Preparation of Ni/bentonite catalyst and its applications in the catalytic hydrogenation ofnitrobenzene to aniline☆

Yuexiu Jiang ,Xiliang Li,Zuzeng Qin ,2,*,Hongbing Ji,2,*

1 GuangxiKey Laboratory ofPetrochemicalResource Processing and Process Intensi fication Technology,SchoolofChemistry and ChemicalEngineering,GuangxiUniversity,Nanning 530004,China

2 SchoolofChemistry and ChemicalEngineering,Sun Yat-sen University,Guangzhou 510275,China

1.Introduction

Aniline is an aromatic compound which contains an amino group that provides a unique reactivity.This unique reactivity makes aniline an important intermediate for producing polyurethanes,dyes,explosives,pharmaceuticals,and agriculture chemicals[1,2].Catalytic hydrogenation is a promising way to produce aniline because it is easier to control,much safer and has little impact on the environment.Aniline,as previously described,is mainly produced by the catalytic hydrogenation ofnitrobenzene over a variety ofsupported metalcatalysts,such as Pd supported on polymer[3],Cu–Cr–Mo/SiO2[4],Ni/SBA-15[5]and Pd/C[6],either in the vapour or liquid phase.Generally,noble metal catalysts are used for the hydrogenation of nitrobenzene liquid phase to produce aniline[6],and commercially,the reaction is carried out in the vapour phase over copper-based catalysts[7].On the other hand,both the Bechamp reduction and sulphide reduction in the conventional non-catalytic process generate large amounts of waste[8].Major problems,such as the cost of the catalyst and the impact caused by the reaction on the environment,remain unsolved,and the development of greener,cheaper,more effective,and convenientlyhandled catalysts for this hydrogenation process is stillhighly desirable.

Bentonite,with a layer structure containing a larger amount of mesoporous,is a good catalyst supportdue to its strong metalsupport interaction and low cost,and its numerous applications in the catalytic field have been reported[9–12].Based on our previous studies of nitrobenzene catalytic hydrogenation to aniline in a gas–liquid–solid system[13–15],and with the goalofdeveloping a sustainable catalytic process with high ef ficiency,Ni/bentonite catalystswith differentnickel loading amounts were prepared,characterized,and applied for the hydrogenation ofnitrobenzene in the gas phase in a fixed-bed reactor.

2.Experimental

2.1.Preparation of Ni/bentonite catalysts

Ni(NO3)2·6H2O and bentonite were weighed in the mass ratios of m(Ni)/m(bentonite)=0.05,i.e.0.5 g Niand 10.0 g bentonite,and each was dissolved in 100 mlofdeionized water.The bentonite suspension was heated to 70 °Cwith a 200 r·min-1agitation for0.5 h,which ensured the fullswelling of bentonite.Then,the Ni(NO3)2solution was dropped into the bentonite suspension with a 200 r·min-1agitation at 70 °C for 4 h,to obtain a slurry.The slurry was dried at100°C for12 h and then calcined at400°C for 4 h.The obtained catalystwith a Niloading amountof 5 wt%was marked as Ni/bentonite-5.The same procedure was followed to prepare Ni/bentonite catalysts with 10 wt%,15 wt%,20 wt%,and 25 wt%Niloading amounts,and the obtained catalysts were marked as Ni/bentonite-10,Ni/bentonite-15,Ni/bentonite-20,and Ni/bentonite-25,respectively.

2.2.Characterization ofcatalysts

X-ray diffraction(XRD)wasconducted with a Bruker D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer,using Cu Kαradiation(λ=0.154 nm).The average size of the NiO crystallite was estimated from the(200)plane of NiO at 2θ=43.3ousing the Scherrer equation.The NiO crystallite sizes,d(NiO),were converted to the corresponding Nicrystallite sizes after reduction,d(Ni),using the relative molar volumes ofmetallic Niand NiO[16],as show in Eq.(1).

The H2temperature programmed reduction(H2-TPR)experiment was conducted on a TP-5000 multi-function adsorption instrument(Tianjin Xianquan Industry and Trade Development Co.).The X-ray photoelectron spectra of the catalysts were measured by a Thermo ESCA LAB 250X multifunction imaging electron spectrometer(Thermo Fisher Scienti fic Co.,Ltd.)using an Al Kαray as the X-ray source.The weight fraction of Niin the samples was precisely determined by ICPOES using a Perkin Elmer Optima 5300 CV after dissolution of the samples using nitric acid.H2temperature programmed desorption(H2-TPD)was taken on a TP-5080 multi-function adsorption instrument(Tianjin Xianquan Industry and Trade Development Co.Ltd.),About0.10 g Ni/bentonite sample was added into a quartz reactor,flushed at 150°C for 2 h in Ar to remove the physically adsorbed molecules,After that,the sample was cooled to 50°C,and H2was introduced at 30 ml·min-1for 0.5 h for dynamic absorption measurements of H2.Subsequentstatic adsorption tests were performed at0.2 MPa for 1.5 h to insure saturation adsorption of H2.After that,gas desorption experiments were carried out in 30 ml·min-1He(99.999%)in a range of 50–800 °C with a ramp rate of 10 °C·min-1.The amount of gas desorbed was monitored by a thermalconductivity detector(TCD)held at 45°C.

The speci fic surface area,particle size and dispersion of the metallic Niwere calculated based on the chemisorbed H2using Eqs.(2)–(4)[17].

Nimetalspeci fic surface area(SANi):

Nicrystallite size d(Ni0):

where,V1was the volume(ml)of H2chemisorbed atstandard temperature and pressure(STP)conditions to form a monolayer,Wswas the weight of the sample(g),Vmwas the molar volume of H2(22414 ml·mol-1),SF was the stoichiometric factor(Ni:H molar ratio during chemisorption),which is taken as 1,NAwas the Avogadro constant(6.023×1023),RA was the atomic cross-sectional area of Ni(0.0649 nm2),RNiwas the weight fraction of Ni in the sample as determined by ICP,FWNiwas the molecular weight of Ni(58.71 g·mol-1),and PNiwas the density of Nimetal(8.9 g·cm-3).

2.3.Catalytic hydrogenation ofnitrobenzene to aniline

Gas phase catalytic hydrogenation of nitrobenzene to aniline over the Ni/bentonite catalyst was conducted in a fixed-bed reactor that consisted of a quartz reaction tube with an inner diameter of 8 mm and a tube length of 285 mm.Approximately 0.5 g of catalyst was added to the quartz tube and was reduced at 400°C for 1.0 h accompanied by H2(99.999%)flow at a rate of30 ml·min-1.After the catalyst was reduced and cooled to 300°C,nitrobenzene was pumped and vaporized at300°C through a vaporizer,and the catalytic hydrogenation ofnitrobenzene to aniline was conducted at 300°C with a nitrobenzene liquid hourly space velocity(LHSV)between 2.4–7.2 ml·(g cat)-1·h-1.The products were collected at the outlet using a test tube cooled by ice water,and were analysed by an Agilent 4890D gas chromatograph.The conversion of nitrobenzene,and the selectivity and yield of aniline were quantitatively analysed using the peak-area internal standard method with methylbenzene as the internalstandard.

where mNB0,mNB,and mNB1are the totalmassofnitrobenzene consumed in the reaction,the remaining mass ofnitrobenzene in the product,and the mass ofnitrobenzene consumed to produce equivalentaniline in the product,respectively.

3.Results and Discussion

3.1.Physicaland chemicalproperties of Ni/bentonite catalysts

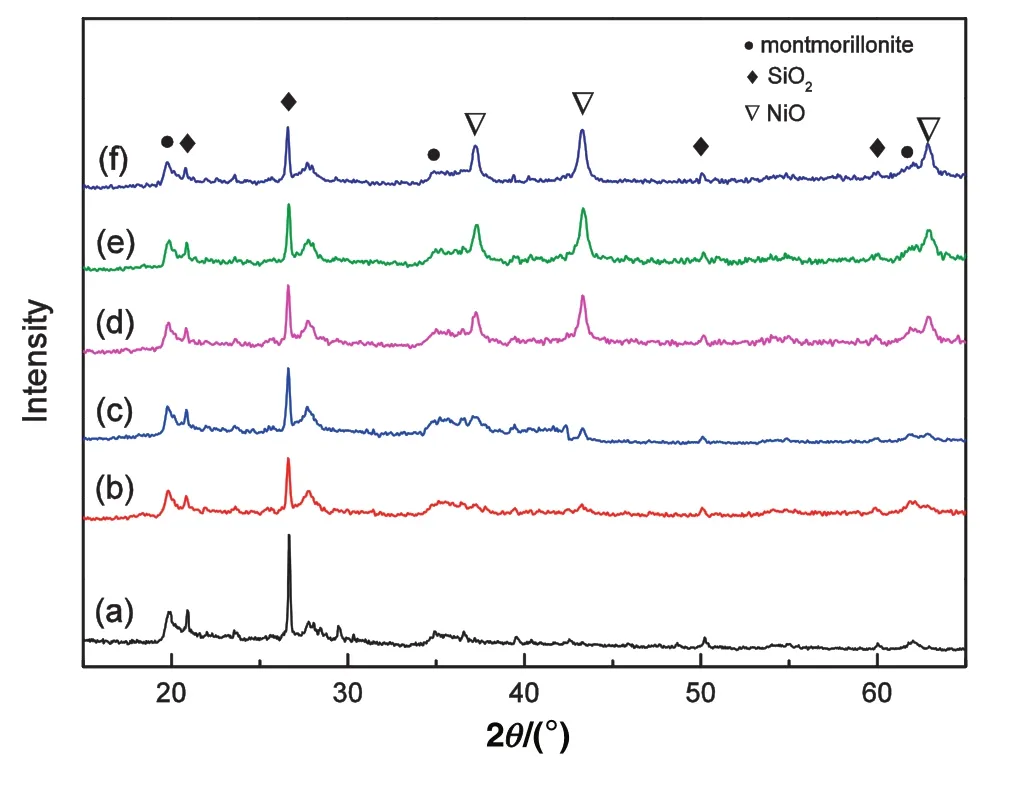

Fig.1 shows the XRD patterns of bentonite and Ni/bentonite catalysts with different nickelcontents before H2reduction.The patterns showed obvious diffraction peaks at 2θ =19.9°and 35.0°,which corresponded to the(101)and(107)planes of montmorillonite(JCPDS card NO.29-1499).The diffraction peaks at 2θ =20.9°,and 26.6°corresponded to the(101)and(107)planes of SiO2(JCPDS card NO.46-1045).These findings indicated that the support was a typical bentonite[18].The diffraction peaks at 2θ =37.2°,43.3°,and 62.9°corresponded to the(111),(200)and(220)planes of cubic NiO(JCPDS card NO.47-1049),respectively,which indicated that NiO was formed after the nickel loading catalysts were calcined at 400°C for 4 h.However,the diffraction peaks of NiO were very weak in the 5 wt%and 10 wt%Ni/bentonite catalysts due to lesser amounts of Ni on bentonite.

Fig.1.XRDpatterns ofbentonite(a)and Ni/bentonite catalysts with 5 wt%(b),10 wt%(c),15 wt%(d),20 wt%(e),and 25 wt%(f)nickelcontent before H2 reduction.

On the basis of the data of line broadening at half the maximum intensity(fullwidth at half-maximum,FWHM)and the Bragg angle(θ),the Scherrerequation[19]was used to calculate the mean crystallite size of the NiO.The corresponding crystallite size metallic Ni was calculated by Eq.(1).Furthermore,the speci fic surface area SANi,crystallite size and dispersion of metallic Ni were calculated based on chemisorbed H2using Eqs.(2)–(4)and the results are listed in Table 1.

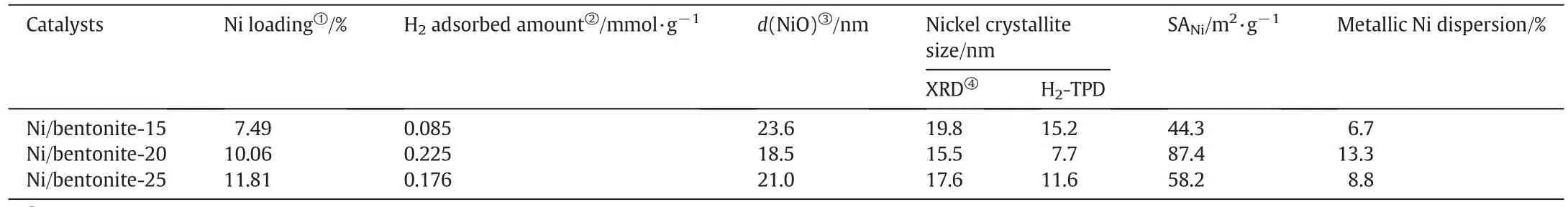

In Table 1,the average crystallite size of NiO on Ni/bentonite-15,Ni/bentonite-20,and Ni/bentonite-25 calculated by the Scherrer equation was 23.6,18.5,and 21.0 nm,respectively.The corresponding Nicrystallite size calculated by Eq.(1)was 19.8,15.5,and 17.6 nm,respectively.As comparison,the corresponding Nicrystallite sizes calculated based on chemisorbed H2using Eq.(4)was 15.2,7.7,and 11.6 nm,respectively.Therefore,the metallic Ni crystallite size calculated by both Eqs.(1)and(4)were accordant and the metallic Nicrystallite size on Ni/bentonite-20 was smaller than the other two catalysts.Furthermore,the metallic Nidispersion in the Ni/bentonite-20 catalyst was higher than that of the Ni/bentonite-15 and Ni/bentonite-25 catalysts.In general,metallic Niwas the active site in the nitrobenzene hydrogenation process[20],and the catalytic activity can be correlated with the dispersion and crystallite size ofmetallic Ni[21].Ithas been suggested thata homogeneous dispersion of NiOon the support would lead to a rich exposition ofmetallic Nion the surface ofbentonite,leading to more catalytic sites and a higher catalytic activity for the target reaction.Therefore,Ni/bentonite-20 should have a better catalytic performance on the nitrobenzene hydrogenation process for the higher dispersion and smaller crystallite size ofmetallic Ni.

3.2.Effectofnickelcontents on the catalytic hydrogenation ofnitrobenzene to aniline

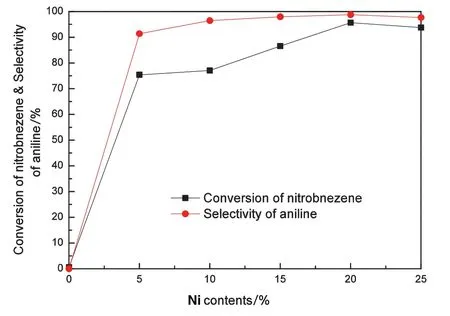

Fig.2 presents the results of the catalytic hydrogenation ofnitrobenzene to aniline over the Ni/bentonite catalysts with different nickel contents,which also shows bentonite as a comparison.When using bentonite as catalyst,aniline was not detected in the product.With the increase of the additive nickelcontents,the conversion ofnitrobenzene increased from 75.4%to 95.7%and then decreased to 93.8%;the selectivity ofaniline increased from 91.4%to 98.8%and then decreased to 97.7%.The conversion ofnitrobenzene and the selectivity of aniline both reached maximum values when the nickel content was 20 wt%,which were 95.7%and 98.8%,respectively.The main by-product confirmed by GC–MS was hydrazobenzene;however,the hydrazobenzene selectivity in the products was only 2%to 5%,which was very smalland can be ignored in the subsequent discussion.

According to the XRD patterns,the crystallite size of NiO(200)on the Ni/bentonite-20 catalyst calculated by the Scherrer equation was 18.5 nm,which was smaller than the crystallite size of NiO in the other catalysts.The catalytic activity was relevant to the crystallite size of Ni obtained from NiO after the reduction process.The calculated crystallite size and dispersion ofmetallic Niare listed in Table 1,andthe conversion of nitrobenzene and the selectivity of aniline were in accordance with these calculated data.Ni/bentonite-20 catalystwith a smaller crystallite size and higher dispersion of metallic Niexhibited a good catalytic performance,providing 95.7%conversion of nitrobenzene and 98.8%selectivity of aniline.Furthermore,the selectivity of aniline mightbe correlated to the support.The dispersion and crystallite size ofmetallic Niimpacted the selectivity ofaniline relatively.As seen in Fig.2,the selectivity ofaniline with different Ni/bentonite catalysts ranged from 96.5%to 98.8%when the nickelcontent was more than 10 wt%.This small fluctuation was probably caused by the dispersion and crystallite size ofmetallic Ni.

Table 1 The crystallite size,Nimetalsurface area,and the metallic Nidispersion in the Ni/bentonite catalysts

Fig.2.Effect of different nickel contents on the catalytic hydrogenation of nitrobenzene to aniline over Ni/bentonite catalysts.Reaction conditions:T=300°C,LHSV=4.8 ml·(g cat)-1·h-1,GHSV=4800 ml·(g cat)-1·h-1.

3.3.H2-TPR analysis ofcatalysts

Fig.3.H2-TPR pro files of the Ni/bentonite catalysts with 5 wt%,10 wt%,15 wt%,20 wt%,and 25 wt%nickelcontent.

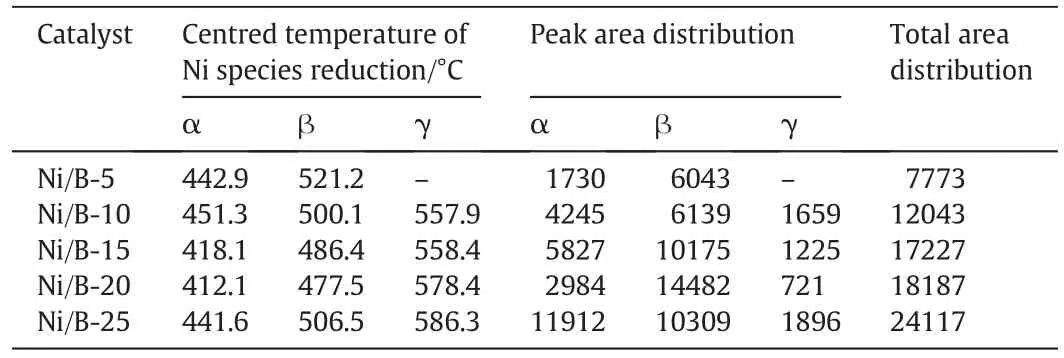

Nispecies is the main centre ofcatalytic activity for the hydrogenation process ofnitrobenzene and the reducibility of NiO species loaded on the support is highly affected by the metal-support interaction[22].A H2temperature programmed reduction(H2-TPR)analysis was made to evaluate the reducibility of the NiO species,the amount of Ni on the reduction of Nispecies,and the interaction between Niand bentonite.The results are shown in Fig.3 and Table 2.Generally,Ni2+is reduced to Ni0without going through intermediate oxides;therefore,H2consumption peaks appearing at different temperatures should be assigned to differentspecies[23].From Fig.3,only two Gaussian fitting peaks(peakαandβ)were found in the H2-TPR pro files of the Ni/bentonite-5 sample within the temperature range of100–650 °C,and three Gaussian fitting peaks(peak α,β,and γ)are shown in Fig.3 within the temperature range of 100–650 °C for the other catalysts.Peak α,which occurred in the temperature range of 413.2–436.2 °C(presented in Table 1),corresponded to the bulk NiO located on the external surface of the bentonite with a weak interaction with the bentonite[24],while peakβ,which occurred within the temperature range of478.9–515.5 °C,was caused by the reduction of NiOnanoparticles con fined within the mesoporous and thus had a relatively strong interaction with the bentonite[24–26].From Fig.3,with the increase of the loading amount of nickelfrom 5 wt%to 25 wt%,the amount of Ni species also increased,which was in accordance with other publications[27,28].As shown in Table 2,the totalreduced peak area increased with the Niloading amount of the catalyst from 5 wt%to 25 wt%,indicating the increase of the amount of nickel oxide.For the Ni/bentonite-20 catalyst,the reduction peaks ofαandβwere centred at 412.1°C and 477.5°C,respectively,which were lower than that of Ni/bentonite-5(442.9 °C,521.2 °C),Ni/bentonite-10(451.3 °C,500.1 °C),Ni/bentonite-15(418.1 °C,486.4 °C),and Ni/bentonite-25(441.6 °C,506.5°C),indicating the much higher dispersion of NiO on the surface ofbentonite for the Ni/bentonite-20 catalyst[29].The lower reducing temperature was bene ficial,which can avoid the formation of Nicrystal grains during the hydrogenation process,and more Nispecies can be exposed on the surface of the support,which can increase the reducibility of the catalyst.Out of all the Ni/bentonite catalysts,the lowest reduction temperatures of peakαand peakβwere observed when the nickelcontent was 20 wt%,suggesting that this catalyst exhibited an optimum reducing behaviour.Peakγ,presented in Fig.3 when the nickel content was more than 10 wt%and centred the temperature range of 558.1–591.7 °C,can be ascribed to smaller dispersed NiO particles,which had an intermediate interaction with the bentonite support[26].Peakδ,which occurred in allNi/bentonite catalystsamples at approximately 700°C,was relatively weak and can be attributed to the reduction of nickelaluminate or nickelsilicate[25,26].

The reduction temperatures of peakαand peakβin the Ni/bentonite-20 catalystwere centred at413.2 °C and 478.9 °C,respectively,and were lower than the corresponding reduction temperatures inthe other catalysts.This indicates the high dispersion of NiO on the surface ofbentonite[29],which may increase the catalytic activity of Ni/bentonite in the hydrogenation of nitrobenzene.Combined with the XRD results,both the smaller crystallite size of NiO and high dispersion of NiO on bentonite attributed to the optimalconversion of nitrobenzene and selectivity ofaniline.

Table 2 Temperatures and area distributions of reduction peaks of Ni/bentonite catalysts with different nickelcontents①

3.4.XPS analysis

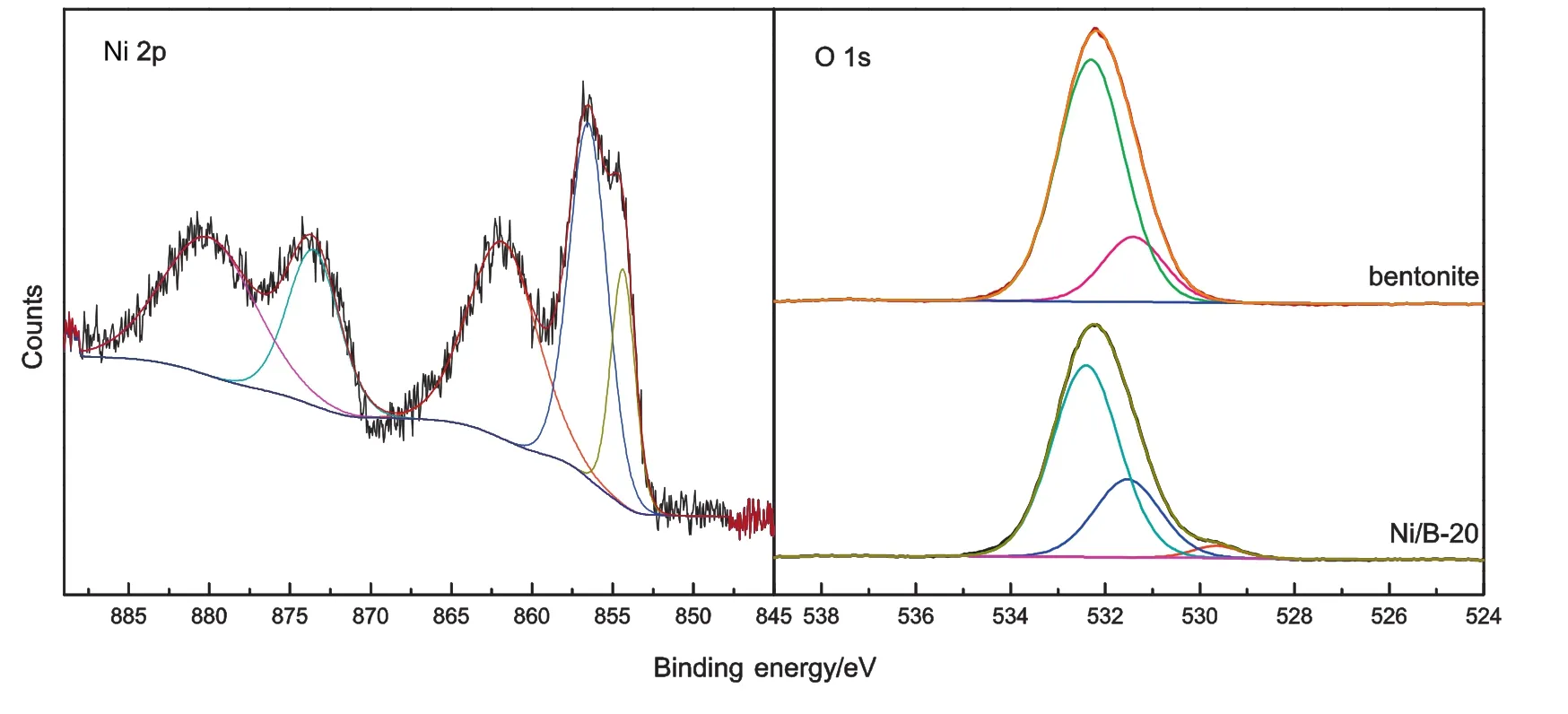

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy(XPS)was utilized to study the oxidation states of the elements on the surfaces of the bentonite and Ni/bentonite-20 catalysts;the results are shown in Fig.4.The binding energies ofapproximately 854.4 eV(Ni2p3/2)and 873.6 eV(Ni2p1/2)can be ascribed to Ni2+in NiO[30,31],and the binding energy of approximately 856.5 eV was caused by nickel aluminate[28,32,33].The binding energies of approximately 861.8 eV and 880.0 eV corresponded to the strong shake-up process of Ni2p3/2and Ni2p1/2,respectively,in NiO[31,33,34].The O 1s peaks in Fig.4 can be fitted to three sub-peaks centred at 532.2 eV,531.2 eV,and 529.6 eV,which corresponded to the three types of O on SiO2[35],Al2O3[36],and NiO[34,37],respectively.Compared to bentonite,there were decreases of 0.2 eV and 0.4 eV in the binding energies of Gaussian fitting peaks centred at 532.2 eV and 531.2 eV and attributed to the O in SiO2and Al2O3,respectively,in the Ni/bentonite-20 catalyst,which indicated that there was a strong interaction between the metaland bentonite after the metals were loaded into the support[38].

3.5.Catalytic hydrogenation ofnitrobenzene to aniline on Ni/bentonite catalysts

3.5.1.Effectofreduction temperature

Reduction temperature is an importantparameter,and the effects of the reduction temperature on the nitrobenzene hydrogenation to aniline were studied from 350 to 550°C.The results are shown in Fig.5.

According to Fig.5,when the reduction temperatures were 350,400,450,500,and 550°C,the nitrobenzene conversions were 87.5%,95.7%,96.4%,96.2%,and 94.6%,respectively.The conversion of nitrobenzene first increased with the increase of reduction temperature;then,it remained stable,and the change in the selectivity ofaniline was within 3%as the reduction temperatures changed,indicating thatthe reduction temperature had slight impacts on the aniline selectivity.Metallic Ni was the active site in the nitrobenzene hydrogenation reaction[19],and the crystallite size ofmetallic Niwas related to the crystallite size ofNiO after the reduction process,which suggesting thatenough metallic Niactive sites were obtained for nitrobenzene hydrogenation after reduction at 400 °C.Therefore,400 °C was chosen as the optimal reduction temperature for this hydrogenation process.

3.5.2.Effect ofnitrobenzene space velocity

The Ni/bentonite-20 catalyst was utilized in aniline synthesis from nitrobenzene with various nitrobenzene liquid space velocities(LHSV)from 2.4–7.2 ml·(g cat)-1·h-1,to investigate the effects of LHSV on the synthetic process.The results are presented in Fig.6.With the increase of LHSV from 2.4 to 7.2 ml·(g cat)-1·h-1,the conversion of nitrobenzene decreased from 99.9%to 57.2%,and the selectivity of aniline decreased from 99.2%to 88.2%.The increase of LHSV probably shortened the contact time between the surface of the catalyst and the nitrobenzene/H2mixing gases,thus leading to insuf ficient contact between the nitrobenzene/H2gases.Although the conversion ofnitrobenzene and the selectivity ofaniline decreased,2.4 ml·(g cat)-1·h-1was chosen as the optimal space velocity for the high conversion of nitrobenzene and selectivity of aniline.4.8 ml·(g cat)-1·h-1was chosen for the other reactions to provide a comparison of the data.

Fig.4.XPS spectra of Ni2p and O 1s regions for bentonite and Ni/bentonite-20 catalyst.

Fig.5.Effect of the reduction temperature on the conversion of nitrobenzene and selectivity of aniline over Ni/bentonite-20.Reaction conditions:T=300°C,LHSV=4.8 ml·(g cat)-1·h-1,GHSV=4800 ml·(g cat)-1·h-1.

Fig.6.Effect ofnitrobenzene liquid space velocity(LHSV)on the catalytic hydrogenation of nitrobenzene to aniline over Ni/bentonite-20.Reaction conditions:T=300°C,LHSV=2.4–7.2 ml·(g cat)-1·h-1,GHSV=4800 ml·(g cat)-1·h-1.

3.5.3.EffectofH2space velocity

The Ni/bentonite-20 catalyst was utilized in aniline synthesis from nitrobenzene with various H2gaseous space velocities(GHSV)from 1200–6000 ml·(g cat)-1·h-1to investigate the effects of GHSV on the hydrogenation process.The results are shown in Fig.7.With the increase of GHSV from 1200 to 6000 ml·(g cat)-1·h-1,the conversion of nitrobenzene increased from 23.6%to 98.9%,and the selectivity of aniline changed slightly.The increase of GHSV provided enough hydrogen sources for the hydrogenation reaction,leading to a higher conversion of nitrobenzene.Although the conversion of nitrobenzene was not the highest when the GHSV was 4800 ml·(g cat)-1·h-1,this value was chosen as the optimal GHSV considering the comparable data and the economics ofreaction.

3.5.4.Stability ofNi/bentonite catalyst

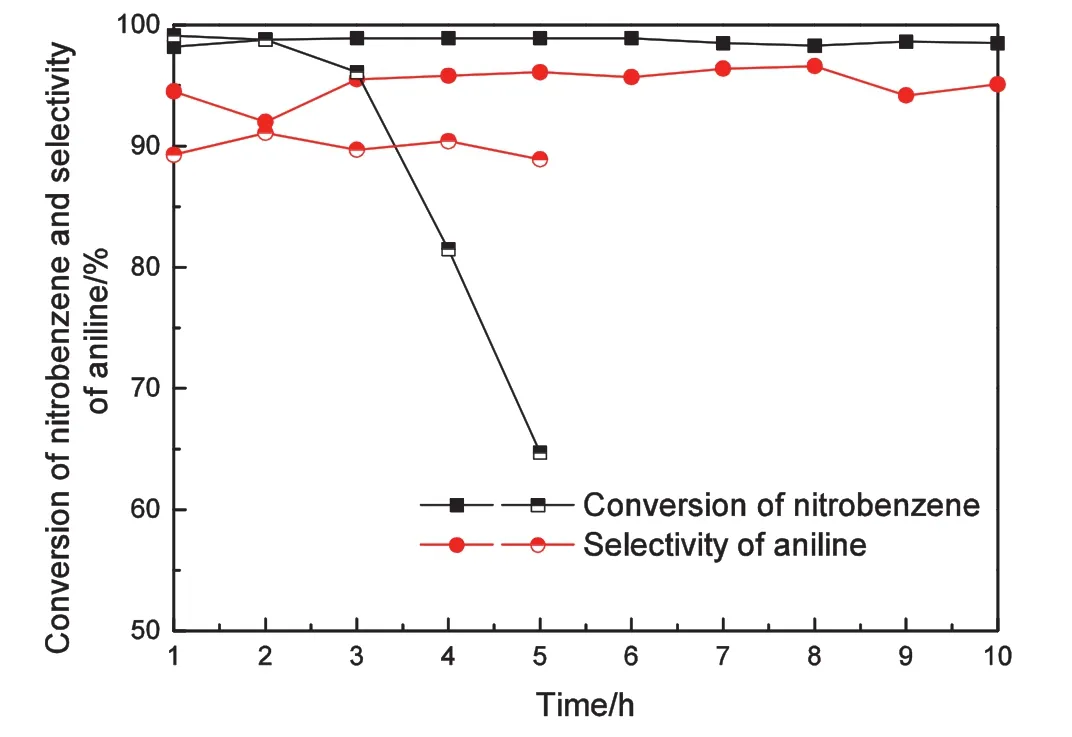

The stability of the Ni/bentonite-20 catalyst was studied in the aniline synthesis via nitrobenzene/H2at 300°C with GHSV=4800 ml·(g cat)-1·h-1and LHSV=4.8 ml·(g cat)-1·h-1,and a Ni/γ-Al2O3-20 catalyst was used as a comparison.The results are shown in Fig.8.

Fig.7.Effect of gaseous H2 space velocity(GHSV)on the catalytic hydrogenation of nitrobenzene to aniline over Ni/bentonite-20.Reaction conditions:T=300°C,LHSV=4.8 ml·(g cat)-1·h-1,GHSV=1200–6000 ml·(g cat)-1·h-1.

Fig.8.Conversion ofnitrobenzene and selectivity of aniline over Ni/bentonite-20(solid)and Ni/γ–Al2O3–20(half-solid)catalysts with time on stream.Reaction conditions:T=300 °C,LHSV=4.8 ml·(g cat)-1·h-1,GHSV=4800 ml·(g cat)-1·h-1.

As a comparison,the Ni/γ–Al2O3–20 catalyst deactivated quickly,and the conversion of nitrobenzene decreased from 99.2%to 64.7%during the 5 h reaction process.Moreover,the selectivity of aniline was approximately 90%.For the Ni/bentonite-20 catalyst,the selectivity ofaniline and the conversion ofnitrobenzene remained almostconstant during the whole reaction process,which indicated that the Ni/bentonite-20 was a stable catalystfor the nitrobenzene catalytic hydrogenation to aniline,producing an aniline selectivity of approximately 95.0%and a nitrobenzene conversion ofapproximately 98.0%after 10 h.

4.Conclusions

Ni/bentonite catalysts were prepared with different nickelcontents and were used for the hydrogenation of nitrobenzene to synthesize aniline.Compared to other Ni/bentonite catalysts,Ni/bentonite-20 exhibited better catalytic properties in the hydrogenation process,producing 95.7%conversion of nitrobenzene and 98.8%selectivity of aniline.Both the smallcrystallite size of NiO and the high dispersion of NiO contributed to the conversion ofnitrobenzene and selectivity of aniline.The catalytic stability of the Ni/bentonite-20 catalyst was very high when the LHSV was 4.8 ml·(g cat)-1·h-1.

[1]M.Kulkarni,A.Chaudhari,Microbialremediation ofnitro-aromatic compounds:An overview,J.Environ.Manag.85(2007)496–512.

[2]L.Fu,W.Cai,A.Wang,Y.Zheng,Photocatalytic hydrogenation of nitrobenzene to aniline over tungsten oxide-silver nanowires,Mater.Lett.142(2015)201–203.

[3]M.M.Dell’Anna,S.Intini,G.Romanazzi,A.Rizzuti,C.Leonelli,F.Piccinni,P.Mastrorilli,Polymer supported palladium nanocrystals as ef ficient and recyclable catalyst for the reduction of nitroarenes to anilines under mild conditions in water,J.Mol.Catal.A Chem.395(2014)307–314.

[4]X.Fang,S.Yao,Z.Qing,F.Li,Study on silica supported Cu–Cr–Mo nitrobenzene hydrogenation catalysts,Appl.Catal.A 161(1997)129–135.

[5]V.Mohan,C.V.Pramod,M.Suresh,K.H.Prasad Reddy,B.D.Raju,K.S.Rama Rao,Advantage of Ni/SBA-15 catalyst over Ni/MgO catalyst in terms of catalyst stability due to release of water during nitrobenzene hydrogenation to aniline,Catal.Commun.18(2012)89–92.

[6]M.Turáková,M.Králik,P.Lehocký,Ľ.Pikna,M.Smrčová,D.Remeteiová,A.Hudák,In fluence of preparation method and palladium content on Pd/C catalysts activity in the liquid phase hydrogenation of nitrobenzene to aniline,Appl.Catal.A 476(2014)103–112.

[7]N.John Jebarathinam,M.Eswaramoorthy,V.Krishnasamy,G.M.Dhar,Hydrogenation of nitrobenzene over copper containing spinels,in:T.S.R.P.Rao(Ed.),Studies in Surface Science and Catalysis,Elsevier 1998,pp.1039–1043.

[8]H.Blaser,U.Siegrist,H.Steiner,M.Studer,R.Sheldon,H.van Bekkum,Fine Chemicals Through Heterogeneous Catalysis,Wiley/VCH,Weinheim,2001 389.

[9]S.Jeenpadiphat,D.N.Tungasmita,Esteri fication of oleic acid and high acid content palm oilover an acid-activated bentonite catalyst,Appl.Clay Sci.87(2014)272–277.

[10]M.E.Sedaghat,M.Rajabpour Booshehri,M.R.Nazarifar,F.Farhadi,Surfactant modified bentonite(CTMAB-bentonite)as a solid heterogeneous catalyst for the rapid synthesis of 3,4-dihydropyrano[c]chromene derivatives,Appl.Clay Sci.95(2014)55–59.

[11]F.Tomul,Adsorption and catalytic properties of Fe/Cr-pillared bentonites,Chem.Eng.J.185–186(2012)380–390.

[12]H.Xu,T.Yu,J.Liu,Photo-degradation of Acid Yellow 11 in aqueous on nano-ZnO/Bentonite under ultraviolet and visible light irradiation,Mater.Lett.117(2014)263–265.

[13]Z.Liu,Z.Qin,J.Zhang,Y.Wang,Hydrogenation of nitrobenzene to aniline on amorphous Ni–Mo–P catalysts and mechanism ofcatalystdeactivation,CIESC J.63(2012)121–126.

[14]Y.Jiang,R.Liu,Z.Qin,H.Ji,X.Deng,Intrinsic kinetics of catalytic hydrogenation of nitrobenzene to aniline on Ni–P amorphous alloy catalyst,Ind.Catal.22(2014)93–99.

[15]Z.Qin,Z.Liu,Y.Wang,Promotion effect of Mo on amorphous Ni–P catalyst for liquid-phase nitrobenzene catalytic hydrogenation to aniline,Chem.Eng.Commun.201(2014)338–351.

[16]J.Xu,L.Chen,K.F.Tan,A.Borgna,Effect of boron on the stability of Ni catalysts during steam methane reforming,J.Catal.261(2009)158–165.

[17]S.Velu,S.K.Gangwal,Synthesis of alumina supported nickelnanoparticle catalysts and evaluation ofnickelmetaldispersions by temperature programmed desorption,Solid State Ionics 177(2006)803–811.

[18]Z.Liu,A.U.Md,Z.Sun,FT-IR and XRD analysis of natural Na-bentonite and Cu(II)-loaded Na-bentonite,Spectrochim.Acta A 79(2011)1013–1016.

[19]G.Grancini,S.Marras,M.Prato,C.Giannini,C.Quarti,F.De Angelis,M.De Bastiani,G.E.Eperon,H.J.Snaith,L.Manna,A.Petrozza,The impact of the crystallization processes on the structural and optical properties of hybrid perovskite films for photovoltaics,J.Phys.Chem.Lett.5(2014)3836–3842.

[20]A.Mahata,R.K.Rai,I.Choudhuri,S.K.Singh,B.Pathak,Directvs.indirectpathway for nitrobenzene reduction reaction on a Nicatalyst surface:a density functionalstudy,Phys.Chem.Chem.Phys.16(2014)26365–26374.

[21]M.Varkolu,V.Velpula,R.Pochamoni,A.R.Muppala,D.R.Burri,S.R.R.Kamaraju,Nitrobenzene hydrogenation over Ni/TiO2catalyst in vapour phase at atmospheric pressure:in fluence of preparation method,Appl.Petrochem.Res.(2015)1–9.

[22]K.Tao,L.Shi,Q.Ma,D.wang,C.Zeng,C.Kong,M.Wu,L.Chen,S.Zhou,Y.Hu,N.Tsubaki,Methane reforming with carbon dioxide over mesoporous nickel–alumina composite catalyst,Chem.Eng.J.221(2013)25–31.

[23]C.Louis,Z.X.Cheng,M.Che,Characterization of nickel/silica catalysts during impregnation and further thermal activation treatment leading to metal particles,J.Phys.Chem.97(1993)5703–5712.

[24]D.Li,L.Zeng,X.Li,X.Wang,H.Ma,S.Assabumrungrat,J.Gong,Ceria-promoted Ni/SBA-15 catalysts for ethanolsteam reforming with enhanced activity and resistance to deactivation,Appl.Catal.B 176–177(2015)532–541.

[25]X.Lu,F.Gu,Q.Liu,J.Gao,Y.Liu,H.Li,L.Jia,G.Xu,Z.Zhong,F.Su,VOxpromoted Ni catalysts supported on the modi fied bentonite for CO and CO2methanation,Fuel Process.Technol.135(2015)34–46.

[26]B.Mile,D.Stirling,M.A.Zammitt,A.Lovell,M.Webb,TPR studies of the effects of preparation conditions on supported nickel catalysts,J.Mol.Catal.62(1990)179–198.

[27]H.Lu,H.Yin,Y.Liu,T.Jiang,L.Yu,In fluence of support on catalytic activity of Ni catalysts in p-nitrophenol hydrogenation to p-aminophenol,Catal.Commun.10(2008)313–316.

[28]R.Yang,X.Li,J.Wu,X.Zhang,Z.Zhang,Y.Cheng,J.Guo,Hydrotreating of crude 2-ethylhexanolover Ni/Al2O3catalysts:Surface Ni species-catalytic activity correlation,Appl.Catal.A 368(2009)105–112.

[29]C.-W.Hu,J.Yao,H.-Q.Yang,Y.Chen,A.-M.Tian,On the inhomogeneity oflow nickel loading methanation catalyst,J.Catal.166(1997)1–7.

[30]J.Gao,C.Jia,J.Li,F.Gu,G.Xu,Z.Zhong,F.Su,Nickelcatalysts supported on barium hexaaluminate for enhanced CO methanation,Ind.Eng.Chem.Res.51(2012)10345–10353.

[31]N.K.Shrestha,M.Yang,Y.C.Nah,I.Paramasivam,P.Schmuki,Self-organized TiO2nanotubes:visible light activation by Nioxide nanoparticle decoration,Electrochem.Commun.12(2010)254–257.

[32]Y.Bang,S.Park,S.J.Han,J.Yoo,J.H.Song,J.H.Choi,K.H.Kang,I.K.Song,Hydrogen production by steam reforming of lique fied natural gas(LNG)over mesoporous Ni/Al2O3catalyst prepared by an EDTA-assisted impregnation method,Appl.Catal.B 180(2016)179–188.

[33]S.Natesakhawat,R.B.Watson,X.Wang,U.S.Ozkan,Deactivation characteristics of lanthanide-promoted sol–gel Ni/Al2O3catalysts in propane steam reforming,J.Catal.234(2005)496–508.

[34]V.V.Kaichev,A.Y.Gladky,I.P.Prosvirin,A.A.Saraev,M.Hävecker,A.Knop-Gericke,R.Schlögl,V.I.Bukhtiyarov,In situ XPS study of self-sustained oscillations in catalytic oxidation of propane over nickel,Surf.Sci.609(2013)113–118.

[35]T.L.Barr,The nature of the relative bonding chemistry in zeolites:An XPS study,Zeolites 10(1990)760–765.

[36]B.Dzhurinskii,D.Gati,N.Sergushin,V.Nefedov,Y.V.Salyn,Simple and coordination compounds.An X-ray photoelectron spectroscopic study of certain oxides,Russ.J.Inorg.Chem.20(1975)2307–2314.

[37]P.Marcus,J.M.Grimal,The anodic dissolution and passivation of NiCrFe alloys studied by ESCA,Corros.Sci.33(1992)805–814.

[38]E.Dündar-Tekkaya,Y.Yürüm,Effect of loading bimetallic mixture of Ni and Pd on hydrogen storage capacity of MCM-41,Int.J.Hydrog.Energy 40(2015)7636–7643.

Chinese Journal of Chemical Engineering2016年9期

Chinese Journal of Chemical Engineering2016年9期

- Chinese Journal of Chemical Engineering的其它文章

- In situ synthesis ofhydrophobic magnesium hydroxide nanoparticles in a novelimpinging stream-rotating packed bed reactor☆

- Enhancing the hydration reactivity ofhemi-hydrate phosphogypsum through a morphology-controlled preparation technology☆

- Synthesis and characterization ofcopolymers ofpoly(m-xylylene adipamide)and poly(ethylene terephthalate)oligomers by melt copolycondensation

- Improvement of CO2 capture performance ofcalcium-based absorbent modi fied with palygorskite☆

- Adsorption behavior ofcarbon dioxide and methane in bituminous coal:A molecular simulation study☆

- Characterization of the adsorption behavior ofaqueous cadmium on nanozero-valent iron based on orthogonalexperiment and surface complexation modeling☆