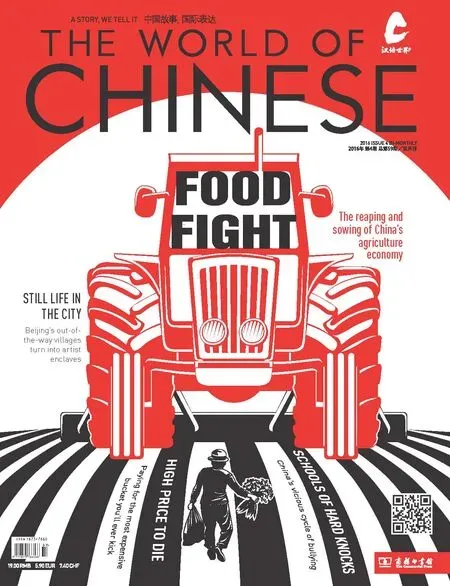

FOOD FIGHT

封面故事 COVER STORY

FOOD FIGHT

Decoding the contradictions of China's agriculture industry

俗话说“民以食为天”,农业一直是中国人心中“天大的事”

PEOPlE DON'T OFTEN INTERROGATE THEIR FOOD. CARROTS AREN'T ASKED IF THEY WERE GROWN NEXT TO A FACTORY,POTATOES ARE RARElY QUESTIONED ABOUT WHETHER THEY WERE PUllED BY A MACHINE OR AN UNDERPAID HAND, AND EXACTlY HOW CHINESE IS THAT CHINESE CABBAGE, ANYWAY? CHINA HAS MORE MOUTHS TO FEED THAN ANY OTHER NATION BUT INCREASINGlY, IT NEEDS OVERSEAS FARMS AND SUPPlIERS, AND THE FARMING CONDITIONS WITHIN THE COUNTRY ITSElF ARE STIll FAR FROM EFFICIENT. BETWEEN THE FOOD SAFETY SCARES AND THE lEGIONS OF FARMERS lACKING TECHNOlOGICAl AID THE COUNTRY STIll HAS A lONG WAY TO GO IN DEVElOPING ITS FARMING SECTOR.

PlOWING THE PATCHWORK

Even as China has emerged as the largest food producing nation on earth, its agriculture sector continues to be one of the most ineffcient. More than 34 percent of all emp loyment in China was in agriculture in 2011, according the World Bank, so one might imagine that keeping China's farms as up-to-date as possible would be a priority. But time, pollution, and econom ic development have not been kind to China's felds.

The problem here is technology, or the lack thereof.

As early as the 1960s, the concept of mechanization was important to the Chinese leadership and was regarded as an effective way for China to feed itself. But even today, when talking about agriculture, most farmers still envision a typical farm as being a small plot, w ith m inimal investment in machinery and advanced technology.

The process of mechanization has been a long and arduous one. When the Communist Party came to power, they began seizing land from landowners and distributing it among the poor. Farmers classifed as “poor peasants” were given ownership of land. But in that model, estates and large farms were divided and peasants just got small parcels. By the late 1950s, private land ownership was elim inated, and farmers were organized into teams and then collectives and became members of “people's communes” (人民公社). Initially, the Communists were trying to follow the Soviet model but then became impatient with the pace and turned to radical mass movements like the Great Leap Forward, an economic and social campaign from 1958 to 1961, which aimed to rapid ly transform the country from an agrarian economy into a socialist society through rapid industrialization and collectivization. Fam ine followed.

Then, three years after M ao's death, Deng Xiaoping attempted to decollectivize the agricultural sector, including introducing the contract responsibility system in the 1980s. Under this system, farm ing families signed contracts w ith the village or town to cultivate a given crop on a particular piece of land, after the harvest a certain amount of the crop had to be sold to the unit at a predeterm ined price, but beyond that, farmers were allowed to determine for themselves what and how to produce.

Though the system liberated productive forces to some extent, China's agricultural sector remains highly labor-intensive and history has left farmers with land fragmentation, which has become a key obstacle for China's agricultural development. Zhu Daolin, a professor from Department of Land Resources Management at China Agricultural University, says that under the system established in the 1980s, agriculture was based on fam ily as a production and management unit. It helped solve the problem of ownership and distribution and improved productivity, but at the same time led to fragmented farm ing.

Because all the farmers wanted the right to use high-quality land, lands had to be classifed into different grades and distributed equally. So, to ensure fairness, farmers all gained land of various grades in patchwork locations. This,obviously, often made the land unsuitable for using machinery.

But to be fair, fragmentation has positive side. Zhu points out that since China has a vast territory and varying topographical conditions in different areas, agricultural production needs to suit local conditions. About 34 percent of China is covered by pastures and 14 percent by forests. Only 15 percent of the country is good for actual agriculture and most of this land is on the central eastern coast and along around the Yangtze and Yellow river valleys. So in certain regions like mountainous and hilly areas, land fragmentationis a practical choice, proper for the current labor-intensive model.

Despite that, since land fragmentation increases the cost of management and obstructs large-scale farm ing and mechanization, land consolidation is inevitable, and the mechanism for this consolidation is “land transfer”.

Land transfer means transferring the rights to use the land (rather than ownership) with the goal of creating large-scale farm ing units. In 2013, the authorities issued documents encouraging farmers to transfer land-use rights to large-scale grain production households, fam ily farms,or farmer cooperatives.

Ling Jihe, a farmer from Nanchang,Jiangxi Province, is a pioneer in this feld. In 2009, Ling founded his agricultural development company and now deals w ith around 18,000 mu (an area roughly equal to 12 square kilometers) of land. After collecting land from farmers, Ling employs effcient producers to farm and has introduced intensive management and mechanized farm ing, which has massively lowered overhead. Since 2011, Ling has been able to send an annual bonus to the farmers every year—this year bonuses totaled 2.28 m illion RMB. At f rst, many people thought Ling's annual bonus was just a publicity stunt, but after fve years, they adm it that there m ight be something to this new land-transfer model.

But it's not all good news. Zhu states that there are risks, and these hint at some potentially devastating problems. The f rst relates to people deciding to grow things other than grain (which is both less risky and more necessary when it comes to feeding more mouths). In order to make more money from the land,many choose to grow non-grain products, and some even build factories, golf courses, or resorts.

The second is that land transfer increases production costs, so it may thus cause a raise in the price of agricultural products. “To guard against these risks, the government needs to enhance regulations and supervision, prohibiting nonagriculture projects and peop le not growing grain. We also need to prevent people deliberately infating land prices during the transfer process,” says Zhu.

At the same time, many farmers feed reluctant to transfer their land because they worry that they're giving up security. Even if the problem of land fragmentation is solved smoothly, some peop le worry that it will result in a surp lus labor force in the countryside Zhu says these fears, unfortunately, are not groundless.

But, ultimately, time will be the ultimate arbiter of whether China can control the risks of patching the country's farm land back together.

- SUN JIAHUI (孙佳慧)

ORGANIC AWAKENING

China is a land of food safety landmines: exploding hormoneoverdosed watermelons, fake squid made from toxic plastic, clenbuterolinjected pork made to look like beef, and of course, the infamous melam ine-laced baby m ilk powder that even today has rendered “safe”m ilk powder from Hong Kong or overseas a valuable asset on the underground market. Given that food safety issues are a very real and daily concern for most Chinese, it's understandable that some form of the organic food movement would take root in Chinese soil.

However, those expecting it to resemble the Western concept ought to realize that the pressures Chinese consumers face have created a rather different movement.

Where sustainability, environmental impact, and even identity politics color the preferences of Western consumers, food safety is, by and large, the only concern for many Chinese buyers,and rather than focusing primarily on pesticide usage, the chief concern is that food has been tainted by pollution. But there are, of course,wide variances between producers and consumers, and even among different farms, as Beijing-based environmental engineer and restaurateur Tristan Macquet found when he began taking trips to visit farms around the capital in an effort to source organic produce.

“O rganic is mainly about practice—it's what you are putting in the soil,it's what you add to the plant, it's the kind of seeds you grow, it's all these practices. You need to be sure about the soil and the water, that's one of the main concerns in China, with over a third of the land unusable, much of it heavily polluted by factories,”Tristan told TWOC. “You could be the best farmer ever, but if the soil is a wasteland it doesn't make a difference.”

He recounted one instance when visiting a farm which had a number of organic practices but was located opposite a factory and the proprietors didn't know what the factory produced. “So in addition to the soil and water, it can be a problem if you add too many pesticides. It's quite rare to fnd organic food that ticks all the boxes here,” he says. “Environmental protection is often a byproduct; the consumer doesn't care about that, for now at least.”

China does have formal standards for organic certif cation from the M inistry of Agriculture, though testing for these is farmed out to third parties like the China O rganic Food Certif cation Center. This classif cation system has frequently come under f re for solely testing the end-product rather than the actual practices. No doubt a large part of this concern is standardization; testing a piece of fruit for certain specif c toxins is something that can be objectively assessed w ithout requiring an army of inspectors, each operating to the same standards. Un fortunately,this method doesn't necessarily live up to those with high expectations of organic standards regarding practices,and it also operates in a closed environment—suspicious consumerscan't see and understand testing that occurs in a closed-off lab in the same way they cou ld understand a farm's practices.

Where much of the organic movement in the West is focused on issues regarding genetically modifed (GM) food, this concern in some ways is conspicuously absent from the organic scene in China. This is not for any lack of public concern. M ost genetically modifed food, at least technically, is off the table in China for now, both fguratively and literally (though there are notable excep tions such as certain strains of tomatoes,bell peppers and animal feed. In addition, plenty of im ported soybean is GM). Chinese researchers are at the cutting edge of GM research and few doubt that the authorities wou ld like to be able to roll out more GM food options to deal w ith food security and climate issues (via hardier crops), while boosting China's competitive edge. But the public—with understandably heightened suspicions regarding food safety—remains im placably opposed.

So technically, most GM food is banned in China, but given the fact that “genetic modif cation” is in itself a disputed term and that China has often struggled to bring wayward farmers into line, one could argue that banned GM food has probably already breached the borders.

G reenpeace certain ly thinks so—and with pretty good reason. W hen the organization conducted an eight-month p robe in north China's Liaoning Province in 2015, it found that 20 of 21 sam ples of corn found in supermarkets contained strains of GM corn prohibited under the ban.

It seem s p robable, almost certain,that GM food is already widely consumed in China, though when untangling the com plexities of the situation on the ground, both farm ing practices and consumer p references demonstrate the diff culties of embracing any “pure” organic concept.

As M acquet points out: “Consumers want food that looks a certain way. Carrots shou ld be straight, not bent;apples are encased in foam bubbles so they don't touch each other, as this is seen as a bad thing, regardless of the environmental consequences of the packaging. Two carrots m ight be w rapped in clear plastic. Nobody wants vegetables that look ugly or dirty.”

A big part of the food safety issue, of course, lies with farmers. If a farmer fnds that pesticide improves his crop yield, many will take a simple line of reasoning and assume that by doubling the amount of pesticide,yields will further improve and they will make money. This, in a nutshell is at the heart of the problem of food safety in China.

There are, however, very small numbers of both farmers and consumers that recognize crucial principles of safe farm ing, though often they are one and the same—Macquet and other people in the organic movement all described various cases of peop le going so far as to quit their jobs, sometimes for specifc health reasons, so they could grow their own food on a farm. Rather than selling the food commercially, they often only sell or give the food to friends and fam ily. “I had one farmer (who only supplies friends) tell me that it's already too late for this generation, but he was willing to give some organic food to my kid,” M acquet said, while adm itting that he focuses more on sourcing organic food for his child than for himself, as it is too diffcult t get it for every meal.

“I am not an organic purist,”Macquet says. “I, personally, think it' not possible here for all the practices to be 100 percent organic, though there are some w ith better practices and that's what I focus on.”

- DAVID DAWSON

MATTERS OF IMPORT

Earlier this year, a Chinese company tried to buy a chunk of Australia the size of Wales (about the size of Kentucky, to provide an American example). The 250 m illion AUD purchase of the beef station was blocked by Australian regulators, who found security reasons to reject the sale that covered one percent of Australia's gargantuan landmass. Plenty of pundits pointed out, however, that while Australia's foreign investment review board is theoretically independent of the powers-that-be, politically speaking, rejecting the deal was easily the more palatable option in the current electoral climate.

The entire affair can be seen as a m icrocosm f China's efforts to secure agricultural land orldwide; while seen as necessary by the Chinese authorities, it's a massive endeavor that requires Chinese companies to navigate the political and social systems of other cultures, often w ith m ixed results. From Africa to South America,Australia and Europe, Chinese companies are doing their best to secure local farm assets. This, of course, prompts the question as to why China is so desperate to buy foreign food and get its hands on foreign farms.

China's issues with food security are entwined with its history. Fam ines, be they natural or manmade, have plagued successive dynasties and governments to such an extent that even today ensuring the nation has enough food, at stable prices, is a key concern of the authorities—so much so that China keeps a “strategic pork reserve” of both frozen pork and live pigs to deal with market fuctuations. It's just one examp le of food security anxiety in the halls of power,which manifests in a number of policies, such as those geared toward self-suffciency in grain production. The Communist Party of China has,ever since its inception, had a heavy emphasis on agriculture in its key policies.

Beyond the history and political considerations, however, is the raw business case for acquiring agricultural assets. Over a billion people live in China and a large proportion of them have seen signifcant rises in living standards over the past few decades. Demand from the new Chinese m iddle class is changing consumption habits to resource-intensive models. This, combined w ith land degradation and urbanization, is why over the last few decades China has become a net importer rather than exporter of various kinds of foods, such as grain. The diffculties of gathering accurate statistics over such a large country mean estimates on when this occurred for each type of food vary, but what is agreed is that China's fragmented farming model—where small farmers own small plots of land—is now inadequate in terms of both supplying enough food and in being able to live up to food safety standards.

Simp ly put, for some time now,China hasn't been able to feed its population without outside help.

This of course means there is an impressive chance to make money for Chinese companies, which have far greater access to Chinese markets than foreign competitors, but they need to source food elsewhere, and unlike their Western counterparts, Chinese companies haven't always had a lot of experience dealing with foreign legal systems and work practices, let alone potentially xenophobic local sentiment.

Sometimes, all it takes is a whiff of a deal to set the media frenzy on edge. In September 2013, a spate of news reports indicated that a Chinese company had purchased, or agreed to rent for 50 years, three m illion hectares of farm land in Ukraine. Given the recent civil war in Ukraine, it is perhaps fortunate that the deal in reality was far more modest—the company came out with an announcement that the reports were inaccurate and that there was only a far smaller deal for 3,000 acres. The deal was just one of many that, when probed, indicated in all probability that Chinese companies had bitten off more than they could chew and had to settle for less.

There are plenty of success stories of Chinese companies purchasing farm land overseas, though smaller buys have p roven much easier to successfully cement. Large Chinese com panies may prefer to be able to scoop up big deals in one fell swoop,but the reality on the ground shows that these kinds of deals are far more likely to prom pt a backlash.

In the period since the failed beef deal and am id w idesp read media reports expressing anxiety over foreign purchases, Australia's foreign investment review board dropped its threshold for investigating investments from 252 m illion to 15 m illion AUD.

This was not a direct result of the deal of course, but can't be viewed in isolation from it, nor the recent signing of a free trade arrangement between the two nations.

Australia has been a popular destination for Chinese agriculture investments, and Chinese investment in general. According to a report,jointly released in April 2016 by market research company KPMG and the University of Sydney, Chinese investment in Australia's agricu lture sector stood at 375 m illion AUD in 2015, and in term s of overall investment, Australia has been the second largest recipient of aggregated global direct investment from China behind the US over the last decade.

It is, of course, im portant to separate trade from investment. While trade headlines demonstrate China's deep economic ties with developing nations,when it comes to investment, China overwhelm ingly prefers to purchase assets in developed countries. In both cases, however, the US is by far China's largest partner. In 2015, the US department of Agriculture pointws out in a report that, “The United States accounted for over 24 percent of the value of China's agricultural im ports during 2012-2013, a larger share than any other country. US agricultural sales to China doub led from 2008 to 2012, reaching nearly 2 billion USD in annual sales. China has overtaken Japan, Mexico, and Canada to become the leading export market for US agricultural p roducts.”

It was an interesting insight into the ways in which the world's two most powerful nations—for all the tension and disagreements that appear in media—are often, econom ically speaking, joined at the hip. And this is only likely to increase in future, as the report pointed out: “W hile bulk commodities remain predom inant in China's agricultural im ports, evolvin consumer tastes and increased purchasing power are stimulating demand for higher value p roducts. Im ports of wine, beer, cheese, breads cookies, extracts of coffee and tea, and ice cream are grow ing rapid ly.”

China's grow ing appetite certainly causes consternation in plenty of quarters—a recent campaign including celebrities such as Arnold Schwarzenegger targeted Chinese consumers, urging them to cut down on their meat intake for the sake of the environment—but in many ways it certainly seems like one place wher Chinese and other consumers all ove the world are com ing together is the dinner table. - D.D.

——舒城舒茶人民公社