Solar Power Highlights China’s Manufacturing Future

By JOHN ROSS

Solar Power Highlights China’s Manufacturing Future

By JOHN ROSS

John Ross is a senior research fellow at Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies, Renmin University of China. From 2000 to 2008 he was director of economic and business policy in the administration of Mayor of London Ken Livingstone. He previously served as adviser to several major international mining, finance and equipment manufacturing companies.

CHINA’s achievements in economic development and poverty reduction are historically unprecedented. But, it must never be forgotten from what an extremely low base China began its development in 1949 after a century of foreign invasions and wars.

In 1950 only 10 countries for which there is data had lower per capita GDPs than China. That by 2015 China had already achieved “upper middle income” status by World Bank standards, with a higher per capita GDP than countries containing the majority of the world’s population, therefore, denotes extraordinary progress. China has since steadily narrowed the gap between it and the world’s most advanced economy, the U.S.

Nevertheless, by 2015 China’s per capita GDP was still only 14 percent of the U.S.’s at current exchange rates and,more significantly for long-term trends, only 25 percent at purchasing power parities (PPPs). This gap in per capita GDP means China’s overall productivity level is approximately one sixth that of the U.S. at current exchange rates and one quarter at PPPs. China’s decisive economic task,over several decades, therefore, is to increase its productivity and reach the per capita GDP levels of the most advanced economies.

Productivity in Advanced Economies

This necessity to close the productivity gap with advanced economies decisively affects China’s most crucial economic sectors. A key feature of even the most advanced economies is that manufacturing productivity rises more rapidly than non-manufacturing productivity. In practice this means manufacturing productivity increases more rapidly than services productivity, as the two sectors together make up the overwhelming majority of a modern economy.

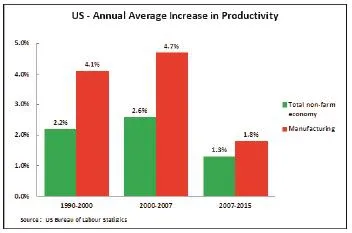

Looking at the U.S., the world’s most advanced economy, Figure 1 shows that during the entire period since 1990, often thought of as the height of the “Internet revolution,” the increase in U.S. manufacturing productivity was far higher than that of non-manufacturing. As the U.S. total non-farm economy includes manufacturing, a higher than average productivity growth sector, average productivity growth in U.S. non-manufacturing is even lower than for the whole non-farm economy. Therefore, even during the period of slow growth since the international financial crisis after 2007, the growth rate of U.S. manufacturing productivity was almost half as fast as that of non-manufacturing, while during the period of more rapid economic expansion from 1990 to 2007 U.S. productivity growth in manufacturing was almost twice as fast as that of non-manufacturing.

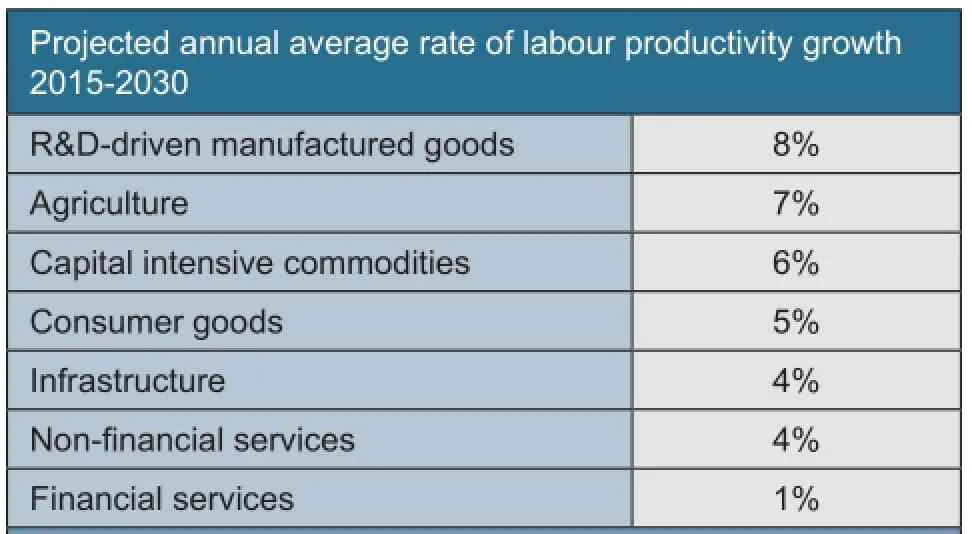

That productivity growth is much more rapid in manufacturing than services, under conditions where China’s decisive economic objective is to close the productivity gap with the most advanced economies, means that in overall terms manufacturing is China’s decisive sector. The McKinsey Global Institute, for example, drawing on international experience calculates the long-term potential for China’s economic sectors, as shown in Table 1. The highest potential for China’s annual productivity growth outside agriculture is eight percent in R&D-driven manufactured goods, six percent in capital intensive commodities, and five percent in consumer goods. This compares to only four percent in non-financial services and one percent in financial services.

Energy Supply

Within this overall framework China has several key R&D-driven manufacturing sectors. But renewable energy supply is crucial due to the struggle against climate change and the combination of domestic and international economic factors.

Figure 1

Domestically, China’s electrical energy supply still lags considerably behind the most advanced economies. China’s per capita electrical power supply is only 31 percent of U.S. levels - compared to Germany’s 56 percent, Japan’s 62 percent and South Korea’s 76 percent. As energy supply is required for the economy’s entire functioning, China cannot move towards advanced economy levels of productivity without a huge increase in power supply.

But although China’s per capita electricity power supply is below that of advanced economies it is already the world’s biggest in total terms - over 30 percent larger than the U.S. However to reach U.S. levels of per capita power supply China would have to triple its output. China,therefore, faces decades of adding to its power supply in a domestic market which dwarfs all others.

But, as China’s policy makers know, the present structure of China’s power supply is highly undesirable from the environmental viewpoint. In 2013, the latest internationally comparable World Bank data, 75 percent of China’s electrical power was coal generated compared to Germany’s 47 percent, the U.S.’s 40 percent and Japan’s 32 percent. Even with modern, and expensive, methods of handling coal burning, China’s enormous dependence on coal for power supply is highly detrimental, environmentally.

Regarding alternative energy sources, China has an advantage in hydroelectric power supply - which accounts for 17 percent of China’s electrical power compared to Germany’s four percent, the U.S.’s six percent and Japan’s eight percent. But the proportion of China’s electricity supply generated by other renewable sources lags behind other major economies. In 2012, according to the latest internationally comparable World Bank data, China produced only 2.7 percent of its electricity supply from nonhydroelectric renewable sources compared to Japan’s 4.6 percent, the U.S.’s 5.5 percent, and Germany’s 19.5 percent. This is despite China being by far the world’s largest solar panel manufacturer.

Table 1

Solar Panels

The key global trend in this field is that renewable energy supply, particularly solar power, is expanding rapidly as its price falls. In June 2016 Bloomberg Technology noted estimates of the International Renewable Energy Agency:“The average cost of electricity from a photovoltaic system is forecast to plunge as much as 59 percent by 2025.”Therefore: “The amount of electricity generated using solar panels stands to expand as much as six-fold by 2030 as the cost of production falls below competing natural gas and coal-fired plants… Solar plants using photovoltaic technology could account for eight percent to 13 percent of global electricity produced in 2030, compared with 1.2 percent at the end of last year.” Bloomberg New Energy Finance calculations were essentially the same, forecasting “growth in solar photovoltaics reaching 15 percent of total electricity output by 2040.”

China became the world’s largest producer of solar panels in 2009. Liang Zhipeng, deputy director of the National Energy Administration’s renewable energy division, estimated that in 2015 China accounted for 70 percent of the global output of solar panels - 43 gigawatts.

As solar power is undergoing rapid technological innovation, with major improvements in power-to-price ratio,R&D capacity is decisive. Alongside China’s scale of production its academic based R&D in the renewable energy field is already world leading. KIC InnoEnergy, established by the European Institute of Innovation and Technology to initiate new ways to achieve European innovation, concluded that the Chinese Academy of Sciences was the world number one academic research center in sustainable energy: “Chinese research institutions are considerably ahead of their European and U.S. peers in sustainable energy innovation, including wind, ocean and solar power as well as smart grids and intelligent buildings.” It found that nine of the world’s top 15 academic research institutions in the field were in China.

There was still weakness in transferring academic research to companies, but Diego Pavia, head of KIC InnoEnergy, noted: “Chinese researchers have told us: ‘we have learned as much as we can from Europe, and now we have to lead and create innovation...’ But they have decided to do it, so I have no doubt that they will.”

The scale of China’s solar power market gives it a decisive advantage in the sector. Between 2011 and 2015 China’s installed solar capacity increased almost 13-fold. In 2015 China accounted for more than a quarter of global solar installations. China, with the total solar capacity of 43.2 gigawatts, overtook Germany at the end of the year as the country with the most installed solar capacity.

China will rapidly expand this market, with plans to more than triple its solar power capacity by 2020, adding 15 to 20 gigawatts of photovoltaic power annually in the next five years.

Development of renewable energy, to which solar power is crucial, is decisive in the fight against climate change. But also economically because, with a rapidly expanding global market, the world’s largest home market, unequalled scale of production, and established research capacity, solar power is precisely the type of R&D based manufacturing industry that is vital for China’s future.