Performing arts as a social technology for community health promotion in northern Ghana

Michael Frishkopf, Hasan Hamze, Mubarak Alhassan, Ibrahim Abukari Zukpeni, Sulemana Abu, David Zakus

Performing arts as a social technology for community health promotion in northern Ghana

Michael Frishkopf1, Hasan Hamze2, Mubarak Alhassan3, Ibrahim Abukari Zukpeni4, Sulemana Abu5, David Zakus6

Objective:We present first-phase results of a performing arts public health intervention,‘Singing and Dancing for Health,’ aiming to promote healthier behaviors in Ghana’s impoverished Northern Region. We hypothesize that live music and dance drama provide a powerful technology to overcome barriers such as illiteracy, lack of adequate media access, inadequate health resources,and entrenched sociocultural attitudes. Our research objective is to evaluate this claim.

Methods:In this first phase, we evaluated the effectiveness of arts interventions in improving knowledge and behaviors associated with reduced incidence of malaria and cholera, focusing on basic information and simple practices, such as proper hand washing. Working with the Youth Home Cultural Group, we codeveloped two ‘dance dramas’ delivering health messages through dialog, lyrics, and drama, using music and dance to attract spectators, focus attention, infuse emotion,and socialize impact. We also designed knowledge, attitude, and behavior surveys as measurement instruments. Using purposive sampling, we selected three contrasting test villages in the vicinity,contrasting in size and demographics. With cooperation of chiefs, elders, elected officials, and Ghana Health Service officers, we conducted a baseline survey in each village. Next, we performed the interventions, and subsequently conducted follow-up surveys. Using a more qualitative approach,we also tracked a select subgroup, conducted focus group studies, and collected testimonials. Surveys were coded and data were analyzed by Epi Info.

Results:Both quantitative and qualitative methods indicated that those who attended the dance drama performances were likelier than those who did not attend to list the causal, preventive, and transmission factors of malaria and cholera. Also, the same attendees were likelier than nonattendees to list some activities they do to prevent malaria, cholera, and other sanitation-related diseases, proving that dance dramas were highly effective both in raising awareness and in transforming behaviors.

Conclusions:As a result of this study, we suggest that where improvements in community health depend primarily on behavioral change, music and associated performing arts – dancing,singing, and drama – presented by a professional troupe offer a powerful social technology for bringing them about. This article is a status report on the results of the project so far. Future research will indicate whether local community–based groups are able to provide equal or better outcomes at lower cost, without outside support, thus providing the capacity for sustainable, localized health promotion.

Music; dance; drama; edutainment; community health; sanitation; malaria; Ghana

Introduction

Goals, hypothesis, and scope

‘Singing and Dancing for Health’ is an ongoing, arts-based public health initiative, centered on the creation, evaluation,and re finement of artistic performance – ‘dance dramas,’ combining music, dance, costume, poetry, narrative, melodrama,and comedy – as a highly economical public health technology: an intervention supporting health promotion in Dagbanispeaking rural areas of Ghana’s Northern Region.

In the first phase of this project, described in this article, our central concern was to design dance dramas to combat malaria and cholera by manipulating aesthetic elements to attract spectators and transfer key health messages, redundantly through multiple registers (cognitive, emotional, and social), relevant to knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors that might help reduce the incidence of these endemic diseases, without the physical health service technologies, such as clinics and laboratories,which typically require a much greater investment of capital.

Our hypothesis was that the impact of such interventions would prove measurably effective in raising awareness,changing attitudes, and modifying practices toward such a reduction. This impact would first affect those in attendance(and our aim was to maximize that number to the capacity of the performance space) but would subsequently diffuse –through ordinary social networks, as de fined by family and work relationships – to nonattending villagers. The fundamental method was therefore simple: develop the dance dramas(scripting, composing, choreographing); rehearse and re fine them; publicly perform, film, and subtitle them (thereby testing the method, while generating a media version for future presentation and possible broadcast); conduct preintervention surveys; perform and observe the intervention; conduct postintervention surveys; and analyze the resulting data.

We selected the rural Northern Region because it is one of the country’s poorest regions and one most lacking in health services. Because dance dramas center on language, and we did not wish to deal with the additional complications of translations and multilingual performers, we needed to select one language. We picked Dagbani, the language spoken by the Northern Region’s majority ethnic group, the Dagomba, who traditionally inhabit the kingdom of Dagbon, and the primary language of our artistic partners, the Youth Home Cultural Group (YHCG). To leave open the possibility of comparison from as many angles as possible, we selected three contrasting villages of Dagbon: Tolon (a district capital of about 4000 inhabitants), Ziong (a smaller town), and Gbungbalaga(the smallest, near Yendi, the traditional capital of Dagbon).A fourth village, Jekeriyili, lying within greater Tamale yet exhibiting features of remote rural settlements, served as a convenient yet realistic location for performing and filming each dance drama before a live audience.

Background: Northern Region, Dagomba, dance drama

Of Ghana’s 10 administrative regions (Fig. 1), the Northern Region is perhaps least served by the national system, as judged by its population and a scarcity of resources. All three northern regions (Northern Region, Upper East Region, and Upper West Region) suffer from similar problems, but the Northern Region is by far the largest of the three. For this reason it is frequently targeted in development, not only in health but also in many other areas (education, agriculture). The establishment of the University for Development Studies in 1993, with campuses in each of the three northern regions, was intended to help ameliorate this situation, but much work remains.

According to the 2010 census, the population of Ghana’s Northern Region was 2,479,461 (Ghana’s fourth most populous region) [1]. Yet only 37.2% of this population was literate, by far the lowest literacy rate across all the regions [1]. The region also exhibits the third highest percentage of rural population(69.7%), the lowest population density (35.2/km2), the lowest percentage of rural households with a computer (0.86%), the second lowest mobile phone ownership rate (5%), the lowest Internet use rate (0.32%), the third lowest household electrifi-cation rate (36%), and the second lowest rate of in-household toilet facilities (27%). Combining statistics shows that the Northern Region suffers – and by far – from the worst ratio of population to health professionals across all 10 regions [1,2]. These facts indicate the extent and severity of the Northern Region’s underdevelopment, including the dif ficulty of providing adequate health services, severity of sanitation issues, and lack of adequate media penetration. Its predominantly rural character and low population density exacerbates problems of health care access, while increasing the importance of local health knowledge and good practices. They also suggest that live performance – centered on traditional themes in oral culture, and gathering audiences in the manner of traditional performance culture – might provide an effective technique for dissemination of health information.

The Dagomba people of Ghana, speaking Dagbani and numbering more than 650,000, constitute the Northern Region’s largest ethnic group. Predominantly Muslim, the Dagbani-speaking population stretches from just west of the regional capital (Tamale) to the eastern border with Togo(near Yendi, the traditional seat of power), bulging north in the middle (i.e., from about 9° N to 10.5° N, and from about 1.5° W to 0.5° E) [3]. The land is savanna, and although hot dry weather prevails, malaria is endemic, and sanitation problems are rampant. The Dagomba also feature a lively performance culture, centered on drumming, dancing, and singing in Dagbani; community performances are held on both traditional and civic holidays, and performances as well as praise drumming are associated also with the chieftaincy.Although traditional performance has declined in rural areas because of poverty, drummers and drumming are highly esteemed and their association with political power infuses a range of performance styles inculcated from an early age[4–10].

Village dance dramas are a modern artistic form, diffused throughout Ghana, enjoyed by all its ethnic groups on various occasions, including traditional and civic holidays,and sometimes even funerals. Unlike traditional culture,centered on participatory (no audience) or formal-ritual(not entertainment) performance, dance dramas are clearly marked as light entertainment, performed by experts, for an appreciative audience. The contemporary dance drama form appears to have been in fluenced by the popular ‘Concert Party,’ with its roots in the colonial era [11], and by postin-dependence elite performance (e.g., the Ghana Dance Ensemble under director Francis Nii-Yartey) disseminated via mass media [12].

Both directions reflect a fusion of Western aesthetics and presentation styles with traditional performance genres such as storytelling, music, and dance. The dance drama offers at least two distinct advantages for public health interventions. First,it combines complementary art forms to powerfully amplify impact: the spectacular attraction of costume and dance; the social engagement of humor and melodrama; the discursive reasoning of dramatic dialog; the memorable messaging of lyrics; and the emotional impact of drumming and singing.Second, as a relatively new expressive form the dance drama genre enjoys an artistic freedom that may not be extended to those perceived as either too traditional or too foreign to be tampered with extensively.

Methods

Evidenced-based participatory action research

We applied a participatory action research (PAR) paradigm(Fig. 2) [14], forming a collaborative multinational team to set the research agenda, implement it, assess it, and analyze evidential data, both quantitative and qualitative. This team included a variety of participants: Canadian university researchers (ethnomusicology, global health, medicine),Ghanaian researchers (community health, family medicine,communication), Ghanaian writers and artists (scriptwriters,choreographers, actors, musicians, and dancers in Tamale and Accra), Ghana Health Services officers (in the three research villages), and local opinion leaders (chiefs, elders, religious leaders, teachers, and elected officials, among others) in the communities where we worked.

Of course, the broader ‘team’ included also traditional village music groups who performed before our intervention, subjects for surveys and focus groups, and the audience itself, taking an active role in watching and responding to performances. The project is ongoing, in the manner of PAR’s ongoing cycles, each phase informing the next. This article provides only a snapshot, a status report on the results of the project so far.

Our ongoing team approach distinguishes what is otherwise an ‘edutainment’ project from most other efforts of this type [15]. In the PAR process input sought from multiple parties, consensus is sought and ownership is shared. (In contrast, YHCG had composed and performed developmentoriented dance dramas for UN agencies to film, but was essentially hired for services rendered, and was not even provided with a copy of the results).

Not everyone contributed equally to the project as a whole,and modes of participation differed widely. But the team collectively shares ownership of the project; participants understand its real importance and feel – according to their participation – personally invested in it. Credit for its various aspects is assigned to those who contributed the bulk of relevant intellectual or artistic work. Thus the dance dramas are credited to artists affiliated with YHCG in Tamale, videos are credited to the videographers and editors who produced them, and academic articles and presentations are credited to those who invested time and effort in their production.Compensation went only to Ghanaians who contributed the bulk of the work as researchers or artists and for whom such work is their livelihood. We found this collaborative strategy to be not only more ethical but also more effective, generating cooperation.

Team

The core team included the following groups, individuals, and roles:

• YHCG (www.yhcg.net/), an NGO founded in 1985 by a group of local artists from Tamale provided the core performing group, augmented by two professional comic actors.

• Abdul Fatawu Karim, artistic director for the dance drama project and assistant director of the YHCG musical group, led rehearsals and developed choreographies.

• Abu Sulemana, Health Promotion Officer and Secretary of YHCG, directed the productions, coordinated operations, handled local finances, and assisted in data collection and media production.

• Mubarak Alhassan helped develop the survey instrument and oversaw its testing, implementation, coding,and archiving.

• Ibrahim Zukpeni, assisted in data collection, audiovisual (AV) documentation, coding, and archiving.

• Michael Frishkopf, Professor of Music, Director of the Canadian Centre for Ethnomusicology, and Adjunct Professor of Medicine and Dentistry at the University of Alberta, developed the initial concept and worked on all of its phases, especially fundraising, budgeting, and applied ethnomusicology.

• David Zakus, Professor of Distinction in Global Health,Ryerson University, served as global health advisor and guided the scienti fic dimensions of the project.

• Hasan Hamze, conducted statistical analyses of the survey data.

• Chiefs and Ghana Health Services officials in each village, who helped prepare communities to receive researchers and interventions, ensuring public acceptance and smooth progress.

Timeline

The project was initiated in January 2014 with face-to-face discussions, including Michael Frishkopf and principals of YHCG (who were at that time engaged in other collaborative research), to identify key health issues – malaria and sanitation (particularly, cholera) – that might be addressed. Michael Frishkopf applied for grants and succeeded in obtaining funding from the Killam Foundation, with contributions also from the Faculty of Arts and the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Alberta and Canada’s Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade, and Development.

With guidance from YHCG, we worked with an Accrabased scriptwriter to develop two scripts – centered on malaria and sanitation – which were vetted and edited by David Zakus and Michael Frishkopf for scientific accuracy and narrative flow. Revised scripts were translated into Dagbani, and – augmented with songs, choreography, and traditional musical styles – used as the framework for dance dramas designed to appeal to villagers.

Initial performances took place in Jekeriyili, a village within Tamale, providing a natural setting for a two-camera video shoot; footage was edited and subtitled for mass dissemination (available at http://bit.ly/sngdnc4h).

The team generated a list of potential research sites;although initially we hoped to perform in as many as six villages, budgetary constraints necessitated our limiting our ambition to three villages: Tolon, Ziong, and Gbungbalaga(see Fig. 1). The Ghanaian team initially visited each village twice, applying “community entry” strategies, seeking to gain the community’s cooperation by explaining the project and its benefits, first to opinion leaders – chiefs, elders, religious leaders, teachers, elected officials, and Ghana Health Service officers – and conducting protocols as demanded by tradition.We also photographed the village and its inhabitants and possible sites for the performance. These strategies also served to publicize the coming project. Further publicity arose through extensive placement of posters (Fig. 3) in each village location.

Meanwhile we developed a survey instrument in Canada,which was re fined and tested by the Ghanaian team, resulting in a printed-paper survey to be administered through oral interview (Fig. 4). With the support of the community we then conducted preintervention survey research (November 2014),performed the interventions accompanied by participantobservation research (December 2014), and conducted postintervention research, including follow-up surveys, focus group discussions, testimonials, and tracking. Surveys were scanned and coded by Epi Info. Finally, we produced descriptive statistics and conducted a rigorous correlative analysis. These project phases are described further in the following sections.Preintervention research:Preintervention research centered on a16-page knowledge–attitude–practices (KAP) survey comprising several sections of questions: demographic pro file;knowledge about each disease (cause, symptoms, transmission, prevention, treatment); attitudes to the disease, those it afflicts, and obstacles to prevention or cure; and related practices that either prevent or exacerbate the condition. We also asked about access to media, sources of health information,perceived efficacy of dance dramas for public health, favorite musical artists and styles, and musical listening practices.

About 45 min was required for administration of the survey. The research team administered 80 surveys in each of the three villages. As extracting a scientifically determined random sample proved difficult, we did so informally, by selecting respondents at random from a variety of locations, including markets, community centers, and schools, at different times of day. Each village necessitated 3 days of surveying.Intervention research:The intervention itself required an entire day in each village. Arriving from Tamale in the morning via van (for artists), truck (for equipment), and car (for others), we formally greeted chiefs, elders, Ghana Health Service officials, elected officials, and other dignitaries. Posters were placed everywhere, and a large banner was unfurled to mark the primary performance site (Fig. 5).

We set up a wooden stage and a sound system, as well as documentary video and audio recording devices, including a professional tripod-mounted camera focused primarily on the stage (stationary, except occasionally panning left and right, and zooming in and out), and a second, head-mounted GoPro camera to circulate around the performance space, capturing video of audience members. Team members not participating in the dance drama took still photographs. A professional audio recorder supplied ambient audio recordings to supplement the more focused audio captured by the video camera’s directional microphone.

Use of a raised, portable wooden stage (custom-built for this project) together with a wireless microphone PA system enabled a much larger village audience to benefit from the onstage live dance drama and served as a kind of compromise between mediated forms (with tremendous reach, but only in areas where media reception is available, and lacking the power of live performance interaction) and traditional live forms(which are limited by the angle of view and the scope of sound).Actors, singers, and speakers sharing wireless microphones and standing on the stage were widely visible and audible.

A DJ playing recorded music – especially local varieties of hiplife, popular throughout Ghana – through the PA system served to informally announce the event’s onset.This attracted a crowd of onlookers, especially children and youths, who would begin to dance. A group of performers from YHCG performed a procession starting from the performance grounds, circling through the village, and returning.Incorporating drumming, dancing, and comic actors dressed as clowns, the procession gathered many onlookers in its wake, streaming before and behind and ultimately joining the growing audience (Fig. 6).

Once a sizable crowd had assembled, a local drum and dance group, organized by the local chief and elders, informally opened the performance segment (e.g., a simpa group performed in Tolon). Through such active community involvement, we not only grew our audience but also blurred the lines between ‘performers’ and the ‘audience,’ encouraging the village community to assume some ownership of the event.

Formal proceedings followed with a benediction from religious leaders and short speeches from chiefs, elders, Ghana Health Service officials, and Michael Frishkopf, locally recognized as both a researcher and a subchief (‘Maligu Naa,’meaning ‘chief of development’) in Tolon (and dressed accordingly). These speeches, including statements of goodwill, were followed by performances of the two dance dramas, back to back, attracting a crowd of around 750 people in each of the three villages. Initially we had wanted to also include some dance and music workshops for the young people but we found that the two performances required at least 3 h to complete them and – if not timed carefully – were sometimes interrupted by prayers. Some further remarks of thanks closed each day’s events, and the stage and equipment were dismantled and packed for the return to Tamale.

Postintervention research:In the 2 weeks after the interventions, we conducted focus group discussions with the youth of each village (Fig. 7), recording their reactions and finding out what they had learned and what sorts of improvements they could suggest for the intervention.

Follow-up surveys were administered in phases. Originally we intended to administer a group of surveys every few weeks,with the intention of thereby understanding the process by which knowledge, attitudes, and practices changed over time.However, budgets and logistical factors precluded such rigor,and we finally managed to administer the follow-up survey in two phases only: the first following the intervention by about 1 month, and the second after 2 months, for a total of 60 followup surveys per village, requiring another 3 days of surveying in each phase. These were combined in the analysis because each sample was too small to warrant independent statistical analysis.

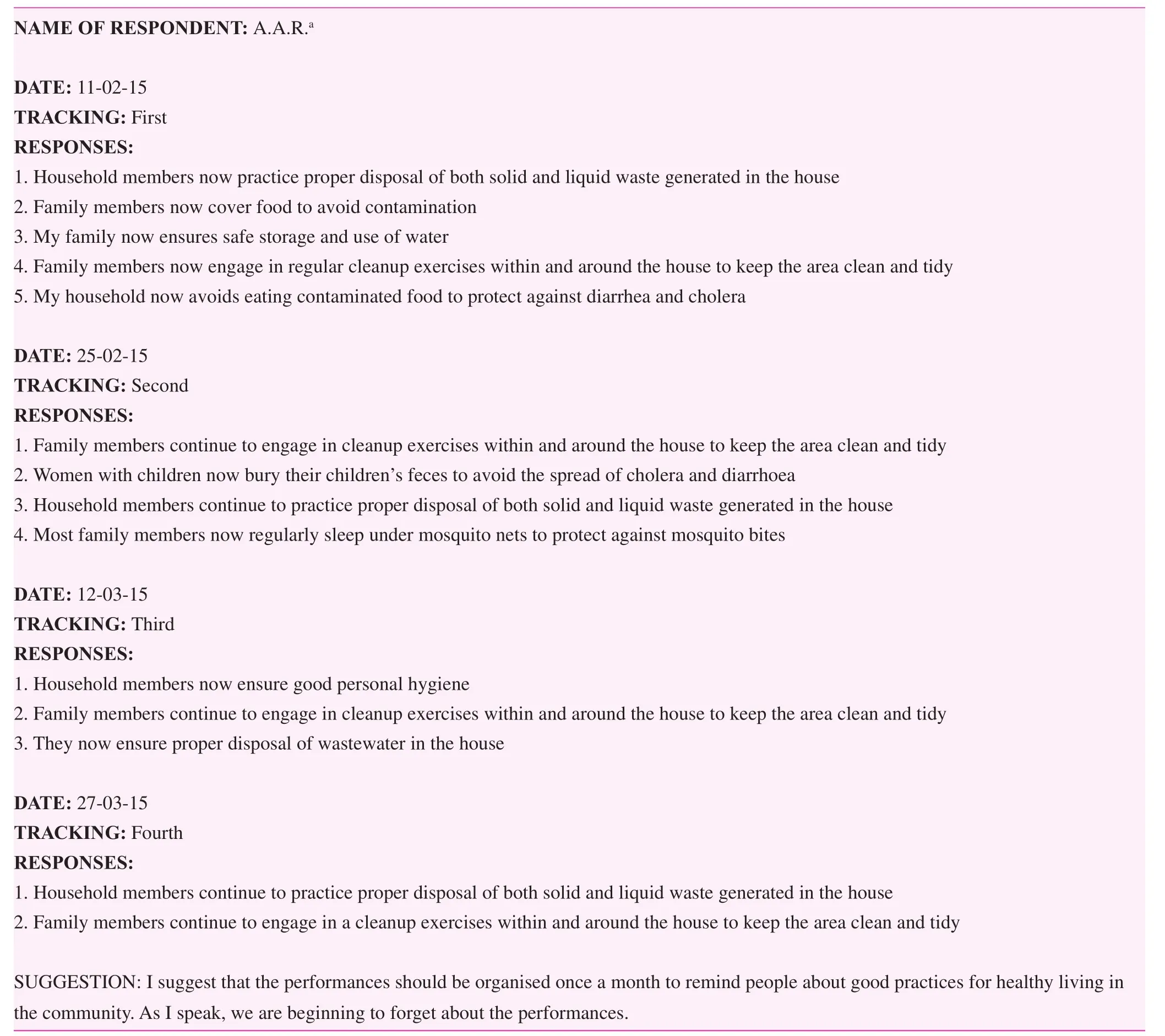

We also selected a small number of individuals, articulate and observant, in each village for ‘tracking.’ We took their phone numbers and contacted them four times each, at 2-week intervals, to find out what sorts of behavioral changes they had observed in their villages. Such follow-up from the perspective of a fixed, ‘embedded’ observer and taking advantage of cell phone technology for rapid collection of data proved to be very useful.

Quantitative data analysis:Quantitative data emerged from KAP surveys administered both before and after the interventions. Rather than selecting a single random sample to be surveyed both before and after the intervention, we surveyed two independent random samples in each of the three villages,one before and one after the intervention, for both theoretical and practical reasons. Our theoretical motivation was based on a desire to understand the overall impact of the intervention,which could potentially include not only the direct impact on attendees but also its indirect impact through knowledge diffusion. This overall impact would not have been revealed by our surveying the same subjects before and after the intervention,because, having been selected and surveyed the first time, this sample might no longer represent the village as a whole afterward (e.g., the very act of surveying might have predisposed them to attend – or at least to shift responses). Comparing only survey results provided by the sample subset that actually attended the intervention would have been only marginally interesting, because it would have been rather surprising if there were not an impact on this subset. More practically, it would have been extremely challenging to survey the same people twice, even if they were willing. (However, we did conduct a tracking study, producing more qualitative results as described later).

Obviously all preintervention surveys centered on knowledge, attitudes, and practices of those who had not been impacted by the intervention, because it had not yet transpired. However, the postintervention surveys can be divided into two groups: surveys of those who attended (POST-A) and surveys of those who did not attend (POST-N); both groups received potential impact from the intervention, whether directly via experience (POST-A) or indirectly via diffusion(POST-N).

In seeking to understand intervention impact, we sought a comparison evincing maximal impact; if such impact could not be demonstrated, then the intervention’s impact as a whole could be deemed negligible. Given that we were dealing with two independent samples, we had several choices: we could have compared all preintervention and all postintervention surveys but this contrast would have been muted by the inclusion in the latter of POST-N surveys generated by subjects who did not receive any impact, and whose surveys would thus resemble preintervention surveys to a great extent, thereby muting the comparison; we could have compared POST-A and POST-N surveys but in this case the contrast would have been muted by the inclusion of POST-N surveys generated by subjects who nevertheless did receive impact, and whose surveys would thus resemble POST-A surveys to some extent.In search of data revealing the strongest possible contrast, we thus elected to eliminate consideration of the diffusion factor in this initial research phase and compared preintervention and POST-A surveys. The study of POST-N surveys and the impact of diffusion is deferred to subsequent analysis. KAP variables were controlled for variations in age, sex, education,and geographic location.

Results

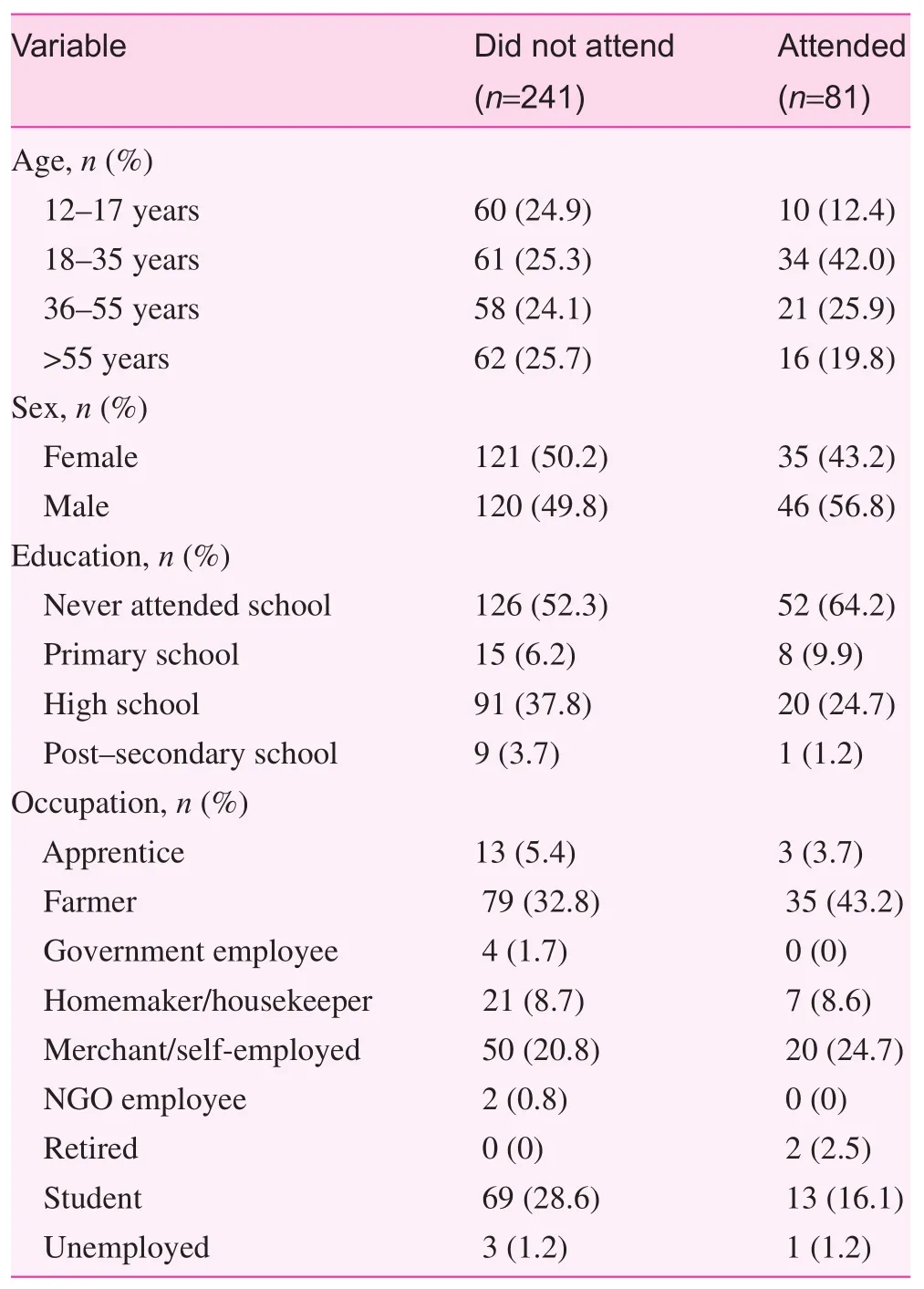

Demographic data

Demographic variables comparing the preintervention and POST-A groups are outlined in Table 1. The preintervention group consisted of a relatively equal number of subjects from the four age groups (12–17 years, 18–35 years, 36–55 years,and older than 55 years), compared with the POST-A group,which consisted of a majority of 18–55-year-old subjects. The preintervention and POST-A groups consisted of 50.2% and 43.2% females, respectively. Large majorities of subjects in both groups had never attended school and were either farmers or merchants.

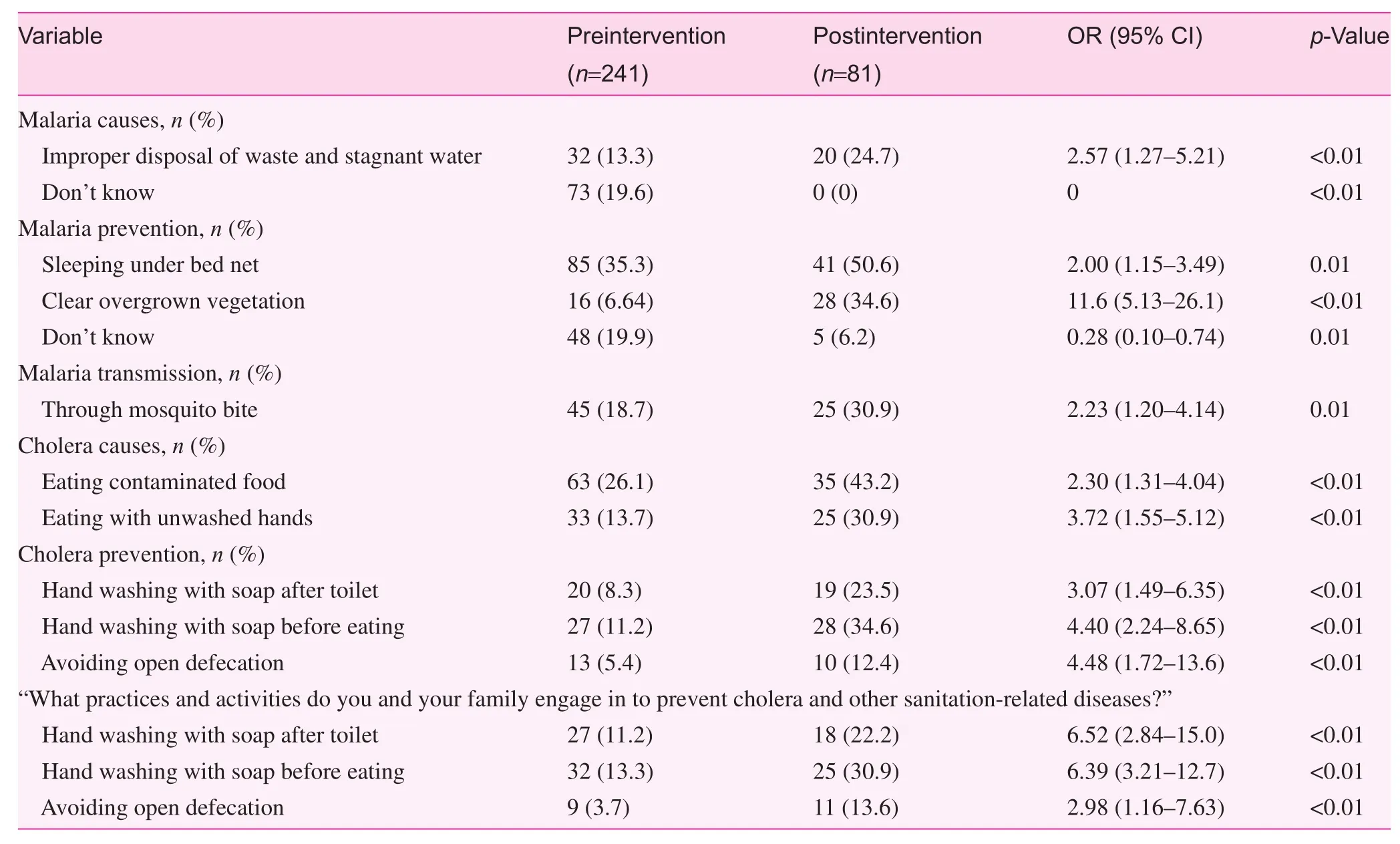

KAP survey data

An analysis of the KAP surveys comparing the preintervention and POST-A groups revealed a signi ficant impactin several respects, as summarized by Table 2. Those who attended the song and dance dramas had 2.57 times the odds to list “improper disposal of waste and stagnant water” as a cause of malaria (p≤0.01), 2.00 times the odds to list “sleeping under bed net” (p=0.01) and 11.6 times the odds to list“clearing overgrown vegetation” (p≤0.01) as malaria prevention methods, and 2.23 times the odds to list “mosquito bite”as a method for malaria transmission (p=0.01) compared with those who did not attend the song and dance dramas. Likewise,knowledge of cholera causes and prevention increased signifi-cantly. Those who attended the song and dance dramas had 2.30 times the odds to list “eating contaminated food” and 3.72 times the odds to list “eating with unwashed hands” as causes of cholera (p≤0.01), 4.40 times the odds to list “hand washing with soap before eating,” 3.07 times the odds to list”hand washing with soap after using toilet,” and 4.48 times the odds to list “avoiding open defecation” as methods of cholera prevention (p≤0.01) compared with those who did not attend the song and dance dramas. The KAP surveys also revealed a few preventative activities that those in the POST-A group were likelier to engage in compared with those in the preintervention group. Those who attended the song and dance dramas had 6.52 times the odds to list “hand wash with soap after toilet,” 6.39 times the odds to list “hand washing with soap before eating,” and 2.98 times the odds to list “avoiding open defecation” as practices that they and their family engage in to prevent cholera and other sanitation-related diseases.

Table 1. Demographic variables

Qualitative data

The project produced three types of qualitative data – focus group feedback, tracking data, and testimonials – con firming the quantitative results, serving as a ‘sanity check’ against purely numerical interpretation and enriching the project with case studies and feedback.

Focus group feedback:During the 2 weeks after the performance, we conducted one sex-balanced focus group session at each village site to elicit comments from the youth, who represent the future of each community, and appeared the likeliest to have the time and energy necessary to participate. Each group comprised 20 junior high school students. In the midst of their formal education, and as yet relatively unjaded by life’sharsh realities, we hoped that they would be both articulate and forthright in their responses. We were also interested in targeting the same demographic for participation in youth ‘Singing and Dancing for Health’ groups planned for the sustainability phase of the project (see later). The focus groups were led by two experienced facilitators, Mubarak Alhassan and Ibrahim Abukari Zukpeni.

Table 2. Analysis comparing 241 preintervention surveys with 81 postintervention surveys of those who attended the intervention

We sought and received participants’ consent before conducting these sessions. Participants agreed to participate, as well as to be recorded during discussions. Participants were then provided with nametags and gathered into a circle in a school classroom; activities began with prayers (standard for local group activities), followed by a series of games, dancing, and singing, to help everyone feel more comfortable and ensure a more interactive discussion. Refreshments were also provided at a break. Proceedings were recorded and transcribed into Dagbani, with summaries in English.

Two primary group of questions guided the proceedings:(1) What do you think are the most critical health issues facing your village? What are the obstacles to better health? How could they be addressed through changes in knowledge, attitudes, and practices? (2) What did you like and dislike about the productions? How could the performance be improved?

Some of the answers from the Tolon group included the following:

1. Participants mentioned malaria, fever, cholera, ulcer,diabetes, and severe headache as the severest and most prevalent diseases plaguing their communities. They viewed the widespread practice of open defecation as the root cause of cholera and other diseases. Education was held to be the best way to address health issues, because,as one participant noted, “when you are educated, you get to know the causes and consequences of diseases through some school curricula activities.” They recommended other changes in practice, such as encouraging communal work in the village as a means of ensuring sanitation, and washing their hands with soap after visiting the toilet.

2. Generally, they enjoyed the production, viewing it as enhancing and strengthening traditional culture as well as encouraging good practices for improved health, particularly by sharing knowledge related to good hygiene and sanitation. They enjoyed the health-related songs,and the dramatic aspects of the production. They also offered constructive feedback, criticizing some of the dancing as haphazard, and expressing discomfort about dramatizing death or disobeying the chief. Generally,they appreciated the inclusion of comedic routines and encouraged us to include more Dagbani comedians. They suggested additional scenes illustrating consequences of not covering food, improper disposal of wastewater,improper defecation, not using mosquito nets, and eating without washing hands first.

Tracking data:After the interventions we enlisted 30 articulate, observant volunteers – 10 from each village – to share their telephone numbers with the core research team so they could be contacted approximately every 2 weeks to report on observed behavioral changes in their homes. Each volunteer provided four short reports. The fundamental question was:“What is your perception of the attitudes and practices of family members in the same household after the intervention?” We also sought suggestions. An example is provided below.

Testimonials:After the intervention we conducted interviews with several participants, particularly community leaders, in search of testimonials we might use to promote the project, especially in the pursuit of further funding. Although of limited statistical validity, the following quotations do far more than promote the project; by providing personal perspectives they offer a humanistic response that is entirely missing from the Tables 1 and 2, and which can serve also to redirect the project in ever more productive directions.

I.M. (chief): “I was happy about the performance, because all that was said was geared towards healthy living and to ensure that we are healthy all the time. We learnt a lot from the performance, especially keeping our surrounding[s]clean, sleeping under mosquito [nets] and washing of our hands with soap. This will help us fight against malaria and cholera. However, I am appealing to you that if you could provide us with toilet facilities to help us reduce the practice of open defecation, which is a major cause of cholera in the community.”

M.I. (chief): “I want to thank your team for the fantastic work you did. Indeed, the performance went well because I learnt many lessons from the dance drama. We were reminded to sleep under mosquito nets, wash our hands with soap after toilet and cleaning of our surroundings. I cannot express how much we were entertained watching your artists performed[sic]. It was entertaining, educative, all in one production.I can’t wait for more performances in this community and beyond.”

A.N. (indigene of Tolon): “In fact, the whole performance was great, especially the Malaria and Cholera songs. It reminded us of the Dagbon tradition and triggered us to change our attitudes towards healthy living. After the performance, I have seen some attitudinal changes in my household because members of my household who attended the performance now engage in a lot of cleanup exercises and washing of hands with soap before eating and after toilet”.

A.M. (indigene of Tolon): “Oh my God!! The performance was one of the best I have ever witnessed. In fact,I had so much fun and education on malaria and cholera prevention. Thank you so much for given [sic] our community such an opportunity to live a healthy life, free of diseases. You have taught us how to guard or fight against malaria and cholera. Thank you for this positive move in our community.”

A.A.T. (Gbungbalaga opinion leader): “I was very happy about the performance and did not even know what to say, but I pray that it should continue so that we can bene fit from it.If these performances continue, it will help change our attitudes towards our health. Indeed, we bene fitted from the performances because it triggered us to be healthy and if you are healthy, you will be able to work to feed your family. Therefore,poverty will be a thing of the past if we are all healthy and strong and can work to feed our families.”

Tracking data example

S.A. (indigene of Gbungbalaga): “The drama was fantastic and the traditional dances performed were great. During the performance, I was reminded of some good health practices such as keeping of the surrounding[s] clean, sleeping under mosquito net and washing of hands with soap to prevent against malaria and cholera. We are looking forward to more performances.”

Discussion

Both quantitative and qualitative data indicated that dance drama interventions produce signi ficant changes in knowledge, attitude, and behavior, and constitute an effective social technology for progress in public health, especially in regions of high illiteracy and poverty rates, where more conventional,material health service technologies are too expensive to implement. Dance dramas provide several advantages. Not only do they sensitize attendees to health issues and convey concrete health information, they also do so in an atmosphere charged with emotion and social solidarity, and thus tend to form bonded collectivities with health concern at their core.Although some social health progress must necessarily depend on more expensive, material interventions, it seems clear that where progress in global health depends primarily on behavioral change, music and drama present a powerful means for building sustainable capacity to achieve it. PAR techniques,working hand in hand with communities, offer a powerful strategy for including local input, as our focus groups clearly demonstrated, by proposing many ideas for future productions,and helping guide future cycles of PAR research.

What is missing is a means of ensuring sustainability;although the project proved the efficacy of the dance drama method to raise awareness and knowledge, improve attitudes,and change behaviors, time and consequent forgetfulness can reverse such gains. Qualitative feedback also indicated the desire to provide regular ‘Singing and Dancing for Health’ performances, and yet doing so is impossible – even in just these three villages – without significant injections of outside support because of the high costs of performance. TV and Internet broadcasts might fill the gap in cities but are not an effective solution in villages lacking access to these media. Several new directions are being explored which would require far lower,if not zero, cost.

Two have been proposed but not yet tried:

1. Radio drama broadcasts. Radio is widely received in rural areas of the Northern Region; studies have shown that radio is especially effective in reaching women[16–20]. Dance dramas would first have to be reformulated as radio dramas, by removal of the visual element,perhaps with complementary emphasis on music.

2. Village movie house performances. Many Dagomba villages contain movie houses where videos are screened,played back on DVD or Video CD players, to local audiences. We could distribute our dance dramas on DVD or Video CD to movie houses across the region. In this case there may be a bias toward men; further research is required to ascertain to what extent women also attend movie houses.

The third strategy, local ‘Singing and Dancing for Health’groups, appears most promising, and is furthest along thanks to two small grants: we intend to establish local youth groups,equipped and trained by YHCG, and overseen by parents and teachers, to perform a health-oriented repertoire on school,civic, traditional, and religious occasions, as well as to herald programs or speeches from Ghana Health Service of ficers.Such groups can achieve several congruent goals: they gather multiple generations and revive traditional performance types,thus strengthening the social fabric; they serve as effective community mobilization devices; and they have the potential to incorporate health-oriented dance dramas, and their component songs and dances, into the local oral tradition, to be passed down through the generations. Once these performance and social types have been incorporated into local oral tradition, we believe we have a plan for sustainable singing and dancing for health. With funding from the University of Alberta, a new Tolon youth group was inaugurated in July 2015; formation of a similar group in Ziong is under way.Future research will reveal to what extent this sustainability plan may succeed.

Con flict of interest

The authors declare no con flict of interest.

The results reported in this article have not been in fluenced by any relationships, circumstances, or activities that might pose, or even be perceived as posing, a con flict of interest.

Funding

This project was enabled by a Killam Cornerstone Grant,together with additional contributions from the Faculty of Arts, the Of fice of Global Health in the Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry, and the Centre for Health and Culture at the University of Alberta, as well as a subgrant from the Canadian Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade, and Development.The support of these institutions and agencies is gratefully acknowledged.

1. Ghana, Statistical Service. 2010 population & housing census:summary report of final results. 2012.

2. Ghana Health Service. The health sector in Ghana: facts and figures. Accra: Ghana Health Service; 2010.

3. Johnson DP. Dagomba. In: Encyclopedia of Africa. Oxford:Oxford University Press; 2010.

4. Kinney S. Drummers in Dagbon: the role of the drummer in the Damba festival. Ethnomusicology 1970;14:258–65.

5. Locke D. Drum Damba: talking drum lessons. Crown Point, Ind.USA: White Cliffs Media; 1990.

6. Chernoff JM. Music-making children of Africa: a Dagomba child learns social habits and personal discipline through music.Natural History 1979;88(9):68.

7. Films for the Humanities & Sciences (Firm) FMG, Digital Classics (Firm). The Drums of Dagbon [Internet]. New York, NY:Films Media Group; 2005. http://digital. films.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?aid=8751&xtid=10510.

8. Oppong C. Growing up in Dagbon. Tema, Ghana: Ghana Publishing Corporation; 1973.

9. Staniland M. The lions of Dagbon: political change in Northern Ghana. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1975.

10. MacGaffey W. Chiefs, priests, and praise-singers: history,politics, and land ownership in Northern Ghana. University of Virginia Press; 2013. p. 213.

11. Cole CM. Ghana’s concert party theatre [Internet]. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press; 2001. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&scope=site&db=nlebk&db=nlabk&AN=66681.

12. Schramm K. The politics of dance: changing representations of the nation in Ghana. Afrika Spectrum 2000;35(3):339–58.

13. Kemmis S, McTaggart R. Participatory Action research:communicative action and the public sphere. In: Denzin NK,Lincoln YS, editors. The SAGE handbook of qualitative research.Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2005. pp. 559–603.

14. Fals-Borda O. Participatory action research. In: Cooke B, Cox JW, editors. Fundamentals of action research volume II, Varieties and workplace applications of action research. London: SAGE;2005. pp. 3–9.

15. Creativity, Arts and “Edutainment” Based Approaches | United Nations Educational, Scienti fic and Cultural Organization[Internet]. www.unesco.org/new/en/natural-sciences/priorityareas/sids/health/creativity-arts-and-edutainment-basedapproaches/.

16. Somolu O. Radio for women’s development: examining the relationship between access and impact. Nokoko 2013;3:97–107.

17. Al-hassan S, Andani A, Abdul-Malik A. The Role of community radio in livelihood improvement: the case of Simli Radio. Field Actions Science Reports The journal of field actions [Internet].https://factsreports.revues.org/869.

18. Asemah ES, Anum V, Edegoh LO. Radio as a tool for rural development in Nigeria: prospects and challenges. AFRREV IJAH: An International Journal of Arts and Humanities 2014;2(1):17–35.

19. Tucker E. Community radio in political theory and development practice. Journal of Development and Communication Studies 2013;2(2/3):392–420.

20. Kwapong O. Exploring innovative approaches for using ICT for rural women’s adult education in Ghana [Internet]. Faculty of Integrated Development Studies, University for Development Studies; 2006. www.ajol.info/index.php/gjds/article/view/35026.

1. Faculty of Arts and Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry,University of Alberta, 382 FAB,Edmonton AB T6H 3S9, Canada

2. 9851 Waller Court, Richmond BC V7E5S9 Canada

3. Grooming Dot Org, P.O. Box TL 1324, Postal Code 00233, House No. CH. EXT 14, Bolga Road,Agric Area, Tamale, Northern Region, Ghana, West Africa

4. Grooming Dot Org, P.O. Box TL 1817, Post Code: 00233,Tamale, Northern Region,Ghana, West Africa

5. Tamale Youth Home Cultural Group, P O Box 601, Tamale N/R, A Ext. 32 Hiltop, Ghana,West Africa

6. Faculty of Community Studies, School of Occupational and Public Health, Ryerson University, Room POD249, 350 Victoria Street, Toronto, ON M5B 2K3, Canada

Michael Frishkopf, PhD

Faculty of Arts and Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry,University of Alberta, 382 FAB,Edmonton AB T6H 3S9, Canada E-mail: michaelf@ualberta.ca

6 January 2016;

Accepted 22 January 2016

Family Medicine and Community Health2016年1期

Family Medicine and Community Health2016年1期

- Family Medicine and Community Health的其它文章

- Editor-in-Chief & Guest Editor

- Unregulated health care workers in the care of aging populations:Similarities and differences between Brazil and Canada

- Integration of community health workers into health systems in developing countries: Opportunities and challenges