卵胎生入侵种食蚊鱼的两性异形和雌性繁殖输出

樊晓丽,林植华,胡雄光,雷焕宗,李 香

丽水学院生态学院, 丽水 323000

卵胎生入侵种食蚊鱼的两性异形和雌性繁殖输出

樊晓丽,林植华*,胡雄光,雷焕宗,李香

丽水学院生态学院, 丽水323000

摘要:检测了卵胎生入侵种食蚊鱼(Gambusia affinis)繁殖期个体大小和形态特征的两性异形以及雌性繁殖输出。结果表明,繁殖期,雌性个体的数量显著大于雄性个体,雌性个体的体长显著大于雄性个体,食蚊鱼属于偏向雌性的两性异形。以体长为协变量的One-way ANCOVA及后续的Tukey′s检验显示,特定体长食蚊鱼的雌性个体的头宽、眼间距、体宽和体重均显著大于雄性个体;头长和尾鳍长的两性间差异不显著。6个形态特征变量的主成分分析(Eigenvalue ≥ 1)发现,前2 个主成分共解释65.1%的变异。头宽、眼间距、体宽和体重在第一主成分有较高的正负载系数(解释45.4%变异),头长在第二主成分有较高的负负载系数(解释19.7%变异)。食蚊鱼的繁殖输出与母体个体大小的线性回归显示,窝仔数和窝仔重均与母体体长、体重呈显著的正相关;食蚊鱼的繁殖输出与母体局部特征的线性回归显示,窝仔数和窝仔重均与母体头宽、眼间距和体宽呈显著的正相关。窝仔数与后代个体的平均体长呈显著的正相关、与后代个体的平均体重相关不显著,后代个体大小与数量不发生权衡。食蚊鱼繁殖期的性别比例、个体大小和局部形态特征的两性异形受生育力选择、性选择、生态位分化、食物竞争等多种选择压力的作用,也有利于该物种种群扩张和快速入侵。

关键词:食蚊鱼;卵胎生;两性异形;性别比例;繁殖输出

食蚊鱼(Gambusiaaffinis)是原产于北美洲大西洋沿岸低洼地和沟渠等的一种暖水性(25—30℃)营卵胎生的小型硬骨鱼类,隶属于鳉形目(Cyprinodontiformes),食蚊鱼属(Gambusia)[19]。在繁殖期,性成熟雄性个体的臀鳍特化形成交配器,卵子在雌性体内受精并发育成仔鱼产出[20- 21],一尾雌鱼能同时贮存多个雄性个体的精子发生多批次产仔,产出仔鱼能够自由游动和摄食[22- 24]。1927 年食蚊鱼被引入我国[25],目前普遍存在于在中国长江以南地区的水体中[26],甚至出现在云南高原湖泊中[27]。全球范围来看,该物种已扩散到全球温带和热带地区(除南极洲以外)[28- 29]。大量研究表明,入侵种食蚊鱼通过竞争和捕食等机制对当地土著种和生物多样性产生了严重影响[30- 34]。因此,食蚊鱼已经被纳入由世界自然保护联盟公布的全球100种最具威胁的外来入侵种名单[35]。

本文以食蚊鱼为材料,检测繁殖期形态特征的两性异形,利用其卵胎生的特点实现雌性繁殖特征的有效收集,探讨该物种两性异形的形成原因,以及食蚊鱼的全球入侵和扩散的相关机制。

1材料与方法

1.1实验动物的采集与形态测定

2014年3月5日—10日,11:00—13:00,从浙江省丽水学院持久性池塘(28°27′N,119°53′E)的水面表层用聚乙烯加工的手捞网(网目3 mm × 3 mm)捕获食蚊鱼(N=92),带回两栖爬行动物实验室,混养在25℃人工气侯室内的塑料箱(70 cm× 50 cm× 40 cm)中,箱内放置一些金鱼藻(Ceratophyllumdemersum)。

用Sartorius分析天平分别称取成鱼的体重(±0.001 g, 雌鱼为产前体重),用Sony DSC-T100数码相机记录亲鱼形态,用ImageJ 1.44p软件测定亲鱼的体长(从吻端到尾椎终端的距离)、头长(由吻端到鳃盖骨后缘的水平距离)、头宽(眼眶后缘处头部的水平宽度)、眼间距(左右两侧眼背缘之间的最小距离)、体宽(背鳍起始处左右两侧身体之间的距离)以及尾鳍长(尾鳍起始处到尾鳍末端的距离)(± 0.01 mm)。记录性别,臀鳍的第3、4、5鳍条延长特化形成具有固着小勾、感觉小棘和输精管沟的交配器(也称生殖足)的个体为雄鱼[20],躯干两侧具有黑色胎斑的个体为雌鱼[36]。

1.2雌性繁殖输出

怀仔雌鱼单独饲养在透明塑料碗(直径约150 mm)内,水深120 mm,放置一定数量金鱼藻,碗口盖1 mm网眼的防逃网罩,每天定量喂食鱼饲料。仔鱼一旦产出,记录产仔数,随机挑出10条仔鱼记录其体长、体重,同时称取雌鱼产后体重(±0.001 g)。实验结束后,实验动物放回原先捕获水体。

1.3数据分析

所有数据的统计分析用Statistica 统计软件包完成。数据在作进一步统计分析前检验其正态性(Kolmogorov-Smirnov test)和方差同质性(F-max test)。经检验,部分形态学数据经ln转换后符合参数统计条件。用线性回归、方差分析(One-way ANOVA)、协方差分析(One-way ANCOVA)、主成分分析等处理和比较相应的数据,比较矫正平均值前检验斜率的均一性。文中涉及的非参数统计为G-检验。描述性统计值用平均值 ± 标准误(范围)表示,显著性水平设置为α=0.05。

图1 食蚊鱼雌雄个体体长的频数分布图 Fig.1 Body length frequency distributions of female and male mosquitofish, G. affinis

2结果

2.1个体大小和局部形态特征的两性异形

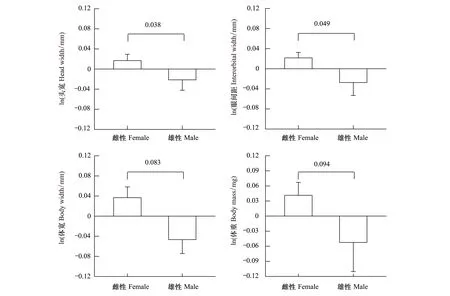

共采集食蚊鱼92尾,雌性62尾,均有产仔行为,雄性30尾,均有延长具勾的臀鳍,雌性个体的数量显著大于雄性个体(G-检验,G=11.37,df=1,P<0.001)。记录了其中38尾雌性个体完整的形态和繁殖特征,该数据用于形态特征的比较和分析,食蚊鱼雌雄形态特征的描述性统计见表1。数据经ln转换后,符合参数统计的条件。One-way ANOVA显示,雌性个体的体长显著大于雄性个体(图1,表1),最小的雌性个体大于最大的雄性个体;以体长为协变量的One-way ANCOVA及后续的Tukey′s 检验显示,特定体长食蚊鱼的雌性个体的头宽、眼间距、体宽和体重均显著大于雄性个体(allP<0.001,图2,表2);头长和尾鳍长的两性间差异不显著(表1)。6个形态特征变量的主成分分析(Eigenvalue ≥ 1)发现,前2 个主成分共解释65.1%的变异(表3)。头宽、眼间距、体宽和体重在第一主成分有较高的正负载系数(解释45.4%变异),头长在第二主成分有较高的负负载系数(解释19.7%变异)。

表1 食蚊鱼形态特征的描述性统计值

表中数据用平均值±标准误(范围)表示;表中显示One-way ANOVA(体长)或ANCOVA(其余形态变量以体长为协变量)的F值和显著性水平(数据经ln转换);F:成年雌体;M:成年雄体

图2 以体长为自变量的食蚊鱼头宽、眼间距、体宽和体重的回归剩余值(数据经ln转换)Fig.2 Mean values (± SE) for regression residuals of head width, interorbital width, body width and body mass against body length of G. affinis图中数值表示两性间回归剩余值的差值

形态变量Morphologicalvariables平均值Mean标准误Standarderror最小值Minimum最大值Maximum体长Bodylength/mm35.660.71028.3347.62产仔后体重Postpartumbodymass/mg503.9833.243233.201107.20窝仔重Littermass/mg151.8210.82557.60393.20窝仔数Littersize21.211.3031047仔鱼平均体长Meanlitterbodylength/mm7.010.0806.128.23仔鱼平均体重Meanlitterbodymass/mg7.230.3013.9010.94

2.2雌体繁殖输出

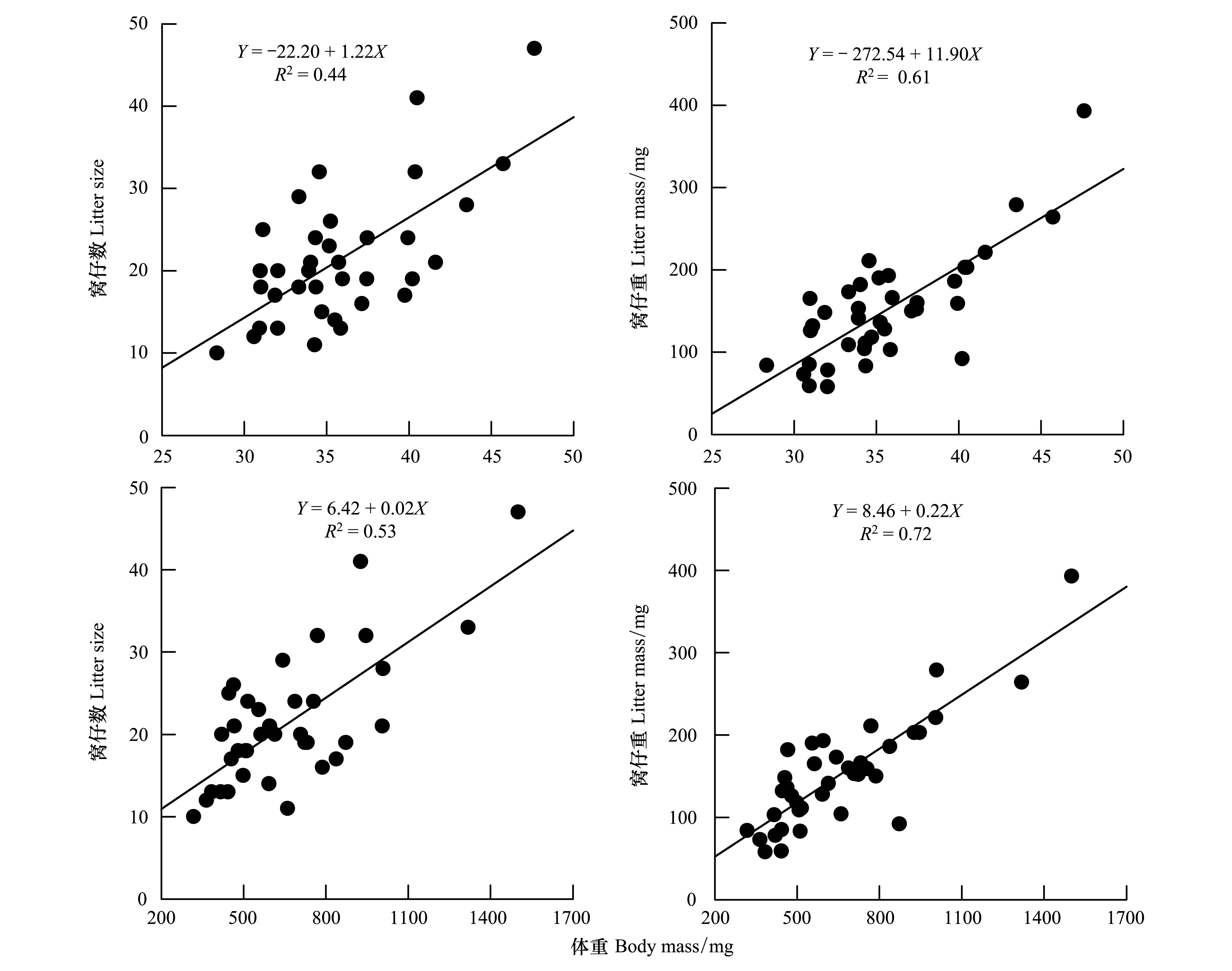

食蚊鱼的繁殖输出与母体个体大小的线性回归显示(图3),窝仔数与母体体长(F1, 36=28.24,P<0.0001)、体重(F1, 36=39.94,P<0.0001)呈显著的正相关;窝仔重与亲本的体长(F1, 36=56.60,P<0.0001)、体重(F1, 36=92.31,P<0.0001)呈显著的正相关。

食蚊鱼的繁殖输出与母体局部特征的线性回归显示(图4),窝仔数与母体头宽(F1, 36=15.32,P<0.0001)、眼间距(F1, 36=18.64,P<0.001)和体宽(F1, 36=21.80,P<0.0001)呈显著正相关;窝仔重与母体头宽(F1, 36=35.56,P<0.0001)、眼间距(F1, 36=28.88,P<0.001)和体宽(F1, 36=48.09,P<0.0001)呈显著正相关。

窝仔数与后代个体的平均体长呈显著的正相关(r2=0.11,F1, 36=4.45,P<0.042, 图5)、与后代个体的平均体重相关不显著(r2=0.01,F1, 36=0.39,P=0.536)。

表36个成体形态特征变量的主成分分析的负载系数

Table 3Loading of the first two axes of a principal component analysis on six adult morphological variables

形态变量Morphologicalvariables负载系数FactorloadingPC1PC2头长Headlength-0.005-0.967头宽Headwidth0.756-0.357眼间距Interorbitalwidth0.758-0.319体宽Bodywidth0.7970.044尾鳍长Caudalfinlength0.5880.115体重Bodymass0.7730.005解释变异Varianceexplained45.4%19.7%

用变量与体长的回归剩余值去除大小差异的影响,对每个主成分有主要贡献的变量用黑体注明

图3 食蚊鱼的繁殖输出与母体个体大小的相关性Fig.3 Correlation between female body size and reproductive output of G. affinis

图4 食蚊鱼的繁殖输出与母体局部特征的相关性Fig.4 Correlation between local features and reproductive output of G. affinis

图5 食蚊鱼窝仔数与仔鱼平均体长的相关性 Fig.5 Correlation between litter size and mean litter body length of G. affinis

3讨论

繁殖期食蚊鱼性别比例偏离1∶1,雌性个体显著多于雄性个体,这与已有结果一致[20],雄性个体一旦完成授精后就从种群中消失,这可能是完成繁殖后,给雌性个体留下更多的环境资源和空间[22],有利于雌性个体提高后代的数量和成活率,可能是造成该物种种群扩张和快速入侵的原因之一。

鱼类普遍存在的个体大小的两性异形,主要受生育力选择、性选择、生态位分化、食物竞争等多种选择压力的作用[5, 14, 16, 37- 39]。食蚊鱼的雌性个体显著大于雄性(表1,图1),首先与食蚊鱼的摄食和生长的性别分化有关,食蚊鱼在6 日龄臀鳍开始分化时,雄鱼的摄食量和生长速度开始低于雌鱼,且随着日龄的增加差异加大[40],雄性个体在性成熟后生长便接近于停滞[25],此阶段将身体主要能量用在对雌鱼的争夺及交配行为上[25, 41- 44]。其次,食蚊鱼在生长发育、性成熟和能量分配等应对策略上的性别差异在一定程度上促进了生态位的分化、减少了种内的资源竞争,使种群内的雌鱼有更多机会获得生长发育所需的食物资源,这也为其生态入侵提供了有利的条件[1, 40, 45]。再次,食蚊鱼的繁殖输出(窝仔数与窝仔重)均与雌体大小(体长和体重)呈显著的正相关(图3),这一结果与已有研究[20]的实验结果相吻合,也类似于卵胎生密点麻蜥(Eremiasmultiocellata)[46]和蝘蜓(Sphenomorphusindicus)[47]等动物的情况。据此可以推断:(1)食蚊鱼增大繁殖输出的主要途径是增加窝仔数及相应的窝仔重;(2)当食物可得性和雌体贮能状况不成为限制因素时,雌体大小是繁殖输出的主要决定因子。这也意味着雌性亲鱼个体越大,产下后代仔鱼也越多(或质量越好),这正如先前报道的许多其他鱼类一样[5, 48- 50]。故生育力选择是促使食蚊鱼大个体雌性形成的选择压力。

在本研究中,特定体长的食蚊鱼雌性个体的头宽与眼间距均显著大于雄性个体(表1,图2)。雌性个体拥有较宽头部和眼间距有利于雌性个体获取更多的食物资源来满足繁殖期连续多次产仔的能量需求,配偶竞争中更多的受精机会[51]。母体内的胚胎发育过程中重量和体积的增加,使得腹腔空间成为增加繁殖输出的限制因子[47]。食蚊鱼雌性个体的体宽显著大于雄性个体(表1,图2),因而形成较大的腹腔容量,雌性个体通过局部特征的扩大来增加腹腔容量,提高怀仔量,从而增加雌性个体的繁殖输出,这同时也反映了生育力选择对局部特征两性异形的影响[7- 8]。食蚊鱼繁殖输出(窝仔数与窝仔重)也与雌体的头宽、眼间距和体宽这3个局部形态特征呈显著的正相关(图4),进一步证实了食蚊鱼局部形态特征与雌性个体繁殖特征的相关性。

初产仔鱼个体大小通常直接影响到它的存活、生长速度、竞争能力等一系列的适合度,故它被认为是卵胎生(或胎生)生物生活史特征的一个重要参数[52- 55]。在本研究中,食蚊鱼的窝仔数与初产仔鱼个体大小呈显著正相关(图5),这表明雌体食蚊鱼生育力的提高,并不以减少后代的个体大小为代价,即卵胎生食蚊鱼的后代个体大小与数量之间不发生权衡,这也是食蚊鱼种群扩张和快速入侵的一个优势。

参考文献(References):

[1]Henderson B A, Collins N, Morgan G E, Vaillancourt A. Sexual size dimorphism of walleye (Stizostedionvitreumvitreum). Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 2003, 60(11): 1345- 1352.

[2]Casselman S J, Schulte- Hostedde A I. Reproductive roles predict sexual dimorphism in internal and external morphology of lake whitefish,Coregonusclupeaformis. Ecology of Freshwater Fish, 2004, 13(3): 217- 222.

[4]Takada M, Tachihara K. Comparisons of age, growth, and maturity between male and female, and diploid and triploid individuals inCarassiusauratusfrom Okinawa- jima Island, Japan. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems, 2009, 19(7): 806- 814.

[5]林植华, 雷焕宗. 似刺鳊鮈的两性异形和雌性个体生育力. 上海交通大学学报: 农业科学版, 2006, 24(2): 138- 142.

[6]林植华, 雷焕宗. 黄颡鱼的两性异形和雌性繁殖特征. 动物学杂志, 2004, 39(6): 13- 17.

[7]林植华, 雷焕宗, 陈利丽, 樊晓丽, 鲍正华, 高炳让. 棒花鱼形态特征的两性异形和雌性个体生育力. 四川动物, 2007, 26(4): 910- 913.

[8]樊晓丽, 林植华, 卢静, 邱月, 陈策, 高翼军, 戚丹锋. 沙塘鳢形态特征的两性异形和雌性个体生育力. 上海交通大学学报: 农业科学版, 2009, 28(6): 588- 591, 623- 623.

[9]Takahashi T, Ota K, Kohda M, Hori M. Some evidence for different ecological pressures that constrain male and female body size. Hydrobiologia, 2012, 684(1): 35- 44.

[10]樊晓丽, 林植华, 丁先龙, 朱吉峰. 鲶鱼和胡子鲶的两性异形与雌性个体生育力. 生态学报, 2014, 34(3): 555- 563.

[11]Kelly C D, Folinsbee K E, Adams D C, Jennions M D. Intraspecific sexual size and shape dimorphism in an Australian freshwater fish differs with respect to a biogeographic barrier and latitude. Evolutionary Biology, 2013, 40(3): 408- 419.

[12]林植华, 雷焕宗, 林植云, 华和亮. 花的两性异形和雌体繁殖输出. 上海交通大学学报: 农业科学版, 2005, 23(3): 284- 288.

[13]徐德钦, 林植华, 雷焕宗. 温州厚唇鱼形态特征的两性异形和雌性个体生育力. 上海交通大学学报: 农业科学版, 2006, 24(4): 335- 340.

[14]Parker G A. The evolution of sexual size dimorphism in fish. Journal of Fish Biology, 1992, 41(Supplement sB): 1- 20.

[15]Pyron M, Pitcher T E, Jacquemin S J. Evolution of mating systems and sexual size dimorphism in North American cyprinids. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 2013, 67(5): 747- 756.

[16]Herler J, Kerschbaumer M, Mitteroecker P, Postl L, Sturmbauer C. Sexual dimorphism and population divergence in the Lake Tanganyika cichlid fish genusTropheus. Frontiers in Zoology, 2010, 7: 4- 14.

[17]Sims D W. Tractable models for testing theories about natural strategies: foraging behaviour and habitat selection of free-ranging sharks. Journal of Fish Biology, 2003, 63(Supplement s1): 53- 73.

[18]冯东岳. 许氏平鲉繁殖生物学及人工养殖技术的研究[D]. 青岛: 中国海洋大学, 2003.

[19]Lounibos L P, Frank J H. Biological control of mosquitoes // Rosen D, Bennett F D, Capinera J L, eds. Pest Management in the Subtropics. Andover: Intercept, 1994: 395- 407.

[20]郑文彪, 潘炯华. 食蚊鱼的生殖特性的研究. 动物学研究, 1985, 6(3): 227- 231.

[21]Pyke G H. A review of the biology ofGambusiaaffinisandG.holbrooki. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries, 2005, 15(4): 339- 365.

[22]Krumholz A L. Reproduction in the western mosquitofish,Gambusiaaffinisaffinis(Baird & Girard), and its use in mosquito control. Ecological Monographs, 1948, 18(1): 1- 43.

[23]Waples R S. Sperm storage, multiple insemination, and genetic variability in mosquitofish: a reassessment. Copeia, 1987, 1987(4): 1068- 1071.

[24]Koya Y, Kamiya E. Environmental regulation of annual reproductive cycle in the mosquitofish,Gambusiaaffinis. Journal of Experimental Zoology, 2000, 286(2): 204- 211.

[25]潘炯华, 苏炳之, 郑文彪. 食蚊鱼(Gambusiaaffinis)的生物学特性及其灭蚊利用的展望. 华南师院学报: 自然科学版, 1980, (1): 117- 138.

[26]李振宇, 解焱. 中国外来入侵种. 北京: 中国林业出版社, 2002: 88- 88.

[27]杨君兴, 陈银瑞. 抚仙湖鱼类生物学和资源利用. 昆明: 云南科技出版社, 1995.

[28]Stochwell C A, Week S C. Translocations and rapid evolutionary responses in recently established populations of western mosquitofish (Gambusiaaffinis). Animal Conservation, 1999, 2(2): 103- 110.

[29]陈国柱, 林小涛, 陈佩. 食蚊鱼(Gambusiaspp.)入侵生态学研究进展. 生态学报, 2008, 28(9): 4476- 4485.

[30]Goodsell J A, Kats L B. Effect of introduced mosquitofish on pacific treefrogs and the role of alternative prey. Conservation Biology, 1999, 13(4): 921- 924.

[31]Leyse K E, Lawler S P, Strange T. Effects of an alien fish,Gambusiaaffinis, on an endemic California fairy shrimp,Linderiellaoccidentalis: implications for conservation of diversity in fishless waters. Biological Conservation, 2004, 118(1): 57- 65.

[32]David L R, Craig A S. Assessment of potential impacts of exotic species on populations of a threatened species, White Sands pupfish,Cyprinodontularosa. Biological Invasions, 2006, 8(1): 79- 87.

[33]Smith G R, Boyd A, Dayer C B, Winter K E. Behavioral responses of American toad and bullfrog tadpoles to the presence of cues from the invasive fish,Gambusiaaffinis. Biological invasion, 2008, 10(5): 743- 748.

[34]Schleier J J III, Sing S E, Peterson R K D. Regional ecological risk assessment for the introduction ofGambusiaaffinis(western mosquitofish) into Montana watersheds. Biological Invasions, 2008, 10(8): 1277- 1287.

[35]Lowe S, Browne M, Boudjelas S, De Poorter M. 100 of the world′s worst invasive alien species —A selection from the global invasive species Database. Invasive Species Specialist Group, World Conservation Union, 2000.

[36]刘丽娟, 童晓立. 食蚊鱼对水生昆虫的捕食选择性研究. 华南农业大学学报, 2012, 33(1): 44- 47.

[37]Shine R. Ecological causes for the evolution of sexual dimorphism: a review of the evidence. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 1989, 64(4): 419- 464.

[38]Chu C Y C, Lee R D. Sexual dimorphism and sexual selection: a unified economic analysis. Theoretical Population Biology, 2012, 82(4): 355- 363.

[39]Winkler J D, Stölting K N, Wilson A B. Sex-specific responses to fecundity selection in the broad-nosed pipefish. Evolutionary Ecology, 2012, 26(3): 701- 714.

[40]曾祥玲, 林小涛, 刘毅. 摄食水平对不同性别食蚊鱼仔幼鱼生长发育的影响. 水生生物学报, 2011, 35(3): 384- 392.

[41]Shakuntala K. Effect of feeding level on the rate and efficiency of food conversion in the cyprinodon fishGambusiaaffinis. Ceylon Journal of Science (Biological Sciences), 1977, 12(2): 177- 184.

[42]Hughes A L. Growth of adult mosquitofishGambusiaaffinisin the laboratory. Copeia, 1986, 1986(2): 534- 536.

[43]高书堂, 刘灼见, 邓青. 食蚊鱼的饲养、生长、生殖情况概述. 淡水渔业, 1995, 25(6): 17- 19.

[44]陈佩, 陈国柱, 林小涛, 许忠能. 食蚊鱼昼夜摄食节律观察. 生态科学, 2008, 27(6): 483- 489.

[45]García-Berthou E. Food of introduced mosquitofish: ontogenetic diet shift and prey selection. Journal of Fish Biology, 1999, 55(1): 135- 147.

[46]刘遒发, 黄族豪, 李仁德. 密点麻蜥民勤种群的繁殖研究 // 中国动物学会两栖爬行动物学分会2005年学术研讨会暨会员代表大会论文集. 2005: 147- 154.

[47]计翔, 杜卫国. 蝘蜓头、体大小的两性异形和雌体繁殖. 动物学研究, 2000, 21(5): 349- 354.

[48]Elgar M A. Evolutionary compromise between a few large and many small eggs: comparative evidence in teleost fish. Oikos, 1990, 59: 283- 287.

[49]Jonsson N, Jonsson B. Trade-off between egg mass and egg number in brown trout. Journal of Fish Biology, 1999, 55(4): 767- 783.

[50]Billman E J, Belk M C. Effect of age-based and environment-based cues on reproductive investment inGambusiaaffinis. Ecology and Evolution, 2014, 4(9): 1611- 1622.

[51]张永普, 计翔. 北草蜥个体发育过程中头部两性异形及食性的变化. 动物学研究, 2000, 21(3): 181- 186.

[52]Reznick D. Grandfather effects′: the genetics of interpopulation differences in offspring size in the mosquito fish. Evolution, 1981, 35(5): 941- 953.

[53]Meffe G K. Embryo size variation in mosquitofish: optimality vs plasticity in propagule size. Copeia, 1987, 1987(3): 762- 768.

[54]Meffe G K. Offspring size variation in eastern mosquitofish (Gambusiaholbrooki: Poeciliidae) from contrasting thermal environments. Copeia, 1990, 1990(1): 10- 18.

[55]Reznick D, Schultz E, Morey S, Roff D. On the virtue of being the first born: the influence of date of birth on fitness in the mosquitofish,Gambusiaaffinis. Oikos, 2006, 114(1): 135- 147.

Sexual dimorphism and female reproductive outputs of the ovoviviparous and invasive mosquitofishGambusiaaffinis

FAN Xiaoli, LIN Zhihua*, HU Xiongguang, LEI Huanzong, LI Xiang

CollegeofEcology,LishuiUniversity,Lishui323000,China

Abstract:In this study, we measured the sexual dimorphism in body size and six other mophometrical variables along with the individual fecundity in females of ovoviviparous and invasive mosquitofish Gambusia affinis, collected in Lishui (Zhejiang, eastern China), during the reproductive season. The results showed that the number of adult females was more than that of the males during the breeding season, and the body length of adult females was significantly longer than that of adult males. Therefore, G. affinis is a species with highly female-biased sexual size dimorphism. One-way analysis of variance with body length as a covariate showed significantly higher (P<0.0001) head width, interorbital width, body width, and body mass for G. affinis females than males, while no significant sexual differences were identified based on the head length or caudal fin length. A principal component analysis resolved two components (with Eigenvalues ≥ 1) from six morphometrical variables, accounting for 65.1% of variation in the original data. The first component (45.4% variance explained) had high positive loading for size-free values of head width, interorbital width, body width, and body mass; and the second component (19.7% variance explained) had high negative loading for the size-free value of head length. Analysis of unary linear regression showed that the reproductive outputs (including brood size and mass) of G. affinis positively correlated with the female body length, body mass, head width, interorbital width, and body width. Brood size positively correlated with the average body length of offspring, but there was no correlation between the brood size and the average body mass. No trade-off was identified between the size and number of offspring. Sexual dimorphism in sex ratio, body size, and local characteristics of G. affinis was influenced by a variety of selection pressure parameters, including fecundity selection, sexual selection, niche differentiation, and food competition during the breeding season. Sexual dimorphism also contributed to population expansion and rapid invasion of the species. Our results have provided some basic data for further studies on the evolution mechanisms of fish sexual dimorphism.

Key Words:Gambusia affinis; ovoviviparity; sexual dimorphism; sex ratio; reproductive outputs

基金项目:国家自然科学基金项目(31270443); 浙江省大学生科技创新活动计划(2013R429025)

收稿日期:2014- 12- 03; 网络出版日期:2015- 08- 26

*通讯作者

Corresponding author.E-mail: zhlin1015@126.com

DOI:10.5846/stxb201412032399

樊晓丽,林植华,胡雄光,雷焕宗,李香.卵胎生入侵种食蚊鱼的两性异形和雌性繁殖输出.生态学报,2016,36(9):2497- 2504.

Fan X L, Lin Z H, Hu X G, Lei H Z, Li X.Sexual dimorphism and female reproductive outputs of the ovoviviparous and invasive mosquitofishGambusiaaffinis.Acta Ecologica Sinica,2016,36(9):2497- 2504.