Prevalence of refractive errors among primary school children in a tropical area, Southeastern Iran

Monireh Mahjoob, Samira Heydarian*, Jalil Nejati, Alireza Ansari-Moghaddam, Nahid RavandehDepartment of Optometry, School of Paramedical Science, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, IranHealth Promotion Research Center, Zahedan University of Medical Sciences, Zahedan, Iran

Prevalence of refractive errors among primary school children in a tropical area, Southeastern Iran

Monireh Mahjoob1, Samira Heydarian1*, Jalil Nejati2, Alireza Ansari-Moghaddam2, Nahid Ravandeh21Department of Optometry, School of Paramedical Science, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran

2Health Promotion Research Center, Zahedan University of Medical Sciences, Zahedan, Iran

Management and decision-making http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.apjtb.2015.10.008

Tel: +98 9113547406

E-mail: opt_heydarian@yahoo.com

The study protocol was performed according to the Helsinki declaration and approved by Ethical Committee of Zahedan University of Medical Sciences. Informed written consent was obtained from the parents/legal guardians after a detailed explanation of the study.

Peer review under responsibility of Hainan Medical University. The journal implements double-blind peer review practiced by specially invited international editorial board members.

Foundation Project: Supported by Zahedan University of Medical Sciences (Grant No. 91-506).

2221-1691/Copyright©2016 Hainan Medical University. Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

ARTICLE INFO

Article history:

Received 1 Sep 2015

Receivedinrevisedform16 Sep2015

Accepted 5 Oct 2015

Available online 10 Dec 2015

Keywords:

Refractive error

Myopia

Hyperopia

Astigmatism

Anisometropia

ABSTRACT

Objective: To determine the prevalence of refractive errors among primary school children in Zahedan District, Southeastern Iran, as a tropical area.

Methods: In this cross sectional study, a total of 400 students were selected randomly using multi-stage sampling technique. Myopia was defined as spherical equivalent (SE) of−0.5 diopter (D) or more, hyperopia was defined as SE of +2.00 D or more and a cylinder refraction greater than 0.75 D was considered astigmatism. Anisometropia was defined as a difference of 1 D or more between two eyes. Cycloplegic refractive status was measured using auto-refractometer (Topcon 8800). Data were analyzed using SPSS, version 22 software program.

Results: Mean±SD of SE was (1.71±1.16) D. A total of 20 students [6.3%, 95% confidence interval (CI): 3.96%–9.64%] were myopic (≤−0.5 D), 186 students (58.1%, 95% CI: 52.50%–63.56%) were hyperopic (≥+2.00 D) and 114 students (35.6%, 95% CI: 30.43%–41.18%) were emmetropic. The prevalence of astigmatism (≥0.75 D) among students was 3.4% (95% CI: 1.82%–6.25%). Anisometropia of 1 D or more was found in 21.3% (95% CI: 16.98%–26.23%) of the studied population. The prevalence of refractive errors was higher among girls than boys (73.1% vs. 55.6%, P = 0.001), but it was not significantly different among different age groups (P = 0.790).

Conclusions: Refractive errors affect a sizable portion of students in Zahedan. Although myopia is not very prevalent, the high rate of hyperopia in the studied population emphasizes its need for attention.

1. Introduction

Refractive errors affect a large proportion of world's population, regardless of sex, age and ethnic group[1]. We can easily diagnose, measure and correct these refractive errors with spectacles or other refractive corrections to achieve normal vision. If, however, refractive errors are not corrected or the correction be inappropriate, they may become a major cause of visual impairment and even blindness [2]. The estimate of visual disability due to uncorrected refractive errors is a public health concern. It is reported that more than 12 million children in the age group 5–15 years are visually impaired due to uncorrected or inadequately corrected refractive errors [3].

Refractive errors can impose a heavy financial burden on the society [4]. School children are considered a high risk group because uncorrected refractive errors can negatively affect their learning abilities and their mental and physical health[5,6].

To address the issue of visual impairment in children, the World Health Organization recently launched a global initiative, VISION 2020-The Right to Sight. Their strategy for the elimination of avoidable visual disability and blindness includes the correction of refractive errors[7]. So, in order to provide an early detection and initiate early treatment, a professional based screening program for all school-aged children is recommended. In recent years, a number of surveys have been done among students and elderly subjects in Iran[8–14]. These studiessuggest that the prevalence of hyperopia in Iran is high, so further studies in different parts of the country should be done to determine the role of factors such as race, genetics and even environment.

The objective of this study was to determine the prevalence and pattern of refractive errors among primary school children in the age group of 7–12 years of both sexes in Zahedan District, Southeastern Iran.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study area

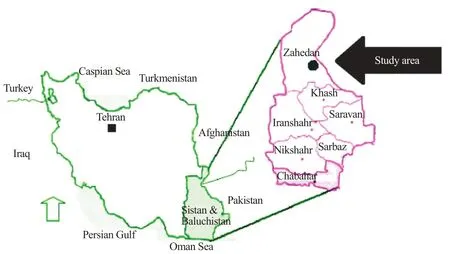

This cross sectional study was carried out among primary school children of Zahedan District in 2012. Zahedan is the capital of Sistan and Baluchestan Province, located in south east of Iran and known as a tropical area (Figure 1) [15].

2.2. Optometric research

We conducted this study based on Refractive Error Study in Children protocol [5]. To maintain the comparability of our results with other studies, consistent definitions for refractive errors were used. However, there were some differences in methods. One of these differences was that the target population in our study was school children who greatly affected the generalizability of the results, because it failed to cover school age children who not attended school. However, it seemed that in Zahedan, the majority of primary school-age children were in school. The other difference was that our sample was drawn from children between 7 and 12 years, rather than 5–15 years of age.

Figure 1. Map of Sistan–Baluchestan Province, located in Zahedan District, Southeastern Iran[16].

The sample size was calculated using a single proportion formula. Assuming an estimated refractive error prevalence rate of 24.6%, a precision of 0.05 diopter (D) and 95% confidence interval (CI) (Z1-α/2 = 1.96), the total sample size was calculated as 288 students [8]. Due to the possibility of loss of samples, we increased the sample size to 400 students. The multi-stage sampling technique was used to select random samples of school children. Zahedan has two administrative districts. In each district, schools were listed according to public and private ownership. Four private and four public schools were randomly selected (2 boys' centers and 2 girls' centers, from each group). Lists of Grade 1 to Grade 5 students from each selected school were obtained and then random selection of the students was carried out by using a simple table of randomization. A total of 25 students were selected from each school, based on their academic grade. A total of 400 students were selected, among which 320 students (80%) participated in the study, including 160 boys and 160 girls with age ranging from 7 to 12 years.

The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of Zahedan University of Medical Sciences. Our study was conducted according to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed written consent was obtained from the parents/legal guardians after a detailed explanation of the study. Assents from selected school children were also obtained. After acquiring their consent, they completed a questionnaire on personal information and family history. Students who refused visual acuity assessment or eye examination and with any previous ocular surgery or ocular pathology including any strabismus, corneal opacity, cataract and retinal pathology which were recognized in initial ophthalmic examination, were excluded from the study.

Those students included in the study underwent a complete initial ophthalmic examination. Slit lamp biomicroscopy (Model BQ 900: Haag Streit, Bern, Switzerland) and ophthalmoscopy (Ophthalmoscope, Heine Beta 200, Germany) were done for all thestudents.Then,anoptometristbeganoptometricexaminations with testing visual acuity at 6 m in good lighting conditions using Snellen eye chart for each eye separately, according to standard protocol. Cycloplegic refractive status was measured for all the participantsusingauto-refractometer (Topcon8800),45minafter instilling 2 drops of 1% cyclopentolate with 5 min apart.

Spherical equivalent (SE) was used for calculations of refractive error. The SE was derived by adding the spherical component of refraction to half of the cylindrical component. Myopia was defined as an SE of at least−0.5 D and hyperopia was defined as an SE of +2.00 D or more. Emmetropia was defined if neither eye was myopic or hyperopic. Astigmatic students were a cylinder refraction of 0.75 D or more in at least one eye, which was recorded with a negative sign. Anisometropia was defined as a difference in SE of at least 1.0 D between right and left eyes. As SEs in the right and left eyes were highly correlated (Spearman correlation: r = 0.719, P = 0.000), we presented data for only the right eye.

Data were analyzed using SPSS, version 22 software program. Percentage and 95% CI were used to describe the prevalence of refractive errors. Spearman Chi-squared test was applied for qualitative data. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

Of the 400 primary school children approximately, 320 were included with approved consent forms from their parents/ guardians with a response rate of 80%, from which 50% were girl and 50% were boy. The age of the included school children ranged from 7 to 12 years with a mean±SD of (9.11±1.62) years and there was no significant differences between the mean±SD age of girls (9.06±1.59) and boys (9.16±1.64) (P = 0.606).

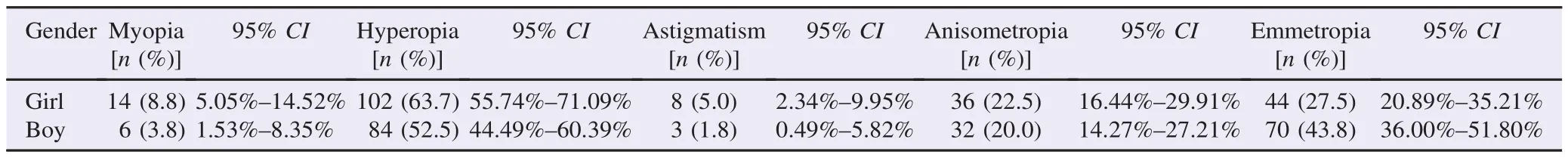

Mean±SD of SE was 1.71±1.16 ranged from−2.5 to +8 D overall, 1.68±1.19 ranged from−2.25 to +8 D in boys and 1.75±1.13 ranged from−2.5 to +4 D in girls (P = 0.181). The overall prevalence of refractive errors among school children was 64.4% (95% CI: 58.83%–69.58%), higher among girls than boys (73.1% vs. 55.6%, P = 0.001), but it was not significantly different among different age groups (P = 0.790). Tables 1 and 2 show the prevalence of different types of refractive errors basedon sex and age. As these tables shown, 20 students (6.3%, 95% CI: 3.96%–9.64%) were myopic (≤−0.5 D), 186 students (58.1%, 95% CI: 52.50%–63.56%) were hyperopic (≥+2.00 D), and 114 (35.6%, 95% CI: 30.43%–41.18%) were emmetropic.

Table 1Prevalence of different types of refractive errors based on age.

Table 2Prevalence of different types of refractive errors based on sex.

Mean±SD of cylindrical power was (−0.045±0.280) D. The prevalence of astigmatism (≥0.75 D) among students was 3.4% (95% CI: 1.82%–6.25%), from which 70% (95% CI: 35.37%–91.91%) was the rule astigmatism and 30% (95% CI: 8.09%–64.63%) was oblique astigmatism. There was no sex and also age difference with regard to the prevalence of astigmatism (P = 0.056, P = 0.486, respectively).

Anisometropia of 1 D or more was found in 21.3% (95% CI: 16.98%–26.23%) of the studied population and the differences between girls and boys (P = 0.585), and different age groups (P = 0.902) were not significant.

4. Discussion

The prevalence of different types of refractive errors among school children has already been evaluated in various studies during the past years [8–11,17,18]. In any discussion of the prevalence of refractive errors, we must consider that the prevalence varies widely from one geographical, racial or occupational group to another. Factors such as types of studied populations, different definitions, and methods of measurement (cycloplegia or non-cycloplegia), patient's age and ethnic differences could be responsible for these differences.

In this cross sectional study, we assessed the prevalence of refractive errors among primary school children in Zahedan. Several surveys with a similar methodology have been performed in different part of Iran. In 2002, the prevalence of different types of refractive errors in those younger than 15 years of age was studied in Tehran, which reported that the prevalence of myopia and hyperopia based on cycloplegic refraction was 7.2% and 76.2%, respectively[19]. In 2006–2007, a similar study was carried out in Mashhad and their results showed that the prevalence of myopia and hyperopia was 2.4%, and 87.9%, respectively [10]. Rezvan et al. evaluated the prevalence of refractive errors among school children in Northeastern Iran and reported that the prevalence of hyperopia in Northeastern Iran was higher than that of some countries [8]. In consistent to other reports from Iran, the prevalence of hyperopia in our study was higher than myopia [8–11].

The prevalence of astigmatism has varied in different studies in different populations. In the current study, we have found a low prevalence of astigmatism (3.4%) and a result was lower than that reported by other studies[8–11]. We know that the racerelated factors are among the reasons of the difference in the prevalence of astigmatism worldwide[20,21]. However, similar to other studies, our results showed that the prevalence of astigmatism did not change significantly with age, but withthe-rule astigmatism was more prevalent than against-the-rule or oblique astigmatism. The high prevalence of with-the-rule astigmatism in primary school children confirms the effect of age on astigmatism axis [22–24].

The prevalence of anisometropia according to a cut-point of 1 D or higher is different in school age populations. In our study, anisometropia was found in 21.3% of the students which was higher than previous studies [9–12]. However, since anisometropia may disturb binocular vision, its correction particularly in younger subjects is very important.

We also found higher prevalence of refractive errors among girls compared to boys, which confirms the results of previous studies in Iran [10–12]. Similar findings were also reported from Saudi Arabia, Qatar, India and Ghana [16,25–27]. Moreover, some studies have demonstrated an equal prevalence among two sex groups [8–11,28].

In this study, no association was found between ageandrefractiveerrors,thoughotherstudiesstatedotherwiseand a difference may be attributed to the 5 year of age range[11,22–24].

This study was conducted to provide baseline data on the prevalence rate of refractive errors among primary school children in Zahedan, Iran. Based on the results of the study, refractive errors affected a fairly large portion of students in this area. Primary school education is the most critical educational years since children achieve basic literacy and numeracy during this period. Becauseofthe importanceofgoodvisual acuityinthisagegroup, the health system should give priority to identifying affected students and correcting their refractive errors. Periodic screening in schools should be performed, and teachers and their parents should be educated about the effects of uncorrected refractive errors on the learning abilities and development of children.

Conflict of interest statement

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This article is a part of the results of the fifth author's thesis for achievement of BSc degree in Optometry from Zahedan University of Medical Sciences, Iran. The authors wish to thank the staff of primary schools of Zahedan District for their cooperation. This study was financially supported by Zahedan University of Medical Sciences (Grant No. 91–506).

References

[1] Pascolini D, Mariotti SP. Global estimates of visual impairment: 2010. Br J Ophthalmol 2012; 96(5): 614-8.

[2] Abdullah AS, Jadoon MZ, Akram M, Awan ZH, Azam M, Safdar M, et al. Prevalence of uncorrected refractive errors in adults aged 30 years and above in a rural population in Pakistan. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad 2015; 27(1): 8-12.

[3] Gore FM, Bloem PJ, Patton GC, Ferguson J, Joseph V, Coffey C, et al. Global burden of disease in young people aged 10–24 years: a systematic analysis. Lancet 2011; 377(9783): 2093-102.

[4] Roberts CB, Hiratsuka Y, Yamada M, Pezzullo ML, Yates K, Takano S, et al. Economic cost of visual impairment in Japan. Arch Ophthalmol 2010; 128(6): 766-71.

[5] Negrel AD, Maul E, Pokharel GP, Zhao J, Ellwein LB. Refractive error study in children: sampling and measurement methods for a multi-country survey. Am J Ophthalmol 2000; 129: 421-6.

[6] Gilbert C, Foster A. Childhood blindness in the context of VISION 2020-the right to sight. Bull World Health Organ 2001; 79(3): 227-32.

[7] International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness. VISION 2020–the right to sight. London: International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness. [Online] Available from: http://www. vision2020.org/main.cfm [Accessed on 20th August, 2015]

[8] Rezvan F, Khabazkhoob M, Fotouhi A, Hashemi H, Ostadimoghaddam H, Heravian J, et al. Prevalence of refractive errors among school children in Northeastern Iran. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt 2012; 32(1): 25-30.

[9] Yekta A, Fotouhi A, Hashemi H, Dehghani C, Ostadimoghaddam H, Heravian J, et al. Prevalence of refractive errors among schoolchildren in Shiraz, Iran. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2010; 38(3): 242-8.

[10] Ostadi-Moghaddam H, Fotouhi A, Khabazkhoob M, Heravian J, Yekta AA. Prevalence and risk factors of refractive errors among schoolchildren in Mashhad, 2006–2007. Iran J Ophthalmol 2008; 20(3): 3-9.

[11] Fotouhi A, Hashemi H, Khabazkhoob M, Mohammad K. The prevalence of refractive errors among schoolchildren in Dezful, Iran. Br J Ophthalmol 2007; 91(3): 287-92.

[12] Ostadimoghaddam H, Fotouhi A, Hashemi H, Yekta A, Heravian J, Rezvan F, et al. Prevalence of the refractive errors by age and gender: the Mashhad eye study of Iran. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2011; 39(8): 743-51.

[13] Yekta A, Hashemi H, Ostadimoghaddam H, Shafaee S, Norouzirad R, Khabazkhoob M. Prevalence of refractive errors among the elderly population of Sari, Iran. Iran J Ophthalmol 2013; 25(2): 123-32.

[14] Yekta AA, Fotouhi A, Khabazkhoob M, Hashemi H, Ostadimoghaddam H, Heravian J, et al. The prevalence of refractive errors and its determinants in the elderly population of Mashhad, Iran. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2009; 16(3): 198-203.

[15] Nejati J, Vatandoost H, Oshghi MA, Salehi M, Mozafari E, Moosa-Kazemi SH. Some ecological attributes of malarial vector Anopheles superpictus Grassi in endemic foci in Southeastern Iran. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed 2013; 3(12): 1003-8.

[16] Ovenseri-Ogbomo GO, Assien R. Refractive error in school children in Agona Swedru, Ghana. South Afr Optom 2010; 69(2): 86-92.

[17] Al Wadaani FA, Amin TT, Ali A, Khan AR. Prevalence and pattern of refractive errors among primary school children in Al Hassa, Saudi Arabia. Glob J Health Sci 2012; 5(1): 125-34.

[18] Castagno VD, Fassa AG, Vilela MA, Meucci RD, Resende DP. Moderate hyperopia prevalence and associated factors among elementary school students. Cien Saude Colet 2015; 20(5): 1449-58.

[19] Hashemi H, Fotouhi A, Mohammad K. The Tehran eye study: research design and eye examination protocol. BMC Ophthalmol 2003; 3: 8.

[20] Fan Q, Zhou X, Khor CC, Cheng CY, Goh LK, Sim X, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis of five Asian cohorts identifies PDGFRA as a susceptibility locus for corneal astigmatism. PLoS Genet 2011; 7(12): e1002402.

[21] Yamamah GA, Talaat Abdel Alim AA, Mostafa YS, Ahmed RA, Mahmoud AM. Prevalence of visual impairment and refractive errors in children of South Sinai, Egypt. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 2015; 22(4): 246-52.

[22] Chebil A, Jedidi L, Chaker N, Kort F, Limaiem R, Mghaieth F, et al. Characteristics of astigmatism in a population of Tunisian school-children. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol 2015; 22(3): 331-4.

[23] O'Donoghue L, Breslin KM, Saunders KJ. The changing profile of astigmatism in childhood: the NICER study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2015; 56(5): 2917-25.

[24] Pokharel GP, Negrel AD, Munoz SR, Ellwein LB. Refractive error study in children: results from Mechi Zone, Nepal. Am J Ophthalmol 2000; 129(4): 436-44.

[25] AI-Rowaily MA, Alanizi BM. Prevalence of uncorrected refractive errors among adolescents at King Abdul-Aziz Medical City, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. J Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2010; 1: 114.

[26] Al-Nuaimi A, Salama R, Eljack I. Study of refractive errors among school children Doha. World Fam Med J 2010; 8: 41-8.

[27] Prema N. Prevalence of refractive error in school children. Indian J Sci Technol 2011; 4(9): 1160-1.

[28] Wen G, Tarczy-Hornoch K, McKean-Cowdin R, Cotter SA, Borchert M, Lin J, et al. Prevalence of myopia, hyperopia, and astigmatism in non-hispanic white and Asian children: multiethnic pediatric eye disease study. Ophthalmology 2013; 120(10): 2109-16.

*Corresponding author:Samira Heydarian, Department of Optometry, School of Paramedical Science, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran.

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine2016年2期

Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine2016年2期

- Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine的其它文章

- Step-by-step external fixation of unstable pelvis with separate anterior and posterior modules

- Evaluation of entomopathogenic Bacillus sphaericus isolated from Lombok beach area against mosquito larvae

- Anti-hyperglycemic effects of aqueous Lenzites betulina extracts from the Philippines on the blood glucose levels of the ICR mice (Mus musculus)

- Evaluation of imatinib mesylate (Gleevec) on KAI1/CD82 gene expression in breast cancer MCF-7 cells using quantitative real-time PCR

- Feasibility of using melatonin as a new treatment agent for Ebola virus infection: A gene ontology study

- Inhibitory actions of Pseuderanthemum palatiferum (Nees) Radlk. leaf ethanolic extract and its phytochemicals against carbohydrate-digesting enzymes