Work-up and management of a high-risk patient with primary central nervous system lymphoma

Pervin A. Zeynalova, Gayane S. Tumyan, Mikhail B. Dolgushin, Mobil I. Akhmedov

1Division of Hematology and Bone Marrow Transplantation;2Department of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging, N.N. Blokhin Russian Cancer Research Center, Moscow 115478, Russia

CASE REPORT

Work-up and management of a high-risk patient with primary central nervous system lymphoma

Pervin A. Zeynalova1, Gayane S. Tumyan1, Mikhail B. Dolgushin2, Mobil I. Akhmedov1

1Division of Hematology and Bone Marrow Transplantation;2Department of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging, N.N. Blokhin Russian Cancer Research Center, Moscow 115478, Russia

Primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) is a rare disorder that, in 95% of cases, represents diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. As such, making an accurate diagnosis is important. At present, stereotactic-guided biopsy is a recognized method of choice for tissue analysis. However, the diagnostic work-up for high-risk patients is determined by their performance status. Here, we report a case of PCNSL in a high-risk patient, for whom diagnosis was established by cerebrospinal fluid cytology and flow cytometry, which significantly shortened a diagnostic work-up period and allowed for the immediate treatment of the patient.

Brain neoplasms; CNS; lymphoma; high risk; flow cytometry; cerebrospinal fluid

Introduction

Primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) comprises all cases of lymphomas that exclusively involve the brain, spinal cord, eyes, meninges, and cranial nerves in the absence of systemic lymphoproliferative process upon diagnosis. Some registry reports declare that PCNSL represents 4% of all intracranial tumors and 4%-6% of all extranodal lymphomas (NHL)1. However, recent studies suggest that the incidence of PCNSLs, especially among the elderly is increasing2. Although the vast majority of all PCNSL cases correspond to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL)3, the World Health Organization classification considered PCNSL as a discrete entity4. Owing to the absence of typical clinical presentation, molecular biology and immunohistochemistry are important in making an accurate PCNSL diagnosis5. At present, stereotactic-guided biopsy is a recognized method of choice for tissue analysis. In this article, we report a case of primary DLBCL of the central nervous system (CNS) established by cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) flow cytometry, which extremely shortened the diagnostic work-up period.

Case report

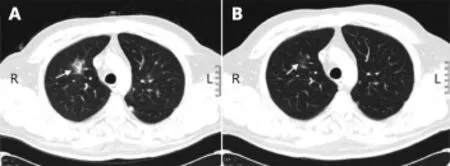

A 52-year old patient complaining double vision and ataxia was presented to the N.N. Blokhin Russian Cancer Research Center. His state of health, assessed by the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) Performance Status, corresponded to ECOG-3. The patient initially underwent PET-scanning, performed by the community-based care (Figure 1), which revealed a 2.4 cm × 1.4 cm mass in the left cerebellum hemisphere with maximal standardized uptake value (SUV) 40.67 and spinal cord FDG uptake at the Th11-S2 level with maximal SUV 13.05. Subsequent neurological examination revealed left blepharoptosis (MRD-2), facial hyposensitivity at the level of the left nervus mandibularis innervation, both side missed finger-to-nose test, and instability in the Romberg’s stance. Blood count showed leucocytosis (19.39 × 109/L). Serum test revealed an elevated LDH (610 units/L) level. Contrast-enhanced MRI in the T2, T2-flair, and DWI regimen also revealed two lesions in the left cerebellum hemisphere (Figure 2): the first was 2.8 cm × 1.6 cm in size; the second had a diameter of 1.0 cm and was located laterally to the first. Lumbar puncture was performed, and liquor analysis revealed cellularity of 1820 cells/mL, with 73% of blast cells and protein level above 1 g/L. Cytology examination of CSF demonstrated large centroblastic-type cells with high mitosis frequency, which were suspicious for lymphoma (Figure 3). Immunophenotyping of CSF (Figure 4) revealed that 55% of cellscorresponded to k-clonal CD5, CD10 - negative, CD19, CD20, CD45 - positive B-cell lymphocytes that, together with conventional cytology, indicated DLBCL. Bone marrow examination revealed no evidence of lymphoma dissemination. In the absence of testis lesions by ultrasound, peripheral lymphadenopathy and no other organ involvement, the diagnosis for PCNSL was made.

Figure 1 PET/CT scan. FDG uptake by the 2.4 cm × 1.4 cm mass in the left cerebellum hemisphere with maximal SUV 40.67 and spinal cord FDG uptake at the Th11-S2 level with max SUV 13.05.

The patient was recommended for intrathecal therapy, followed by a systemic therapy. Methotrexate (MTX) 15 mg, cytarabine (Ara-C) 40 mg, and dexametasone 4 mg were introduced intrathecally three times with a 3-day interval. Subsequent CSF analysis demonstrated cellularity decrease to 228 cells/mL, with 5% of blasts and protein level remaining above 1 g/L. Next, the patient underwent systemic chemoimmunotherapy with rituximab - 700 mg (day 0), high-dose methotrexate (HD-MTX) - 3.5 g/m2(day 1), high dose Ara-C (HD-araC) - 2 g/m2(day 1-2), dexamethasone 16 mg per day (days 1-7). After the first course control, MRI revealed a decrease of primary lesions to 1.9 cm × 1.0 cm and 0.3 cm × 0.4 cm, respectively (Figure 5). CSF analysis demonstrated cellularity of 14 cells/mL, with no blasts and protein level of 0.84 g/L. Treatment-related complications included severe cytopenia, which was corrected with transfusion of 3 red blood cells and 1 platelet packs and pulmonary aspergillus, detected by thorax computer tomography. Voriconazole (300 mg twice per day) was administered with subsequent computer tomography scanning to determine the response (Figure 6). At the time of writing this article, the patient is currently undergoing his third chemoimmunotherapy course. One more course of the same chemoimmunotherapy regimen has been planned with subsequent analysis of response.

Discussion

PCNSL is a rare disorder that strongly correlates with immunodeficiency. Although this link has already been reported, no exact mechanism has yet been identified6. Moreover, the incidence of PCNSL in immunocompetent patients is increasing7.

Figure 3 Cytology examination of CSF. Large centroblastic-type cells with high mitosis frequency are strongly suspicious for lymphoma (H&E staining, 200×).

Figure 4 Immunophenotyping of CSF. Fifty-five percent of cells correspond to k-clonal, CD5, CD10 - negative, CD19, CD20, CD45 - positive B-cell lymphocytes indicating DLBCL.

Figure 5 Control MRI. Distal (A) and proximal (B) slice demonstrating decrease of primary lesions (white arrows) to 1.9 cm × 1.0 cm and 0.3 cm × 0.4 cm, respectively.

Radiotherapy has been the only effective treatment method for patients with PCNSL for a long time. However, despite a high rate of response, radiotherapy alone provides limited survival benefit with an average overall survival (OS) duration of 10-18 months and a 5-year OS < 5%8. Owing to the disabling neurotoxicity, whole brain radiotherapy is only recommended by a few authors as consolidation in 40-45 Gy dose after HD-MTX-based chemotherapy for patients with residual disease1.

Figure 6 (A) Initial CT scan demonstrating a 3.0 cm × 2.0 cm lesion in the S10 of the right lung (white arrow) suspicious for aspergillus. (B) CT scan after treatment with voriconazole demonstrating almost total regress of the lesion (white arrow).

Chemotherapy has a key role in the PCNSL treatment. Therefore, the choice of medication and treatment should be based on whether it has a strong ability to penetrate the blood-brain barrier. Nowadays, the backbone of PCNSL treatment includes a combination of HD-araC (2 g/m2) with HD-MTX (3.5 g/m2). This recommendation is based on the results of the open randomized phase 2 study featuring a combination of HD-araC with HD-MTX, which has demonstrated significantly better complete remission rate compared with HD-MTX alone (46% against 18%)9.

Another recent randomized phase 2 International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group-32 (IELSG32) trialcompared treatment efficacy in the PCNSL patients, who were divided into three groups depending on treatment algorithm. Complete remission has been achieved in 49% of patients treated with MATRix regimen (methotrexatecytarabine-thiotepa-rituximab) compared with 23% in methotrexate-cytarabine alone and 30% in methotrexatecytarabine-rituximab regimen thus making MATRix the most preferable regimen for patients with newly diagnosed PCNSL10.

Stereotactic biopsy is the method of choice in diagnosing PCNSL and is widely recommended. However, we suggest that this recommendation should be applied only for lowrisk patients. The need for CSF analysis for patients requiring urgent treatment cannot be underestimated. According to some studies, CSF cytomorphology can detect lymphoma cells in 18% of newly diagnosed PCNSL cases11. Another report has proven that flow cytometric immunophenotyping is twice more sensitive than classic cytomorphology for diagnosing CNS localizations of hematologic malignancies (77% against 32%)12, thus demonstrating that a combination of these two methods is a strong tool in PCNSL diagnosis. Finally, the most recent systematic review of 27 studies, which compared sensitivity of flow cytometry and cytomorphology for meningeal involvement from lymphoid neoplasms, has concluded that a combination of these two methods increases the number of positive CSF samples for lymphoma involvement13.

The current study reports a case of DLBCL involving cerebellum and spinal cord in a high-risk patient. The diagnosis was made by cytology examination and the immunophenotyping of CSF, which led to the immediate start of therapy. The patient has undergone systemic and intrathecal HD-MTX-based chemoimmunotherapy with good response assessed after the first course. Based on the successful management of our patient, we assume that CSF flow cytometry and cytology combination, instead of brain biopsy, is the preferable option for patients requiring urgent treatment, because it significantly accelerates the diagnostic work-up period, allowing for the immediate therapy of the patient as soon as analysis results are made available. Additionally, this strategy is associated with reduced methodrelated complications. However, further studies including case reports are needed, because they may represent opportunities to obtain additional clinical information to support the feasibility of this approach.

Conflict of interest statement

No potential conflicts of interest are disclosed.

1.Ferreri AJM. How I treat primary CNS lymphoma. Blood. 2011; 118: 510-22.

2.Villano JL, Koshy M, Shaikh H, Dolecek TA, McCarthy BJ. Age, gender, and racial differences in incidence and survival in primary CNS lymphoma. Br J Cancer. 2011; 105: 1414-8.

3.Camilleri-Broët S, Martin A, Moreau A, Angonin R, Hénin D, Gontier MF, et al. Primary central nervous system lymphomas in 72 immunocompetent patients: pathologic findings and clinical correlations. Groupe Ouest Est d'étude des Leucénies et Autres Maladies du Sang (GOELAMS). Am J Clin Pathol. 1998; 110: 607-12.

4.Campo E, Swerdlow SH, Harris NL, Pileri S, Stein H, Jaffe ES. The 2008 WHO classification of lymphoid neoplasms and beyond: evolving concepts and practical applications. Blood. 2011; 117: 5019-32.

5.Chen D, Gu W, Li W, Liu X, Yang X. Primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the central nervous system: a case report and literature review. Oncol Lett. 2016; 11: 3085-90.

6.Ferreri AJM, Marturano E. Primary CNS lymphoma. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2012; 25: 119-30.

7.Mrugala MM, Rubenstein JL, Ponzoni M, Batchelor TT. Insights into the biology of primary central nervous system lymphoma. Curr Oncol Rep. 2009; 11: 73-80.

8.Bessell EM, Hoang-Xuan K, Ferreri AJM, Reni M. Primary central nervous system lymphoma: biological aspects and controversies in management. Eur J Cancer. 2007; 43: 1141-52.

9.Ferreri AJM, Reni M, Foppoli M, Martelli M, Pangalis GA, Frezzato M, et al. High-dose cytarabine plus high-dose methotrexate versus high-dose methotrexate alone in patients with primary CNS lymphoma: a randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2009; 374: 1512-20.

10.Ferreri AJ, Cwynarski K, Pulczynski E, Ponzoni M, Deckert M, Politi LS, et al. Chemoimmunotherapy with methotrexate, cytarabine, thiotepa, and rituximab (MATRix regimen) in patients with primary CNS lymphoma: results of the first randomisation of the International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group-32 (IELSG32) phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2016; 3: e217-27.

11.Fischer L, Jahnke K, Martus P, Weller M, Thiel E, Korfel A. The diagnostic value of cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis and protein in the detection of lymphomatous meningitis in primary central nervous system lymphomas. Haematologica. 2006; 91: 429-30.

12.Bromberg JEC, Breems DA, Kraan J, Bikker G, van der Holt B, Smitt PS, et al. CSF flow cytometry greatly improves diagnostic accuracy in CNS hematologic malignancies. Neurology. 2007; 68: 1674-9.

13.Canovi S, Campioli D. Accuracy of flow cytometry and cytomorphology for the diagnosis of meningeal involvement in lymphoid neoplasms: a systematic review. Diagn Cytopathol. 2016; 44: 841-56.

Cite this article as:Zeynalova PA, Tumyan GS, Dolgushin MB, Akhmedov MI. Work-up and management of a high-risk patient with primary central nervous system lymphoma. Cancer Biol Med. 2016; 13: 514-8. doi: 10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2016.0070

Mobil I. Akhmedov

E-mail: mobilakhmedov@gmail.com

Received August 6, 2016; accepted September 21, 2016.

Available at www.cancerbiomed.org

Copyright © 2016 by Cancer Biology & Medicine

Cancer Biology & Medicine2016年4期

Cancer Biology & Medicine2016年4期

- Cancer Biology & Medicine的其它文章

- Liver cancer: challenge and prospect

- Role of microRNAs in inflammation-associated liver cancer

- Portal vein embolization for induction of selective hepatic hypertrophy prior to major hepatectomy: rationale, techniques, outcomes and future directions

- Three-dimensional printing: review of application in medicine and hepatic surgery

- Portal vein tumor thrombus is a bottleneck in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma

- Bcl-2 expression is a poor predictor for hepatocellular carcinoma prognosis of andropause-age patients