In vitro biofilm formation in ESBL producing Escherichia coli isolates from cage birds

Ebru Sebnem Yılmaz, Nur Ceyhan Güvensen

1Mustafa Kemal University, Faculty of Art and Sciences, Biology Department, Antakya-Hatay 31040, Turkey

2Muğla Sıtkı Koçman University, Faculty of Sciences, Biology Department, Muğla 48170, Turkey

In vitro biofilm formation in ESBL producing Escherichia coli isolates from cage birds

Ebru Sebnem Yılmaz1✉, Nur Ceyhan Güvensen2

1Mustafa Kemal University, Faculty of Art and Sciences, Biology Department, Antakya-Hatay 31040, Turkey

2Muğla Sıtkı Koçman University, Faculty of Sciences, Biology Department, Muğla 48170, Turkey

ARTICLE INFO

Article history:

Accepted 14 October 2016

Available online 20 November 2016

Escherichia coli

Extended spectrum beta lactamases

Biofilm formation

Hydrophobicity

Cage birds

Objective: To determine biofilm and hydrophobicity formation ratios in extended spectrum beta lactamases (ESBL) synthesizing Escherichia coli isolates which were isolated from feces samples of 150 cage bird species randomly taken from pet shops in Hatay province, Turkey. Methods: In vitro biofilm production of 4 ESBL positive isolates were performed by Congo Red Agar (CRA), Standard Tube (ST) and Microtitre Plate (MP) methods while their hydrophobicity were examined by bacterial adhesion to hydrocarbon (BATH) test. Results: In the examined isolates, while biofilm production was found to be negative by CRA method, highest biofilm producing strain, among 4 bacteria was determined to be A42 by ST and MP methods. The Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) also displayed these confirmed findings. The hydrophobicity values of strains were determined to be between 22.45% and 26.42%. Conclusions: As a result, biofilm formation in cage bird feces originated ESBL positive Escherichia coli isolates was performed for the first time in Turkey. In order to present the relation between pathogenicity and biofilm production in animal originated ESBL positive isolates, further studies are required.

1. Introduction

The extended-spectrum beta lactamases (ESBLs)-producing Enterobacteriaceae [e.g. Escherichia coli (E. coli) and Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae)] assists remarkably in therapy deficiency and interfered illness control in human and veterinary medicine[1]. E. coli with varied ESBL genotypes have been found in wild animals, livestock, poultry and in the environment[2]. Most of microorganisms are formed biofilm, and hence increase endurance to multiple antimicrobials and produce of some cell surface constituents that conduce them alive in different communities[3,4]. Biofilm development is a complicated procedure[5]. In general, at first cells are attached to a surface and microcolonies occur. Severalsurface determinants enable binding and colony generation by E. coli[6]. Diversifying colonies synthesize a matrix and surrounds the biofilm, largerly consists of polysaccharides[7]. Consequently, planktonic cells are extricated so that they are able to accomplish the progress of the circ and colonize different surfaces[8]. Hydrophobic interactions are also important determinants that play roles in adherence and biofilm formation[9].

ESBL-producing avian E. coli could be conducted to human or mediate as sources of other genes (antimicrobial resistance and virulence) for human pathogens[10]. Therefore, living inside the matrix may increase avian E. coli's ability to achieve extrachromosomal elements, making it possible to better induce disease and thus resist improvement to the harm of animal and public health. There is very limited data on the cell surface hidrophobicity and biofilm formation of ESBL producing E. coli in pet birds. The objective of this study was to assess the cell surface hidrophobicity and biofilm formation of ESBL-producing E. coli from cage birds in Turkey.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Isolation and identification of E. coli

Freshly dropped fecal swabs (n=150) were taken from 15 different pet shops in Hatay, Turkey, from April 2013 to July 2013. Fecal swabs were streaked onto Eosine Methylen Blue Agar (EMB) supplemented with 2 μg/mL cefotaxime and incubated at 37 ℃overnight to preselect and isolate E.coli. One typical colony showing E. coli morphology per plate was selected and identified by conventional methods.

2.2. Screening and characterization of ESBL-producing E. coli

The cefotaxime, ceftazidime and ceftizoxime resistance of the isolates was investigated by agar dilution method. Any bacterial isolates which demonstrated resistance to any cephalosporin antibiotics was examined for ESBL production[11]. The isolates were also verified as ESBL producer by double disk synergy[12] and disk combination assay according to guidelines of CLSI[13]. K. pneumoniae ATCC 700603 and E. coli ATCC 25922 were used as control species. Isolates were also tested in terms of antimicrobial susceptibility against 18 antibiotics[14]. All isolates has also been previously screened for the most common beta-lactam genes (blaCTX-M, blaSHV, blaTEMand blaOXA) and phylogenetic group by PCR assays[14] (data not shown).

2.3. Hydrophobicity assay

Microbial cell surface hydrophobicity (CSH) was measured with xylene (Merck)[15]. Each of three tubes containing phosphate buffer solution-washed bacterial biomass were used in this test. And one tube was seperated as the control (Ac). One mL of hydrocarbon was put in the test tubes (Ab), then they were vortexed gently and kept in 37 ℃ for ½ h. After incubation, organic and aqueous layer were suspended from test tubes carefully and seperated to a clean tubes. The optical density (OD) at 600 nm was then measured using a UVVIS spectrophotometer. Degree of the surface hydrophobicity was calculated as (%)= (Ac- Ab)/ Ac× 100[16]. ESBL-producing E. coli strainswere categorized as:highly hydrophobic, for values > 50% ; moderately hydrophobic, for values ranging from 20% to 50% and hydrophilic, for values < 20%[17].

2.4. Qualitative biofilm formation

2.4.1. Congo red agar (CRA)

Freeman et al. have defined a qualitative method to detect biofilm generation by using CRA technique[18]. Inoculated cultures were incubated at 37 ℃ for 24 h aerobically. Black colonies with a rough, dry and crystalline consistency were regarded as positive producers, while red or smooth colonies were classified as negative strain[19].

2.4.2. Standard tube (ST)

An another method for biofilm modification was done according to the assay defined by Christensen et al.[20]. E. coli isolates were inoculated into five mL of Trypticase Soy Broth (TSB, Oxoid) and incubated at 37 ℃ for one day. Test tubes were poured and washed with sterile PBS. After then, empty test tubes were stained with 1% safranin dye for 7 min. Stained tubes were decanted gently and washed with sterile PBS again. The stained biofilm was dryed at room temperature and then, the degree of biofilm formation was visually defined. The positive sum was considered by the existence of biofilm on the inner surface of the tube[19]. The results were evaluated as weak, moderate, strong and no biofilm formation respectively, (+), (++), (+++) and (-).

2.5. Quantitative biofilm formation

2.5.1. Microtitre plate (MP) assay

Quantitation of biofilm formation was assessed using MP Assay, based on formerly reported procedures by O'Toole et al. and Stepanovic et al.[21,22]. For this aim, a volume of 200 μL aliquots of overnight TSB broth cultures of each strain was added to each well of 96-well MPs made of polystyrene (Nunc, USA) and kept for 24 h at 37 ℃ in an incubator. Then, the wells were attentively poured off and washed two times with 300 μL of phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) to move away unattached bacteria. MPs were cleared out, dried and later dyed with 0.1% crystal violet (CV) (200 μL) for 45 min, drained the CV by washing three times with distilled water, and allowed to dry for 2 h. At the end of this period, the MPs were cautiously treated two times with distilled water to elute the CV. A total of 200 μL ethanol/acetone (90:10) was put to every well to shed residual CV from the wells. The OD was measured at 540 nm (OD540) using a MP reader (Thermo Scientific-Multiskan FC).

As negative control, only sterile TSB was put to the wells of MPs, and every bacterium was tested in three times at 37 ℃ for 24 h. MPs including sterile TSB, nonbiofilm forming strains and accepted biofilm forming strains were evaluated as controls for cutoff, negative controls, and positive controls, respectively. All results were averaged and standard deviations were calculated. The cut off values were defined as three standard deflections afore the mean ODc[22]. In our work, each E. coli strain was identified as: weak biofilm former OD = 2 × ODc, moderate biofilm former 2 × ODc <OD = 4 × ODc, or strong biofilm former OD >4 × ODc[23].

2.5.2. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis

SEM is an unique device for defining biofilms because of its ability to ensure an incidental view on the surface topography at high resolution and magnification. Therefore, in this study, avian E. coli biofilms on the treated slides were also observed by SEM monitoring with some modifications in method of Fratesi et al.[24]. For examination under SEM, biofilms grown on glass coverslips in TSB were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde for 4 h, treated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.4). One percent osmium tetroxide in PBS (pH 7.4) was used as an second fixative for 1 h and dewatered in ascending amounts of ethanol. Following dehydration, the specimens were left open to the air and fitted on metal studs with a double-sided adhesive plaster. The samples were then sputter coated with palladium (Emitech K550X Sputter Coating Systems, England)[23]. All specimens were analyzed under a SEM (Jeol JSM-7600F, Japan) at an accelerating voltage of 15 Kv[22].

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of ESBL-producing E. coli

In total, 4 ESBL-producing E. coli were obtained from 150 fecal swabs. Isolates were isolated from Poephila guttata (n=1) and Melopsittacus undulatus (M. undulatus, n=3). Four antibiotic discs {amoxicillin-clavulanic acid [(10+20) μg], aztreonam (30 μg), ceftazidime (30 μg), cefotaxime (30 μg)} were tested by double disc synergy method (DDSM). In the test the distance between discs were adjusted to 25 mm and according to the existence of synergy, all isolates were evaluated as ESBL positive. Disk combination test was made similar to DDSM. In this test, as a difference, ceftazidime (30 μg), ceftazidime (30 μg)+clavulanic acid (10 μg), cefotaxime (30 μg), cefotaxime (30 μg)+clavulanic acid (10 μg) and cefpodoxime (30 μg), cefpodoxime (30 μg)+clavulanic acid (10 μg) discs were placed reciprocatively on Mueller Hinton Agar (MHA, Merck) and incubated at 37 ℃ for 18-24 h. ESBL result was decided in case of ≥5 mm increase of inhibition zone of cephalosporin disk in presence of clavulanic acid. All ESBL types belonged to the CTX-M and TEM- family and were classified into the B1 phylogenetic group (data not shown). The 4 isolates displayed different frequencies of antimicrobial susceptibility amongst 18 antibiotics (data not shown).

3.2. Microbial adhesion to hydrocarbons

ESBL-producing four E. coli isolates were tested in terms of their ability of hydrocarbons. About 100 % E. coli isolates have moderate capability (CSH value 22.45-26.42) to adhere to hydrocarbons (Table 1).

3.3. In vitro biofilm formation

Among four isolates, CRA method detected none of them as biofilm producers. Conversely, ST and MP assay results showed that all isolates produced biofilms at different degrees. In the study, the biofilm-formation capabilities of four ESBL-producing E. coli strain at 37 ℃ for 24 h in TSB were given in Table 1. The experiments were performed at 24 h, 48 h and 72 h. Because of the reduction in biofilm production for 48 h and 72 h, the measurements were continued for 24 h. All data were reported as mean ± SE of the mean.

The crystal violet holded status of strains cultivated on microplates through biofilms formed at the end of 24 h. The OD values of strains at 540 nm varied between 0.401 and 2.169 while ODc values varied between 1.147 and 4.215 (Table 1). According to both MP assay and ST methods the A35 isolate formed weak biofilm, A40 and A55 formed medium level biofilm and A42 formed the best biofilm producer.

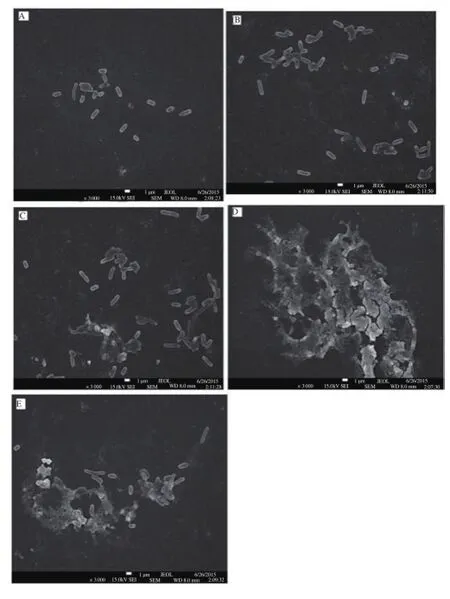

The biofilm production status of isolates was also controlled by SEM monitoring at the same time (Figure 1). When the SEM displays of isolates were examined, it was determined that their biofilm productions were similar to ST and MP assays. Such cells are planktonic in initial SEM photos (negative control) and there is no biofilm formation, (Figure 1a), densest biofilm display was obtained in A42 (Figure 1d) On the other hand, SEM displays of A35, A40 and A55 demonstrated much less dense biofilm formations (Figure 1b, 1c and 1e).

Table 1 Adhesion capability of E. coli isolates to hydrocarbon and the biofilm formation capacities.

Figure 1. Biofilm SEM images of E.coli isolates (A35, A40, A42, A55) on the microtiter plates.

4. Discussion

E. coli is one of the world's best-characterized organisms and resides in the lower intestines of a slew of animals[25]. Healthy birds harbor only minimal numbers of E. coli their intestinal track[26,27]. In this study, 4 E. coli isolated from two different bird species (2.7% of 150 cage birds sampled) displayed a certain phenotypical and genotypical conformation for ESBL production. Regarding studies on the ESBL prevalence in companion animals in the America, results with variable rates like 3%, 40% and 68% were obtained[28-30]. All of the isolates (100%) were also resistant to non-beta lactam antibiotics, and showed multi-drug resistance. Multiple antimicrobial resistance bacteria were documented to have more virulent factors with reference to sensitive isolates[31]. A similar finding was also reported by Valentin et al. who found that ESBL/pAmpC producing E. coli strains were also resistant to other class of antimicrobials agents[32]. This could partly be explained by the fact that the plasmids harboring ESBL/pAmpC genes frequently carry other resistance genes that are responsible for other class antimicrobials, such as fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides and trimethoprimsulphamethoxazole[33].

Among four major phylogenetic groups of E. coli, group A and B1 are mostly considered as non-pathogenic, while group B2 and D mainly belong to the virulent extraintestinal strains[34]. All of the ESBL positive isolates are included into B1 phylogenetic group, in this study. It is possible to think that ESBL genes are one of the most spread genes among commensal E. coli isolates in birds.

CSH performs an important role on bacterial adhesion. CSH is a mixed interference among with the cell surface elements and outside the cell[11,35]. Resistance to ß-lactam antibiotics can alter the bacterial cell all and plays the bacteria more coherent[11,36]. And CSH could also be modified as a factor of the microbial physiology[37]. We detected that ESBL producing isolates had moderate CSH capability as 100%. Norouzi et al. reported that value of the hydrophobicity in ESBL and non ESBL producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates was 38.85% and 30% respectively[11]. Biofilm production is so significant virulence parameter in many nosocomial infections that biofilm occured in 65% of nosocomial infections[38]. The association between biofilm formation and virulence factors was reported as variable[4,39]. Sharma et al. reported that there was an important interaction between multiple virulence factors and ESBL production in extraintestinal E. coli[40]. In our study, that four ESBL positive E. coli isolates were positive biofilm formation was not found by using CRA method. The majority of ESBL producing E. coli showed weak biofilm formation and belonged to a commensal phylogenetic group[4]. Today, commonly used methods for biofilm researches are qualitative ST and quantitative MP techniques[10,41]. In our work, it was determined that one isolate was weak (A35), two isolates were moderate (A40 and A55) and one isolate was strong (A42) biofilm producers by two methods. A42 was detected to be the best biofilm producer among four strains. It is likely to be the result of more biofilm production capability of A42 and its wider antibiotic resistance pattern than the other strains. Because, all four E. coli strains enter the same phylogenetic group, A42 phenotypically shows a wider beta-lactam antibiotic resistance properties compared to other strains.

Resistance phenotype of A42 comprises ampicillin, amoxicillin/ clavulanic acid, nalidixic acid, ciprofloxacin, cephalothin, aztreonam, tetracycline, cefepime, streptomycin, sulphamethoxazole/ trimethoprim, chloromphenicol, canamycin[14]. In a similar another study, of the 100 isolates with 60.2% uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC), 72 isolates pointed out a biofilm positive phenotype in the ST method and the isolates were defined as highly positive (17, 23.6%), moderate positive (19, 24.3%) and weakly positive (36, 50.0%). Similarly on Congo Red agar medium, biofilm positive phenotype strains were identified as highly positive (6, 6%), moderate positive(80, 80%) and weakly positive (14, 14%). A before mentioned work also pick outs the prevalence and antimicrobial drug susceptibility profile of biofilm and non-biofilm forming UPEC isolates[42]. Rendiwala et al. performed on 100 biofilm former strains isolated from various clinical implants[43]. In total, 69 of 100 medical strains tested, were obtained to be biofilm producers by MP assay. Their results showed antibiotic resistance pattern of microbial strains proposing plurality as multiple antibiotic resistant. Phenotypic assessment pointing out phrase of different antimicrobial-resistance mechanisms comprises ESBL (23%), carbapenemase (34%) and AmpC production (7%), carbapenem impermeability (41%), and modification of PBP (13%) liable for resistance among beta lactam antibiotics tested[43].

In our study, all of the studied E.coli strains were also examined to check biofilm formation using a SEM. The SEM makes it possible for the investigation of bacteria/surface interaction and may be used as a semi-quantitative method[17]. The images obtained from SEM approved the biofilm formation trends of these strains. Moreover, it revealed that ST, MP and SEM analysis could be used without doubt on biofilm researches of this group of members because of giving consistent results with each other.

In conclusion, this is the first research, to our knowledge, of ESBL-producing E. coli on CSH and biofilm formation in cage birds in Turkey. Despite the fact that the+se birds often live in close contact with owners and other bird species and other people in pet shops, the transmission among them occur. Further works should be realized in the future for the purpose of figuring out the association between the ESBL-producing E.coli and biofilm related genes compared to other animal isolates.

Conflict of interest statement

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Guenther S, Grobbel M, Beutlich J, Bethe A, Friedrich ND, Goedecke A, et al. CTX-M-15-type extended-spectrum beta-lactamases-producing Escherichia coli from wild birds in Germany. Environ Microbiol Rep 2010; 2(5): 641-645.

[2] Hasan B, Islam K, Ahsan M, Hossain Z, Rashid M, Talukder B, et al. Fecal carriage of multi-drug resistant and extended spectrum β -lactamasesproducing E. coli in household pigeons, Bangladesh. Vet Microbiol 2014; 168(1): 221-224.

[3] Kragh KN, Hutchison JB, Melaugh G, Rodesney C, Roberts AEL, Irie Y, et al. Role of multicellular aggregates in biofilm formation. mBio 2016; 7(2): 1-11.

[4] Cornejova T, Venglovsky J. Gregova G, Kmetova M, Kmet V. Extended spectrum beta-lactamases in Escherichia coli from municipal waste water. Ann Agric Environ Med 2015; 22(3): 447–450.

[5] Penesyan A, Gillings M, Paulsen IT. Antibiotic discovery: combatting bacterial resistance in cells and in biofilm communities. Molecules 2015; 20(4): 5286-5298.

[6] Valentini M, Filloux A. Biofilms and cyclic di-GMP (c-di-GMP) signaling: lessons from Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other bacteria. J Biol Chem 2016; 291(24): 12547-12555.

[7] Hobley L, Harkins C, MacPhee CE, Stanley-Wall NR. Giving structure to the biofilm matrix: an overview of individual strategies and emerging common themes. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2015; 39(5): 649-669.

[8] Wang X, Preston JF, Romeo T. The pgaABCD locus of Escherichia coli promotes the synthesis of a polysaccharide adhesin required for biofilm formation. J Bacteriol 2004; 186(9): 2724–2734.

[9] Krasowska A, Sigler K. How microorganisms use hydrophobicity and what does this mean for human needs? Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2014; 4(112): 1-7.

[10] Skyberg JA, Siek KE, Doetkott C, Nolan LK. Biofilm formation by avian Escherichia coli in relation to media, source and phylogeny. J Appl Microbiol 2007; 102(2): 548–554.

[11] Norouzi F, Mansouri S, Moradi M, Razavi M. Comparison of cell surface hydrophobicity and biofilm formation among ESBL-and non–ESBL-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates. African J Microbiol Research 2010; 4(11): 1143-1147.

[12] Jarlier V, Nicolas MH, Fournier G, Philippon A. Extended broadspectrum β-lactamases conferring transferable resistance to newer β-Lactam agents in Enterobacteriaceae: hospital prevalence and susceptibility patterns. Clin Infect Dis 1988; 10(4): 867-878.

[13] CLSI. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: 17th informational supplement. Wayne: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2012.

[14] Dolar A. Investigation of the presence of Extended Spectrum Betalactamase producing Escherichia coli in cage birds [Msc Thesis]. Turkey: Mustafa Kemal University, Institute of Natural &Applied Sciences; 2015.

[15] Sweet SP, Macfarlane TW, Samarayanake LP. Determination of the cell hydrophobicity of oral bacteria using a modified hydrocarbon adherence method. FEMS Microbiol Lett 1987; 48(1-2): 130–134.

[16] Li J, McLandsborough LA. The effects of the surface charge and hydrophobicity of Escherichia coli on its adhesion to beef muscle. Int J Food Microbiol 1999; 53(2-3): 185-193.

[17] Di Ciccio P, Vergara A, Festino AR, Paludi D, Zanardi E, Ghidini S, et al. Biofilmformation by Staphylococcus aureus on food contact surfaces: relationship with temperature and cell surface hydrophobicity. Food Cont 2015; 50: 930-936.

[18] Freeman DJ, Falkiner FR, Keane CT. New method for detecting slime production by coagulase negative staphylococci. J Clin Pathol 1989;42(8): 872–874.

[19] Tel OY, Aslantas Ö, Keskin O, Yılmaz ES, Demir C. Investigation of the antibiotic resistance and biofilm formation of Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from gangrenous mastitis of ewes. ActaVet Hung 2012; 60(2): 189–197.

[20] Christensen GD, Simpson WA, Younger JJ, Baddour LM, Barrett FF, Melton DM, et al. Adherence of coagulase-negative staphylococci to plastic tissue culture plates: a quantitative model for the adherence of staphylococci to medical devices. J Clin Microbiol 1985; 22(6): 996–1006.

[21] O'Toole GA, Pratt LA, Watnick PI, Newman DK, Weaver VB, Kolter R. Genetic approaches to study of biofilms. Methods Enzymol 1999; 310: 91–109.

[22] Stepanovic S, Cirkovic I, Ranin L, Svabic-Vlahovic M. Biofilm formation by Salmonella spp. and Listeria monocytogenes on plastic surface. Lett Appl Microbiol 2004; 38(5): 428–432.

[23] Rao RS, Karthika RU, Singh SP, Shashikala P, Kanungo R, Jayachandran S, et al. Correlation between biofilm production and multiple drug resistance in imipenem resistant clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii. Indian J Med Microbiol 2008; 26(4): 333–337.

[24] Fratesi SE, Lynch FL, Kirkland BL, Brown LR. Effects of SEM preparation techniques on the appearance of bacteria and biofilms in the Carter Sandstone. J Sediment Res 2004; 74(6): 858-867.

[25] Hufnagel DA, Depas WH, Chapman MR. The biology of the Escherichia coli extracellular matrix. Microbiol Spectr 2015; 3(3). doi: 10.1128/ microbiolspec.MB-0014-2014.

[26] Samour J. Escherichia coli infections. In: Samour J, editor. Avian Medicine. London: Mosby; 2007. p. 352-353.

[27] Giacopello C, Foti M, Fisichella V, Lo Piccolo F. Antibiotic resistance patterns of gram negative bacterial isolates from breeder canaries (Serinus canaria domestica) with clinical disease. J Exot Pet Med 2015; 24(1): 84-91.

[28] Ma J, Zeng Z, Chen Z, Xu X, Wang X, Deng Y, et al. High prevalence of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance determinant sqnr, aac(6')-Ibcr, and qepA among ceftiofur-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolates from companion and food-producing animals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009; 53(2): 519–524.

[29] O'Keefe A, Hutton TA, Schifferli DM, Rankin SC. First detection of CTX-M and SHV extended-spectrum-lactamases in Escherichia coli urinary tract isolates from dogs and cats in the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2010; 54(8): 3489–492.

[30] Shaheen BW, Nayak R, Foley SL, Kweon O, Deck J, Park M, et al. Molecular characterization of resistance to extended-spectrum cephalosporins in clinical Escherichia coli isolates from companion animals in the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011; 55(12): 5666-5675.

[31] Baquero F, Negri MC, Morosini MI, Bla'zquez J. Antibiotic-selective environments. Clin Infect Dis 1998; 27(1): 5-11.

[32] Valentin L, Sharp H, Hille K, Seibt U, Fischer J, Pfeifer Y, et al. Subgrouping of ESBL-producing Escherichia coli from animal and human sources: an approach to quantify the distribution of ESBL types between different reservoirs. Int J Med Microbiol 2014; 304(7): 805-816.

[33] Li L, Wang B, Feng S, Li J, Wu C, Wang Y, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of extended-spectrum ß-lactamase and plasmid-mediated fluoroquinolone resistance genes in Escherichia coli isolated from chickens in Anhui Province, China. PLoS One 2014; 9(8): e104356.

[34] Clermont O, Bonacorsi S, Bingen E. Rapid and simple determination of the Escherichia coli phylogenetic group. Appl Environ Microbiol 2000; 66(10): 4555-4558.

[35] Courtney HS, Ofek I. Relationship between expression of the family of M Proteins and lipoteichoic acid to hydrophobicity and biofilm formation in Streptococcus pyogenes. PLoS ONE 2009; 4(1): e4166.

[36] Lazar VM. Study of antibiotic resistance, production of ESBL and other virulence factors in enterobacterial strains isolated from nosocomial infections in cardiovascular devices inserted patients. 14th Eur Cong Clin Microbial Infect Dis 2004. p. 902.

[37] Rodriquez-Bano J, Pascual A. Clinical significance of extended spectrum-lactamases. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2008; 6(5): 671-683.

[38] Potera C. Microbiology: forging a link between biofilms and disease. Science 1999; 283(5409): 1837-1839.

[39] Naves P, del Prado G, Huelves L, Gracia M, Ruiz V, Blanco J, et al. Correlation between virulence factors and in vitro biofilm formation by Escherichia coli strains. Microb Pathog 2008; 45(2): 86–91.

[40] Sharma S, Bhat GK, Shenoy S. Virulence factors and drug resistance in Escherichia coli isolated from extraintestinal infections. Indian J Med Microbiol 2007; 25(4): 369-373.

[41] Oosterik LH, Tuntufye HN, Butaye P, Goddeeris BM. Effect of serogroup, surface material and disinfectant on biofilm formation by avian pathogenic Escherichia coli. Vet J 2014; 202(3): 561–565.

[42] Ponnusamy P, Natarajan V, Sevanan M. In vitro biofilm formation by uropathogenic Escherichia coli and their antimicrobial susceptibility pattern. Asian Pac J Trop Med 2012; 5(3): 210-213.

[43] Revdiwala S, Rajdev BM, Mulla S. Characterization of bacterial etiologic agents of biofilm formation in medical devices in critical care setup. Crit Care Res Pract 2012; 2012: 1-6.

Document heading 10.1016/j.apjtm.2016.10.003

11 August 2016

in revised form 12 September 2016

✉First and Ebru Sebnem Yılmaz, Mustafa Kemal University, Faculty of Art and Sciences, Biology Department, Antakya-Hatay 31040, Turkey.

Tel: +90-3262455836

Fax: +90-3262455867

E-mail: ebrusebnem@gmail.com

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine2016年11期

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine2016年11期

- Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine的其它文章

- Modifiable determinants of attitude towards dengue vaccination among healthy inhabitants of Aceh, Indonesia: Findings from a communitybased survey

- Clinical significance of dynamic detection for serum levels of MCP-1, TNF-α and IL-8 in patients with acute pancreatitis

- Expression and mechanism of action of miR-196a in epithelial ovarian cancer

- Protective effect of antioxidant on renal damage caused by Doxorubicin chemotherapy in mice with hepatic cancer

- Mechanism of action of Zhuyu Annao pill in mice with cerebral intrahemorrhage based on TLR4

- Acetylcholinesterase, butyrylcholinesterase and paraoxonase 1 activities in rats treated with cannabis, tramadol or both