Anti-tubercular peptides: A quest of future therapeutic weapon to combat tuberculosis

Ameer Khusro, Chirom Aarti, Paul Agastian

Research Department of Plant Biology and Biotechnology, Loyola College, Nungambakkam, Chennai -600034, Tamil Nadu, India

Anti-tubercular peptides: A quest of future therapeutic weapon to combat tuberculosis

Ameer Khusro, Chirom Aarti, Paul Agastian✉

Research Department of Plant Biology and Biotechnology, Loyola College, Nungambakkam, Chennai -600034, Tamil Nadu, India

ARTICLE INFO

Article history:

Accepted 20 September 2016

Available online 20 November 2016

Anti-tubercular peptides

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

Therapeutic drugs

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is a symbolic menace to mankind, infecting almost one third of the world's populace and causing over a million mortalities annually. Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis) is the key pathogen of TB that invades and replicates inside the host's macrophage. With the emerging dilemma of multi-drug resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) and extensivelydrug resistant tuberculosis (XDR-TB), the exigency for developing new TB drugs is an obligation now for worldwide researchers. Among the propitious antimycobacterial agents examined in last few decades, anti-tubercular peptides have been substantiated to be persuasive with multiple advantages such as low immunogenicity, selective affinity to bacterial negatively charged cell envelopes and most importantly divergent mechanisms of action. In this review, we epitomized the current advances in the anti-tubercular peptides, focusing the sources and highlighting the mycobactericidal mechanisms of promising peptides. The review investigates the current anti-tubercular peptides exploited not only from human immune cells, human non-immune cells, bacteria and fungi but also from venoms, cyanobacteria, bacteriophages and several other unplumbed sources. The anti-tubercular peptides of those origins are also known to have unique second non-membrane targets within M. tuberculosis. The present context also describes the several cases that manifested the severe side effects of extant anti-TB drugs. The downfall, failure to reach clinical trial phases, inept to MDR- or XDR-TB and severe complications of the currently available anti-tubercular drugs accentuate the imperative necessity to develop efficacious drugs from adequate anti-tubercular peptides. Keeping in view of the emerging trends of drug resistant M. tuberculosis globally and unexampled mycobactericidal characteristics of peptides, the anti-tubercular peptides of varied origins can be used as a potential weapon to eradicate TB in future by developing new therapeutic drugs.

1. Introduction

Bacterial infections are significant threats globally, causing over a million deaths every year. Tuberculosis (TB) is one of the most serious tropical diseases, caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis(Mtb). TB is a severe airborne fatal disease which infects one third of the world's population. TB is a global pulmonary health problem and is more common among men than women. TB infects all age groups, mostly affects adults. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) survey, there were 8.6 million new active cases of TB and 1.3 million deaths during 2012 [1]. There were approximately 9.6 million cases of active TB estimated in 2014 which culminated in 1.5 million deaths.

Indeed, TB is an endemic disease in the developing countries and the majority of active TB cases were in the South-East Asia (29%), followed by African (27%) and Western Pacific (19%) regions. More than 95% of deaths occurred in developing countries and India alone accounts for 26% of total TB cases. In the mid-1990s,the WHO developed the DOTS (direct observed therapy strategy) to control TB. This strategy was adopted by most of the countries and confirms a short-course of chemotherapy treatment by administering crucial first-line drugs (isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol and pyrazinamide), followed by treatment with isoniazid and rifampicin for a period of four months. The emergence of multidrug resistant (MDR) Mtb and disease recrudesces were one of the consequences of this strategy. Surprisingly, among the newly infected cases of TB, approximately 13% were co-infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) due to the impairment of the immune system of the patient, leading to the delayed diagnosis and treatment of TB [2]. This is because HIV infected persons are compromised with their immune systems.

Mtb is a weak Gram-positive bacterium that affects human macrophages, leading to TB. Mtb is aerobic and rod-shaped non-motile bacillus. The bacterium divides with extremely slow rate with a generation time of 16-20 h. The high lipid content on the outer membrane of this bacterium provides its unique characteristics and stained with Ziehl–Neelsen stain (acid-fast stain) during its microscopic observation. TB causing mycobacteria viz. Mycobacterium bovis (M. bovis), Mycobacterium africanum (M. africanum), Mycobacterium canetti (M. canetti) and Mycobacterium microti (M. microti) belong to M. tuberculosis complex (MTBC). Among them, M. bovis and M. africanum are not widespread at present. On the other hand M. canetti and M. microti are rare, limited to Africa only.

In spite of the discovery of streptomycin and first-line anti-TB drugs, TB continued to ravage the under-developed and developing countries. The rate of TB development rose once again with the onset of HIV infections, leading to the utilization of several drugs towards its cure and addressed the dominant cause of the emergence of MDR mycobacterium strains. In the current scenario, there is an emergence of multidrug resistant MDR strains, threatening global TB control. MDR-TB is a form of TB that is resistant to first-line anti-TB drugs, at least to isoniazid (INH) and rifampicin (RIF). The rise of MDRTB led to the use of second-line drugs (para-aminosalicylic acid, cycloserine, terizidone, ethionamide, prothionamide, thioacetazone, linezolid, levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, ofloxacin, gatifloxacin and capreomycin) that are very expensive, toxic and require long term treatment, causing the poor patient compliance. In 2014, 480 thousand cases were reported globally developing MDR-TB, with mortality counts of 123 thousand.

XDR-TB is a subset of MDR-TB which is resistant to the secondline anti-TB drugs, fluoroquinolones, and one of the three injectable anti-TB agents (e.g. amikacin, kanamycin and capreomycin). Currently, the cases of MDR-TB and XDR-TB are continuously emerging and few countries reported at least one case of XDR-TB, which represented 9.6% of all MDR-TB cases.

2. Mtb pathogenicity

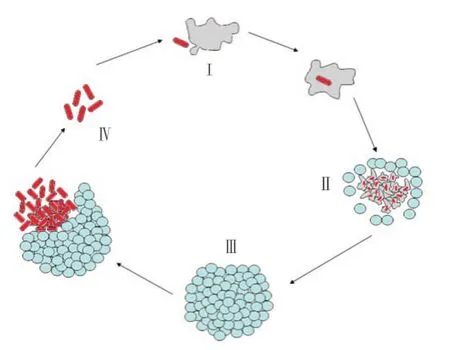

The intracellular pathogen, Mtb primarily infects human pulmonary macrophage. Macrophages are specialized cells of the immune system that engulf and remove the invading microorganisms through phagocytosis process. In general, during this process microorganisms are trapped into the phagosomes which fuse with lysosome and forms phagolysosome. Eventually, the digestive process occurring inside the phagolysosomes results into the destruction of invaded microorganisms. However, Mtb after phagocytised escapes from this defence mechanism by infecting macrophages and survive within the adverse environment. Mtb utilizes macrophages for its own replication process (Figure 1). The defence property of Mtb relies on several survival strategies. Unlike non-pathogenic mycobacterium strains, first of all the pathogenic Mtb arrests the maturation process of phagosomes and prevents the acidification of phagosomal compartments. It also inhibits the formation of the lysosomes and phagosomes complex. Further, the bacterium impairs the apoptosis of macrophage and suppresses the antimicrobial responses, thus helping the bacterium to escape from the phagosomes. The bacterium becomes undetectable to innate immune system because MHC class II antigen avoids its presentation. In this manner, Mtb is able to manipulate and survive in the adverse environment of pulmonary or any other parts of the host macrophages.

Figure 1. Pathogenicity of Mtb and utilization of macrophage, where I -Macrophage, II - Leucocytes, III - Granuloma and IV - Mtb.

Extensive reports have demonstrated that in spite of the digestive property of macrophages, Mtb has developed multiple adaptive strategies to destruct the phagosomal pathways and survive intracellularly in the host macrophages [3]. The cell envelop of Mtb constituting diverse lipid contents is a major factor towards its virulent property. The lipids such as Sulfated glycolipid (SL), Trehalose dimycolates (TDM), Dimycocerosate phthiocerol (DIM), Lipoarabinomannan (LAM), Mannose capped lipoarabinomannan (Man-LAM) and Phosphatidylinositol mannoside (PIM) present in the cell envelop contributes to the virulence of the bacterium. Lipoarabinomannan (LAM) and phosphatidylinositol mannoside (PIM) have the capability to interfere with the host phagosome pathway [4]. LAM and PIM arrest phagosome fusion and acidification [5]. On the other hand, SL and TDM prevent the fusion of lysosome [6]. However, the formation of permeability barrier by cell envelops and inhibition of acidification is carried out by DIM [7].

According to the report of Kusner and Barton [8], the virulent Mtb restricts CR-mediated Ca2+signalling during phagocytosis process and arrests the acidification and fusion mechanism. Man-LAM may incorporate with Mtb-containing phagosomes membrane and blocks the macrophage sphingosine kinase (SK) or Ca2+/calmodulin phosphatidylinositol (PI)3 kinase hVPS34 cascade and PIP3 (phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate) production, resulting the inactivation of early endosome antigen 1 (EEA1), a major component in phagosome maturation mechanism [9]. LAM may also impair the host phagosome maturation process by activating p38 mitogenactivated protein kinase (p38 MAPK), which are responsible for the down-regulation of EEA1 recruitment mechanism [5]. PIM has the capablity to avoid phagosomal acidification by stimulating the fusion of Mtb-containing phagosome with early endosome compartments. It facilitates the access to nutrients necessary for the pathogen's survival strategy. The depletion of these essential nutrients results into the inactivation of Mtb inside macrophages [7].

TACO (tryptophan aspartate coat protein) is a host protein, residing on the live and virulent Mtb containing phagosomes. Unlike the uncoated phagosomes, TACO-coated Mtb-containing phagosomes will not be presented to lysosomes for degradation process and thus inhibits the fusion of the phagosome [10]. Mtb arrests apoptosis of the infected cells at the preliminary stage and induces necrosis-like cell death to escape from the hosts [11].

Recently, a TACO binding protein called as mycobacterial Lipoamide dehydrogenase C (LpdC) has been studied to induce the virulence characteristics of Mtb. The protein supports Mtb to avoid the toxicity of host's reactive oxygen species (ROS) by forming a constituent of peroxynitrite reductase/peroxidase [4]. The pathogenicity mechanism and virulence characteristics of Mtb explained above clearly show that Mtb has developed survival strategies to evade phagocytosis process.

The current scenario of anti-tubercular therapies has drawn attention to achieve competent and durable treatment of the emerging problems of TB. In the last few years, the naturally occurring compounds and their derivatives due to vast biological properties have been taken into account for the investigation and development of new potent drug candidates. Among the naturally occurring molecules, antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) have been found to be more effective with invading potential due to their unique molecular features and multiple mode of action. These peptides are known to bind with a broad range of biological targets and show both antimycobacterial as well as immunomodulatory properties.

3. Anti-tubercular peptides as new alternative mycobactericidal agents

Although several alternate strategies have ensued in the last few decades in order to combat TB, anti-tubercular peptides remain to be the leading alternative due to their versatility nature by virtue of several mechanism and immunomodulation properties. In fact, antitubercular peptides are the antimicrobial peptides showing plausible activity against Mtb. These are the naturally synthesized endogenous oligopeptides constituting varying number of amino acids.

The active anti-tubercular peptides as TB therapeutics are discussed below.

4. Human immune cells associated anti-tubercular peptides

4.1. Cathelicidins

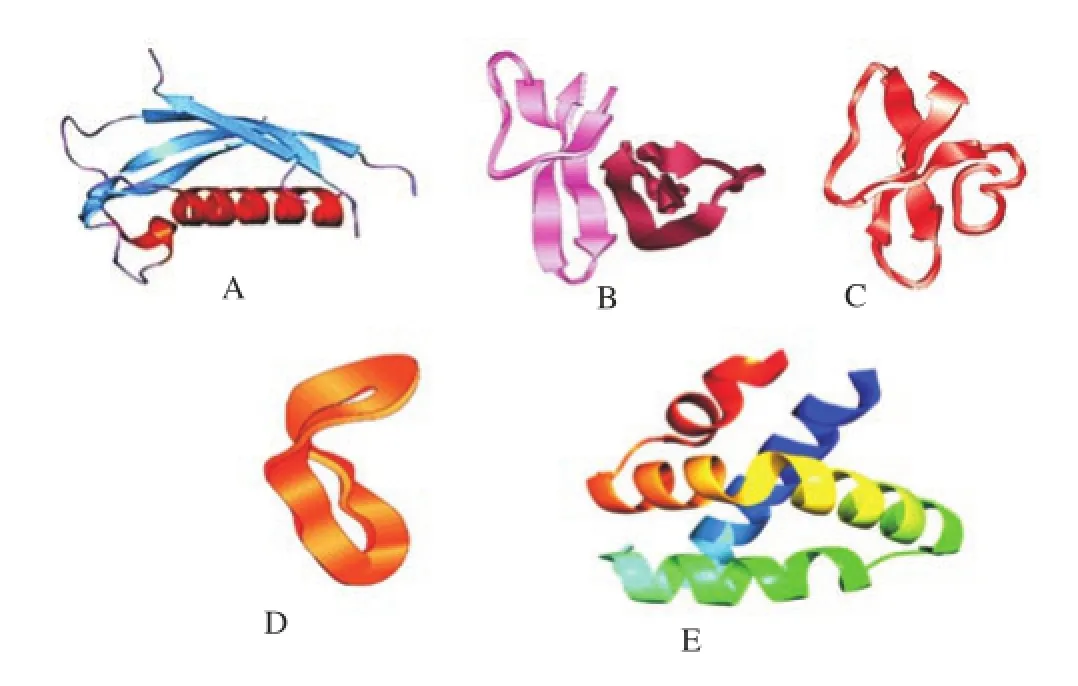

Cathelicidins are one of the most crucial human immune cells derived small cationic AMPs that play a considerable role in anti-tubercular activities. Cathelicidins belong to the host defense peptide that has a remarkable impact on the elimination of pathogens. Neutrophil granules store during prepropeptides stage of cathelicidins. These are the bipartite molecules and their mycobactericidal properties are due to the conserved N-terminal cathelin domain and a variable C-terminal domain (Figure 2A). However, the N-terminal cathelin domain is responsible for the intracellular storage part of cathelicidins. Cathelicidins confer the inducible expression in various cells and tissues which is regulated by several stimuli [12]. The activated neutrophils and epithelial cells are responsible for the synthesis of human cathelicidins antimicrobial peptides (hCAP18), then secreted into extracellular milieu. Proteinase-3 cleaves hCAP18 to form LL-37 peptide. Basically, LL-37 is the C-terminal of hCAP18 and taken up by neutrophils. The cathelicidins are induced by several stimuli, which then show antitubercular activity.

The intracellular survival of Mtb is inhibited by the exogenous addition of LL-37 or endogenous over-expression of LL-37 in macrophages. According to Sonawane et al [13], LL-37 exhibited anti-mycobacterial property in vitro as well as inside macrophages. LL-37 also contributes in the innate immune response against Mtb through the activation of G protein-coupled receptor N-formylpeptide receptor-like-1 (FPRL-1) [14]. LL-37 acts upon Mtb in vitro by creating pores or the disruption of cell membrane. On the other hand during in vivo study, LL-37 involves in Toll-like receptor (TLR) activation of monocytes to induce the inactivation of Mtb.

Previous reports manifestated that the synthetic peptide LL-37 had broad spectrum anti-tubercular activity in the epithelial cells of the lung and in bronchoalveolar lavage fluids. Additionally, LL-37 contributes in the inhibition of intracellular mycobacterium through NADPH oxidase 2-dependent process [15]. Similarly, LL-37 played an efficient role in the induction and maturation of autophagy pathways induced by vitamin D3 in human monocytes and regulated the transcriptional expression of the autophagyrelated genes such as beclin-1 and atg-5 via C/EBP-βand MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) activation [16]. The data clearly indicate that cathelicidins exert anti-tubercular properties as well as immunomodulatory potential of autophagy regulation during Mtb infection.

4.2. Defensins

Defensins are another human immune cell derived anti-tubercular peptides containing 29-35 amino acid residues and six highly conserved invariant cysteine residues. The defensins are major components of the innate immune response against Mtb, through an oxygen-independent mechanism [17]. Defensins show non-specific cytotoxicity to microorganisms. It constitutes a large portion ofthe pulmonary innate host defense system including respiratory epithelia and acts as signalling molecules for invading pathogens [18]. The precursors of defensins containβ-sheet-rich fold and six disulfide-linked cysteines.α-, β-, and θ-defensins (Figure 2B, 2C and 2D) are the sub-families of defensins based upon the structural differences. The gene expression study using microarray divulged that the effecter molecules of α-defensin were found to be upregulated in patients infected with TB [19]. During in vivo study, it was observed thatβ-defensins along with L-isoleucine showed enhanced anti-tubercular efficiency [20].

The human-defensins HBD-1 and HBD-2 are principally expressed at epithelial region and generally both have bactericidal property. HBD-2 can be transferred to mycobacterium-containing macrophage phagosomes during the infection and exert anti-tubercular activity. Currently, the role of HBD4 in the innate immune defense against mycobacteria has been studied. The up-regulation of HBD4 expression was observed in the presence of TLR2/1- mediated IL-1 β[21].

Human neutrophil peptide 1 (HNP-1), a type ofα-defensins found in the azurophilic granules of polymorphonuclear neutrophils showed significant activity against Mtb strain in a concentration-dependent manner with higher MIC (minimum inhibitory concentration) value than that of first-line anti-TB drugs. The microscopic observation showed that HNP-1 affected Mtb strain by permeabilization of cell membrane and forming pores [22].

Fgure 2. PDB structure of human immune cells associated antitubercular peptides. (A) Cathelicidins, (B)α- defensins, (C)βdefensins, (D)θ-defensins and (E) Granulysin.

4.3. Granulysin

Granulysin is a cationic glycoprotein that belongs to saposin-like protein family. It has close resemblance to NK-lysin, consisting of four helical bundle motifs, with the helices enriched with arginine and lysine residues (Figure 2E). The granulysin (15 kDa) can invade Mtb by entering into the human macrophages. Similarly, recombinant granulysin (15 kDa) were also known to kill Mtb by aerosol challenge and provided defense against TB [23]. Granulysins show anti-tubercular activity by acting upon mycobacterial membranes, leading to the disruption of synthetic liposomes and induction of apoptosis. However, the bacterial lysis is unaffected by the reduction of the disulfide bonds present in the peptides.

5. Human non-immune cells associated antitubercular peptides

Human non-immune cells such as hepatocytes, keratinocytes and eosinophils can also exert anti-tubercular activities through direct killing mechanisms by producing effective peptides. These peptides do not induce immunomodulatory activities. Some of the human non-immune cells associated anti-tubercular peptides are listed below:

5.1. Hepcidins

Hepcidin is a cationic amphipathic non-immune cells peptide produced in the liver. It is a key component of iron recycling by blocking iron absorption in response to iron overload and other stimuli. The production of hepcidin is markedly induced during the infection or any inflammatory conditions. Iron is essential for the survival of mycobacteria. Hepcidin mainly works by the regulation of transmembrane iron transport through binding with an iron exporter expressed in hepatocytes and macrophages, called as ferroportin [24]. Both the macrophage and the bacterium show competitive interaction for iron. In lieu of this, there is secretion of hepcidin by macrophage that restricts the growth of mycobacteria though blocking the release of the recycled iron from macrophages. It results into the subsequent reduction in the extracellular iron concentrations, thereby makes less available for microorganisms [24]. Thus, Mtb infections cause the expression of hepcidins in the macrophage and possess growth inhibition of the bacterial cell. Hepcidin could inhibit the growth of bacteria by damaging the structure of the mycobacteria. In general, the stimulation of macrophages synergistically with mycobacteria and Interferon-γinduced hepcidin mRNA and protein [25].

5.2. HCL2

HCL2 is another non-immune cells derived anti-tubercular peptide which is part of a seven-bundle helix of the human cytochrome c oxidase subunit3 (COX3) proteins. Its helical structure shows close resemblance with early secreted antigenic target (ESAT-6) protein. ESAT-6 and culture filtrate protein 10kDa (CFP10) proteins play critical roles in mycobacterial pathogenesis [26]. HCL2 could disrupt the heterodimeric interaction between ESAT-6 and CFP10 i.e. ESAT-6:CFP10 complex and affected the survival of Mtb significantly by disintegrating the cell wall and inhibiting the intracellular as well as extracellular bacterial growth.

5.3. Ubiquitin-derived peptide

Proteasomes are protein complexes inside eukaryotes and bacteria that have the ability to degrade damaged or unneeded proteins by a process called as proteolysis. Proteases favour this catalytic reaction. Peptides of shorter amino acids are obtained after the degradation process which is further used in synthesizing new proteins. Proteins are tagged with a small protein called as ubiquitin, catalyzed byubiquitin ligases. The prime function of the proteasome is to degrade proteins. The proteasome is essential for the pathogenicity of Mtb and therefore the Mtb proteasome are potential targets. Ubiquitin (Ub) is one of the post-translational modification proteins and usually acts as a signal for proteasome degradation. Ubiquitinderived peptides residing inside the lysosome contribute to the growth inhibition of Mtb [27]. Autophagy contributes a paramount role for the anti-tubercular potential of ubiquitin-peptides, because it induces the fusion of lysosome and Mtb-containing phagosome, enhancing the delivery of ubiquitin to lysosome [28].

Ub2 is an ubiquitin-derived peptide located in lysosome, exerting significant anti-tubercular activity. The mycobactericidal activity is due to the secondary structureβ-sheet of Ub2 that targets the bacterial membrane [29]. However, the sub-cellular localization studies demonstrated that Ub2 acts both on the bacterial membrane as well as the cytoplasm. The incorporation of Ub2 with bacterial membrane causes the membrane permeability and its exposure to adverse environments.

In another study the UbGR-ESAT-6 fusion DNA vaccine inoculation improved antigen-specific cellular immune responses, which can be useful against mycobacterial infection. BALB/c (bagg albino) mice were vaccinated with plasmid DNA encoding ESAT-6 protein, ubiquitin-fused ESAT-6 DNA vaccine (UbGR-ESAT-6), pcDNA3-ubiquitin and blank vector. The result demonstrated that Thl-polarized immune response was induced by ESAT-6 DNA vaccine immunization. There was enhancement in the production of Thl-type cytokine (IFN-gamma) and proliferative T-cell responses in mice immunized with UbGR-ESAT-6 fusion DNA vaccine, compared to non-fusion DNA vaccine. The relative ratio of IgG (2a) to IgG (l) and the cytotoxicity of T cells were also found to be increased [30].

6. Bacteria associated anti-tubercular peptides

Bacteriocins are ribosomally-synthesized microbicidal peptides produced by Gram-positive or Gram-negative bacteria. In the case of Gram-negative bacteria, most of the bacteriocins have been studied and characterized from Escherichia coli (E. coli) and other enterobacteria, and they are often divided into microcins (small peptides) or colicins (larger proteins). The lantibiotics (class I) and the non-lantibiotics (class II) are two major classes of bacteriocins obtained from Gram-positive bacteria. The lantibiotics are heat stable peptides constituting 19–38 amino acids with post-translational modifications including thioether-based ring structures (known as lanthionine or b-methyllanthionine). Nisin, subtilin, lacticin 3147 and thuricin CD are members of lantibiotics. The class II bacteriocins are cationic heat stable peptides constituting 25–60 amino acids. Lactic acid bacteria (LAB) are major producers of class II bacteriocins. Class III bacteriocins are less exploited large and heat-labile protein. The present necessity for the treatment of TB with novel target molecules has led to investigate the structural and functional analysis of bioactive peptides. To date, several bacteriocins have been studied with different structures and mechanisms. Few of the potential bacteriocins with anti-tubercular activities have been listed below:

6.1. Nisin

Nisin is the most characterized polycyclic antimicrobial protein produced by Lactococcus lactis (L. lactis) subsp. lactis. It represents the group I lantibiotics and consists of 34 amino acid residues, including the uncommon amino acids, viz. dehydroalanin, dehydrobutyrine and lanthionin. Nisin is the prototypical lantibiotic, ratified by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for its application as safe food additives. Moreover, it inhibits the synthesis of cell wall as well as creates pores in the bacterial cell membrane (CM) by binding to the peptidoglycan precursor, lipid II (Figure 3). Nisin exhibited the growth inhibition of Mycobacterium smegmatis (a non-pathogenic species of mycobacteria closely related to Mtb) and M. bovis-Bacillus Calmette Guerin (BCG), a vaccine strain of pathogenic M. bovis. The study demonstrated that 2.5 mg/mL of nisin was required to inhibit M. bovis-BCG. The peptide exhibited a concentration dependent decrease in internal ATP levels in M. bovis-BCG. In like manner, nisin reduced both the constituents of proton motive force in mycobacterium in a time and concentration dependent manner, establishing the growth inhibitory mechanism of nisin against mycobacteria, similar to foodborne pathogens. The hydrolysis and loss of intracellular ions resulted into the collapse of proton motive force and low intracellular ATP levels that would contribute to the antimycobacterial activity of nisin [31].

Figure 3. Bactericidal mechanism of Nisin, where I – Nisin, II – Pore formation, III – Lipid II.

According to the study of Carroll et al [32], novel bioengineered hinge derivatives such as nisin S, nisin T and nisin V displayed greater anti-tubercular activity against Mtb H37Ra using microtitre alamar blue assay (MABA). Among the derivatives investigated, Nisin S was found to be the most potent variant with anti-tubercular property, claiming the first report to illustrate an enhancement of efficacy by bioengineered bacteriocin against mycobacteria.

6.2. Lacticin 3147

Lacticin 3147 is another extensively characterized antimicrobial peptides that differs from nisin by virtue of requiring two peptides for optimal activity. Similar to nisin, Lacticin 3147 inhibits the synthesis of cell wall as well as creates pores in the bacterial cell membrane by binding to the peptidoglycan precursor, lipid II but distinguished from nisin both genetically as well as biologically.Lacticin 3147 is a critical bacteriocin produced by L. lactis subsp. lactis which is temperature and pH stable. In fact, it is a two-peptide (LtnA1 and LtnA2) lantibiotic at 1:1 ratio and effective at very low concentrations. Lacticin 3147 obtained from L. lactis showed growth inhibitory activity against Mtb H37Ra with MIC90 values of 7.5 μg/mL [33]. Dehydroascorbate (dha) reductase plays a major role in the conversion of L- alanine to D-alanine in lacticin 3147 and its inhibitory property is due to three D-alanines present in it [34]. The potential to create D-residues in this peptide may contribute in designing D-amino acid-containing peptides with anti-tubercular properties.

6.3. E50-52 and Lassomycin

E50-52, obtained from Enterococcus faecalis represents class IIa bacteriocins. The growth of mycobacterium was inhibited by E50-52 within macrophages at a non-cytotoxic concentration of 0.1 mg/L. In macrophages, the inhibition of mycobacterial growth was due to E50–liposome complex without affecting the macrophages membrane. During animal model study, E50–liposome was injected every 24 h for 5 consecutive days in the mouse which showed significantly increased life span of the infected mouse, indicating E50 as an adequate peptide in the treatment of MDR-TB [35].

Lassomycin is a cyclic peptide obtained from Lentzea kentuckyensis. In general, it targets ClpC1P1P2, which is an essential ATP-dependent protease responsible for the viability of mycobacteria [36]. Lassomycin binds to an acidic N-terminal pocket of ClpC1P1P2 and activates its ATPase activity, leading to uncoupling it from ClpP1P2 proteolysis. The uncoupling ATPase from proteolytic activity accounts for the mycobacterium growth inhibition property of lassomycin. Lassomycin is a unique AMPs because it activates the target enzyme rather than inhibiting it. Lassomycin showed anti-tubercular activity with an MIC of 0.8–3 mg/mL against MDR-TB and XDR-TB isolates [36], representing lassomycin as a promising anti-TB peptide.

6.4. Other bacteriocins and peptides

The capacity of bacteriocins to inhibit growth of Mtb had been investigated in limited reports. Sosunov et al [35] purified five different bacteriocins with antimycobacterial property which was assessed further using different models including in vitro mycobacterial cultures, in vitro infection of mouse macrophages and in vivo high-dose infection of inbred mice. Similarly, Lactobacillus plantarum and its bacteriocin (plantaricin 42) were successfully encapsulated in nano-fibers. The method may be incorporated for the successful delivery of bacteriocins to the specific sites of mycobacterium infections [37].

On the other hand two antimicrobial agents, lariatins A and B, isolated from Rhodococcus sp. K01-B0171 were found to be active against Mtb. The peptides consist of 18 and 20 L-amino acid residues with an internal linkage between theγ-carboxyl group and α-amino group of Glu8 and Gly1 respectively. Furthermore, the report demonstrated that the target molecule of lariatins might abide inside the biosynthetic steps of mycobacterial cell wall [38].

Aerococcus sp. ZI1 revealed its potentiality to inhibit the growth of Mycobacterium smegmatis used as a model to test the effect on Mtb. The reports demonstrated that Aerococcus sp. ZI1 produces proteinaceous inhibitory substances which should be purified and identified [39]. In the line of previous study, Hassi et al [40] and Guendouzi et al [41] reported Brevibacillus laterosporus and Bacillus sp. exhibiting antimycobacterial activity due to the production of proteinaceous substance respectively.

Nocardithiocin, a novel thiopeptide compound produced by Nocardia pseudobrasiliensis strain IFM 0757 showed a strong activity against rifampicin-resistant as well as sensitive Mtb strains with an MIC of 0.025 μg/mL. The study suggested that the Nocardia strains are potential sources of antimycobacterial compounds due to the production of a unique antibiotic, nocardithiocin [42].

In the line of TB therapy, a series of novel sansanmycin derivatives were designed, synthesized and appraised for their growth inhibitory potential against Mtb strain H37Rv with sansanmycin A (SSA) being the dominant. Among these analogs investigated, the potent compound exhibited an improved anti-tubercular activity with an MIC value of 8 μg/mL in comparison with SSA, suggesting the further exploration of these analogs for TB treatment [43]. In fact, sansanmycins belong to nucleosidyl–peptide antibiotics, produced by Streptomyces sp. Additionally, sansanmycin F and G were also assessed for their inhibitory activity against Mtb H37Rv, based upon the alamar blue microplate assay, with significant MIC value of 16 μg/ mL[44].

7. Fungi derived anti-tubercular peptides

Apart from bacteria, fungi are also potential sources of novel bioactive compounds or peptides. A large pool of peptides is secreted by fungi but only few of them being bioactive, especially as anti-tubercular peptides. Large-scale production of these bioactive fungal peptides may prove their biotechnological potential for the growth inhibition of Mtb and may establish their significant role as a valuable, although relatively unexplored source of TB therapy.

7.1. Calpinactam

Calpinactam (molecular formula-C38H57N9O8) is an antimycobacterial hexapeptide with a caprolactam ring at its C-terminal, originally isolated from the fungus Mortierella alpina. Koyama et al [45] reported the isolation of calpinactam from the culture broth of Mortierella alpine FKI-4905 by solvent extraction method, octadecyl silane column chromatography and preparative HPLC. Calpinactam was found to be active against Mtb with an MIC value of 12.5 μg/mL. The calpinactam might be responsible to inhibit the mycobacterial growth by interrupting the biosynthetic steps of cell wall. However, the mechanisms of action of calpinactam against Mtb are yet to be investigated in depth.

7.2. Trichoderin

Pruksakorn et al [46] isolated three new aminolipopeptides, namely Trichoderins A, A1 and B from marine sponge-derived fungus of Trichoderma sp. These peptides exhibited their antimycobacterial activity against active and dormant bacilli, Mtb H37Rv under both aerobic growth conditions and dormancy-inducing hypoxic conditions, with MIC values ranging from 0.02 to 2.0 μg/mL. The anti-tubercular peptide inhibited the bacterial growth by impeding the mode of ATP synthesis.

7.3. Bisdethiobis(methylsulfanyl) apoaranotin and Cordycommunin

Bisdethiobis(methylsulfanyl) apoaranotin was isolated from the fungus Aspergillus terreus BCC 4651. The bioactive peptide exhibited the growth inhibitory property of Mtb H37Ra with an MIC value of 1.56 μg/mL[47]. On the other hand, cordycommunin (a cyclodepsipeptide, C43H69N7O11) was isolated from the insect pathogenic fungus Ophiocordyceps communis BCC16475. The study showed that the cordycommunin inhibited the growth of Mtb H37Ra with a significant MIC value of 15 μM [48].

In view of the instant demand to develop new peptide derived drugs as an alternative to existing TB therapy, several fungal strains have been screened for their antimycobacterial activity. During 2000-2005, only few fungal metabolites with promising antitubercular properties had been reported. Among those bioactive metabolites, hirsutellones A–D, isolated from Hirsutella nivea, inhibited the growth of Mtb significantly at MIC values ranging from 0.78 to 3.12 μg/mL [49]. In the line of searching most active anti-tubercular peptides from fungi, a total of 82 fungal extracts were screened against Mtb in order to investigate the potential fungi with antimycobacterial characteristics [50]. Results exhibited that Cylindrocarpon sp. XH9B, Fusarium sp. TA54, Fusarium XH1Ga, Gliocladium penicillioides TH04 and TH21, Gliocladium sp. TH16, Kutilakesa sp. MR46, and Verticillium sp. TH28 had significant antitubercular activity with MIC values ranging from 1.56 to 25 μg/mL.

8. Venom derived anti-tubercular peptides

The disquieting incidence of TB in immunocompromised people has emphasized the researchers to develop novel antibiotics from diverse sources for the growth inhibition of Mtb. From this point of view, despite the potential anti-tubercular peptides obtained from prokaryotes and eukaryotes, it is quite interesting that venoms from reptiles, arthropods etc. had also been investigated for the treatment of TB. Relatively there are very few reports on the venoms associated with anti-tubercular activity to date. In general, snake venoms are complex mixtures of bioactive proteins and polypeptides. About 90% of venom's dry weight constitutes proteinaceous substances [51]. The venomous proteins are of biological concern due to their distinct and specific pharmacological and physiological effects, demonstrating the significance of snake venom proteins as valuable tools for drug development.

Xie et al [52] successfully investigated the in vitro study of vgf-1 (obtained from Naja atra) against multi-drug resistant Mtb. The MIC value of this small peptide was found to be 8.5 mg/L using Bactec TB-460 radiometric method. The study also recommended the in vivo evaluation of vgf-1 in order to understand the potential role of this peptide against Mtb for the possible treatment of MDR-TB. In line of this, Bhunia et al [53] demonstrated in vitro activities of venoms of Naja naja, Bungarus fasciatus, Daboia russelli russelli and Naja kaouthia against MDR-TB strains.

Pandinin 2 (Pin2) is a 24-residueα-helical antimicrobial peptide characterized from the venom of Pandinus imperator (a scorpion). It has a central proline residue that forms a structural ‘‘kink'' linked to its pore-forming activity towards human RBC. The ‘‘kink'' is a structural characteristic of some cationic antimicrobial peptides that confer them high pore-forming abilities, for example melittin, alamethicin and pardaxin. The presence of a proline ‘‘kink'' in those peptides was correlated to a high antimicrobial activity. According to the report of Rodriguez et al [54], the residue Pro14 of Pin2 was substituted and flanked using glycine residues (P14G and P14GPG) based on the low haemolytic activities of antimicrobial peptides with structural motifs Gly and GlyProGly such as magainin 2 and ponericin G1 respectively. The short Pin2 variants named Pin2 (14) and Pin2 (17) showed better growth inhibitory activity at molar concentrations against Mtb than that of the conventional antibiotics such as ethambutol, isoniazid and rifampicin.

9. Anti-tubercular peptides from other sources

Furthermore, Microcystins are cyclic heptapeptides that consists of seven amino acids (five non-protein and two protein amino acids). Microcystins are chemically related cyclic peptides and most commonly studied group of cyanotoxins. Ramos et al [55] investigated the antimycobacterial activity of Microcystis aeruginosa extract and microcystin using resazurin microtiter assay against Mtb. The hexanic extract of Microcystis aeruginosa (RST 9501 strain) showed activity against Mtb strains with MIC values between 1.93 μM and 0.06 μM.

Streptomyces from Lienardia totopotens contained a new and known spirotetronate polyketides called as lobophorins with varying degrees of bioactivity against Mtb and found that the lobophorins are relatively potent candidate for TB therapy [56]. Basically, lobophorins belong to a family of bacterial spirotetronates.

In another report, PK34 from bacteriophage showed Mtb growth inhibitory activity with an MIC value of 50 μg/mL and also exerted strong anti-mycobacterial activity in vivo [57]. PK34 could interact to trehalose-6, 6-dimycolate (TDM), which is a major target for anti-mycobacterial effect. The receptor affinity and biological characteristics of peptides are due to their secondary structure. The rational design can be sufficient to endow antibacterial activity and to circumvent drawback effects in this potential therapeutic agent[58]. Thus, understanding the molecular mechanisms and potential of above mentioned anti-tubercular peptides in response to Mtb will contribute in the designing and development of new therapeutic drugs. But the there are several factors to consider before designinga potential drug from anti-tubercular peptides. The selected peptides have common properties i.e. antimycobacterial potential but they differ from each other in several physiochemical properties such as sequence length, net charge, amphipathicity, hydrophobicity and solubility. These parameters will help to induce the antimycobacterial activities and target specificity of peptides. In fact, understanding the structure activity relationships may contribute in designing a novel anti-tubercular drug with improved efficiency.

10. Current scenario to combat Mtb: Where do we stand now?

In spite of tremendous efforts and monetary substratum by the sundry institutions of various countries to combat TB, the disease still remains a leading burden for the world during the past two decades due to the emerging resistance property of Mtb against first-line drugs, especially isoniazid and rifampicin. According to WHO [59] report, expert management and frequent monitoring are required to cure TB. At present, the treatment for MDR-TB are time consuming that lasts for 18 to 24 months or even longer. Additionally, MDR-TB craves the use of second-line drugs too that are not only expensive but also produces excruciating side effects. Furthermore, second-line drugs are much more toxic and exorbitant costlier than the first-line regimen. There is drastic increase in the proportion of drug resistant Mtb in last few years because of the poor life style, alcohol abuse, poverty and malnutrition. As a result of poor treatment outcomes, the disease became a major concern worldwide, particularly in developing nations. Moreover, at present moment, India, China, the Russian Federation and South Africa alone account for nearly 60% of the world's MDR-TB [1] that represents TB a human danger and public health issue globally.

According to the latest report of WHO [60], there are increased total counts for new TB cases globally than in last few years. In spite of the recent advances and the fact for curing tuberculosis, the disease remains one of the world's deadliest threats. The medications forthe treatment of TB can also lead to other serious health issues, such as kidney failure, liver, or heart disorder, loss of vision or hearing, psychosis and most importantly HIV infection. Worldwide, 12% of the 9.6 million new TB cases are found to be HIV-positive. In fact, HIV infection impels the risk of TB infection on exposure, progression from latent infection to active, and finally a risk of mortality if not treated both TB and HIV in time.

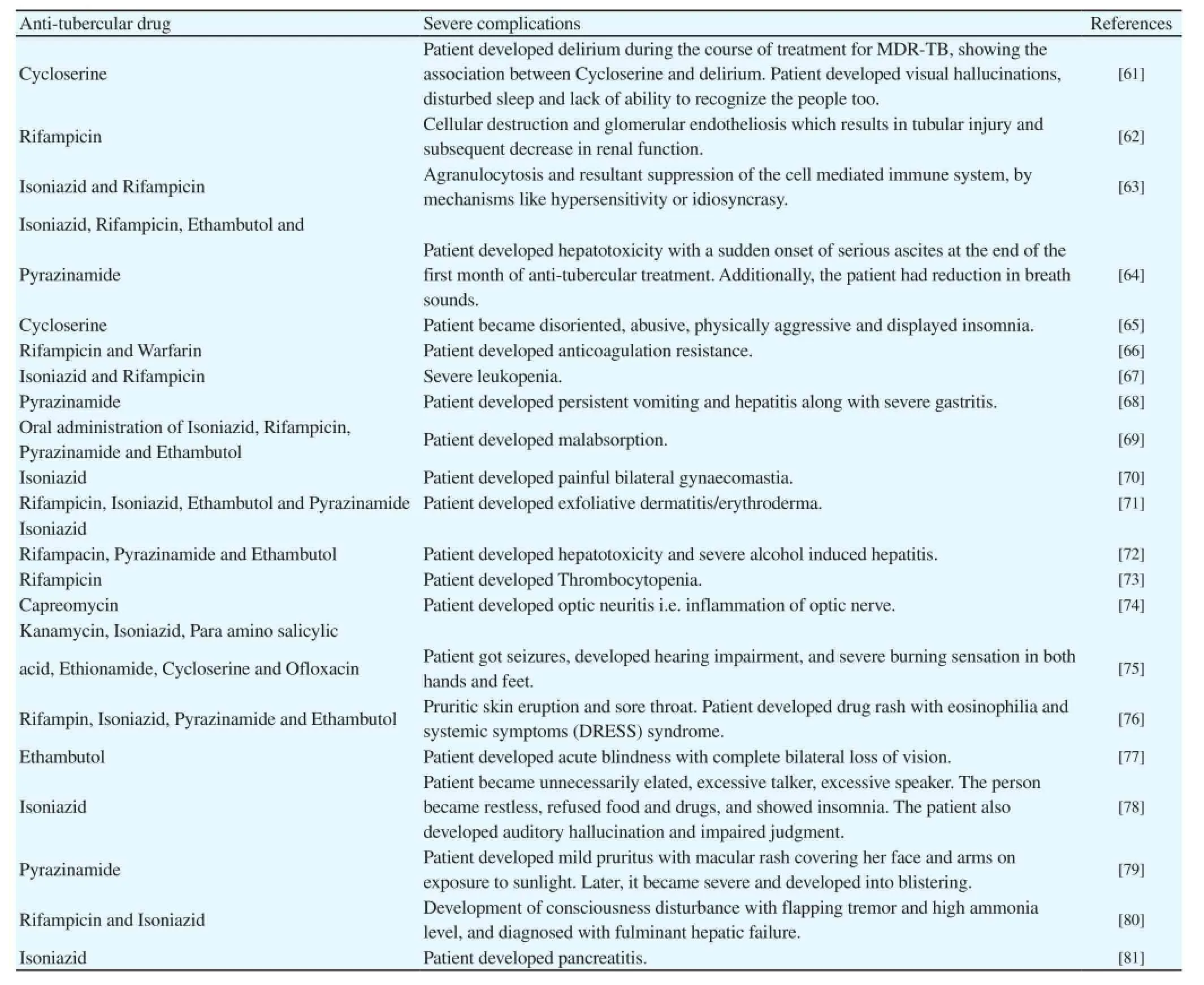

Table 1 Currently available anti-tubercular drugs and their severe complications.

At present, the treatment of TB has resurged due to its expensive therapy, emerging rate of MDR-TB and most importantly the side effects of currently available drugs worldwide. One side of the coin shows the increased frequency of Mtb in HIV infected people that raised a great concern across the globe. In addition to this, another side of the coin deals with the several cases worldwide that reported the negative impact of currently available anti-tubercular drugs on human health. The regimens and treatment of TB continues to remain a challenging course with a variety of complications. In fact, the side effects of the most commonly used anti-tubercular drugs may be mild as well as fatal. Table 1 enlists the several cases reporting the complications of presently available anti-tubercular drugs that might be due to their direct toxicity or immunologic mechanisms.

The incidence of serious adverse reactions of above mentioned anti-tubercular drugs during the treatment of TB has attracted the attention of worldwide researchers to find the effective replacement of existing therapy with null side effects from other inexpensive sources. The bioactive anti-tubercular peptides of various origins may be an expectant approach to combat Mtb. Such an effective approach may avoid not only the existing problems of side effects associated with high dose therapy of TB but also exemplify its superiority to the currently available expensive treatment.

11. Clinical trials status of currently available antitubercular drugs

In last few decades, several anti-tubercular agents have been examined for their effectiveness towards drug-susceptible and drugresistant TB. Few of the drugs developed from those anti-tubercular agents after advanced screening process are scheduled for clinical trials in 2016. At present, very few anti-tubercular agents are in preclinical and clinical development. In fact, the major purpose of these clinical studies is to assess the non-toxicity and efficacy of these drugs as standard regimens for TB treatment.

Ahsan et al [82] and Palomino and Martin [83] updated an elaborate report on the drugs currently in clinical trials and also familiarize few new compounds under pre-clinical development. Most of these anti-tubercular drugs under different phases of clinical trials show antimycobacterial property against Mtb by inhibiting bacterial cell wall as well as protein synthesis. Rifapentine and TMC-207 are DNA dependent RNA polymerase and ATPase synthesis inhibitor respectively. PBTZ 169 binds with decaprenylphosphoryl- beta-D-ribose 2-epimerase and inhibits the growth of Mtb. TBI-166 targets bacterial membrane and ion transport system. SQ-641 inhibits Translocase-1. On the other hand CPZEN-45, DC-159a and Q-203 targets WecA, GyrA activity and cytochrome bc1 complex of Mtb respectively[83].

In last four decades, among the clinically trialled drugs, only TMC207 (now commercialized as bedaquiline) has received FDA approval for the treatment of MDR-TB after Phase II trials. Due to the failure of most of the drugs for TB therapy in clinical trial studies and severe complications of currently available anti-tubercular drugs to the patients, it is the right time to undertake a critical step in discovering novel anti-tubercular drugs/agents from most suitable sources. Keeping in view of the previous findings, antitubercular peptides have created a new prospect to challenge MDR-and XDR-TB. The newly isolated and characterized anti-tubercular peptides from various sources may be utilized in lieu of the existing drugs by dint of their novel mode of action that may contribute to combat MDR-TB. However, the non-toxicity properties of the antitubercular peptides to the patients, superiority to currently available drugs and preliminary efficacy outcome would be crucial factors during different phases of clinical trial studies.

TB-Platform for Aggregation of Clinical TB Studies (TB-PACTS) is the newly launched data-sharing stage for TB clinical trial studies that makes these data publicly available. It is a new tool that provides a larger sample size, an opportunity to analyze specific populations, and to find commonalities that were not picked up in the single trials. This tool is valuable in the fight against TB. In fact, TBPACTS collaborate with Critical Path Institute (C-Path) as well as St. George's University of London.

12. Anti-tubercular peptides for the treatment of TB: Why do we need this?

New anti-tubercular drugs of distinct origin are desperately required not only due to the complexity and severe side effects of the current TB drug regimes but also because of the emerging worriment of MDR-or XDR-TB. In last few years, an urgent obligation for the discovery of new TB drugs has heightened due to the negative interaction between anti-tubercular drugs and anti-retroviral drugs administrated to HIV positive person. Present-day strategies for TB therapies are time consuming with adverse concomitant medications due to the development of drug-resistant mycobacterial strains. The lack of novel mode of anti-tubercular properties of existing drugs is another major issue for the emergence of drug-resistant bacteria. The anti-tubercular peptides have multiple roles, especially direct growth inhibition of Mtb and immune-modulation activity during the bacterial infection. The lengthy treatment period, development of MDR- and XDR-TB strains, severe side effects from most of the existing antimycobacterial drugs, and challenges in combating TB patients co-infected with HIV underlie the indispensable obligation for the implementation of new anti-tubercular peptides from various provenances. Due to the conceivable antimycobacterial property, the anti-tubercular peptides may be exploited substantially to cure TB in a relatively shorter time period and undoubtedly it can be consideredauspicious candidates for the development of efficacious drugs in future due to their specific mode of action.

13. Concluding remarks and future perspective

The alarming increase in MDR- or XDR-TB infections are a deliberate threat to mankind globally that triggered the urgency to develop novel anti-tubercular agents. Comprehensive literatures on the anti-tubercular properties of peptides from diversiform sources have shown an idealistic approach towards the TB cure. Peptides associated with human immune cells, human non-immune cells, bacteria, fungi, venoms and other sources have been demonstrated to be emphatic anti-tubercular agents. These natural peptides with their unique mechanisms of action are remarkable arenas for future drug development. An insight into the correlation between peptide structure and molecular mode of action will lead to design novel anti-tubercular drugs that might overcome the complications of existing drugs.

Furthermore, novel identified peptides conjugating to broad spectrum antibiotics can be another practice towards the enhancement of mycobactericidal property. Interestingly, antimicrobial agents at mild concentrations induce total protein production in microorganisms by regulating transcription mechanism [84]. Synthesizing novel anti-tubercular proteins or short peptides in microorganisms under mild stress conditions of certain antimicrobials can be a dynamic formula to conquer MDR-or XDR-TB with novel mode of growth inhibitory action. From 2016, it is a goal to reduce the number of TB deaths by 80-90% in the next thirty to forty years and to ensure the eradication of TB in a few decades by adapting new strategies and developing novel drugs, especially from anti-tubercular peptides in order to escape from the era of multi-drug resistant Mtb. Further understanding the mode of action, non-toxicity and immunogenicity of the newly discovered anti-tubercular peptides will act as decisive armours and will guide us to develop puissant anti-TB drugs in future.

Conflict of interest statement

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by Maulana Azad National Fellowship (F1-17.1/ 2015-16/MANF-2015-17-BIH-60730), University Grants Commission, Delhi, India.

References

[1] WHO.Global tuberculosis report 2012. Geneva, Switzerland:WHO;2012.

[2] Kwan CK, Ernst JD. HIV and tuberculosis: A deadly human syndemic. Clin Microbiol Rev 2011; 24(2): 351-376.

[3] Welin A, Raffetseder J, Eklund D, Stendahl O, Lerm M. Importance of phagosomal functionality for growth restriction of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in primary human macrophages. J Innate Immun 2011; 3(5): 508-518.

[4] Li W, Xie J. Role of mycobacteria effectors in phagosome maturation blockage and new drug targets discovery. J Cell Biochem 2011; 112(10): 2688-2693.

[5] Mishra AK, Driessen NN, Appelmelk BJ, Besra GS. Lipoarabinomannan and related glycoconjugates: structure, biogenesis and role in Mycobacterium tuberculosis physiology and host–pathogen interaction. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2011; 35(6): 1126-1157.

[6] Indrigo J, Hunter Jr RL, Actor JK. Cord factor trehalose 6, 6’-dimycolate (TDM) mediates trafficking events during mycobacterial infection of murine macrophages. Microbiology 2003; 149(8): 2049-2059.

[7] Camacho LR, Constant P, Raynaud C, Laneelle MA, Triccas JA, Gicquel B, et al. Analysis of the phthiocerol dimycocerosate locus of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Evidence that this lipid is involved in the cell wall permeability barrier. J Biol Chem 2001; 276:19845–19854.

[8] Kusner DJ, Barton JA. ATP stimulates human macrophages to kill intracellular virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis via calcium-dependent phagosome lysosome fusion. J Immunol 2001; 167(6): 3308-3315.

[9] Malik ZA, Thompson CR, Hashimi S, Porter B, Iyer SS, Kusner DJ. Cutting edge: Mycobacterium tuberculosis blocks Ca2+signaling and phagosome maturation in human macrophages via specific inhibition of sphingosine kinase. J Immunol 2003; 170(6): 2811-2815.

[10] Flynn JAL, Chan J. Immunology of tuberculosis. Annu Rev Immunol 2001; 19(1): 93-129.

[11] Lamkanfi M, Dixit VM. Manipulation of host cell death pathways during microbial infections. Cell Host Microbe 2010; 8(1): 44-54.

[12] Zanetti M. Cathelicidins, multifunctional peptides of the innate immunity. J Leukoc Biol 2004; 75(1): 39-48.

[13] Sonawane A, Santos JC, Mishra BB, Jena P, Progida C, Sorensen OE, et al. Cathelicidin is involved in the intracellular killing of mycobacteria in macrophages. Cell Microbiol 2011; 13(10): 1601-1617.

[14] Martineau AR, Wilkinson KA, Newton SM, Floto RA, Norman AW, Skolimowska K, et al. IFN-gamma- and TNF-independent vitamin D-inducible human suppression of mycobacteria: The role of cathelicidin ll-37. J Immunol 2007; 178(11): 7190-7198.

[15] Yang CS, Shin DM, Kim KH, Lee ZW, Lee CH, Park SG, et al. NADPH oxidase 2 interaction with TLR2 is required for efficient innate immune responses to mycobacteria via cathelicidin expression. J Immunol 2009; 182(6): 3696-3705.

[16] Yuk JM, Shin DM, Lee HM, Yang CS, Jin HS, Kim KK, et al. Vitamin D3 induces autophagy in human monocytes/macrophages via cathelicidin. Cell Host Microbe 2009; 6(3): 231-243.

[17] Liu PT, Modlin RL. Human macrophage host defense against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Curr Opin Immunol 2008; 20(4): 371-376.

[18] Ganz T. Antimicrobial polypeptides in host defense of the respiratory tract. J Clin Invest 2002; 109(6): 693-697.

[19] Jacobsen M, Repsilber D, Gutschmidt A, Neher A, Feldmann K, Mollenkopf HJ, et al. Candidate biomarkers for discrimination between infection and disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Mol Med (Berl) 2007; 85(6): 613-621.

[20] Rivas-Santiago CE, Rivas-Santiago B, Leon DA, Castaneda-DelgadoJ, Pando RH: Induction of beta-defensins by l-isoleucine as novel immunotherapy in experimental murine tuberculosis. Clin Exp Immunol 2011; 164(1): 80-89.

[21] Gutierrez MG, Master SS, Singh SB, Taylor GA, Colombo MI, Deretic V. Autophagy is a defense mechanism inhibiting BCG and Mycobacterium tuberculosis survival in infected macrophages. Cell 2004; 119(6): 753-766.

[22] Zhu LM, Liu CH, Chen P, Dai AG, Li CX, Xiao K. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis is associated with low plasma concentrations of human neutrophil peptides 1-3. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2011; 15(3): 369-374.

[23] Okada M, Kita Y, Nakajima T, Kanamaru N, Hashimoto S, Nagasawa T, et al. Novel therapeutic vaccine: Granulysin and new DNA vaccine against tuberculosis. Hum Vaccin 2011; 7: S60-67.

[24] Nemeth E, Ganz T. The role of hepcidin in iron metabolism. Acta Haematol 2009; 122(2-3): 78-86.

[25] Sow FB, Florence WC, Satoskar AR, Schlesinger LS, Zwilling BS, Lafuse WP. Expression and localization of hepcidin in macrophages: a role in host defense against tuberculosis. J Leukoc Biol 2007; 82(4): 934-945.

[26] Yang H, Chen HZ, Liu ZH, Ma H, Qin LH, Jin RL, et al. A novel B-cell epitope identified within Mycobacterium tuberculosis CFP10/ESAT-6 protein. PLoS One 2013; 8(1): e52848.

[27] Purdy GE, Russell DG. Lysosomal ubiquitin and the demise of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Cell Microbiol 2007; 9(12): 2768-2774.

[28] Alonso S, Pethe K, Russell DG, Purdy GE. Lysosomal killing of Mycobacterium mediated by ubiquitin-derived peptides is enhanced by autophagy. Proct Natl Acad Sci USA 2007; 104(14): 6031-6036.

[29] Foss MH, Powers KM, Purdy GE. Structural and functional characterization of mycobactericidal ubiquitin-derived peptides in model and bacterial membranes. Biochemistry 2012; 51(49): 9922-9929.

[30] Wang QM, Kang L, Wang XH. Improved cellular immune response elicited by a ubiquitin-fused ESAT-6 DNA vaccine against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbiol Immunol 2009; 53(7): 384-390.

[31] Chung HJ, Montville TJ, Chikindas ML. Nisin depletes ATP and proton motive force in mycobacteria. Lett Appl Microbiol 2000; 31(6): 416-420.

[32] Carroll J, Field D, O'Connor PM, Cotter PD, Coffey A, Hill C, et al. Gene encoded antimicrobial peptides, a template for the design of novel anti-mycobacterial drugs. Bioeng Bugs 2010;1(6): 408–412.

[33] Carroll J, Draper LA, O'Connor PM, Coffey A, Hill C, Ross RP, et al. Comparison of the activities of the lantibiotics nisin and lacticin 3147 against clinically significant mycobacteria. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2010; 36(2): 132-136.

[34] Suda S, Lawton EM, Wistuba D, Cotter PD, Hill C, Ross RP. Homologues and bioengineered derivatives of ltnj vary in ability to form d-alanine in the lantibiotic lacticin 3147. J Bacteriol 2012; 194(3): 708-714.

[35] Sosunov V, Mischenko V, Eruslanov B, Svetoch E, Shakina Y, Stern N, et al. Antimycobacterial activity of bacteriocins and their complexes with liposomes. J Antimicrob Chemoth 2007; 59: 919-925.

[36] Gavrish E, Sit CS, Cao SG, Kandror O, Spoering A, Peoples A, et al. Lassomycin, a ribosomally synthesized cyclic peptide, kills Mycobacterium tuberculosis by targeting the ATP-dependent protease ClpC1P1P2. Chem Biol 2014; 21(4): 509-518.

[37] Heunis TDJ, Botes M, Dicks LM. Encapsulation of Lactobacillus plantarum 423 and its bacteriocin in nanofibers. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins 2010; 2(1): 1867-906.

[38] Iwatsuki M, Tomoda H, Uchida R, Gouda H, Hirono S, Oh mura S. Lariatins, antimycobacterial peptides produced by Rhodococcus sp. K01-B0171, have a lasso structure. J Am Chem Soc 2006; 128(23): 7486-7491.

[39] Zahir I, Houari A, Iraqui M, Ibnsouda S. Aerococcus sp. with an antimycobacterial effect. Afr J Biotechnol 2011; 10(83): 19473-19480.

[40] Hassi M, Guendouzi SE, Haggoud A, David S, Ibnsouda S, Houari A, et al. Antimycobacterial activity of a Brevibacillus laterosporus strain isolated from a moroccan soil. Braz J Microbiol 2012; 43 (4): 1516-1522.

[41] Guendouzi SE, Suzanna D, Hassi M, Haggoud A, Souda SI, Houari A, et al. Isolation and identification of Bacillus strains with antimycobacterial activity. Afr J Microbiol Res 2011; 5(21): 3468-3474.

[42] Bagley MC, Dale JW, Merritt EA, Xiong X. Thiopeptide antibiotics. Chem Rev 2005; 105(2): 685-714.

[43] Li Y, Xie Y, Du N, Lu Y, Xu H, Wang B. Synthesis and in vitro antitubercular evaluation of novel sansanmycin derivatives. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2011; 21(22): 6804–6807.

[44] Xie Y, Xu H, Sun C, Yu Y, Chen R. Two novel nucleosidyl-peptide antibiotics:sansanmycin F and G produced by Streptomyces sp SS. J Antibiot 2010; 63: 143–146.

[45] Koyama N, Kojima S, Nonaka K, Masuma R, Matsumoto M, O mura S, et al. Calpinactam, a new anti-mycobacterial agent, produced by Mortierella alpina FKI-4905. J Antibiot 2010; 63(4): 183–186.

[46] Pruksakorn P, Arai M, Kotoku N, Vilcheze C, Baughn AD, Moodley P, et al. Tri-choderins, novel aminolipopeptides from a marine sponge-derived Trichoderma sp., are active against dormant mycobacteria. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2010; 20(12): 3658–3663.

[47] Haritakun R, Rachtawee P, Komwijit S, Nithithanasilp S, Isaka M. Highly conjugate dergostane-type steroids and aranotin-type diketopiperazines from the fungus Aspergillus terreus BCC 4651. Helvetica Chimica Acta 2012; 95(2): 308–313.

[48] Haritakun R, Sappan M, Suvannakad R, Tasanathai K, Isaka M. An antimycobacterial cyclodepsipeptide from the entomopathogenic fungus Ophiocordyceps communis BCC 16475. J Nat Prod 2010; 73(1): 75–78.

[49] Rateb ME, Ebel R. Secondary metabolites of fungi from marine habitats. Nat Prod Rep 2011; 28(2): 290–344.

[50] Gamboa-Angulo M, Molina-Salinas GM, Chan-Bacab M, Peraza-Sánchez SR, Heredia G, de la Rosa-García SC, et al. Antimycobacterial and antileishmanial effects of microfungi isolated from tropical regions in Mexico. Parasitol Res 2013; 112(2): 559-566.

[51] Aarti C, Khusro A. Snake venom as Anticancer agent- current perspective. Int J Pure Appl Biosci 2013; 1(6): 24-29.

[52] Xie JP, Yue J, Xiong YL, Wang WY, Yu SQ, Wang HH, et al. In vitro activities of small peptides from snake venom against clinical isolates of drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Int J Antimicrobiol Agents 2003;22(2): 172-174.

[53] Bhunia SK, Sarkar M, Dey S, Bhakta A, Gomes A, Giri B, et al. In vitro activity screening of snake venom against multi drug resistant tuberculosis. J Trop Dis 2015; 4(192): 1-4.

[54] Rodriguez A, Villegas E, Montoya-Rosales A, Rivas-Santiago B, Corzo G. Characterization of antibacterial and hemolytic activity of synthetic Pandinin 2 variants and their inhibition against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS One 2014; 9(7): e101742.

[55] Ramos DF, Matthiensen A, Colvara W, Souza de Votto AP, Trindade GS, da Silva PEA, et al. Antimycobacterial and cytotoxicity activity of microcystins. J Venom Anim Toxins Incl Trop Dis 2015; 21(9): 1-7.

[56] Lin Z, Koch M, Pond CD, Mabeza G, Seronay RA, Concepcion GP, et al. Structure and activity of lobophorins from a turrid mollusk-associated Streptomyces sp. J Antibiot 2014; 67:121–126.

[57] Wei L, Wu J, Liu H, Yang HL, Rong MQ, Li DS, et al. A mycobacteriophage-derived trehalose-6,6 '-dimycolate-binding peptide containing both antimycobacterial and anti-inflammatory abilities. Faseb J 2013; 27: 3067-3077.

[58] Jamieson AG, Boutard N, Sabatino D, Lubell WD. Peptide scanning for studying structure-activity relationships in drug discovery. Chem Biol Drug Des 2013; 81(1): 148–165.

[59] WHO. WHO global tuberculosis report 2014[Online]. Available at: http:// www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en.

[60] WHO. Global tuberculosis report 2015. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2015.

[61] Saraf G, Akshata JS, Kuruthukulangara S, Thippeswamy H, Reddy SK, Buggi S, et al. Cycloserine induced delirium during treatment of multidrug resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB). Egyptian J Chest Dis Tuberc 2015; 64(2): 449–451

[62 Beebe A, Seaworth B, Patil N. Rifampicin-induced nephrotoxicity in a tuberculosis patient. J Clin Tuberc Mycobacterial Dis 2015; 1: 13–15.

[63] Bhattacharyya S, Kumar D, Gupta P, Banerjee G, Singh M. Subcutaneous abscess caused by Nocardia asteroides in a patient with pulmonary tuberculosis: Case report and review of the literature. J Evolution Med Dent Sci 2012; 1(6): 913-915.

[64] Atmaca HU, Akba F, Demir P, Uysal BB, Altınok R, Erdenen F. An Antitubercular therapy induced-hepatotoxicity case with diffuse Ascites. Istanbul Med J 2013; 14: 215-217.

[65] Otu AA, Offor JB, Ekpor IA, Olarenwaju O. New-onset psychosis in a multi-drug resistant tuberculosis patient on Cycloserine in Calabar, Nigeria: A case report. Trop J Pharm Res 2014; 13(2): 303-305.

[66] Martins MAP, Reis AMM, Sales MF, Nobre V, Ribeiro DD, Rocha MOC. Rifampicin-warfarin interaction leading to macroscopic hematuria: A case report and review of the literature. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol 2013; 14(27): 1-5.

[67] Bidarimath BC, Somani R, Umeshchandra CH, Tharangini SR, Sajid. Agranulocytosis induced by anti-tubercular drugs, Isoniazid (INH) and Rifampicin (R)-A rare case report. Int J Pharmacol Res 2016; 6(2): 84-85.

[68] Yasaswini B, James A, Sudhakar R, George MK, Ashok Kumar TR, Sivakumar T. Pyrazinamide induced multiple adverse drug reactions: A case report. World J Pharm Pharm Sci 2015; 4(3): 1317-1320.

[69] Bento J, Bento J, Duarte R, Brito MC, Leite S, Lobato MR, et al. Malabsorption of antimycobacterial drugs as a cause of treatment failure in tuberculosis – BMJ Case Rep 2010; 2010. pii: bcr1220092554. doi: 10.1136/bcr.12.2009.2554.

[70] Garg R, Vaibhav, Mehra S, Prasad R. Isoniazid induced Gynaecomastia: A case report. Indian J Tuberc 2009; 56(1): 51-54.

[71] Dua R, Sindhwani G, Rawat J. Exfoliative dermatitis to all four first line oral anti-tubercular drugs. Indian J Tuberc 2010; 57: 53-56.

[72] Amer K, Mir ShoebUlla A, Aamir SA, Nematullah K, Ihtisham S, Maazuddin M. Anti-tuberculosis drug - induced hepatitis – A case report. Indian J Pharm Practice 2013; 6(2): 65-67.

[73] Dinesh Prabhu R, Vikneswaran G, Lepcha C, Singh NT. Antituberculosis Therapy (ATT) induced thrombocytopenia: A case report. Int J Pharmacol Clin Sci 2013; 2(4): 126-128.

[74] Magazine R, Pal M, Chogtu B, Nayak V. Capreomycin-induced optic neuritis in a case of multidrug resistant pulmonary tuberculosis. Indian J Pharmacol 2010; 42(4): 247-248.

[75] Verma S, Mahajan V. Multiple side effects of second line antitubercular therapy in a single patient. Internet J Pulm Med 2007;9(2): 1-3.

[76] Kaswala DH. Drug rash with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms syndrome due to Anti-TB medication. J Family Med Primary Care 2013; 2(1): 83-85.

[77] Kodan P, Kariappa A, Hejamady MI. Ethambutol induced acute ocular toxicity: A rare case report. J Med Trop 2014; 16(1):32-34.

[78] Oninla SO, Oyedeji GA, Oninla OA, Gbadebo-Aina JO. Isoniazidinduced Psychosis in 2 children treated for Tuberculosis: Case reports and literature review. Int J Med Pharm 2016; 6(4): 1-6.

[79] Al-Amiry MHA. Pyrazinamide induced photosensitivity: A case report from Iraq. J Pharmacovigilance 2013; 1: 103.

[80] Khan FY, Rasoul F. Rifampicin-isoniazid induced fatal fulminant hepatitis during treatment of latent tuberculosis: A case report and literature review. Indian J Crit Care Med 2010; 14(2): 97–100.

[81] Mattioni S, Zamy M, Mechai F, Raynaud JJ, Chabrol A, Aflalo V, et al. Isoniazid-induced recurrent pancreatitis. JOP J Pancreas 2012;13(3): 314-316.

[82] Ahsan MJ, Ansari MY, Yasmin S, Jadav SS, Kumar P, Garg SK, et al. Tuberculosis: Current treatment, diagnostics, and newer antitubercular agents in clinical trials. Infect Disord Drug Targets 2015; 15(1): 32-41

[83] Palomino JC, Martin A. Tuberculosis clinical trial update and the current anti-tuberculosis drug portfolio. Curr Med Chem 2013; 20(30): 3785-3796.

[84] Khusro A, Sankari D. Synthesis and estimation of total extracellular protein content in Bacillus subtilis under mild stress condition of certain antimicrobials. Asian J Pharm Clin Res 2015; 8(1): 86-90.

Document heading 10.1016/j.apjtm.2016.09.005

5 July 2016

in revised form 10 September 2016

Ameer Khusro, Research Department of Plant Biology and Biotechnology, Loyola College, Nungambakkam, Chennai – 600034, Tamil Nadu, India.

Tel:+91 8939253216

E-mail: armankhan0301@gmail.com

✉ Paul Agastian, Research Department of Plant Biology and Biotechnology, Loyola College, Nungambakkam, Chennai – 600034, Tamil Nadu, India.

Tel: +91 9444433117

E-mail: agastian@loyolacollege.edu/agastianloyolacollege@gmail.com

Foundation project: This study was supported by Maulana Azad National Fellowship (F1-17.1/ 2015-16/MANF-2015-17-BIH-60730), University Grants Commission, Delhi, India.

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine2016年11期

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine2016年11期

- Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine的其它文章

- Modifiable determinants of attitude towards dengue vaccination among healthy inhabitants of Aceh, Indonesia: Findings from a communitybased survey

- Clinical significance of dynamic detection for serum levels of MCP-1, TNF-α and IL-8 in patients with acute pancreatitis

- Expression and mechanism of action of miR-196a in epithelial ovarian cancer

- Protective effect of antioxidant on renal damage caused by Doxorubicin chemotherapy in mice with hepatic cancer

- Mechanism of action of Zhuyu Annao pill in mice with cerebral intrahemorrhage based on TLR4

- Acetylcholinesterase, butyrylcholinesterase and paraoxonase 1 activities in rats treated with cannabis, tramadol or both