[l] and [n] alternations among Sichuan English speakers: An exploratory study

HUANG+Xinyi

【Abstract】The alternation of [l] and [n] is one of the phonological features that distinguish Sichuan English speakers from other Mandarin English speaking groups. This study aims to explore whether the alternation is random, or if it is not, what are the conditions that influence the alternation. The data are from 12 college graduates, who are asked to read a word list as well as a short story containing target sounds. Results show that the alternation is not random. The more frequent direction is [l] changing into [n], and sounds on the right changing into the one on the left.

【Key words】[l] and [n]; Sichuan English

Introduction

In the beginning of the movie My Fair Lady, Professor Higgins impresses everyone with his ability to tell a persons birthplace by the way they speak. He attributes this ability to the “science of speech” (Cukor, 1964), which in fact refers to the phonetic features that speakers from different places have. Not only can peoples first language be evidence of their hometown, their second language can also give a clue. One intriguing observation is that native Sichuan dialect speakers tend to have distinctive ways of articulating [l] and [n] when speaking English. To date, few literature is available to account for the rules underlying the alternation.

As for whether [l] and [n] are interchangeable in Sichuan dialect, the opinions vary. Some scholars suggest that [n] in Sichuan dialect functions as [n] and [l] in Standard Mandarin (Wang 1994, Zhou 2001), and Wang (1994) states that [n] in Sichuan dialect is different from the nasal consonant [n] in Standard Mandarin. Instead, it is a nasalized [l], namely, [l?]. However, Ma & Tan (1998) points out that [l] and [n] both exists in Sichuan dialect, and they are in free variation. Besides, one of the participants interviewed, who is a native speaker of Sichuan dialect, maintains that [l] and [n] are two distinct consonants that are not interchangeable.

Inspired by Hung (2000), who finds that [l] and [n] alternation in Hong Kong English is not random, the present study addresses the following questions:

1. Is alternation of [l] and [n] in English among Sichuan speakers random?

2. If there are rules that underlie the alternation, what are the patterns?

There are two hypotheses: first, when [l] or [n] is in the onset position, the following vowel might affect the alternation; second, when the target sounds are in the middle, the phonological environment might be influential.

Methodology

The speech data were collected from 12 participants, whose mother tongue was Sichuan dialect. All of them were college graduates, which indicated their high proficiency in English. 6 of them were female, and 6 of them were male. 8 were from Faculty of Arts, and 4 were from Science. They aged from 21 to 26. The recordings comprised two separate sessions. The first session consisted of three wordlists totaling 48 words, and the other one was a short story created by the author.

In the wordlists, the target words were categorized as a) [l] and [n] as the onset, b) words with [nl] and [ln] clusters, as well as c) words that had multiple [l]-initial or [n]-initial syllables. The first category was designed to explore whether vowels influenced the alternation, and the other two took the mutual influence between [l] and [n] within a same word into consideration. 10 distractors were mixed in the target words, with an aim to confuse the participants.

The short story was created to include as many target words as possible, with an aim to prove the findings generated from the wordlist. The recordings of the short story were supposed to be more authentic, since the participants probably paid less attention to their pronunciation.

In general, I listened to each of the recordings twice, and repeated the listening for some indistinct ones to get clearer decisions.

Data analysis and discussion

[l] and [n] as the onset

In the first wordlist, 4 vowels, along with 3 diphthongs are chosen to test whether the following vowels affect the alternation. The 4 vowels are from different positions in the IPA vowel chart, ranging from the high front to the low back. As for the words, the ideal situation is that each word in the list has none but one difference from each other, which is the vowel, so that the influence of unrelated factors can be minimized. However, the closest possible is that they all start with [l] or [n], and end with a stop. The results are indicated in the following table.

As shown in the table, there is no significant variance in numbers of alternation between words with different following vowels. Hence, the first hypothesis does not hold water. However, an interesting phenomenon arises that the frequency of [l] changing into [n] far outweighs that of the opposite direction.

[ln] and [nl] clusters

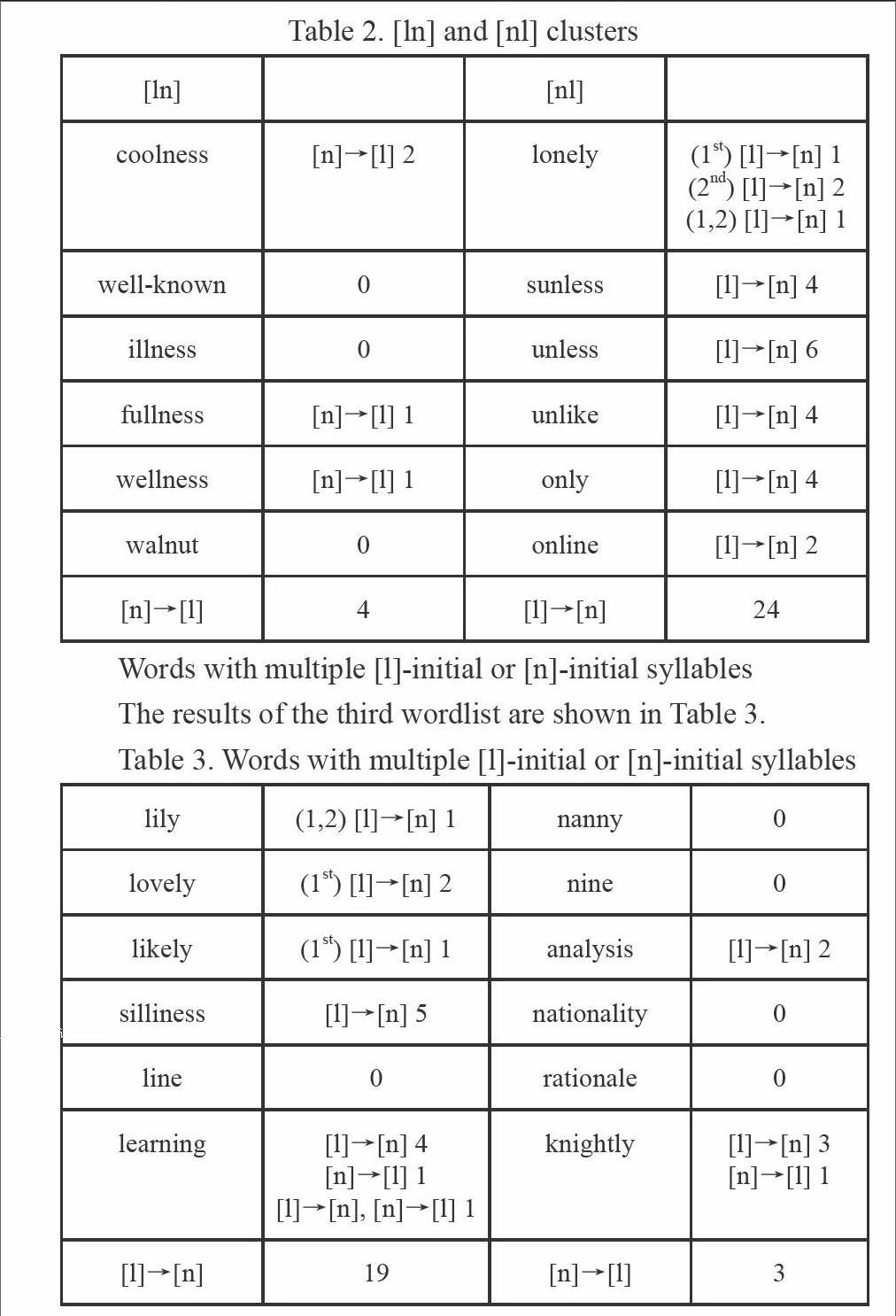

As for the second wordlist, there are mainly 2 findings. As shown in Table 2, there are 24 cases where [l] is altered into [n], whereas only 4 times for [n] into [l]. The second finding is that the alternations are progressive assimilation, namely, the sound following is changed into the sound preceding.

Words with multiple [l]-initial or [n]-initial syllables

The results of the third wordlist are shown in Table 3.

The only noticeable pattern is that alternation happens more in the direction of [l] turning into [n], which is in accordance with the previous two wordlists.

Wordlists versus Short story

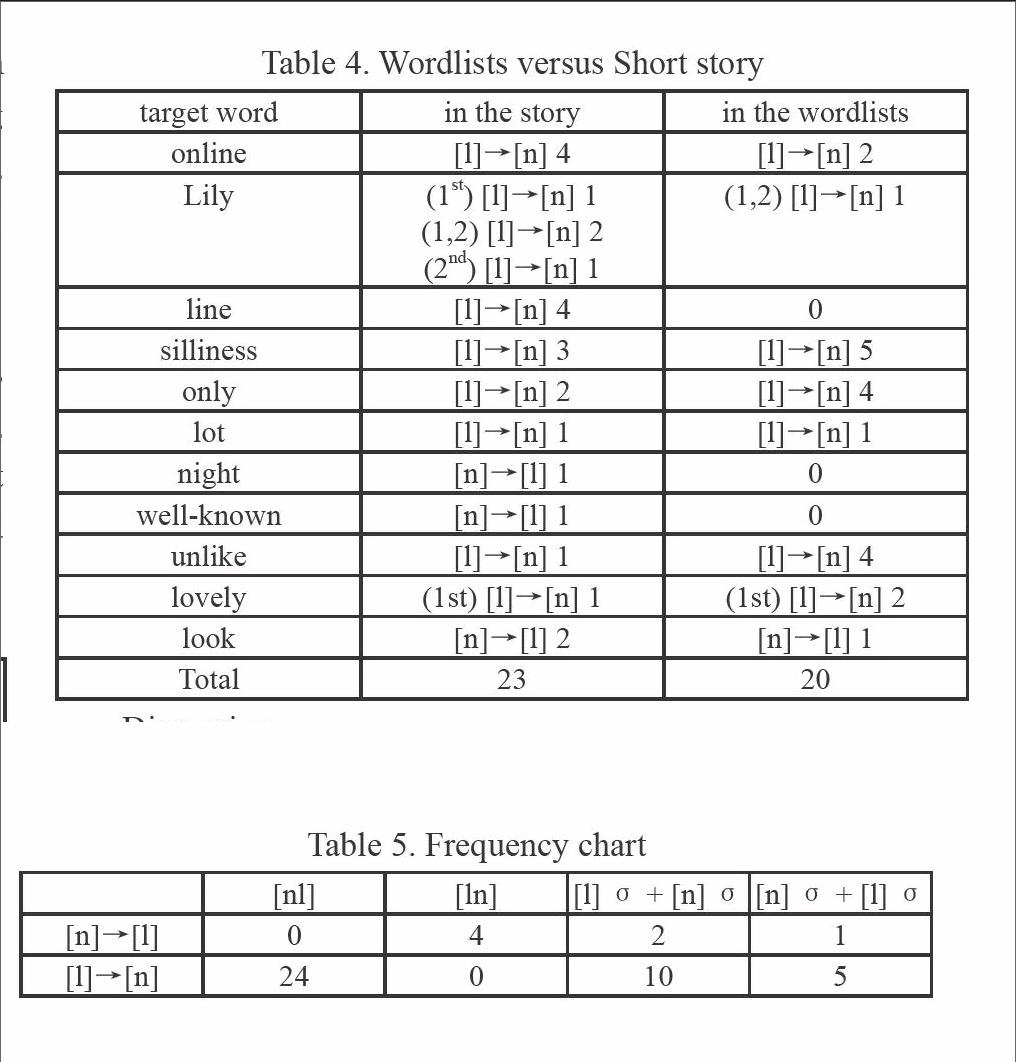

The short story is designed to test the findings from the wordlists, and it is expected to be more natural speaking. Different from the supposition, the alternation rate in the short story is only slightly higher than in the wordlists. Nevertheless, the patterns of alternation comply with the ones found from the wordlists. Namely, the alternation tends to happen from the left to the right, and from [l] to [n].

T

Discussion

The above analysis can be summarized into the following frequency chart. From the chart, we can see that the most frequent situation of [n] changing into [l] lies in [ln] clusters, followed by words that have a structure like “[l] σ + [n] σ”, then words with [n] initial syllable preceding an [l] initial syllable, but rarely in [nl] clusters. And the frequency order of [l] changing into [n] is the following: [nl] clusters, “[l] σ + [n] σ”, “[n] σ + [l] σ”, and hardly ever in [ln] clusters.

Conclusion and implications

In sum, the alternation between [l] and [n] among Sichuan English speakers is not random. In general, the chance of turning [l] into [n] is much higher than that of changing [n] into [l]. Furthermore, the phonological environment of the target sound affects alternation. Namely, the frequency of the latter sound changing into the former one far outweighs that of the opposite direction.

As an explorative study, this paper has several limitations. First, as for participants, those who have never lived in provinces other than Sichuan can be a more ideal group for research, in that the possible influence of other accents can be reduced. Also, with regards to content design, more natural speech, such as interviews or story re-narration are better choices.

References:

[1]Cukor,G.(Director).(1964).My fair lady[Video file].United States:Warner Bros.Retrieved December 1,2016.

[2]Hung,T.T.(2000).Towards a phonology of Hong Kong English.World Englishes,19(3),337-356.

[3]Ma,C.D.& Tan,L.H.(1998).‘Comparison Study of Sichuan Dialect Phonetics and English Phonetics.Journal of Sichuan Teachers College.3,11-16.

[4]Wang,W.H.(1994).‘Study of Phonetic Characteristic of Sichuan-accent Standard Mandarin.Journal of Sichuan University.3,56-61.