged. What adds to the complexity is that there are larger economic, social, and cultural gaps between the different regions within China than there are even between China and other countries at a similar economic level. These factors result in the need for a comprehensive design, omni-directional design, and multi-level testing before national policy adjustment, reform or implementation. The so-called “ideal” or “instructive” paradigm on the international stage could possibly take root in the soil of reality or could likely survive.

1. The basis of mental health work

In the realm of mental health, China’s situation is particularly unique. Stigmatization and discrimination during a long period of history has caused the mental health services to lag behind in China’s economic and social development. The real rapid advancement began around 2000.[1-2]Before the introduction of the National Mental Health Work Plan for 2015-2020 (the New Plan for short[3]) which was referred to by Professor Xiangdong Wang and formulated by 10 departments, the management and services of mental health in China had essentially experienced 3 mutually distinctive and overlapping developmental stages in the past 15 years. The stages were: (a) improving specialized services, (b) integrating with community management services, and (c) improving the mechanism of social coordination.

From 2010 to 2012, China invested 9.1 billion RMB Yuan in the expansion of buildings and operations for the 550 mental health institutions in the country and 1.45 billion RMB Yuan into purchasing equipment necessary for specialized services. Meanwhile, starting with the improvement of patients’ protection through the adjustment of the policies such as financial subsidies and health insurance, there was a rise the specialized medical services’ financing level and indirectly an improvement in treatment service. In order to enhance the professional proficiency of psychiatric teams, there were standardized trainings for physicians and later resident physicians in all 4 zones of China.[4]The above mentioned measures laid the foundation for the mental health service system construct that regarded psychiatric hospitals as the main body.

Taking the development of the Mental Health Center for Disease Control and Prevention and the community management program for severe mental disorders as hallmarks, the community-based mental health service network basically has had its main framework since 2010. This has resulted in the upgrading of community based treatment (originally considered a pilot program)[5,6]and the initial steps in laying the foundation from the National Mental Health Comprehensive Management Pilot, which began in 2015. With the central government establishing the Mental Health Joint Conference in 2007, two rounds of special planning in mental health began, one round from 2002-2010 and the other from 2008 to 2015. It was during this time that various departments and social groups began to form the rough framework for mental health management and services in terms ofdivision of tasks and cooperation between groups. The national mental health law and a number of mental health policies in the past 10 years have also benefited from the formation of this framework.

2. Exist ng resources and condit ons

In China, the current status of services demand and utilization is the following: although the lifetime prevalence of all mental disorders is 17% and severe mental illness is 1%,[7]patients registered in the public health information system[8]as having severe mental illness was less than 0.5% of the total population in most regions. This means that approximately 50% of individuals with severe mental illness were unable or unwilling to receive community based treatment provided by the government.

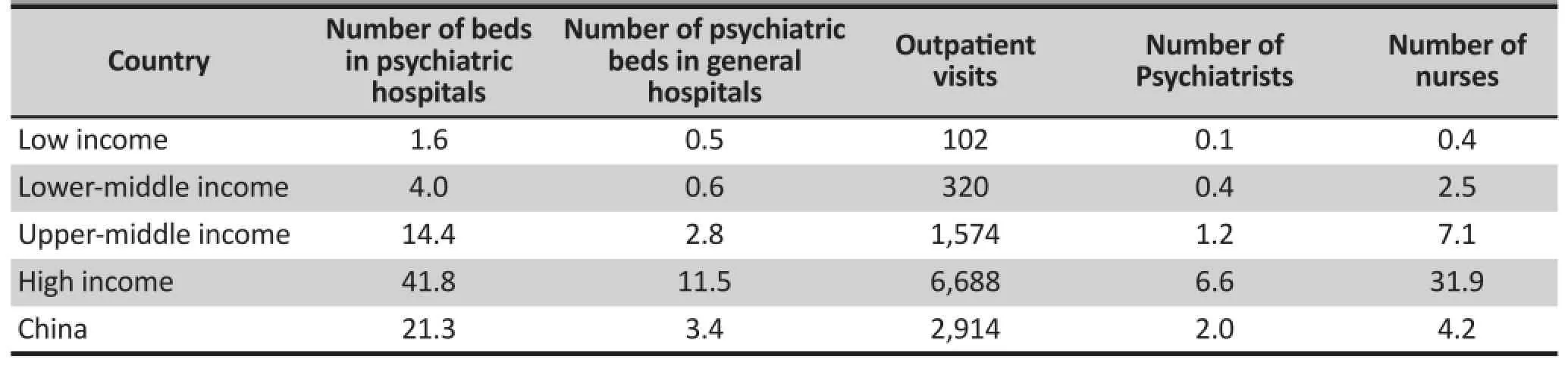

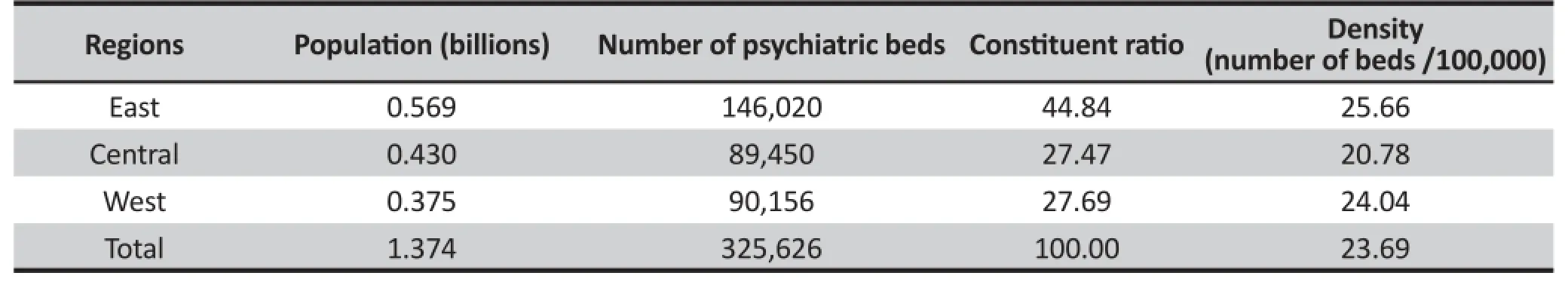

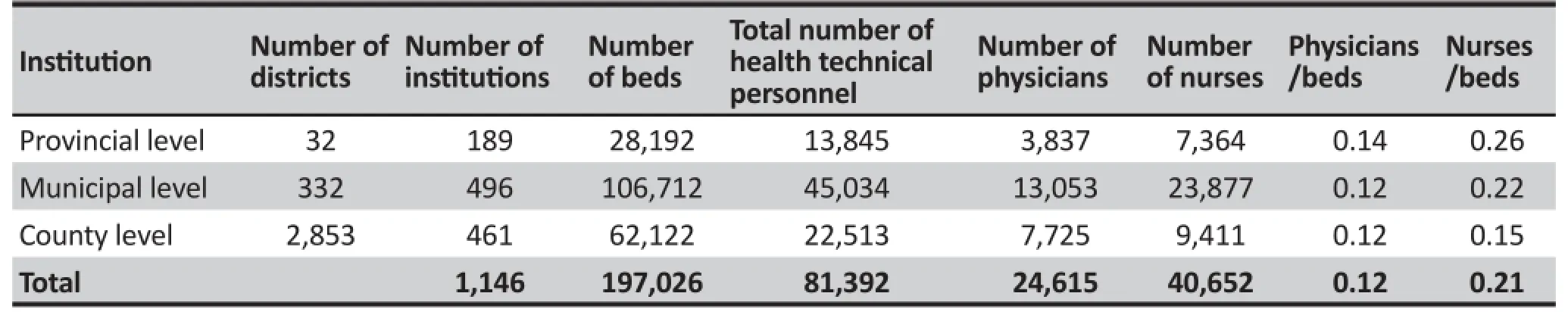

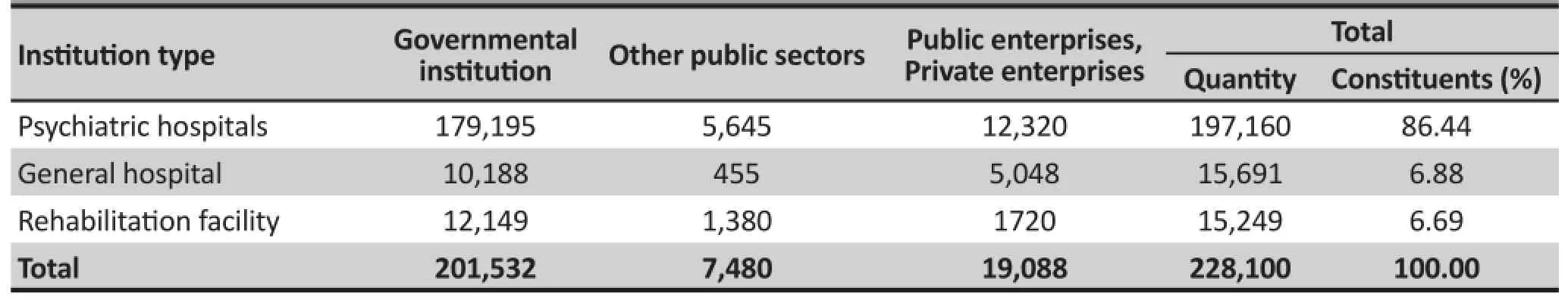

Though the full picture of services utilization and demand has not yet come out, we can say that the service resources in most places are seriously inadequate and mode of services is often outdated and homogenous. As of 2015, in China there were 949 specialized mental health institutions, 27,733 practicing (including assistants) psychiatrists (2.02/100,000 people), 57,591 psychiatric nurses (4.19/100,000 people), and 339,306 psychiatric inpatient beds (24.68/100,000 people). The annual number of outpatient and emergency visits was 40,051,027 (2,914/100,000 people) and the annual number of hospital discharges was 1,987,534 (145/100,000 people).[9]Resources per capita and the quantity of services has increased significantly since 2000 and the numbers have even exceeded the median of the other countries with a similar income level (see table 1).[9-10]However, the gap between resources and needs is still large. For example, according to one study there is still an estimated need for at least 13,000 more psychiatrists in China.[3]Furthermore, the overall pattern of large disparities, both in terms of terms of resources and staffcapability, between China’s regions has not changed in recent years.[11]Psychiatric resources are mainly concentrated in developed areas and in medium and large-sized cities. Rural areas, as well as large portions of central and western China lag far behind in availability of services (see table 2, 3). In addition, China’s mental health system is mostly focused on psychiatry andinpatient services, whereas non-medical support staff, such as psychologists and social workers, are few and far between (see table 4).

Table 1. Domest c and internat onal comparison of mental health service resources and efficie ncy in 2015 (1/100,000 people)

Table 2. Psychiatric beds in different regions of China in 2015

Table 3. Distribut on of mental health resources held by the government in 2010[12]

3. Main strategic areas in the future

Hence, the New Plan is essentially an upgraded version of the policy measures instituted over the past 15 years. The key thrust of the New Plan is to fill in gaps in the current system, not the complete reconstruction of a system.

In this round of current action, what are the major gaps in Chinese mental health? What are the differences between the actual gaps in key areas such human resources, severe mental disorders, depressive disorders, the impact of disasters on mental health, mental health interventions for disasters, suicide prevention and those proposed by the Western Pacific Region Implementation Plan[14]that is supported by the Global Mental Health Action Plan for 2013-2020?[13]

(1) Macro level

On the macro level, the development of human resources in the foreseeable future is still the top priority in Chinese mental health. The major challenges involved include:

A. Needs planning and educational training of all types of mental health related professionals (e.g. physicians, nurses, psychologists, social workers, physical therapists,).

B. Balancing human resources between China’s more developed and lesser developed regions, as well as addressing the resource gap between cities and rural areas.

C. Improving the ability of mental health workers and further professionalizing mental health occupations.

Along with the increase in the mental health workforce, the service system also requires continuous improvements. As can be seen in Table 1, the current psychiatric professional resources in China have basically reached a level that can only meet the needs of primary diseases and behavioral problems. However, the conditions are beginning to improve to the point that a diverse range of mental health needs can be met. Yet the traditional system is becoming an obstacle to these efforts. Challenges in this area that must be addressed include:

A. The popularization and development of mental health services in primary care and general hospitals, especially the provision of non-specialist services in rural areas.

B. Mental health promotion and interventions for certain groups of people including those in the schools, communities and correctional facilities.

C. The development and sustainable operation of the services for the rehabilitation of patients with chronic diseases, as well as nursing home services for elderly patients, etc.

D. Using information technology to link service networks in order to better meet individuals’needs.

As the service system gradually becomes more integrated and service capability improves (particularly with the introduction of policies such as ‘Guidelines for Strengthening Mental Health Services’), from a supplyside reform perspective, China’s mental health service model is bound to usher in a major transformation. Some of the major changes will include:

A. Diversified input, multi-profession participation in services, hierarchical and personalized services will keep increasing.

B. Patient assistance projects with functional rehabilitation as the goal and social support projects aimed at alleviating the burden of disease will be more widely emphasized.

C. The realm of Mental Health Services that focuses on mental health education, psychological counseling, psychotherapy, and psychological crisis intervention will keep growing.

Furthermore, laws and policies that are guaranteed to guide and support the transformation of China’s service model must be developed at the same time. For example, laws that support fiscal policy and the health insurance system, as well as policies that incentivize social involvement in mental health, service evaluation and regulation.

(2) Micro level

Mental health policy and practice are influenced by numerous uncertain factors at the micro level. China’srecent major influence came from a new round of medical reform and mental health legislation.

Table 4. Distribut on of beds in various mental health inst tut ons in 2010[12]

With the implementation of the mental health law in 2013,[15-16]as well as the intensive introduction of 2015-2016 health care policy, the reform of China’s mental health services will also follow in time. The topics that need key research include:

Integration of mental health with other medical and health services.For example, looking at how mental health prevention, medical care and rehabilitation can be leveraged for the further improvement of county-level hospitals, promotion of regional medical integration and partnerships between hospitals.

Function and sustainable development of psychiatric hospitals.There are multiple issues simultaneously adding pressure to the sustainable development of mental health services. Included among these pressures are societal demand to pay more attention to mental health, strict regulation of mental health services by law, a deep rooted societal prejudice against traditional mental health services, reform measures for cost controls in public hospitals, cancellation of drug markups, and finally encouragement of patient movement among physicians and tiered medical services. This final pressure could become the final straw that overwhelms psychiatric hospitals.

Operation and management of mental health services.Health care reform also provides a greater challenge to the internal operation and management of various agencies in the service system. For instance, how do we reinforce quality management, compensate for performance, continuously improve safety and quality, strengthen communication and coordination among various stakeholders, strengthen domestic and international cooperation, and so forth.

More strict regulations on diagnosing and treatment of mental disorders.Protection of patients’ rights and interests is the forever theme of mental health services. How to balance patients’ individual freedom with public interest under a legal framework, including implementation of assessment of severe patients’ risk and the ability to give informed consent, reinforcement of privacy protection, standardization of the clinical treatment for various disorders, and reduction of the rate of long-term hospitalizations , are all urgent problems of China’s psychiatric medical institutions that need to be resolved.

1. Xie B. Challenges and major legislation solution for mental health in China.Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2010; 22(4): 193-199. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3969/ j.issn.1002-0829.2010.04.001

2. Xie B. [Experience and lessons draw from the process of mental health legislation in China].Zhongguo Xin Li Wei Sheng Za Zhi. 2013; 27(4): 245-248. Chinese. doi: http:// dx.chinadoi.cn/10.3969/j.issn.1000-6729.2013.04.002

3. The national health and Family Planning Commission, Office of the Central Committee for Comprehensive Management of Public Security, The National Development and Reform Commission, et al.[Internet] [The national mental health planning work. (2015 - 2020)]. Chinese. Available from: http://www.nhfpc.gov.cn/jkj/ s5888/201506/1e7c77dcfeb4440892b7dfd19fa82bdd. shtml

4. Tang HY, Yu X. [ A general introduction on development of Chinese psychiatric residency standardization training system].Zhongguo Xin Li Wei Sheng Za Zhi. 2011; 25(4): 247-248. Chinese. doi: http://dx.chinadoi.cn/10.3969/ j.issn.1000-6729.2011.04.003

5. Liu J, Ma H, He YL, Xie B, Xu YF, Tang HY, et al. Mental health system in China: history, recent service reform and future challenges.World Psychiatry. 2011; 10(3): 210-216

6. Ma H, Liu J, He YL, Xie B, Xu YF, Hao W, et al. [An important pathway of mental health service reform in China: introduction of 686 Program].Zhongguo Xin Li Wei Sheng Za Zhi. 2011; 25(10): 725-728. Chinese. doi: http:// dx.chinadoi.cn/10.3969/j.issn.1000-6729.2011.10.002

7. Phillips MR, Zhang J, Shi Q, Song Z, Ding Z, Pang S, et al. Prevalence, treatment, and associated disability of mental disorders in four provinces in China during 2001-05: An epidemiological survey.Lancet. 2009; 373(9680): 2041-2053. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60660-7

8. Wang X, Ma N, Wang LY, Yan J, Jin TL, Wu XM, et al. [Management and services for psychosis in People’s Republic of China in 2014].Zhong Hua Jing Shen Ke Za Zhi. 2016; 49(3): 182-188. Chinese. doi: http://dx.chinadoi. cn/10.3760/cma.j.issn.1006-7884.2016.03.012

9. National Health and Family Planning Commission.[2016 China Health Family Planning Statistical Yearbook]. Beijing: Peking Union Medical College press; 2016. Chinese

10. World Health Organization.Mental Health Atlas 2014. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015

11. Liu CP, Chen LJ, Xie B, Yan J, Jin TL, Wu ZG. Number and characteristics of medical professionals working in Chinese mental health facilities.Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2013; 25(5): 277-285

12. Ma N, Yan J, Ma H, Yu X, Guo Y. [Allocation of mental health facilities and psychiatric beds in China in 2010].Zhongguo Xin Li Wei Sheng Za Zhi. 2012; 26(12): 885-889. Chinese. doi: http://dx.chinadoi.cn/10.3969/ j.issn.1000-6729.2012.12.002

13. World Health Organization.Mental Health Action Plan 2013 – 2020. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013

14. WHO Western Pacific Region.Regional Agenda for Implementing the Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020 in the Western Paci fic: Towards a Social Movement for Action on Mental Health and Well-Being. Manila: WHO Western Paci fic Region; 2014

15. The national health and Family Planning Commission, the Central Propaganda Department, the central comprehensive management office, et al. [Internet] The guiding opinions on strengthening the mental health services. Available from: http://www.nhfpc.gov.cn/jkj/ s5888/201701/6a5193c6a8c544e59735389f31c971d5. shtml

16. The Central People's Government of the People's Republic of China [Internet]. People’s Republic of China Mental Health Act. Available from: http://www.gov.cn/flfg/2012-10/26/content_2253975.htm

Bin Xie is the medical director of the Shanghai Mental Health Center of Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine and director of the mental health center at the Shanghai Center for Disease Control and Prevention. His major academic fields of research are forensic psychiatry, mental health policy, and legislation.

Funding

Three year action plan projects for strengthening public health system construction in Shanghai (GWIV-5, PI: Bin Xie);

The National Health and Family Planning Commission research project on mental disease prevention and control (NHFPC DPC-MH 2012-2, NHFPC DPC-MH 2016-53. PI: Bin Xie)

Conflict of interest statement

The author reports no conflict of interest related to this manuscript.

Shanghai Mental Health Center, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China

*correspondence: Bin Xie. Mailing address: 600 South Wanping RD, Shanghai, China. Postcode: 200030. E-Mail: xiebin@smhc.org.cn