Beijing’s Cultural Charm

By staff reporter ZHANG LI

Beijing’s Cultural Charm

By staff reporter ZHANG LI

Beijing’s traditional grassroots street folkwaysthrive alongside its magnificant imperial culture.

Courtyard Homes and Hutong

Courtyard homes (siheyuan) are the most representative residences in Beijing. It is said that since Beijing was appointed capital of the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), courtyard homes appeared in the city simultaneously with Beijing’s palaces, blocks, lanes and hutong. Old courtyard homes are omnipresent throughout the capital, and their carved beams, painted pillars and tranquil courtyards add a touch of understated elegance to this city.

The layout of a courtyard home takes the form of a quadrangle with buildings around it – the main room, east and west wings and back room. Of old they were known as “four-side homes” in reference to the courtyard thus enclosed on four sides. The building to the north facing south is considered the main room. Those adjoining the main house facing east and west are wing-rooms. The building that faces north is known as the back room. All are connected by beautifully decorated walkways. Usually, a screen wall inside the gate safeguards privacy, but superstition holds that it also protects the house from evil spirits. The spacious yard is an ideal place to plant pomegranate trees, jujubes, persimmons and Chinese flowering crabapple. These produce fragrant blooms, give welcome shade in summer, and luscious fruits in autumn.

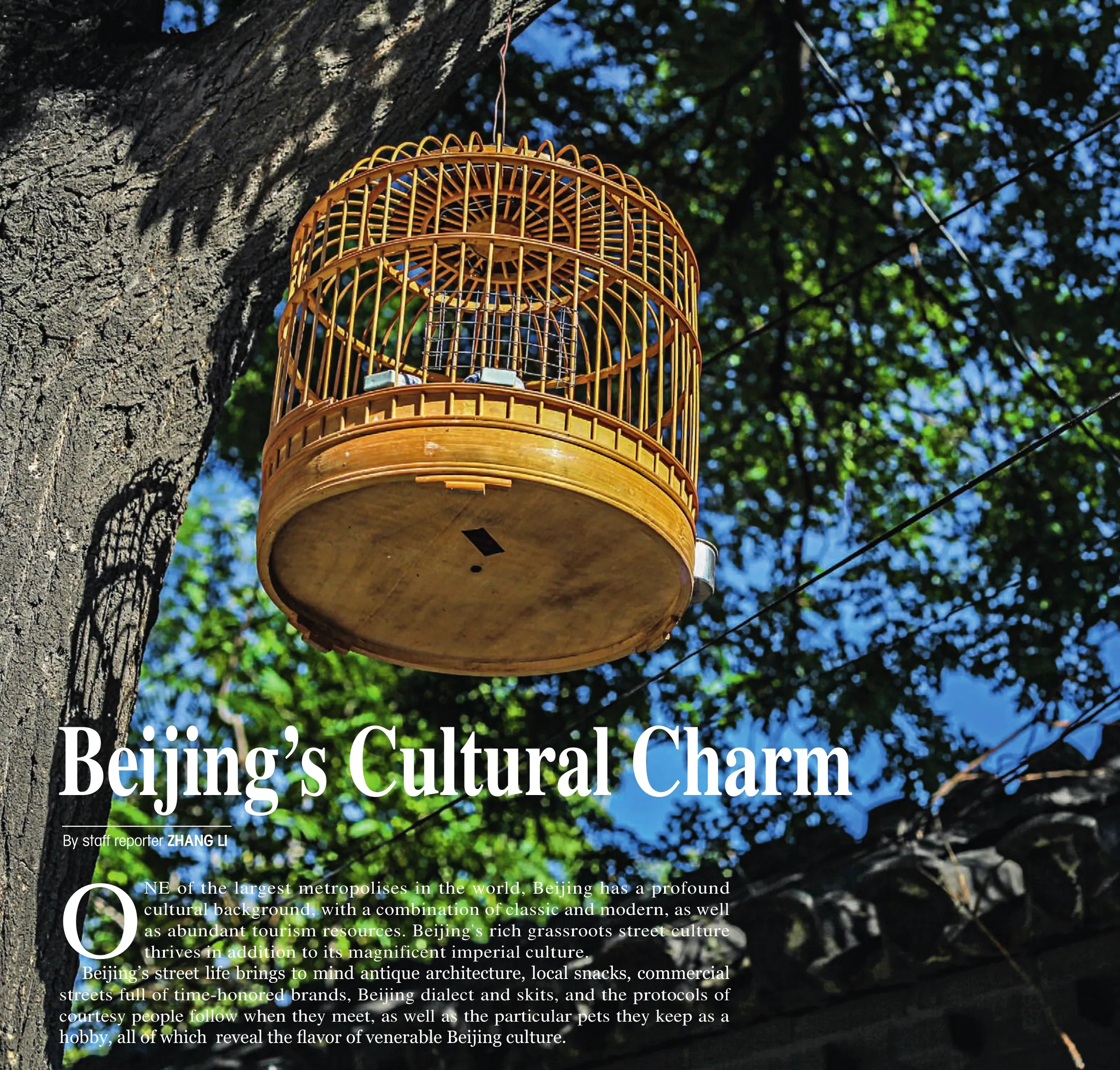

Beijing’s street life brings to mind antique architecture, local snacks, and commercial streets full of timehonored brands.

The hutong are also an ideal medium in whichto explore Beijing’s culture. The city now has more than 7,000 winding hutong. As the carrier of the city’s ancient culture, hutong bear witness to its historical changes. Hutong tours help tourists to better understand local people’s lives and traditions.

However, large-scale urban construction has made Beijing’s courtyard homes rare. In 2002, the city planned 25 historic site conservation districts in the old city. The book Records of Beijing Courtyard Homes includes 1,000 such precious courtyards.

A gourmet eatery on Xianyukou Hutong near Beijing’s Qianmen Street.

Time-honored Brands and Snacks

For old Beijing natives, time-honored brands

Beijing’s hutong Tour

Shichahai: Located in the city center, Shichahai has preserved its ancient aspect. This venerable district of lakes and waterways enjoys a sublime natural environment. In fine weather, one can stand on the ancient Yinding Bridge and gaze at the reflection of the faraway hills on the water surface and the willows along the banks swaying in the wind. The various handicrafts and whirligigs on display in nearby Yandai Xiejie market street dazzle the eye. In addition, a number of other historic sites, such as Prince Gong’s Mansion and the former residences of Soong Ching Ling and Mei Lanfang, as well as the Bell Tower and Drum Tower, cluster nearby.

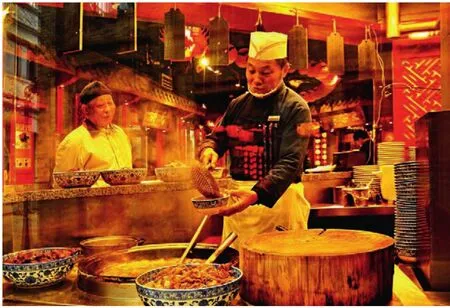

Liulichang: This famous cultural street is only one km to the south of Tian’anmen Square. Shops there sell a miscellany of antiques, calligraphic works and paintings. Some of these stores are time-honored brands, such as the Laixunge, Cathay Bookshop, Rongbaozhai, Daiyuexuan and Yidege.

Nanluoguxiang: Close to the Forbidden City, Nanluoguxiang is an 800-meter-long hutong. It lies at the center of an area which represents the best preserved hutong arrangement typical of the Great Capital of the Yuan Dynasty. Overlooking this north-south hutong, eight other hutong connect with it like well-ordered fish bones. Traditional folk inns and trendy boutiques add to its bountiful and unique charm. There tourists can visit the former residences of Qi Baishi and Mao Dun or enjoy stage dramas in the studio theater of the China Youth Art Theater off the hutong.

Dongjiaominxiang: Known as Legation Street, it served as the center of China’s diplomacy for 700 years. Aside Xijiaomingxiang, this 3-kmlong hutong is the longest in Beijing. The widely-renowned Adong Photo Studio is on the eastern section of the hutong. Many influential photos were developed here, the most famous being those appearing in Red Star over China by Edgar Snow. In the old days, a number of Western edifices were built here, such as churches, embassies, banks and clubs.represent not only quality, but also tradition, as typified by Donglaishun mutton hotpot, Quanjude roast duck, Liubiju pickles and Tongrentang traditional Chinese medicine. These brands are not just city icons; they are cultural phenomena that embody its historical traditions.

Time-honored brands are the quality goods that have survived centuries of commercial and handicraft competition. Sixty-seven of them concentrate mainly on handicrafts, catering, folk art, and culture. In obedience to the dictates of Confucianist culture, these brands focus on integrity of management, high quality, considerate service, and unique skills: the precious spiritual wealth that ensures the survival and development of these brands.

Founded in 1669, Tongrentang is a distinguished time-honored brand of the traditional Chinese medicine industry, and tradition holds that its name was bestowed by Qing Dynasty Emperor Kangxi himself. A former purveyor-by-appointment to the

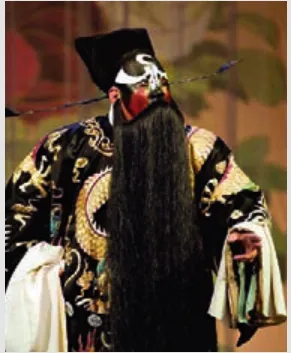

A stage photo from PekingOpera Farewell My Concubine.

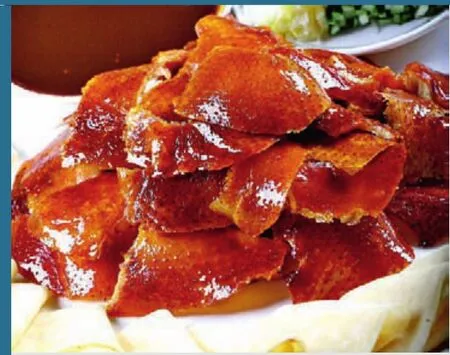

Beijing Cuisines

Roast duck: Peking duck is traditionally roasted in either a hanging or closed oven. A hanging oven is designed to roast ducks over an open fire fueled by orchard hardwood from jujube, peach or apricot trees. The closed oven is built of brick and fitted with metal grills. The oven is preheated by burning charcoal at its base. The duck is placed in the oven immediately after the fire burns out, allowing the meat to slowly cook through convection heat within the oven.

Two notable restaurants in Beijing which serve this dish are Quanjude and Bianyifang, both centuries-old establishments which have become household names, each with their own style: Quanjude is known for using the hanging oven roasting method, while Bianyifang employs the older technique of closed oven roasting. There are many ways of eating roast duck, but the best is to place it in a small wheatflour lotus leaf shaped pancake or wheatflour sesame tortilla, add strips of shallots and sweet brown noodle sauce, and roll it up for gustation.

Noodles with soybean paste: Beijingers, especially seniors, enjoy noodles with soybean paste. The fried soybean paste is the key ingredient. After noodles are boiled, vegetables, such as cucumber slices, summer radish slices or soybean sprouts, are added. In August 2011, when visiting U.S. Vice President Joe Biden ate noodles with soybean paste in a Beijing hutong, this dish went viral on China’s web.

Mutton hotpot: Dating as far back as the Yuan Dynasty, mutton hotpot has been popular since the Qing Dynasty. Among several banquets for thousands of court elders during the reigns of Emperors Kangxi and Qianlong, mutton hotpot was a must. Later it was introduced to the commonality and offered by Halal restaurants. In 1854, Zhengyanglou Restaurant opened outside Qianmen in Beijing and became the first Han restaurant to feature Mongolian hotpot. Lamb there is pre-cut into paper-thin slices, thus rendering it all the more delicious. In 1914, Donglaishun enticed Zhengyanglou’s cooks away with offers of higher pay and opened a restaurant specializing in mutton hotpot. After rounds of improvement, Donglaishun has gained a high reputation.

Manchu-Han Imperial Feast: The inception of the Manchu-Han Imperial Feast was in the Qing Dynasty. This amalgamation of Manchu and Han cuisine constituted one of the most sumptuous of Chinese banquets ever. Initially, the cuisines of Northeast China (Manchuria), Beijing, Shandong, and Zhejiang provinces predominated. Fujianese and Cantonese local cuisines, among others, also later featured at this imperial feast, which during the Qing Dynasty consisted of at least 108 unique dishes from the Manchu and Han Chinese culture, and was reserved solely for the imperial household. Culinary skills consisted of cooking methods from all over Imperial China. As the cultural gem and high-tide mark of Chinese cuisine, the feast is usually served in highend restaurants at exorbitant prices. A number of Beijing’s restaurants still feature imperial dishes, such as Najia Xiaoguan.imperial dispensary, Tongrentang enjoys a sound reputation both at home and abroad for its elaborate processing techniques and human capital, as well as its countless ingredient resources.

Having started out as a tea stand in Beixinqiao Street, Wuyutai has become the most profitable tea shop in Beijing after generations of hard work. Its excellent quality and reasonable prices induce many to travel far out of their way to buy Wuyutai tea.

Founded in 1853, Neiliansheng is well-known for its sturdy handmade cloth shoes. About 81-100 evenly distributed stitches of hempen thread are sewn into every square inch. The shop also records customers’ sizes and preferences, so that if a customer desires an additional pair, the new shoes can be made and delivered to order. The shop still preserves the tradition of producing custom made orthopedic shoes and otherwise satisfying special customer needs.

Beijing’s traditional snacks are the city’s history, taste and culture. One who has not been to the hutong, has not strolled around Beijing, so to speak, and one who has not sampled its snacks has not experienced the city.

A number of century-old shops offer Beijing snacks. Many integrate the flavors of the Han, Hui, Mongol and Manchu ethnicities, as well as the imperial snacks of the Ming and Qing dynasties. The more than 200 Beijing snacks include side dishes, tea cakes and night snacks, which differ in taste and cooking methods. Exquisite palace desserts such as pea cake and green bean rolls are ladies’ favorites. Meats like cooked pork or mutton tripe are men’s favorites; however, as these foods are mainly made from animal entrails, eating too much is not good for the health. In addition, visitors can also try sugar-coated haws on a stick, preserved fruit, plum syrup and almond tea.

Peking Opera

As the quintessence of Chinese culture, Peking Opera receives the adulation of local citizens. Walking on Beijing’s streets, one often hears locals singing strains of Peking Opera.

Peking Opera was born when the “Four Great Anhui Troupes” brought Anhui opera to Beijing in 1790 to entertain Emperor Qianlong on his 80th birthday. In collaboration with Handiao performers from Hubei Province, while also adopting the performance techniques of Kunqu Opera and Shaanxi Opera, as well as various folk melodies, Peking Opera formed through a process of continuous exchanges and combination. Developing rapidly as a courtly art, it achieved unprecedented prosperity during the Republic of China period (1912-1949).

Peking Opera performers employ four main skills. The first two are song and speech. The third is dance-acting. This includes pure dance, pantomime, and other types of dance. The final skill is combat, which includes both acrobatics, and fighting with all manner of weaponry. All of these skills are expected to be performed effortlessly, in keeping with the spirit of the art form.

During its 200-year history, Peking Opera has become more localized in libretto, spoken parts and rhyme. Moreover, it is not only accompanied by the musical instruments of various ethnic groups, but also integrates art and literature in a manner similar to Western opera.

Peking Opera’s facial makeup is an exaggerated art. It includes a dozen basic facial patterns, but there are numerous specific variations. Each design is unique to a specific character.

The patterns and coloring are thought to be derived from traditional Chinese color symbolism and divination of the lines on a person’s face, said to reveal their personality. Easily recognizable examples of coloring include red – which denotes uprightness and loyalty, white – which represents evil or crafty characters, and black – for characters of soundness and integrity.

Beijing’s traditional snacks are the city’s history, taste and culture. One who has not been to the hutong, has not strolled around Beijing, so to speak, and one who has not sampled its snacks has not experienced the city.

Main Roles in peking Opera

In addition to people’s natural attributes (gender and age) and social attributes (identity and profession), Peking Opera roles can be based on the characters Sheng, Dan, Jing, and Chou.

Sheng is the male role without facial makeup, and has numerous subtypes, such as Xiaosheng (stripling), Wusheng (young military officer), and Laosheng (dignified elder role). These characters have a gentle and cultivated disposition and wear understated costumes.

Dan refers to any female role in Peking Opera. Dan roles were originally divided into four subtypes. Old women were Laodan, martial women were Wudan or Daomadan, virtuous and elite women were Qingyi, and vivacious and unmarried women were Huadan.

Jing (Hualian) is a painted face male role. As a forceful character, a Jing must have a strong voice and make exaggerated gestures. There are three main types of Jing roles, including Dahualian, roles that involve singing, Erhualian, roles whose emphasis is more on physical performance, and Wuhualian, martial and acrobatic roles.

Chou is a male clown role. Chou roles can be divided into Wenchou, civilian roles such as merchants and jailers, and Wuchou, minor military roles. The Wuchou is one of the most demanding in Peking Opera, because of its combination of comic acting, acrobatics, and a strong voice. Chou characters are generally amusing and likable, if a bit foolish. Chou characters wear special face paint that differs from that of Jing roles. The defining characteristic of this type of face paint is a small patch of white chalk around the nose. This can represent either a mean and secretive nature, or a quick wit.