Factors associated with significant anxiety and depressive symptoms in pregnant women with a history of complications

•Original research article•

Factors associated with significant anxiety and depressive symptoms in pregnant women with a history of complications

high-risk pregnancy; anxiety; depression

1. Introduction

Women with a history of previous complications during pregnancy may face further risks during subsequent pregnancies. Compared to women without such history, these women acquire more complications during the gestation period and have a higher mortality rate.[1]Likewise, the rates of disease and mortality of the perinatal infants are apparently higher than the rates seen in normal pregnancy. Instability of mood during pregnancy can result in anxiety and depression.Furthermore, current high-risk pregnancy or history of complications increases the risk of negative mood symptoms such as anxiety and depression.[2]Previous studies have found that individuals’ mental health condition during pregnancy greatly influences the healthly development of the fetus.[3]Despite the importance of mental health during this period there are surprisingly few studies published (both in China and abroad) examining anxiety and depression in women who are pregnant.[4]We conducted a survey on anxiety and depression symptoms of women without a history of complications at the early stage of this study. This study aims to explore anxiety and depression symptoms in ‘high-risk’ pregnant women and other life factors also correlated with mood symptoms during pregnancy, in hopes of providing obstetricians with useful information that can aid early mental health interventions during this critical period.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

Potential participants were pregnant women who registered at the International Peace Maternity and Child Health Hospital in Shanghai from March 2014 to October 2014. The inclusion criteria included the following: (a)pregnant women who are permanent residents of Shanghai; (b)receiving regular obstetric examination in our research hospital; (c) having 1 or more factors meeting our criteria for ‘high-risk’pregnancy (see criteria below); (d) giving birth at our research hospital; (e) providing informed consent to participate in this study; (f) being 16 to 20 weeks pregnant.

Participants in this study were classified as ‘high risk’ if they met any of the following criteria: (a) having a history of complications: history of stillbirth or fetal mortality, history of giving birth to a congenital abnormal fetus; (b) test tube babies, pregnancy at a later age, scarred uterus.Exclusion criteria were the following: (a) currently having a psychotic or severe mood disorder such as schizophrenia, mania, paranoid psychosis and so forth (depression and anxiety were not included); (b) having negative behavior or thoughts;(c) currently having a serious somatic illness; (d) having mental retardation; (e) declining the monthly followup visit; (f) not giving birth in our research hospital; (g)persons with physical disability.

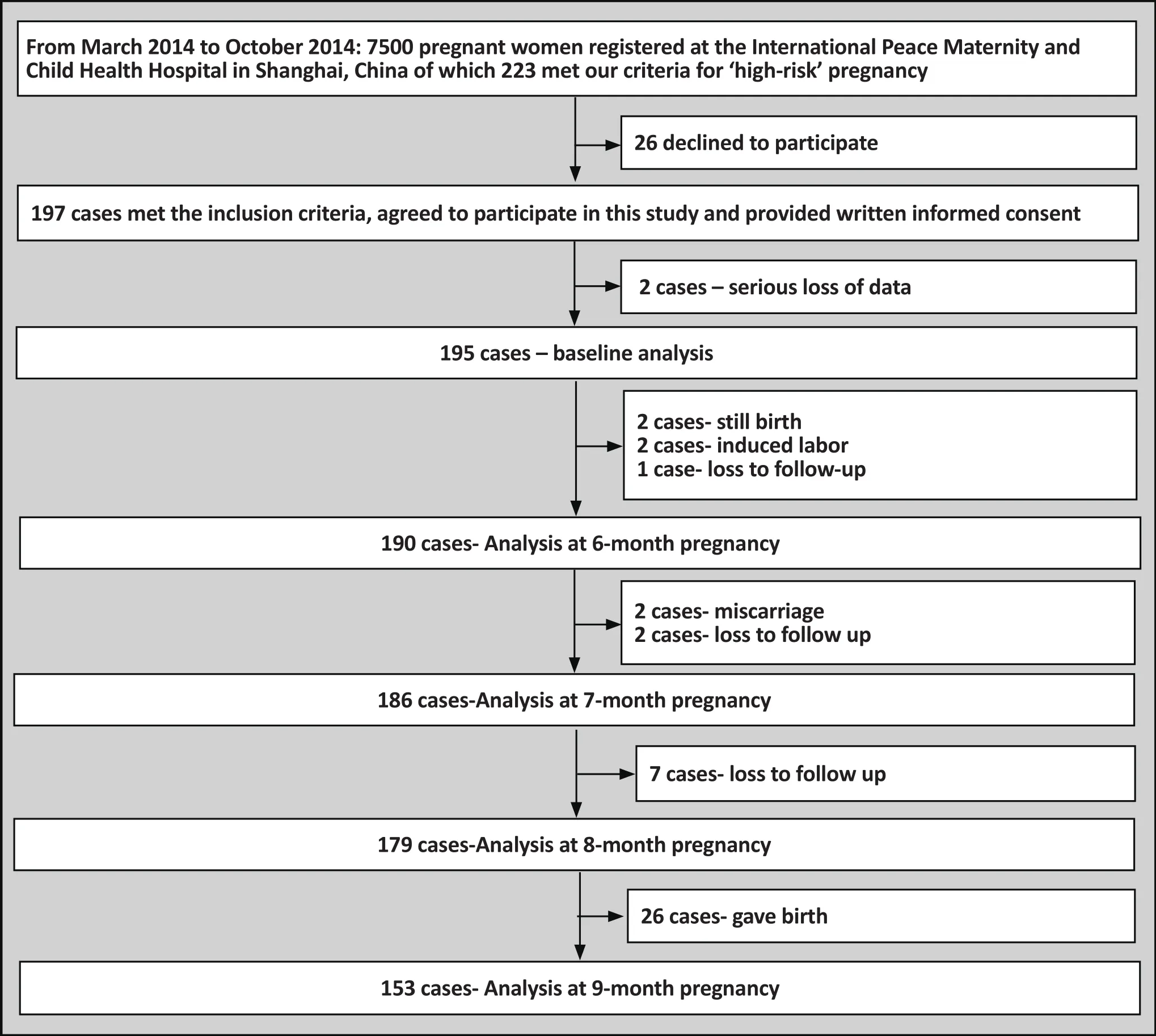

7500 pregnant women registered at the maternity outpatient clinic of the International Peace Maternity and Child Health Hospital during the study period.Screening was conducted for‘high-risk’ pregnant women at the maternity outpatient clinic every Monday; a total of 223 cases of pregnant women were screened. There were 197 pregnant women who met criteria for this‘high-risk’ qualification and provided signed informed consent. Information from 2 of the cases could not be analyzed due to a serious loss of data. In the end, there were 195 cases available for proper analysis. See fi gure 1 (flowchart) for study criteria and process.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Implementation procedures

Pregnant women who came to the International Peace Maternity and Child Health Hospital for labor registration were screened every Monday based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Participants who met the criteria and agreed to participate into the study were informed of the details of this study and provided written informed consent. All participants fi lled out the general information questionnaire (i.e. demographic data,obstetric examination data, history of complications,etc.), the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HAD)[5],the Life Event Scale (LES)[6], and the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (EPQ)[7]. All individuals in the study were assessed using the HAD and risk factor evaluation in the last 3 months of pregnancy; they were assessed using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) at 3 to 7 days, 42 days, and 3 months after labor.

HAD has been widely used in the general hospital setting to assess anxiety and depression symptoms in a variety of patients. The scale is comprised of 14 items;it is a self-rating scale with 4 grades from 0 to 3 that include anxiety and depression factors.[5]The single factor is better when the sensitivity and specificity are larger than or equal to 9. HAD has been widely used in China since the 1990s and has good reliability and validity.[8]

Cox and colleagues compiled the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in 1987.[9]It is an illnessspecific scale used for evaluating depressive mood among postpartum women. The time frame of assessment is the most recent week. The scale includes 10 items such as the sense of guilt, disordered sleep,loss of energy, loss of pleasure, and suicidal ideation.Grading is based on 1 to 4. The original author of the scale suggested 13 points be the cutoff. The scale has good reliability and validity in China and Hong Kong.[10,11]

2.2.2 Evaluation of mood symptoms

Patients with a HAD depression score of ≥9 or HAD anxiety score of ≥9 at any stage during pregnancy were considered to have significant mood symptoms. Patients with a post-labor EPDS score of ≥13 were considered to have significant depressive symptoms.

The standard scores of EPD, E, N, P, and L scales were calculated using the scoring method of the EPQ and LED scales. The statistical method of the LES scale was used to find out the corresponding life event unit(LEU) of the life event occurring during the investigation time frame from the normative scale and accumulate the units in order to obtain the total score of the LEU.

2.3 Statistical methods

Figure 1. Flowchart of the study

Double entry was used for all data using EpiData version 3.1. SPSS 22.0 was used for analysis. The statistical methods include descriptive statistics. Continuous variable analysis adopted mean (standard deviation)description whereas categorical variables adopted frequency (%) description. ANOVA was used to measure for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical variables. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare the anxiety and depression mean score of the 4 groups followed and Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to make pairwise comparison. Univariate analysis was used for the analysis of the risk factors. Selected factors that were statistically significant were used to run the binary logistic regression (forward stepwise).

3. Results

3.1 General status of participants

The mean(sd) age of the 195 participants was 31.7(3.8)years ranging from 24 to 41 years old. Educational level was the following: primary or secondary school education 22 cases (11%); college education 136 cases(70%); master’s degree or above 34 cases (17%); 3 cases(2%) were unknown. Participants had the following employment status: unemployed 22 cases (11%); blue collar workers 129 cases (66%); white collar workers 28 cases (14%); self-employed 6 cases (3%); unknown 10 cases (5%). The total value of LEU was 108.17 (95.05);EPQ E was 52.73 (8.78); EPQ N was 46.46 (5.86); EPQ P was 76.56 (11.95); EPQ L was 40.24 (8.19).

3.2 Participants depressive and anxiety symptoms

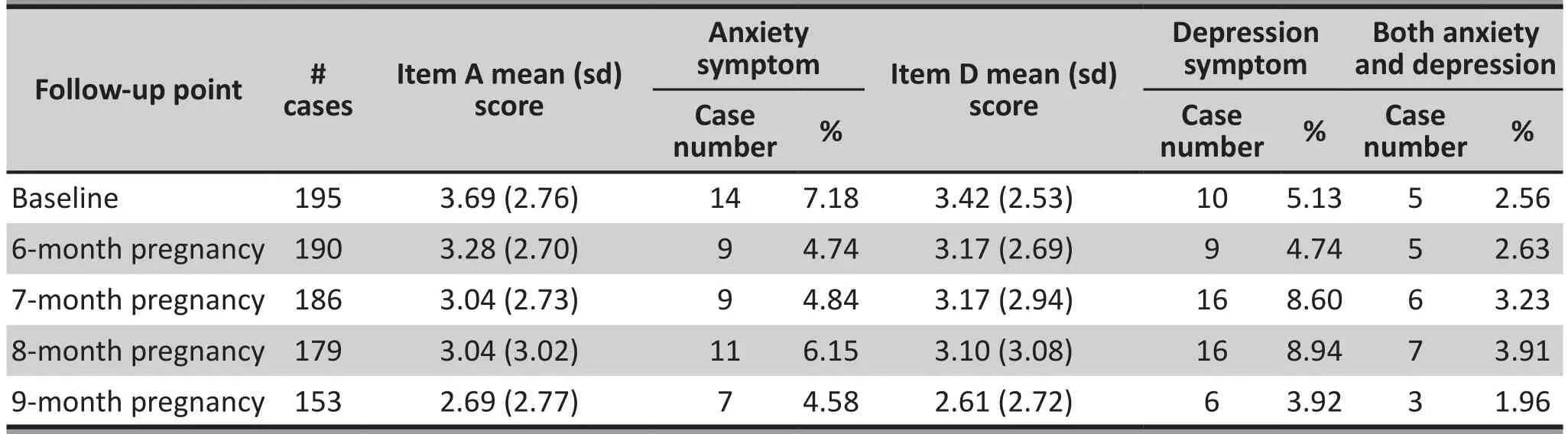

Participants at baseline with significant anxiety symptoms only had the following characteristics: n=14;educational level: high school education 2 cases, college education 9 cases, graduate level education 3 cases;mean(sd) age: 31.9 (4.5). Participants at baseline with significant depressive symptoms only had the following characteristics: n=10; educational level: high school education 1 case, college education 8 cases, graduate education 1 case; mean (sd) age 30.5 (4.6). Participants at baseline with significant anxiety and depressive symptoms had the following characteristics: n=5;educational level: high school education 1 case, college education 3 cases, graduate education 1 case; mean (sd)age 30.2 (5.3). There was no significant difference in the educational level and age of the 3 groups: (X2=0.993,p=0.991), age (F=0.534, df=2, p=0.593). See table 1.

See table 2 for HAD scores of ‘high risk’ participants at baseline. As seen in table 2, pregnant women with anxiety symptoms at baseline had a higher depression score on than the pregnant women without anxiety and depression. The anxiety score was higher in the women with both anxiety and depression symptoms than in women with anxiety symptoms only. However,there was no statistically significance difference in the depression scores of women with both anxiety and depression symptoms and women with depressive symptoms only.

Table 1. Number of cases with significant anxiety and depression symptoms and mean (sd) score on HAD at each follow-up point

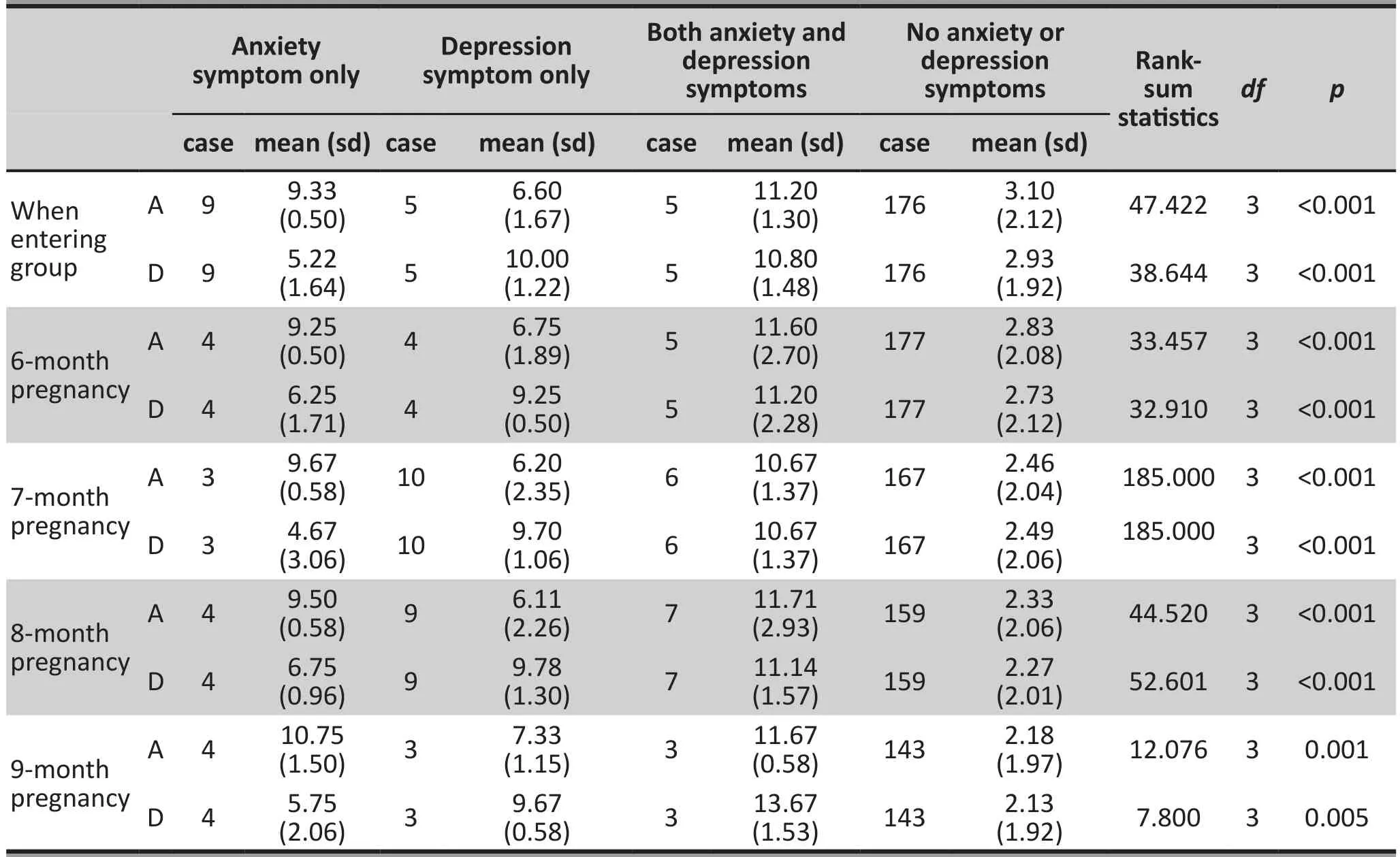

Table 2-1. HAD scores by groups with and without anxiety and depression symptoms at each follow-up point

?

3.3 Using logistic regression to analyze the risk factors of the pregnant women with anxiety symptoms only, depressive symptoms only, and both anxiety and depression symptoms when entering groups

The following independent variables were used: history of depressive episode, family history of depression,history of premenstrual tension, anxiety after pregnancy,current pregnancy was unplanned, health status during pregnancy, attitude towards current pregnancy, current concern about the fetal health, child’s gender,husband’s role in the home post pregnancy, relationship with inlaws during the recent 3 months, relationship with parents during recent 3 months, quality of marital relationship in recent 3 months, quality of other interpersonal relationships in recent 3 months, work/study pressure in recent 3 months, other life events in recent 3 months, illness in recent 3 months, current housing condition, current financial status, whether or not preventative measures for miscarriage were carried out, Life Event Scale score, Eysenck Personality Questionnaire score, age when married, age at first menstrual period, exposure to radiation 3 months before pregnancy, history of chemical exposure, occurrence of fever during pregnancy, history of term birth, previous preterm birth/abortion, past fetal/infant mortality,history of hemorrhaging, history of dystocia and surgery,other past complications (precipitate labor, prolonged labor, fetal abnormality), history of drug allergy, history of somatic diseases, history of sexually transmitted diseases, health status of husband, family history of genetic diseases, nutrition, weight, height, current systolic blood pressure, current diastolic blood pressure,heart rate, edema, thyroid, hemoglobin, urine protein,urine glucose, leucorrhea, alanine aminotransferase,blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, blood uric acid,blood glucose, OGTT test, hepatitis B virus surface antigen, and hepatitis C antibody.

Results from the univariate analysis showed that anxiety symptoms were significantly correlated with the following variables:(a) attitude towards current pregnancy, (b) quality of interpersonal relationships in the recent 3 months, (c) current financial status, (d)whether or not prevention measures were taken for miscarriage, (e) history of hemorrhaging, (f) positive urine glucose, (g) testing positive for hepatitis B,(h) systolic blood pressure, and (i) heart rate. After logistic stepwise regression analysis, only whether or not prevention measures were taken for miscarriage(OR: 8.162, 95% CI: 1.213-54.914) and testing positive for hepatitis B(OR: 8.912, 95% CI: 1.052-75.498)were related to anxiety symptoms. Also results from univariate analysis showed that depressive symptoms were significantly correlated with the following variables:(a) history of depressive episode, (b) health status during pregnancy, (c) attitude towards current pregnancy, (d) current concerns about fetal health, (e)quality of relationship with in-laws during the past 3 months, (f) quality of parental relationship during the past 3 months, (g) quality of marital relationship during the past 3 months, (h) quality of other interpersonal relationships during the past 3 months, (i) work/study pressure during the past 3 months, (j) other life events during past 3 months, (k) current financial status, (l)whether or not there was a fever during pregnancy,(m) history of preterm birth/abortion, (n) history of fetal/infant mortality, (o) history of hemorrhaging, (p)history of dystocia and surgery, (q) history of sexually transmitted diseases, (r) positive urine glucose, (s)current systolic blood pressure, and (t) heart rate. After logistic stepwise regression analysis, only positive urine glucose (OR: 30.529, 95% CI: 1.312-710.610) and history of hemorrhaging (OR: 7.122, 95% CI: 1.015-49.984)were related to depressive symptoms.

Results from the univariate analysis showed that having both depressive and anxiety symptoms was significantly correlated with the following variables:(a) history of depressive episode, (b) attitude towards current pregnancy, (c) gender of child, (d) quality of interpersonal relationships in past 3 months, (e)work/study stress in the past 3 months, (f) current housing condition, (g) current financial status, (h) history of sexually transmitted diseases,(i) positive urine glucose,(j) current systolic blood pressure, and (k) heart rate.After performing logistic stepwise regression analysis there no variables were found to be significantly correlated with having both anxiety and depressive symptoms.

3.4 Analysis of factors related to anxiety and depressive symptoms among ‘high-risk’ women during months 6 to 9 of pregnancy

Participants with significant anxiety symptoms only had a higher score on the depression measure than women without anxiety and depressive symptoms.At each follow up, the anxiety score was higher for participants with depressive symptoms than for participants without significant anxiety and depression symptoms. At each follow up, the differences in anxiety scores for participants with both anxiety and depression symptoms and participants with anxiety symptoms only were not statistically significant.At the follow up during the 9thmonth of pregnancy ‘high-risk’ women with both significant anxiety and depression scored higher on the depression scale than those women with significant depression symptoms only. However, there was no significant difference in depression scores between the two groups at the other follow up times.

During the course of all pregnancies in this study,the incidence rates of anxiety symptoms only and depression symptoms only were 14.6% and 15.7%,respectively. The incidence rate of having both anxiety and depressive symptoms was 4.6%. See table 3 for factors associated with anxiety and depressive symptoms in the ‘high-risk’ pregnancy group.The use of stepwise logistic regression analysis did not detectvariables that were significantly related to both anxiety and depression symptoms. According to the OR value in table 3, concerns about fetal health had the greatest impact onanxiety symptoms during pregnancy. As the birth approached, the relationship between quality of interpersonal relationships and depressive symptoms became more prominent.

Table 3. Factors associated with significant anxiety and depressive symptoms in women with ‘high-risk’pregnancy during their 6th to 9th months of pregnancy

3.5 Post labor depressive symptoms

In this study no subject’s total EPD score was larger than or equal to 13 at any follow-up postlabor.Therefore, there was no apparent significant depressive symptomology for participants in this study post-labor.

4. Discussion

4.1 Main findings

For women with a history of complications during pregnancy or those who are using a relatively highrisk method of conception, there can be risks towards their health, (both body and mind), as well as concerns about the fetus, and infant (e.g. potential fordystocia which can harm the mother and child). These ‘high-risk’women may have a more complicated psychological reaction to the stresses of pregnancy than other pregnant women. As well, concerns about the baby and their own future affected participants’ emotions by adding extra psychological pressure. Studies have shown that strong emotions during pregnancy can influence the results of the pregnancy. Experiencing anxiety and depression symptoms during pregnancy can increase the likelihood of adverse pregnancy outcomes such as dystocia, preeclampsia, premature birth, and low birth weight.[12]Furthermore, there is much research showing that the mothers’ emotional status during pregnancy was an important factor that influenced the mental health status of the child afterwards.[3]For example,the risk of a child getting attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is doubled when signifcant anxiety symptoms appear during pregnancy.[13,14]Therefore,the psychological health status of pregnant women(especially those with ‘high-risk’ pregnancies) should be emphasized. Previous literature reports that approximately 5 to 13% of pregnant women have significant anxiety symptoms and 4 to 15% experience significant depressive symptoms during pregnancy.[15]In our previous report we detected anxiety and depression symptoms rates of 5-6% and 5-7.6%, respectively,in women who would not be considered as having‘high-risk’ pregnancy according to the criteria used in this current study.[16]The rates of significant anxiety and depressive symptoms in women with ‘highrisk’ pregnancy in this study were 14.6% and 15.7%,respectively, which are higher than the rates seen in women without a history of complications in pregnancy.In a study from Singapore, the rate of moderate anxiety symptoms (GAD-7 ≥ 10) in hospitalized highrisk pregnant women (n=62) was 13%; the rate of postpartum depressive symptoms (EPDS ≥ 10) was 27%.This rate of anxiety is similar to our findings, however the rate of depression they found was higher than our findings. The difference in rate of depressive symptoms could possibly be due to the usage of different measurement tools. Also, these subjects were all highrisk pregnant women who had been hospitalized and had a greater number of complications.[17]Currently,high quality research studies in China that focus on anxiety and depression in high-risk pregnant women are lacking. The research of Tan Xiaoyan and colleagues reported that the rates of anxiety and depressive symptoms in high-risk women were 31.9% and 33.2%before caesarean section, which were higher than the rates in this study.[18]That research was conducted in the form of questionnaires. The tools that were used were the Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS ≥ 50) and the Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS ≥ 50). There were 458 pregnant women that completed the questionnaires before the caesarean section. The relatively high incidence rates of anxiety and depression symptoms in that study could be related to the women in that study needing to undergo the caesarean section operation and the evaluation being conducted before the surgery.Our study was a follow-up study. The caesarean section rate of this study group was 59%.

Anxiety and depression during pregnancy are related to numerous biological, psychological and social factors.[19,20]These biological factors include changes in female hormones during pregnancy, physical health, and so forth. While psychosocial factors tend to vary, the ones most reported on are life stress, lack of social support, fear before labor, concerns about the child’s health, labor complications, quality of marital relationship, quality of relationship with inlaws, and family financial status. Our study found that whether or not there were measures taken to prevent miscarriage and testing positive for hepatitis B positive were associated with significant anxiety symptoms at baseline. At follow up health status in recent 3 months,quality of marital relationship, concerns about fetal health, attitude towards pregnancy, and role of the husband at home post-birth were associated with prominent anxiety symptoms in participants.Concern about fetal health was associated with anxiety at almost every follow-up point and had the highest OR. Taking measures to prevent a miscarriage can also have a large impact on the development of the fetal health.In addition, hepatitis B can possibly be passed on to the fetus. Therefore, concern about fetal health was significantly associated with anxiety symptoms. ‘Highrisk’ pregnant women also had more medical risk factors such as high blood sugar, high blood pressure,abnormal thyroid function, when compared to pregnant women not considered ‘high-risk’. Our study found that health status in recent 3 months was related to anxiety symptoms at the 6-month and 9-month points in the pregnancy. Urine glucose,history of hemorrhaging,health status, quality of marital relationship, attitude towards pregnancy, quality of relationship with motherin-law and concern about fetal health were significantly associated with depressive symptoms in ‘high-risk’pregnant women. In our study quality of marital relationship and quality of relationship with mother-inlaw were shown to have a significant association with depressive symptoms. This further emphasizes the importance of social support and relationships during the pregnancy period and how strain in that area of life is often associated with depressive symptoms. For women in this study the mean score on depression measures increased the further along into the pregnancy they were. Studies outside of China have also reported that poor quality of partner relationship was a risk factor for depressive symptoms during pregnancy.[21]The factors associated with anxiety and depression that were found in this study provide help in assessing and providing early intervention for psychological issues affecting pregnant women. In the future it is hoped that psychological assessment will be a regular part of check ups women receive while pregnant. Psychological interventions aimed at improving interpersonal relationships could be added to the interventions for pregnant women with more prominent depressive symptoms. Finally, family members of the woman,particularly her husband, should been couraged to also participate in the intervention program.

4.2 Limitations

In this study, no one reached criteria (i.e. EPDS score≥13) for depressive symptoms after post-partum. As a result, multivariate analysis was not performed for depressive symptoms after childbirth and depression associated factors after childbirth were notexplored. A larger sample size was needed to further explore this aspect. Also the number of cases of ‘high-risk’ women who had both anxiety and depression symptoms were few due to the sample size. The factors affecting the emotions of these pregnant women were not found.In addition, the development and outcome of these womens’ symptoms could not be analyzed. Further studies with larger sample sizes are needed.

4.3 Implications

The results in this study indicate that anxiety and depressive symptoms are more common among pregnant women with a history of complications or those using ‘high-risk’ conception methods. Concern about the fetal health was the factor with the highest association to anxiety symptoms amongst the women in our study. Interpersonal relationships, especially poor marital relationships and in-law relationships, are most associated with depressive symptoms.The results of this study could provide evidence for the screening of pregnant women with anxiety and depression as well as content for the design psychological interventions.

Funding

This project was funded by the Shanghai Municipal Commission of Health and Family Planning “Effect of cognitive psychological intervention on the anxiety of the postpartum pregnant women at high risk” project.Project number: 2009107

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest related to this manuscript.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was provided by all participants in this study.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Shanghai International Peace Maternity and Child Health Care Hospital.

Authors’ contributions

Shenxun Shi: project design, supervision, article revision.Yan Chen: project design, director of implementation,case collection, evaluation. Jing Chen: case evaluation,article writing. Jianfeng Luo: project design, sample size estimation, statistical analysis of data. Yiyun Cai, Yue Liu,Jieyan Qian: case collection, evaluation. Qing Ling, Wei Zhang: case contact, project coordination.

1. Tang XJ. [Surveillance of 6640 high-risk pregnant women]. Zhongguo Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2008; 9(6):543-545. Chinese. doi: http://dx.chinadoi.cn/10.3969/j.issn.1009-6639.2008.06.028

2. Byatt N, Hicks-Courant K, Davidson A, Levesque R,Mick E, Allison J, et al. Depression and anxiety among high-risk obstetric inpatients. Gen Hosp Psychiatry.2014; 36(6): 644–649. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.07.011

3. Kingston D, Tough S, Whitfield H. Prenatal and postpartum maternal psychological distress and infant development: A systematic review. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2012; 43(5):683-714. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10578-012-0291-4

4. Tang YF, Shi SX, Lu W, Chen Y, Wang QQ, Zhu YY, et al.[Prenatal psychological prevention trial on postpartum anxiety and depression]. Zhongguo Xin Li Wei Sheng Za Zhi. 2009; 23(2): 83-89. Chinese. doi: http://dx.chinadoi.cn/10.3969/j.issn.1000-6729.2009.02.002

5. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1983; 67(6): 361–370.doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x

6. Zhang MY, Fan B, Cai GJ, Chi YF, Wu WY, Jin H. [Life Events Scale:Norm results]. Zhongguo Shen Jing Jing Shen Ji Bing Za Zhi. 1987; 13(2): 70-73. Chinese

7. Gong YX. [The Chinese revision of Eysenck’s Personality Questionnaire]. Xin Li Ke Xue. 1984; 4: 13-20. Chinese

8. Ye WF, Xu JM. [Application and evaluation of “General Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale” used in the patients of comprehensive hospital]. Zhongguo Xing Wei Yi Xue Za Zhi. 1993; 3: 17-19. Chinese

9. Cox J L, Holden J M, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987; 150(6):782-786.

10. Chou JY, Wang ZC, Luo LM, Mei LP. [Clinical application of Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale]. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2001; 13(4): 219-221. Chinese

11. Hawley C, Gale T. Detecting postnatal depression in Chinese women. Validation of the Chinese version of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1998; 172(5):271-271

12. Pesonen AK, Lahti M, Kuusinen T, Tuovinen S, Villa P,Hämäläinen E, et al. Maternal prenatal positive affect,depressive and anxiety symptoms and Birth outcomes: The PREDO study. PLoS One. 2016; 11(2): e0150058. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0150058

13. O’Connor TG, Heron J, Glover V, Alspac Study Team.Antenatal anxiety predicts child behavioral/emotional problems independently of postnatal depression. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002; 41(12): 1470. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200212000-00019

14. O’Connor TG, Heron J, Golding J, Glover V, the AL SPAC Study Team. Maternal antenatal anxiety and behavioural/emotional problems in children: A test of a programming hypothesis. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2003; 44(7): 1025.doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00187

15. Fairbrother N, Young AH, Janssen P, Antony MM, Tucker E.Depression and anxiety during the perinatal period. BMC Psychiatry. 2015; 15: 206. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12888-015-0526-6

16. Shen XX, Tang YF, Cheng LN, Su QF, Qi K, Yang YZ, et al. [An investigation of the prevalence of anxiety or depression and related risk factors in women with pregnancy and postpartum]. Lin Chuang Xin Li Wei Sheng. 2007; 21(4):254-258. Chinese. doi: http://dx.chinadoi.cn/10.3321/j.issn:1000-6729.2007.04.015

17. Thiagayson P, Krishnaswamy G, Lim ML, Sung SC, Haley CL, Fung DS, et al. Depression and anxiety in Singaporean high-risk pregnancies - prevalence and screening. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013; 35(2): 112–116. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.11.006

18. Tan XY, Guo WH, Wang AM. [Analysis of psychological state and influencing factors of high risk pregnancies before cesarean section]. Hu Li Xue Bao. 2011; 18(8):74-76. Chinese. doi: http://dx.chinadoi.cn/10.3969/j.issn.1008-9969.2011.08.028

19. Yang T, He H, Mao CY, Ji CL, Zeng SE, Hou YT, et al. [Risk factors of prenatal depression and anxiety in pregnant women]. Zhongguo Xin Li Wei Sheng Za Zhi. 2015; 4(4):246-250. Chinese. doi: http://dx.chinadoi.cn/10.3969/j.issn.1000-6729.2015.04.002

20. Chen Y, Tang YF, Qi K, Cheng LN, Shi SX. [Follow-up study of anxiety and depression with analysis of socio-psychological factors in pregnant and postpartum periods]. Shanghai Yi Xue. 2006; 29(2): 85-88. Chinese. doi: http://dx.chinadoi.cn/10.3969/j.issn.0253-9934.2006.02.005

21. Bayrampour H, Mcdonald S, Tough S. Risk factors of transient and persistent anxiety during pregnancy. Midwifery.2015; 31(6): 582-589. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2015.02.009

Dr. Jing Chen graduated with a major in clinical medicine from the Tongji University School of Medicine in 2002. She completed her master’s degree in mental diseases and mental health at the Tongji University School of Medicine; and graduated with a doctoral degree in mental diseases and mental health from the Fudan University School of Medicine. Since 2005, she has worked in the Shanghai municipal mental health center as the chief of Adolescent and Child Psychiatry.Her research interests include autism, and maternal psychological assessment and intervention.

高危孕妇焦虑抑郁症状发生率及相关危险因素

陈静,蔡亦蕴,刘乐,钱洁艳,凌青,张玮,罗剑锋,陈焱,施慎逊

高危孕妇,焦虑,抑郁

Jing CHEN1, Yiyun CAI4,1, Yue LIU1, Jieyan QIAN2, Qing LING2, Wei ZHANG2, Jianfeng LUO3, Yan CHEN2*,Shenxun SHI4,1*

Background:The occurrence of complications during the gestation period is higher among pregnant women with a history of complications than among pregnant women without previous complications. High-risk pregnancy can cause negative emotional symptoms such as anxiety and depression in pregnant women.Current research on anxiety and depression symptoms in pregnant women is sparse.Aims:To examine the incidence of anxiety and depression symptoms in pregnant women with a history of previous complications or high risk pregnancy and related risk factors.Methods:Women with a history of previous complications in pregnancy or current ‘high risk’ pregnancy(e.g. test tube fertilization, etc.) were classif i ed as ‘high risk’. 197 of these ‘high risk’ women who were in their second trimester (16 to 20 weeks) underwent a monthly comprehensive assessment using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HAD) in the last 4 months of the gestation period. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) was used for assessment and risk factor investigation 3 to 7 days, 42 days, and 3 months after childbirth.Results:The mean (sd) HAD anxiety score among ‘high-risk’women at the time of enrollment was 3.69 (2.76)and depression score was 3.42 (2.53). Significant anxiety symptoms and depression symptoms were found in 14 cases (7.18 %) and 10 cases (5.13%), respectively. Multivariate analysis showed a correlation between anxiety symptoms and history of miscarriage (OR: 8.162, 95%CI: 1.213 to 54.914)and testing positive for hepatitis (OR: 8.912, 95%CI: 1.052 to 75.498). Depressive symptoms were correlated with glucose positive urine (OR: 30.529, 95%CI: 1.312 to 710.610) and history of hemorrhaging (OR: 7.122, 95%CI: 1.015 to 49.984). General factors associated with anxiety and depression symptoms include patients’ health status in the recent 3 months, concerns about fetal health, quality of marital relationship, and relationship with inlaws.Conclusions:Anxiety and depression symptoms are commonly seen in pregnant women with a history of previous complications or current ‘high risk’ pregnancy. Patients’ recent health status, relationship with inlaws, marital quality and concerns about fetal health are associated with anxiety and depression symptoms during pregnancy.

[Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2016; 28(5): 253-262.

http://dx.doi.org/10.11919/j.issn.1002-0829.216035]

1Shanghai Mental Health Center, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China

2The International Peace Maternity & Child Health Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China

3Department of Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Fudan University, Shanghai, China

4Department of Psychiatry, Huashan Hospital of Fudan University

*correspondence: Professor Shenxun Shi. Mailing address: 600 South Wanping RD, Shanghai, China. Postcode: 200030. E-Mail: shishenxun@163.com;Professor Yan Chen. Mailing address: 910 Hengshan RD, Shanghai, China. Postcode: 200030. E-Mail: 18017316012@163.com

背景:高危孕妇与普通孕妇相比在妊娠期会出现更多的并发症,高危因素作为一种应激因素更易诱发孕妇产生焦虑、抑郁等负面情绪症状。目前国内外对高危孕妇焦虑、抑郁症状的研究相对较少。目标:调查产科高危妊娠孕妇焦虑、抑郁症状发生率及其相关危险因素。方法:对197例孕中期(16-20周)的高危孕妇在妊娠最后4月每月进行综合性医院焦虑/抑郁量表(HAD)评估和风险因素调查。产后3-7天、42天及3月进行爱丁堡产后抑郁量表(EPDS)评估和风险因素调查。结果:入组时高危孕妇HAD焦虑均分:3.69(2.76),抑郁均分:3.42 (2.53)。焦虑症状14例(7.18%),抑郁症状10例(5.13%)。多因素分析显示,怀孕有无保胎(OR:8.162, 95%CI:1.213-54.914)和乙肝阳性(OR:8.912,95%CI:1.052-75.498)与焦虑症状相关。尿糖阳性(OR:30.529, 95%CI:1.312-710.610)和既往出血史(OR:7.122,95%CI:1.015-49.984)与抑郁症状相关。孕期影响高危孕妇焦虑、抑郁症状的因素有:近3月孕妇健康状况、担心胎儿健康、夫妻关系、婆媳关系等。

结论:高危妊娠孕妇焦虑、抑郁症状较常见。近3月孕妇健康状况、婆媳关系、夫妻关系、担心胎儿健康是高危孕妇孕期焦虑、抑郁症状的风险因素。

- 上海精神医学的其它文章

- Efficacy of atypical antipsychotics in the management of acute agitation and aggression in hospitalized patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder: results from a systematic review

- Brain gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) concentration of the prefrontal lobe in unmedicated patients with Obsessivecompulsive disorder: a research of magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- A pilot longitudinal study on cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) tau protein in Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia

- Characteristics of aggressive behavior among male inpatients with schizophrenia

- The history, diagnosis and treatment of disruptive mood dysregulation disorder

- Modern methods for longitudinal data analysis, capabilities,caveats and cautions