A systematic review of active video games on rehabilitative outcomes among older patients

Nn Zeng,Zchry Pope,Jung Eun Lee,Zn Go,*

aSchool of Kinesiolog y,University of Minnesota,Minneapolis,MN 55455,USA

bDepartment of Applied Human Sciences,University of Minnesota-Duluth,Duluth,MN 55812,USA

Review

A systematic review of active video games on rehabilitative outcomes among older patients

Nan Zenga,Zachary Popea,Jung Eun Leeb,Zan Gaoa,*

aSchool of Kinesiolog y,University of Minnesota,Minneapolis,MN 55455,USA

bDepartment of Applied Human Sciences,University of Minnesota-Duluth,Duluth,MN 55812,USA

Background:Although current research supports the use of active video games(AVGs)in rehabilitation,the evidence has yet to be systematically reviewed or synthesized.The current project systematically reviewed literature,summarized findings and evaluated the effectiveness of AVGs as a therapeutic tool in improving physical,psychological,and cognitive rehabilitative outcomes among older adults with chronic diseases.

Methods:Seven databases(Academic Search Complete,Communication&Mass Media Complete,ERIC,PsycINFO,PubMed,SPORTDiscus, and Medline)were searched for studies that evaluated the effectiveness of AVG-based rehabilitation among older patients.The initial search yielded 946 articles;after evaluating against inclusion criteria and removing duplicates,19 studies of AVG-based rehabilitation remained.

Results:Most studies were quasi-experimental in design,with physical functioning the primary outcome investigated with regard to the use of AVGs in rehabilitation.Overall,9 studies found significan improvements for all study outcomes,whereas 9 studies were mixed,with significan improvements on several study outcomes but no effects observed on other outcomes after AVG-based treatments.One study failed to fin any benefit of AVG-based rehabilitation.

Conclusion:Findings indicate AVGs have potential in rehabilitation for older patients,with several randomized clinical trials reporting positive effects on rehabilitative outcomes.However,existing evidence is insufficien to support the advantages of AVGs over standard therapy.Given the limited number of studies and concerns with study design quality,more research is warranted to make more definitve conclusions regarding the ability of AVGs to improve rehabilitative outcomes in older patients.

©2017 Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V.on behalf of Shanghai University of Sport.This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Balance;Depression;Enjoyment;Exergaming;Physical functioning;Quality of life

1.Introduction

Active video games(AVGs;also known as exergames) require players to physically interact with on-screen avatars through various physical activities(PAs)such as dancing, jogging,and boxing.1,2Given the fact that increased PA has been proven a viable approach to preventing or lessening risk of chronic diseases among a variety of populations,3,4AVGs may represent an alternative means in promoting PA participation and improving quality of life(QoL)and life satisfaction. Indeed,the positive effects ofAVGs on health-related outcomes have been reported among healthy children and youth.5–8More recently,however,AVGs have received considerable attention from researchers and health care professionals as a rehabilitative tool in clinical settings to promote individuals’physical,psychological,and cognitive functioning.9–13

1.1.Rationale

Chronic diseases like obesity,Parkinson’s disease,hypertension,arthritis,and diabetes,as well as poststroke symptoms, can force seniors to gradually abandon independent activities such as bathing,dressing,and transferring positions.14According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,chronic diseases are the leading causes of death among U.S.adults aged 65 years or older,and millions of older adults have chronic illnesses who are struggling to manage their daily symptoms.15Additionally,approximately 80%of older adults in the USA are suffering from at least 1 chronic condition,and 50%have at least 2.16As a result,chronic diseases place a significan burden on older adults because these diseases can affect an individual’sability to perform daily activities,thereby diminishing QoL. Because many of the preceding diseases often require some form of rehabilitation,some researchers and health professionals believe that AVG-based rehabilitation may increase treatment adherence and reduce treatment burden(e.g.,the need to travel to a clinic if an AVG system is set up at home)among older adults.10,11

A number of reviews with regard to AVGs have been published recently.Yet most systematic reviews on the topic were mainly focused on PA promotion and obesity prevention among healthy children and young adults.1,17,18Only a few review articles synthesized the rehabilitative effects of AVGs among rehabilitation patients and/or older adults.Specificaly,these reviews evaluated evidence regarding the rehabilitative effects of AVGs on physical outcomes,19Parkinson’s disease,20and heart failure treatment21while also investigating the safety and effica y of AVG interventions among older adults22—the population with the greatest need for rehabilitative services.Despite the need for an innovative and effective rehabilitation protocol among older adults,however,no known comprehensive review has specificaly addressed the effectiveness of AVGs on rehabilitative outcomes in this population.

1.2.Objective

Because 29%of Americans older than 50 years of age play video games,23it is important for researchers to synthesize research finding regarding the potential use of AVGs in rehabilitation programs,with the goal of providing practical implications and recommendations for health care professionals. Therefore,the purpose of this review was to systematically examine the effectiveness of AVG-based rehabilitation among older adults(≥60 years)24with chronic illnesses and/or physical impairments and propose future directions in research and rehabilitation settings utilizing this PA modality.

2.Methods

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols(PRISMA-P)2015 statement was consulted and provided the structure for this review.25

2.1.Eligibility criteria

The following inclusion criteria were used for each study: (1)published in English between January 2000 and August 2016 as peer-reviewed empirical research,(2)employed the use of at least 1 AVG(e.g.,Xbox Kinect,Wii,Dance Dance Revolution,etc.),(3)composed of older adults(mean age≥60 years)with chronic diseases and/or physical impairments(e.g., Parkinson’s disease,impaired balance,poststroke status,etc.), (4)stated that the main purpose of AVG use was for patient rehabilitation,and(5)used quantitative measures in the assessment of health-related outcomes.

2.2.Information sources and search strategies

To ensure inclusion of relevant literature,a comprehensive electronic search was conducted.The following 2-step strategy was adopted:(1)all studies relating to the topic were located using 7 databases:Academic Search Complete,Communication&Mass Media Complete,ERIC,PsycINFO,PubMed, SPORTDiscus,and Medline.Search terms used in combination were the following:“exergaming”or“active video gam*”or“wii*”and“rehabilitation”or“therapy”or“clinical”andphysical”or“cognitive”or“psychological”.Relevant studies were further identifie by means of cross-referencing the bibliographies of selected articles.

2.3.Data collection process

Three authors(NZ,ZP,ZG)screened the search results independently by evaluating the titles.If the researchers were unable to determine whether an article pertained to the topic,then the abstract was reviewed.All potential articles were downloaded as full text and stored in a shared folder,after which 3 authors (NZ,ZP,JEL)reviewed each article independently to ensure that only relevant entries were included.A list of published articles on the topic of AVGs and rehabilitation was then created in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet(Microsoft Corporation,Redmond,WA,USA).The following data were extracted: (1)year of publication and country of origin,(2)methodological details(e.g.,study design,experimental context,sample characteristics,study duration,outcome measures,AVG types, and instruments),and(3)key finding with respect to clinical effectiveness and the potential for rehabilitative outcomes(e.g., improved functional abilities,reported changes in QoL, reduced fear of falling,etc.).

2.4.Risk of bias in individual studies

Based on previous literature,1,18the risk of bias in each study was rated independently by 3 authors(NZ,ZP,JEL)using a 9-item quality assessment tool(Table 1).Items were assessed for each study as“yes”(explicitly described and present)or“no”(absent,inadequately described,or unclear).In particular, Items 1,3,4,and 8 in Table 1 were deemed the most important because these items had greater potential to significanty affect the research findings Additionally,a design quality score ranging from 0 to 9 was computed by summing up the“yes”answers.A study was considered high quality when it scored above the median after the scoring of all studies.To ensure valid scoring of the quality assessment,2 authors(NZ,JEL)independently scored each article.When incongruities occurred between the 2 authors,a third author(ZP)assessed any unresolved differences for scoring accuracy.

3.Results

3.1.Study selection

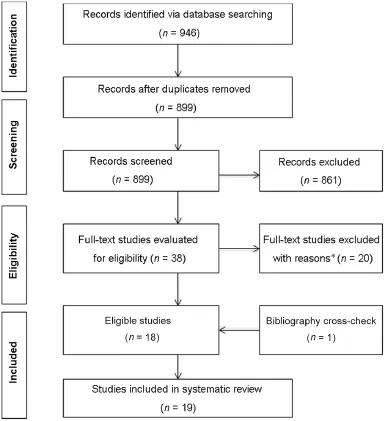

The initial search yielded 946 articles.After removing duplicates,titles and abstracts of the remaining papers were screened against the inclusion criteria.After a thorough review of the remaining papers,19 studies were included in this review (Fig.1).A high inter-rater agreement(i.e.,95%)was obtained between the authors for the articles included.

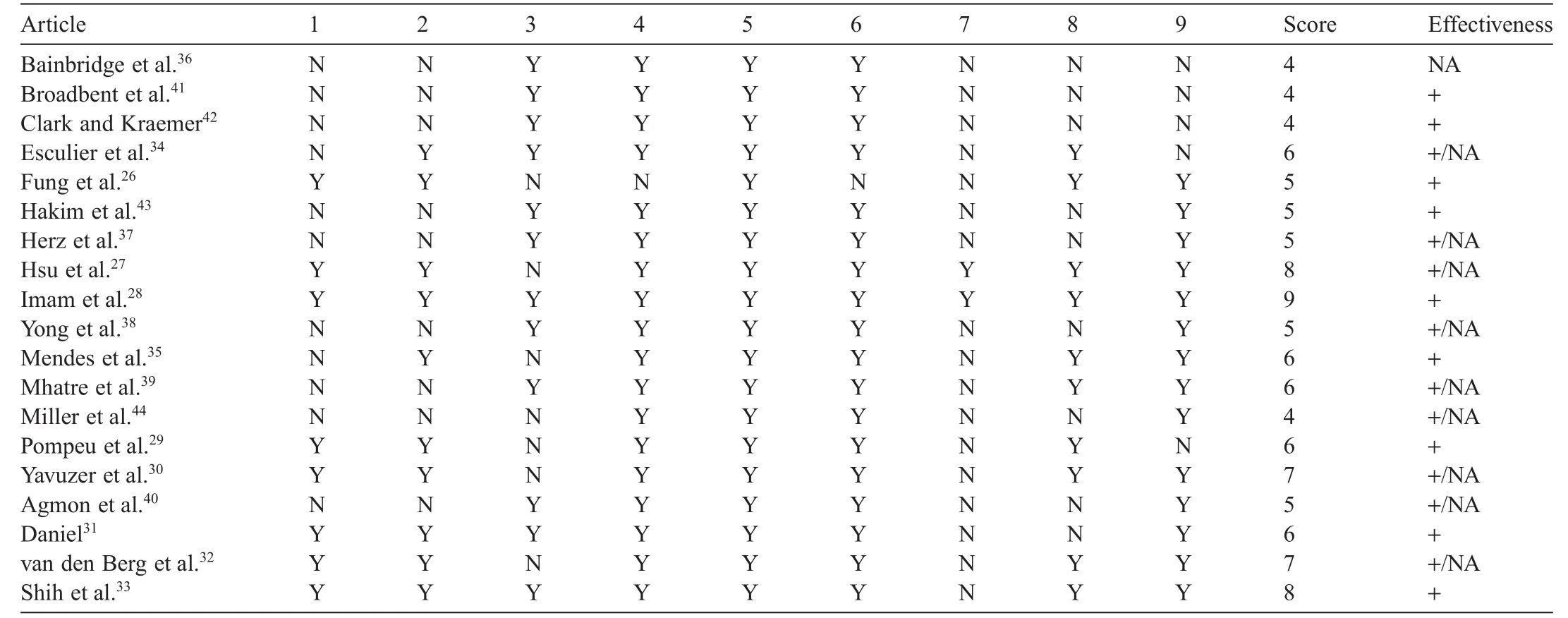

Table 1 Design quality analysis for the AVGs intervention studies.

Fig.1.Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses fl w diagram of studies through the review process.Many studies were excluded for multiple reasons.Databases included the following:Academic Search Complete(n=224),Communication&Mass Media Complete(n=9), ERIC (n=5),PsycINFO (n=114),PubMed(n=208),SPORTDiscus (n=123),and Medline(n=263).*Reasons for study exclusion included ineligible age,ineligible populations,ineligible active video game types,and ineligible outcomes.

3.2.Study characteristics

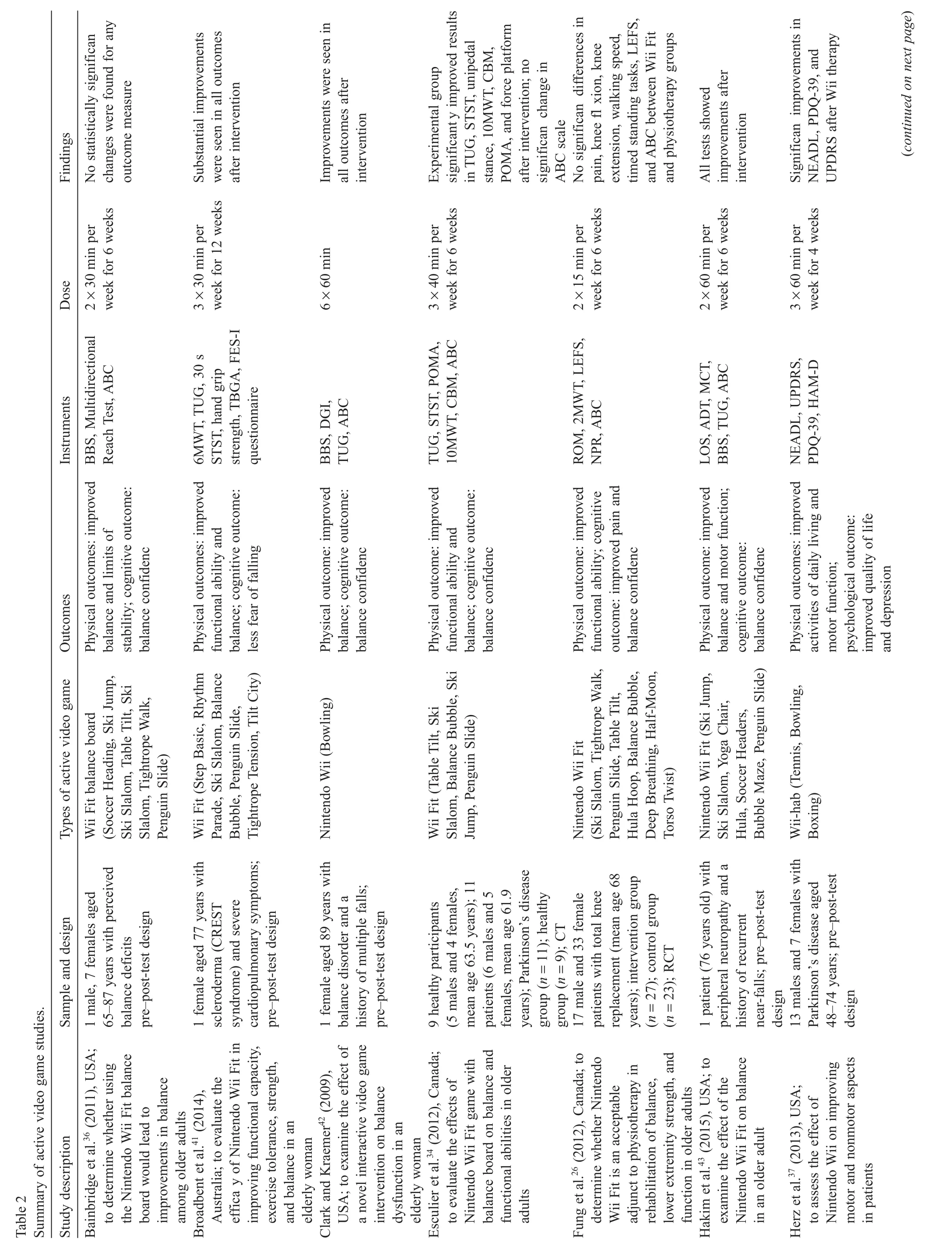

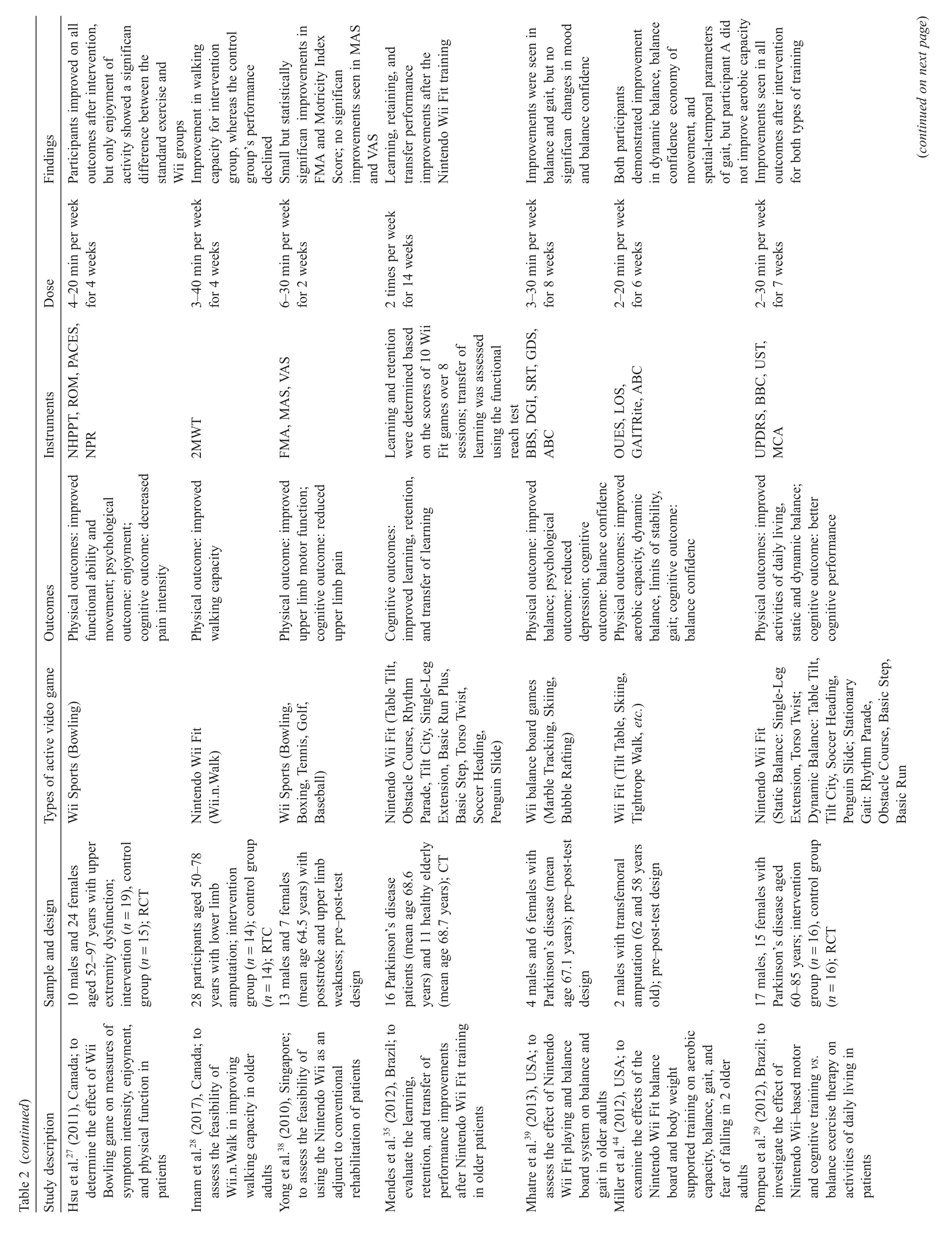

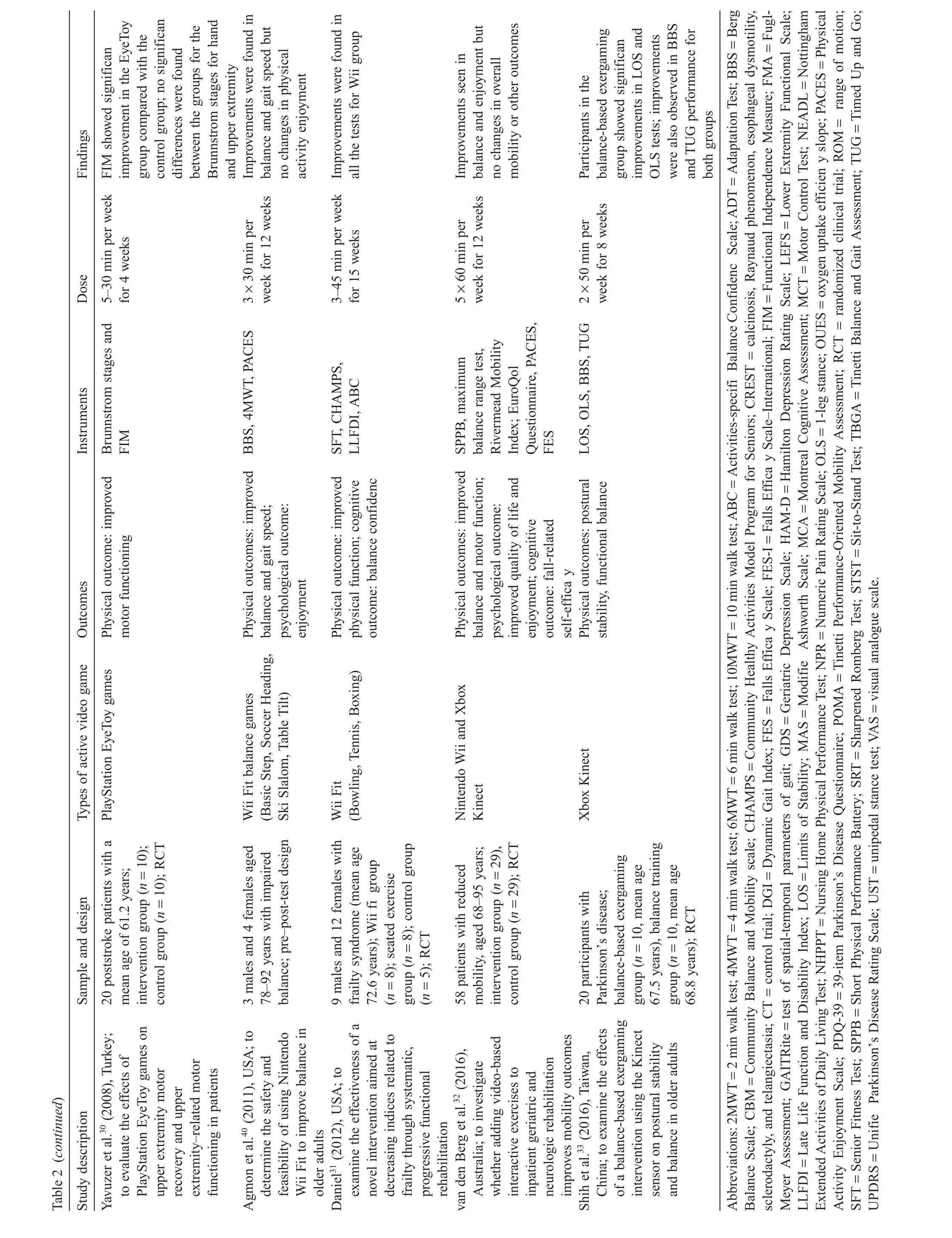

The characteristics of included studies are shown in Table 2: among the 19 studies,8 were randomized clinical trials (RCTs),26–332 were control trials(CTs;quasi-experimental pre–post-test design without randomization),34,355 were 1-group pre–post-testdesigned studies(pre-experimentaldesign with pre–post-test design among same participants),36–40and 4 were case studies(pre-experimental design with pre–post-test on 1 to 2 subjects only).41–44The USA was the primary location for AVG-based rehabilitation studies,31,36,37,39,40,42–44with 4 studies conducted in Canada,26–28,342 in Brazil29,35and Australia,32,41and 1 in Singapore,38Turkey,30and Taiwan,China,33respectively.Amajority(n=17;89%)ofthearticleswerepublished after2010,and the oldest publication was in 2008,indicating that research on AVGs and rehabilitation is a young but expanding scientifi field

Relatively large variability was seen for sample size across studies.Specificaly,the sample varied from 1 to 58 with median number of participants being 20.Intervention length ranged from 2 to 15 weeks,with the median intervention length being 6 weeks.With regard to AVG type,all studies employed commercially available AVGs.In detail,the predominant gaming consoles for rehabilitation purposes were the Nintendo Wii,Wii Fit, or a balance board(similar to the Wii Fit).Some of the games included were SoccerHeading,SkiSlalom,SkiJump,Table Tilt, Penguin Slide,Balance Bubble,and Bowling.Most often,the chronic conditions and/or impairments treated with AVG-based rehabilitation included Parkinson’s disease,29,33–35,37,39general impaired balance,36,40,42,43post-stroke status,30,38upper and lower extremity motor deficiencies27,28frailty syndrome,31postknee replacement status,26transfemoral amputation,44reducedmobility,32and scleroderma and severe cardiopulmonary symptoms.41

?

?

?

3.3.Data items

The included studies measured several variables with diverse instruments.We categorized these variables as physical, psychological,and cognitive rehabilitative outcomes.The physical outcomes included but were not limited to static and dynamic balance,gait speed,motor functioning,functional capacity,mobility,upper and lower extremity movement, strength,and aerobic capacity.Studies that investigated the effectiveness of AVG-based rehabilitation on patients’psychological and cognitive outcomes were relatively scarce compared with studies assessing physical outcomes.In this review,psychological and cognitive outcome variables included exercise enjoyment,QoL,depression,balance confidence fear of falling,pain intensity,and cognitive performance.

3.4.Risk of bias within studies

Risk of bias assessments for included studies is presented in Table 1.In detail,8 studies used a randomized design allowing for comparison between the intervention and control/ comparison groups as well as measured outcome variables before and after the intervention.Twelve studies utilized isolated AVGs for rehabilitative purposes(i.e.,no therapy other than AVGs).All the studies succeeded in retaining at least 70% of the participants and in statistically comparing groups at baseline on key outcome variables.Furthermore,2 studies described how the missing data were accounted for in the statistical analyses,with power calculations for appropriate sample sizes presented in 10 studies.Finally,numerous validated measures were used in 14 studies.

3.5.Quality assessment and effectiveness of AVG-based rehabilitation

In this review,all the included studies were AVG-based interventions.The design quality of the studies ranged from 4 to 9 (Table 1).Ten studieswere rated abovethe median score of5 and were subsequently considered high quality.Notably,of the 9 lower-quality studies,5 werescored asbeing equalto the median score and 4 scored below the median—all of which were case reports.Because the quality of research designs was low among the literature on this topic,a meta-analysis was prohibited.

Concerning the effectiveness ofAVG-based interventions on older patients’rehabilitative outcomes,9 studies found signifi cant improvements for all the outcome measures investigated, such as functional ability,walking capacity,balance confidence and cognitive performance.26,28,29,31,33,35,41–43Nine studies had mixed findings observing remarkable enhancements on several variables(e.g.,balance,fear of falling,mobility,QoL,enjoyment,etc.)with no significan effects found for other outcomes (e.g.,mobility,aerobic capacity,pain intensity,depression,etc.) after AVG-based treatments.27,30,32,34,37–40,44In particular,1 AVG study failed to produce any beneficia rehabilitative outcomes (e.g.,balance,limits of stability,and balance confidence)36

3.6.Physical effects of AVGs

Studieson AVGsforolderpatientsinvestigated awiderangeof physical functioning outcomes,with a majority of the studies on the topic focusing on whether AVG-based rehabilitation has a positive effecton balance.Indeed,11 studiesexamined the use of AVGs on static and dynamic balance ability,with 10 studies indicating that AVG-based rehabilitation could improve balance performance.Specificaly,6 pre-experimental studies demonstrated improved balance scores afterAVG therapy as follows:in Study 1,Timed Up and Go(TUG)test decreased by 0.9 s and Tinetii Balance and Gait Assessment increased by 5.5 units;41in Study 2,Berg Balance Scale(BBS)increased by 5 units,Dynamic Gait Index(DGI)increased by 2 units,and TUG decreased by 4.4 s;42in Study 3,Limits of Stability(LOS)increased by 22%, Adaptation Test(ADT)improved for downward platform rotations,TUGdecreased by 4.0 s,and BBS increased by 6 units;43in Study 4,DGI increased by 2.8 units,BBS increased by 3.3 units, and Sharpened Romberg Test(SRT)increased by 6.85 units;39in Study 5,LOS participants A and B improved by 20%and 2%, respectively;44and in Study 6,BBS increased by 5 units.40In particular,4 experimental studies also found positive results.The firs study had a CTdesign and observed significan improvements for AVG groups on the Community Balance and Mobility scale (CMB)(increased by 15 units,p<0.001)and TUG(decreased 1.9 s,p<0.04).34(Thepvalues represent comparisons between AVG-based rehabilitation and comparison/control groups.)The other3 studieswere RCTs,indicating substantialbalance changes on(1)the BBS(increased by 1.3 units,p<0.005)and unipedal stance test(UST)(improved by 7.7 units with eyes open,p<0.001;improved by 1.1 units with eyes closed,p<0.005);29(2)maximalbalancerange(improved 38 mm,p<0.05);32and(3) LOS(reaction time decreased by 0.22 s,p<0.001;endpoint excursion and directionalcontrolimproved by 4.8%,p<0.04,and 3.2%,p<0.02,respectively),1-leg stance(OLS)(less affected with eyes closed increased by 2.75 s,p<0.002),BBS(increased by 2.3 units),and TUG(decreased by 0.8 s)33as compared with control/comparison groups after AVG-based rehabilitation. Finally,1 study failed to fin balance change after an AVG-based rehabilitation program.36

As previously mentioned,studies in this review evaluated diverse physical outcomes,making it difficul to classify each outcome variable into a specifi category.In this review,14 studies examined other components of physical functioning besides balance.Among these nonbalance studies,4 of 7 nonexperimental studies indicated substantial improvements in the 6 min walk test(increased by 100 m),30 s Sit-to-Stand Test (STST)(increased 2 repetitions),hand grip strength(right increased by 2 kg,left increased by 1 kg),41motor control test (improved for amplitude with forward translations),43Nottingham Extended Activities of Daily Living Test(NEADL) (overall score decreased),unifie Parkinson Disease Rating Scale(UPDRS)(overall motor score decreased),37and 4 m walk test(4MWT)(speed increased 0.29 m/s)40after the AVG-based rehabilitation.Conversely,2 other studies showed no significan changes in oxygen uptake efficien y slope44and overall mobility after intervention.32In particular,although enhancementswere observed in Fugl-MeyerAssessment(FMA)(increased by 5.0 units)and Motricity Index(increased by 0.6 units),the study failed to improve performance on the Modifie Ashworth Scale (MAS).38In addition,7 studies comparing AVG-based rehabilitation with other treatment protocols observed comparable or equal improvements in several outcomes.In detail,1 CT found significan improvementsforAVGgroupsin STST(increased by 7.5 units,p<0.01),10 m walk test(10MWT)(decreased by 0.7 s,p<0.001),and Tinetti Performance-Oriented Mobility Assessment(POMA)(increased by 4 units,p<0.05).34Moreover,4 of6 RCTsobserved significan changesin 2 min walk test (2MWT)(increased by 7.4 units,p<0.05),28UPDRS(increased 1.2 units,p<0.001),29FunctionalIndependence Measure(FIM) (decreased 3.7 units,p=0.018),30Senior Fitness Test(SFT) (overallscoresincreased),Community Healthy Activities Model Program forSeniors(CHAMPS)(increased by 3598 kcal/week), and Late Life Function and Disability Instrument(LLFDI) (overall scores decreased)31as compared with the control/ comparison groups.Notably,the 2 other RCTs indicated no significan differencesin active range ofknee motion(p=0.22), 2MWT(p=0.855),Lower Extremity Functional Scale(LEFS) (p=0.289),26and Nursing Home Physical Performance Test (NHPPT)(p=0.299)27between AVG-based rehabilitation and conventionaltherapy—providing evidence thatAVGsmightbest be utilized as an adjunctive therapy to standard treatment.

3.7.Psychological effects of AVGs

In this review,studies investigating psychological rehabilitative outcomes were few but included assessment of enjoyment,QoL,and depression.Specificaly,3 articles investigated enjoyment in relation to AVG-based rehabilitation,with 2 RTCs indicating a positive effect on Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale(p=0.01427;p<0.0532for AVG groups after AVG intervention in relation to the comparison groups),whereas another nonexperimental study40reported the opposite.Interestingly,2 nonexperimental studies seem to suggest thatAVGs could be an effective rehabilitative tool in improving QoL,but not to a degree sufficien to trigger changes in mood.37,39Conversely,1 RCT stated that no significan change was found for the Wii group in QoL despite a slight upward trend indicating improvement after AVG-based treatment(p>0.05).32

3.8.Cognitive effects of AVGs

Because most studies on the use of AVGs to improve older patients’rehabilitative outcomes mainly concentrated on physicalfunctioning,thisactivity modality’seffectivenessin promoting cognitive rehabilitative outcomes was rarely investigated. Although 14 studies examined patients’cognitive function,10 studies were concerned with balance confidence Generally, finding were equivocal for balance confidence with 4 case studies41–44and 1 RCT31indicating improvements,whereas 2 nonexperimental studies,36,391 CT,34and 2 RCTs26,32observed no changes after AVG-based rehabilitation as compared with control/comparison groups.In this review,other cognitive rehabilitative outcomesincluded pain intensity and cognitive performance.Specificaly,1 nonexperimental study38and 1 RCT27demonstrated that AVGs were not effective for upper extremity pain management after an AVG intervention,whereas another RCT26revealed no significan difference in lowerextremity pain between an AVGgroup and a physiotherapy group.Finally,1 CT demonstrated significanty improved cognitive performance for Wii groups for attention(p=0.003)and decision-making (p=0.02),35and 1 RCT indicated significan improvements in executive function,naming,memory,orientation,etc.(overall Montreal Cognitive Assessment(MCA),p<0.001)29vs.the comparison group.

4.Discussion

The purpose of the current review was to provide a synthesis of the current evidence regarding AVG-based rehabilitation in the treatment of chronic diseases and/or impairments in older adults.The fina analysis included 19 studies.Given the limited number of included studies,as well as the high proportion of pre-experimental designs employed(n=9,47%),more highquality studies are warranted prior to drawing conclusions regarding the effectiveness of AVGs as a rehabilitative tool in older patients.

4.1.Summary of evidence

It appears that AVGs are effective in improving the overall balance abilities of older patients.However,some limitations within the included studies make discerning the overall consensus among the literature difficult First,although 6 low-quality nonexperimental design studies demonstrated balance improvementsafterAVG-based rehabilitation,4 ofthese did notindicate whether the improvements were statistically significant41–44Without providing the inferential statistics,it is hard to discern the effectiveness of AVG-based interventions on balance abilities.Second,as a result of the large number of pre-experimental designs employed,evidence of the effectiveness of AVG-based treatment cannot be surmised given the absence of a control group and the inability to monitor a patient’s PA outside the intervention.39–44Third,only 3 RCTs indicated a positive effect ofAVGs on overall balance,with 1 study employing AVG-based rehabilitation in combination with traditional therapy,making it difficul to isolate any additive effects of the AVG-based rehabilitation beyond usualcare.29Nevertheless,based on the present literature,AVGs either have a null or a positive impact on older patients’balance abilities.Thus,the overall finding tend to be positive,generally indicating thatasAVGplay increases,balance abilities may also increase.As such,AVG-based rehabilitation showsgreatpromise asan effective modality in promoting older patients’balance abilities.

Overall,moststudiesindicated thatAVG-based rehabilitation had positiveeffectson physicalfunctioning.However,given that half the studies(7 of 14)were pre-or quasi-experimental designs,a conclusion concerning the effects of AVG rehabilitation on patients’nonbalance physical functioning cannot be drawn from these non-RCTs.Even though the majority of RCTs reported favorable results,the limited number of publications and the use of different instruments measuring dissimilar physical outcomes made it challenging to compare each study anddraw a definit conclusion regarding the effects of AVG-based rehabilitation on specifi physical functions.Additionally, because a couple of RCTs28,31were designed as feasibility trails, with the primary goal to assess the feasibility of AVG-based rehabilitation as opposed to drawing conclusions regarding the effica y of this treatment modality,the results cannot readily be interpreted to suggest that AVG-based intervention is more effective than usual care.Finally,a generalized conclusion must be regarded with caution because the reviewed studies had a wide range of sample sizes and relatively short intervention durations,which may limit the generalizability and practical implicationsofthe findings Despite these mixed findings based on our examination of the literature,there appears to be an emphasis on positive results.That is,beneficia physical outcomes from AVG-based rehabilitation are possible.Mostimportant,negative effects of AVGs on physical functioning were not reported.

One advantage of AVG-based rehabilitation over conventional physical therapy is that this modality not only provides physical benefit but also acts as a form of entertainment.The most appealing aspect of AVGs lies in the activity’s motivating features.1,45That is,AVGs offer players a much higher level of engagement,which can significanty reduce the level of perceived exertion in players.46As a result,the levelofmotivation to stick with the activity is also much higher than with traditional rehabilitation.In this sense,players may improve enjoyment during AVG gameplay leading to potentially reduced depression as well as increased QoL over time and,more important,sustained participation in AVG-based rehabilitation activities.In general,evidence ofthe effectivenessofAVGson psychological rehabilitative outcomes is favorable,with some studies indicating positive effects but others reporting no effect.The finding were inconsistent,with previous studies indicating positive psychological effects ofAVGs on enjoyment and depression among healthy youth and adults.47,48Notably,extrinsic factorswithin the included studies may have affected the results owing to the high proportion of participants with pre-existing depression.39Additionally,it is possible that the intensity and length ofAVG-based rehabilitation were not high enough to elicit changes in mood (e.g.,3×60 min perweek for4 weeks37vs.3×30 min perweek for8 weeks39).Finally,itisalso likely thatsome participantshad previous experience playing AVGs,leading to low stimulation across the patients during the treatment.As a result,the patients may have had differing perspectives regarding the effectiveness ofAVG-based rehabilitation on psychological outcomes.Meanwhile,because modern technology is not part of daily life for many seniors,with many ofthem being unfamiliarwith technology,the motivation to learn how to use AVGs is rather weak because the learning process may be frustrating for many older adults—particularly among older patients already burdened enough by treatments related to their diseases and/or impairments.Nevertheless,AVG-based rehabilitation still has huge potential to generate psychological benefit among seniors with chronic diseases.

At this point,it is unclear whether AVGs are a viable rehabilitative tool to improve cognitive outcomes in older patients. First,as previously stated,despite finding demonstrating improved balance confidenc postintervention,studies did not indicate whether these improvements were statistically significant31,41–44Without providing inferential statistics,we cannot conclude that AVG-based rehabilitation is effective for balance confidence Second,most current studies have examined the acute effects of AVG-based rehabilitation without follow-ups to assess the sustainability of intervention adaptations,which might cause researchers to under-or over-rate the potential of AVGs and result in inaccurate conclusions regarding the effectiveness of AVGs on patients’cognitive outcomes. Additionally,because individuals with higher education levels and/or socioeconomic status may possess greater cognitive ability than individuals of lower education levels and/or socioeconomic status,49some factors such as education,occupation, and even personality could have affected individuals’cognitive performance within those studies.Finally,the nature of AVGs could be a confounding factor influencin intervention results because some types of AVGs(e.g.,games that require more executive functions)may have a stronger cognitive demand than others.In this regard,patients may receive varying stimulation intensities from differentAVG-based treatments,leading to different results in cognitive rehabilitative outcomes.Therefore, we cannot yet conclude whetherAVG-based rehabilitation has a positive effect on older patients’cognitive outcomes.Indeed, PA likely influence multiple pathways including physiological, neurologic,psychological,and even social factors,50which may result in improved cognitive function.Physiologically,regular PA has been proven effective in promoting brain function,51and neuroelectric measures have shown improved cognitive control and attention after acute and chronic PA.52That said,as one type of PA,AVGs hold great promise to improve older adults’cognitive outcomes.

4.2.Limitations and recommendations

Although the current study’s strength lies in the provision of the firs known synthesis of the effects of AVG-based rehabilitation in older patients in a systematic manner,the study is not without limitations.To begin,the current review is limited by the inclusion of only peer-reviewed full-text and English language publications despite the fact other unpublished and non-English work may be available on the topic.Second,qualitative perspectives such as user experience were not included in this review because they fell outside the review’s primary objective.However,these viewpoints would have important relevance for long-term engagement in AVG-based rehabilitation.Third,the heterogeneity of samples,outcomes,interventions,effects,measurement instruments,and research designs lessened the power to detect significan differences and summarize overall significan findings Finally,the variety of AVGs employed in these intervention studies limited the ability to discern which specifi games,and which aspects of those games,are most useful for rehabilitation of specifi diseases and/or impairments.

To better evaluate the effects ofAVG-based rehabilitation on older patients,future studies should continue to determine guidelines regarding the ideal dose(i.e.,AVG-based interventions’intensity,duration,and frequency)of AVG gameplayamong older adults with specifi diseases and/or impairments. This could be achieved via the use of more high-quality study designs (i.e.,RCTs or quasi-experimental pre–post-test designed studies)and more follow-up testing with patients to discern the sustainability of the adaptations stimulated by certain durations and frequencies of AVG-based rehabilitation. Second,researchers may want to isolate AVG-based rehabilitation and standard therapy procedures during rehabilitation with older patients.Isolating these treatments will allow for better examination of the stand-alone benefit that AVG-based rehabilitation may have in comparison with standard therapy.Third, researchers may want to integrate newer technology,such as the Microsoft Xbox Kinect,and employ multiple types of AVGs to distinguish and surmise the effectiveness of specifi AVGs on specifi diseases and/or impairments.

5.Conclusion

Researchers have made considerable progress in examining the effectiveness of AVG-based rehabilitation among older adults with chronic diseases.Although finding are generally positive(i.e.,demonstrating improvements in clinical outcomes as a result ofAVG-based rehabilitation compared with standard therapy or no difference between AVG-based rehabilitation and standard therapy),finding are still inconsistent.Indeed,AVGs showed potential as rehabilitative tools among older patients, with several RCTs indicating thatAVG-based rehabilitation had positive effects on some aspects of physical,psychological,and cognitive functioning.Notably,little to no evidence suggesting that AVGs had a negative impact on any outcomes was documented.That is,beneficia rehabilitative outcomes from AVG-based rehabilitation are possible.However,the limited number of available RCTs and concerns with design quality of other non-RCTs restrict the ability to provide definitve conclusions supporting the possible advantages ofAVG-based rehabilitation over standard therapy.Owing to limitations present in the current literature,the effectiveness ofAVGs in clinical rehabilitation settings might have been under-or overestimated,with more research warranted to make more definitve conclusions regarding the value ofAVG-based rehabilitation in the improvement of rehabilitative outcomes in older patients.Nonetheless, researchers and health care professionals should continue to explore the rehabilitation benefit of AVGs and harness the potential of AVGs to motivate patients in a trustworthy manner.

Authors’contributions

NZ carried out the study,performed the data sorting and analysis,and drafted the manuscript;ZP performed the data sorting and analysis and helped draft the manuscript;JEL performed the data sorting and analysis and helped draft the manuscript;ZG conceived of the study,retrieved papers,and helped draft the manuscript.All authors have read and approved the fina version of the manuscript,and agree with the order of presentation of the authors.

Competing interests

None of the authors declare competing financia interests.

1.Gao Z,Chen S.Are field-base exergames useful in preventing childhood obesity?A systematic review.Obes Rev 2014;15:676–91.

2.Gao Z,Podlog L,Huang C.Associations among children’s situational motivation,physical activity participation,and enjoyment in an active dance video game.J Sport Health Sci 2013;2:122–8.

3.Herring MP,Puetz TW,O’Connor PJ,Dishman RK.Effect of exercise training on depressive symptoms among patients with a chronic illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:101–11.

4.Nelson ME,Rejeski WJ,Blair SN,Duncan PW,Judge JO,King AC,et al. Physical activity and public health in older adults:recommendation from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association.Med Sci Sports Exerc 2007;39:1435–45.

5.Daley AJ.Can exergaming contribute to improving physical activity levels and health outcomes in children?Pediatrics 2009;124:763–71.

6.Garn AC,Baker BL,Beasley EK,Solmon MA.What are the benefit of a commercial exergaming platform for college students?Examining physical activity,enjoyment,and future intentions.J Phys Act Health 2012;9:311–8.

7.Gao Z,Hannan P,Xiang P,Stodden DF,Valdez VE.Video game-based exercise,Latino children’s physical health,and academic achievement.Am J Prev Med 2013;44:240–6.

8.Sun H.Operationalizing physical literacy:the potential of active video games.J Sport Health Sci 2015;4:145–9.

9.Saposnik G,Teasell R,Mamdani M,Hall J,McIlroy W,Cheung D,et al. Effectiveness of virtual reality using Wii gaming technology in stroke rehabilitation:a pilot randomized clinical trial and proof of principle. Stroke 2010;41:1477–84.

10.Bieryla KA,Dold NM.Feasibility of Wii Fit training to improve clinical measures of balance in older adults.Clin Interv Aging 2013;8:775–81.

11.Gioftsidou A,Vernadakis N,Malliou P,Batzios S,Sofokleous P,Antoniou P,et al.Typical balance exercises or exergames for balance improvement? J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil 2013;26:299–305.

12.Hung JW,Chou CX,Hsieh YW,Wu WC,Yu MY,Chen PC,et al. Randomized comparison trial of balance training by using exergaming and conventional weight-shift therapy in patients with chronic stroke.Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2014;95:1629–37.

13.Toulotte C,Toursel C,Olivier N.Wii Fit training vs.adapted physical activities:which one is the most appropriate to improve the balance of independent senior subjects?A randomized controlled study.Clin Rehabil 2012;26:827–35.

14.National Council on Aging.Chronic disease management.Available at: https://www.ncoa.org/healthy-aging/chronic-disease/; 2012 [accessed 03.01.2016].

15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.The state of aging and health in America.Available at:https://www.ncoa.org/healthy-aging/chronic disease/;2013[accessed 03.01.2016].

16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.Disaster preparedness and the chronic disease needs of vulnerable older adults.Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2008/jan/07_0135.htm;2008 [accessed 03.01.2016].

17.Lamboglia CM,da Silva VT,de Vasconcelos Filho JE,Pinheiro MH, Munguba MC,Silva Júnior FV,et al.Exergaming as a strategic tool in the figh against childhood obesity:a systematic review.J Obes 2013;2013:1–8.

18.Peng W,Crouse JC,Lin JH.Using active video games for physical activity promotion:a systematic review of the current state of research.Health Educ Behav 2013;40:171–92.

19.Staiano AE,Flynn R.Therapeutic uses of active videogames:a systematic review.Games Health J 2014;3:351–65.

20.Barry G,Galna B,Rochester L.The role of exergaming in Parkinson’s disease rehabilitation:a systematic review of the evidence.J Neuroeng Rehabil 2014;11:33.doi:10.1186/1743-0003-11-33

21.Verheijden Klompstra L,Jaarsma T,Strömberg A.Exergaming in older adults:a scoping review and implementation potential for patients with heart failure.Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2014;13:388–98.

22.Skjæret N,Nawaz A,Morat T,Schoene D,Helbostad JL,Vereijken B. Exercise and rehabilitation delivered through exergames in older adults:an integrative review of technologies,safety and effica y.Int J Med Inform 2016;85:1–16.

23.Entertainment Software Association.Essential facts about the computer and video game industry.Available at:http://www.theesa.com/wp-content/ uploads/2015/04/ESA-Essential-Facts-2015.pdf;2015 [accessed 03.01 .2016].

24.World Health Organization.Definitio of an older or elderly person. Available at:http://www.who.int/healthinfo/survey/ageingdefnolder/en/; 2002[accessed 25.08.2016].

25.Moher D,Shamseer L,Clarke M,Ghersi D,Liberati A,Petticrew M,et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols(PRISMA-P)2015 statement.Syst Rev 2015;4:1.doi:10.1186/ 2046-4053-4-1

26.Fung V,Ho A,Shaffer J,Chung E,Gomez M.Use of Nintendo Wii Fit in the rehabilitation of outpatients following total knee replacement: a preliminary randomized controlled trial.Physiotherapy 2012;98:183–8.

27.Hsu JK,Thibodeau R,Wong SJ,Zukiwsky D,Cecile S,Walton DM.A“Wii”bit of fun:the effects of adding Nintendo Wii Bowling to a standard exercise regimen for residents of long-term care with upper extremity dysfunction.Physiother Theory Pract 2011;27:185–93.

28.Imam B,Miller WC,Finlayson H,Eng JJ,Jarus T.A randomized controlled trial to evaluate the feasibility of the Wii Fit for improving walking in older adults with lower limb amputation.Clin Rehabil 2017;31:82–92.

29.Pompeu JE,Mendes FA,Silva KG,Lobo AM,Oliveira Tde P,Zomignani AP,et al.Effect of Nintendo Wii-based motor and cognitive training on activities of daily living in patients with Parkinson’s disease:a randomized clinical trial.Physiotherapy 2012;98:196–204.

30.Yavuzer G,Senel A,Atay MB,Stam HJ.‘PlayStation EyeToy games’’improve upper extremity-related motor functioning in subacute stroke: a randomized controlled clinical trial.Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2008;44: 237–44.

31.Daniel K.Wii-hab for pre-frail older adults.Rehabil Nurs 2012;37:195–201.

32.van den Berg M,Sherrington C,Killington M,Smith S,Bongers B,Hassett L,et al.Video and computer-based interactive exercises are safe and improve task-specifi balance in geriatric and neurological rehabilitation: a randomized trial.J Physiother 2016;62:20–8.

33.Shih MC,Wang RY,Cheng SJ,Yang YR.Effects of a balance-based exergaming intervention using the Kinect sensor on posture stability in individuals with Parkinson’s disease:a single-blinded randomized controlled trial.J Neuroeng Rehabil 2016;13:78.doi:10.1186/s12984-016-0185-y

34.Esculier JF,Vaudrin J,Bériault P,Gagnon K,Tremblay LE.Home-based balance training programme using Wii Fit with balance board for Parkinson’s disease:a pilot study.J Rehabil Med 2012;44:144–50.

35.Mendes FADS,Pompeu JE,Lobo AM,da Silva KG,Oliveira TDP, Zomignani AP,et al.Motor learning,retention and transfer after virtual-reality–based training in Parkinson’s disease—effect of motor and cognitive demands of games:a longitudinal,controlled clinical study. Physiotherapy 2012;98:217–23.

36.Bainbridge E,Bevans S,Keeley B,OrielK.The effectsof the Nintendo Wii Fit on community-dwelling older adults with perceived balance deficits a pilot study.Phys Occup Ther Geriatr 2011;29:126–35.

37.Herz NB,Mehta SH,Sethi KD,Jackson P,Hall P,Morgan JC.Nintendo Wii rehabilitation(“Wii-hab”)provides benefit in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2013;19:1039–42.

38.Yong JL,Yin TS,Xu D,Thia E,Chia PF,Kuah CW,et al.A feasibility study using interactive commercial off-the-shelf computer gaming in upper limb rehabilitation in patients after stroke.J Rehabil Med 2010;42:437–41.

39.Mhatre PV,Vilares I,Stibb SM,Albert MV,Pickering L,Marciniak CM, et al.Wii Fit balance board playing improves balance and gait in Parkinson disease.PM R 2013;5:769–77.

40.Agmon M,Perry CK,Phelan E,Demiris G,Nguyen HQ.A pilot study of Wii Fit exergames to improve balance in older adults.J Geriatr Phys Ther 2011;34:161–7.

41.Broadbent S,Crowley-McHattan Z,Zhou S.The effect of the Nintendo Wii Fit on exercise capacity and gait in an elderly woman with CREST syndrome.Int J Ther Rehabil 2014;21:539–46.

42.Clark R,Kraemer T.Clinical use of Nintendo Wii bowling simulation to decrease fall risk in an elderly resident of a nursing home:a case report.J Geriatr Phys Ther 2009;32:174–80.

43.Hakim RM,Salvo CJ,Balent A,Keyasko M,McGlynn D.Case report: a balance training program using the Nintendo Wii Fit to reduce fall risk in an older adult with bilateral peripheral neuropathy.Physiother Theory Pract 2015;31:130–9.

44.Miller CA,Hayes DM,Dye K,Johnson C,Meyers J.Using the Nintendo Wii Fit and body weight support to improve aerobic capacity,balance,gait ability,and fear of falling:two case reports.J Geriatr Phys Ther 2012;35: 95–104.

45.Gao Z,Zhang T,Stodden D.Children’s physical activity levels and their psychological correlates in interactive dance versus aerobic dance.J Sport Health Sci 2013;2:146–51.

46.Gao Y,Gerling KM,Mandryk RL,Stanley KG.Decreasing sedentary behaviours in pre-adolescents using casual exergames at school.Proceedings of the fi st ACM SIGCHI Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play.ACM 2014.p.97–106.

47.Verhoeven K,Abeele VV,Gers B,Seghers J.Energy expenditure during Xbox Kinect play in early adolescents:the relationship with player mode and game enjoyment.Games Health J 2015;4:444–51.

48.Li J,Theng YL,Foo S.Effect of exergames on depression:a systematic review and meta-analysis.Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 2016;19:34–42.

49.Reed BR,Dowling M,Tomaszewski Farias S,Sonnen J,Strauss M, Schneider JA,et al.Cognitive activities during adulthood are more important than education in building reserve.J Int Neuropsychol Soc 2011;17:615–24.

50.Howie EK,Pate RR.Physical activity and academic achievement in children:a historical perspective.J Sport Health Sci 2012;1:160–9.

51.van Praag H.Neurogenesis and exercise:past and future directions. Neuromolecular Med 2008;10:128–40.

52.Mayes SD,Calhoun SL,Bixler EO,Zimmerman DN.IQ and neuro-psychological predictors of academic achievement.Learn Individ Differ 2009;19:238–41.

Received 4 July 2016;revised 2 September 2016;accepted 5 September 2016 Available online 5 December 2016

Peer review under responsibility of Shanghai University of Sport.

*Corresponding author.

E-mail address:gaoz@umn.edu(Z.Gao)

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2016.12.002

2095-2546/©2017 Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V.on behalf of Shanghai University of Sport.This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Journal of Sport and Health Science2017年1期

Journal of Sport and Health Science2017年1期

- Journal of Sport and Health Science的其它文章

- Building a healthy China by enhancing physical activity: Priorities,challenges,and strategies

- Exercise is...?:A commentary response

- Exergaming:Hope for future physical activity?or blight on mankind?

- Running slow or running fast;that is the question: The merits of high-intensity interval training

- Fairness in Olympic sports:How can we control the increasing complexity of doping use in high performance sports?☆

- Fight fir with fire Promoting physical activity and health through active video games