二次有机气溶胶的形成及其毒理效应

曹军骥,李建军

(1.中国科学院地球环境研究所,西安 710061;2.中国科学院气溶胶化学与物理重点实验室,西安 710061;3. 黄土与第四纪地质国家重点实验室,西安 710061)

二次有机气溶胶的形成及其毒理效应

曹军骥1,2,李建军1,3

(1.中国科学院地球环境研究所,西安 710061;2.中国科学院气溶胶化学与物理重点实验室,西安 710061;3. 黄土与第四纪地质国家重点实验室,西安 710061)

有机物是大气气溶胶中非常重要的化学组分,对我国空气污染及灰霾事件发生具有显著的贡献,是当前大气化学研究的最前沿课题之一。有机气溶胶中包含大量有毒物质(如多环芳香烃、多氯联苯及有机胺类等),直接危害人体健康。目前气溶胶中有机组分的体内/体外生物毒性研究多集中于污染源直接排放的一次颗粒物,对于大气中二次有机气溶胶的形成和毒性效应的关注很少。本文以多环芳烃、有机胺及自然源萜烯类挥发性有机物为例,简要综述了大气中二次有机气溶胶的形成及其生物毒性效应,重点关注这些二次有机气溶胶的形成对母体有机组分生物毒性的增强作用,以增进对大气气溶胶污染的健康危害认识。

二次有机气溶胶;毒性;多环芳烃;有机胺;萜烯

近年来随着经济社会的快速发展,污染物的大量排放使得我国大部分城市遭受了严重的空气污染,重霾天气时有发生(Liu et al,2013;Xu et al,2013;Huang et al,2014;Li and Zhang, 2014)。空气中悬浮的颗粒物(Particulate matter,PM)亦称大气气溶胶(Aerosol),由不同类型化学组分组成(戴文婷等,2011;孙涛等,2013),不仅对气候、环境具有重要的影响,且能对人体健康产生不同程度的危害(Davidson et al,2005;Ito et al,2006;Schlesinger,2007;曹军骥,2014)。与可吸入颗粒物(PM10,空气动力学当量直径小于等于10 μm的颗粒物)相比,细颗粒物(PM2.5,空气动力学当量直径小于等于2.5 μm的颗粒物)对人体健康的危害更大(曹军骥,2012;Schwartz and Neas,2000),因为其粒径更小,细颗粒物在大气中的停留时间增加,比表面积大易吸附金属和毒性有机物,且通过呼吸进入人体肺部的能力更强(PM1甚至可达肺泡)(Seagrave et al,2006;Happo et al,2008;Boldo et al,2011;曹军骥,2014)。大量流行病学研究表明,个体细颗粒物及其化学组分暴露与呼吸道疾病、心血管疾病、肺癌等疾病发病率及死亡率的增加存在不同程度的显著相关关系(Pope et al,2002)。最新研究表明,全球范围内室外空气污染每年会造成330万人的过早死亡,其中主要分布在亚洲地区(Lelieveld et al,2016)。同时,Thurston et al(2016)也证实空气中的细颗粒物会提高死亡风险系数。

由于颗粒物的微尺度效应、比表面积和化学构成的差异,其所产生的生物效应也不同。早在20世纪后期,国内外学者就已经发现大气颗粒物中的特定化学组分对人体健康具有一定的危害性。例如除颗粒物本身对人体呼吸道系统的产生危害之外,多环芳烃(PAHs)类有机物的存在对人体具有致畸、致癌和致突变毒性效应(Ohura et al,2004;Srogi,2007)。而大气颗粒物中的铅、砷、汞等重金属组分可通过生态系统的富集作用影响到人体健康(Utsunomiya et al,2004)。后来的流行病学研究更证明了大气颗粒物中的不同化学组分对人体健康的影响存在一定的差异。Cao et al(2012)对西安长达5年的研究数据发现,PM2.5中OC、EC、、、Cl-、Cl和Ni对全病因死亡率、心血管疾病死亡率和呼吸系统死亡率有显著影响。其中全病因死亡率和心血管疾病死亡率与的关系高于其与PM2.5质量浓度的关系。此外,研究认为颗粒物的人体健康造成危害的主要作用机制是大气颗粒物诱导的氧化应激和炎症反应(Pavagadhi et al,2013)。PM2.5刺激肺部中性粒细胞聚集、肿瘤坏死因子释放、氧化损伤等毒性效应是导致呼吸和心血管系统疾病的主要因素之一。因此大气颗粒物诱导的活性氧簇的生成和炎症指标的变化是研究关注的焦点,可以帮助理解颗粒物对人体健康危害的机理(Spector,2000;Seifried et al,2007)。

颗粒物及污染气体会在大气环境中与O3、OH自由基及NOx等氧化剂发生光化学氧化反应形成二次粒子,该氧化过程对大气颗粒物的健康及毒理效应具有十分重要的影响。Verma et al(2015)结合气溶胶质谱仪(Aerosol mass spectrometer,AMS)和二硫苏糖醇(Dithiothreitol,DTT)试验法表征活性氧簇(Reactive oxygen species,ROS)的研究表明,PM2.5的水溶性化学组分中,有机物对ROS的贡献更甚于金属物质;其中更氧化的含氧有机气溶胶(More-oxidized oxygenated organic aerosol,MO-OOA)与生物质燃烧有机气溶胶(Biomass burning organic aerosol,BBOA)的贡献更甚于其他有机组分。Liu et al(2014)采用正交矩阵因子分解法(Positive matrix factorization,PMF)对北京市PM2.5的来源进行了解析,并分析了不同来源与ROS的关系,结果表明二次源是北京市PM2.5的氧化潜能及炎症效应的重要贡献因子。然而,目前国内外对二次有机气溶胶在大气中形成及其毒理效应的研究很少。本文主要从分子角度出发,简述几种典型化合物在大气氧化过程中发生的毒理性质改变,阐明大气中二次有机气溶胶的形成对人体健康的影响。

1 多环芳烃的氧化

多环芳烃(Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons,PAHs)类化合物对人体具有显著的致癌、致畸及致突变效应,是气溶胶中最受关注的有机组分之一。流行病学研究表明暴露于含有PAHs的焦炉、厨房和香烟烟气等的人群患有肺癌的几率更高。PAHs通过生物转化形成强活性中间体附着在细胞大分子中,从而激活了其致突变性和致癌活性(特别是DNA)。大量关于单体PAHs代谢物对动物致瘤性的系统研究表明,邻位或所谓的靶-区域的二醇环氧化物是PAHs衍生物最终诱变和致癌的原因之一(Jernstrom et al,1984;Jernstrom and Graslund,1994)。这些二醇的环氧化物很容易被环氧化物开环转换成带电碳离子,成为烷基并共价结合到DNA碱基和蛋白质的亲核点位。PAHs具有脂溶性,因而能够吸附在哺乳动物的肺、肠和皮肤中。Weyand 和 Bevan(1986)对喂食有PAHs微晶体与灌注PAHs溶液的雌性大鼠的肺保留时间进行研究,结果表明PAHs不能迅速从呼吸道中清除。根据PAHs对人体和动物的致癌风险研究,美国国家环保局在国家大气排放清单(NAEI)中规定了16种优先控制PAHs(USEPA,1997)。由于其健康风险,很多国家都设立了空气质量监测网络来监测环境空气中PAHs的含量。例如日本环保署自1997年开始了PAHs的检测(Japan Environmental Agency,1997)。

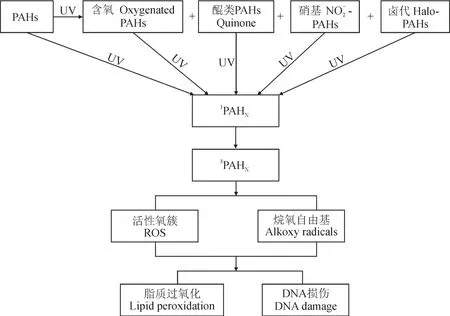

PAHs在大气中的一系列化学反应,如氧化和硝化反应,可以改变一次排放的母体PAHs的性质及毒性(Atkinson and Arey,1994;沈国锋和王格慧,2012)。含氧多环芳烃(Oxygenated-PAHs,OPAHs)含有一个或多个羰基,其毒性比相应的母体PAHs毒性更大。Wang et al(2011)发现PM2.5中的OPAHs对艾姆斯沙门氏菌直接作用的诱变性与致突变性比PAHs高出200%。OPAHs在不同类型的颗粒物中,如空气、柴油和汽油尾气颗粒中都有检出(Jakober et al,2006;Jakober et al,2007)。OPAHs也通常在PAHs大气光化学反应过程中形成(Wang et al,2011)。OPAHs的强毒性已引起越来越多的关注。Wei et al(2010)研究了PM2.5中蒽醌(Anthraquinone,AQ)和24种PAHs的氧化应激反应,发现交通站的两名保安人员体内蒽醌含量和氧化应激的增加之间有很强的相关性。蒽醌已被国际癌症研究机构列为对人类可能的致癌物质(IARC,2013)。Ringuet et al(2012)发现OPAHs对人体健康的不利影响可能与其在PM2.5中的占比有关。含氮多环芳烃(Nitrated-PAHs,NPAHs)由于其显著毒性已备受关注。在人体细胞和细菌菌株为基础的分析试验中,大多数NPAHs比其母体PAHs表现出更高的致突变性和致癌性(Durant et al,1996;Yang et al,2010)。大气中NPAHs的主要来源分为两种:直接排放(如从柴油发动机)及通过大气反应二次生成(Phousongphouang and Arey,2003;Reisen and Arey,2005)。大气中PAHs的转换可以通过与OH或NO3自由基和NO2的气态反应,或通过与NO2的多相反应转化为NPAHs(Atkinson and Arey,1994;Zhou and Wenger,2013;Roueintan et al,2014)。以皮肤损害(包括皮肤癌)为例,多环芳烃及其光氧化生成的OPAHs、NPAHs及其他产物的健康毒性机制如图1所示。多环芳烃在光照条件下氧化生成OPAHs、NPAHs及卤代多环芳烃等产物,母体PAHs及其产物继续在光照条件下生成单线态氧(1O2)及过氧自由基离子等ROS产物,或与其他溶剂反应或脱去氢原子生成烷氧自由基。生成的ROS及烷氧自由基均具有显著的脂质过氧化作用及DNA损伤,对人体健康具有一定的毒性作用(Fu et al,2012)。

图1 多环芳烃及其光氧化产物对皮肤损伤的生物毒性机制(Fu et al,2012)Fig.1 Bio-toxicity mechanism of PAHs and their photochemical products on skin damage (Fu et al, 2012)

2 有机胺的形成及氧化

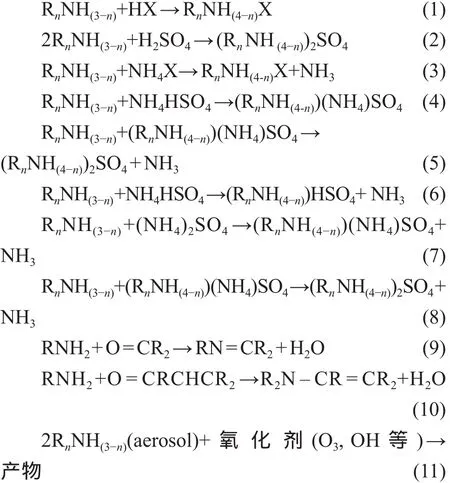

有机胺(Amines)是氨分子中氢原子被烷基或芳基取代而生成的衍生物。研究表明,即使在氨存在的情况下,只有氨浓度水平14%—23%的胺也具有较强的碱性(Sorooshian et al,2008)。Chang and Novakov(1975)认为有机胺的存在是由于缩合反应,但Dod et al(1984)指出它们可能是高温下烟灰粒子表面上的碳-氧复合物与NH3或NO反应生成的。Qiu and Zhang(2013)总结了目前大气中气态前体物通过非均相氧化生成有机胺的主要反应机制,包括酸催化反应、自由基氧化等途径(反应式1—11)。

烷基胺(Alkyl-amine),如甲胺、二甲胺、乙胺、二乙胺、丙胺、丁胺和二丁胺等,其气味恶臭、毒性较强,是重要的大气污染物,被广泛应用于化学和制药工业中作为中间物(Pan et al,1997;Namiesnik et al,2003)。烷基胺能够刺激皮肤、粘膜和呼吸道并引起过敏反应。芳香胺(Aromaticamine),如吗啉、苯胺、氯代苯胺、哌嗪、萘胺、氨基苯酚、甲苯二胺和4-氨基联苯具有生物活性,是具有毒性和致癌性的环境污染物,被广泛地应用于工业制染料、化妆品、药品、橡胶、纺织、农用化学品等工业中,并在许多化学合成中作为试剂的中间体(Palmiotto et al,2001;Zhu and Aikawa,2004)。汽车尾气、木材和橡胶的燃烧、烟草烟雾和烤肉、鱼的过程中也会释放出芳香胺(Ge et al,2011)。流行病学研究表明,芳香胺和患癌症风险之间有一定相关性。芳香胺可以被N-乙酰转移酶催化形成代谢产物,并最终产生其他的致癌化学物质。越来越多的证据表明,吸烟者中多发的膀胱癌主要是由香烟烟雾中的芳香胺所引起的。

有机胺也可与大气中的氧化剂,如O3和NOx反应进一步生成新的二次有机气溶胶(Murphy et al,2007)。有机酸如苹果酸(Barsanti and Pankow,2006)或顺式十八碳烯酸(Zahardis et al,2008)与有机胺反应,得到氮原子连接于酰基(R—C ═ O)的酰胺。烷基胺可与亚硝酸盐反应,形成致癌的亚硝胺 (Nitrosamine)(Skarping et al,1986;Santagati et al,2002)。很多种致癌的亚硝胺如二甲基亚硝胺是由OH自由基与二甲胺(Lindley et al,1979;Grosjean,1991)、二甲肼(Ge et al,2011)和三甲胺等反应生成的(Pitts et al,1978)。这些非均相反应产生的二次有机胺类污染物可以改变气溶胶的毒性效应。

3 萜烯类VOCs氧化

大气中萜烯类挥发性有机物(Volatile organic compounds,VOCs)包括异戊二烯、蒎烯、柠檬烯及沉香醇等物质,是一类非常重要的是自然源(如树木、草类)VOCs产物,其在大气的含量仅次于非甲烷烃(Non-methane hydrocarbon,NMHC)。研究表明,全球自然源排放的VOCs含量约比人为源VOCs高一个数量级(Guenther et al,2006)。高浓度的自然源VOCs排放能促进大气中二次有机气溶胶的生成,从而通过吸收或散射太阳光的直接效应或作为云凝结核(Cloud condensation nuclei,CCN)的间接效应影响大气辐射强迫(Turpin and Huntzicker,1995;Kanakidou et al,2005;Kawamura and Yasui,2005)。室内自然源萜烯类VOCs氧化引起的健康效应备受关注,因为室内家具及服饰等消费品均可排放出大量的萜烯类挥发性有机物,并能与空气中的O3及氮氧化物等氧化剂发生氧化反应,生成二次有机气溶胶,影响室内人体的健康。

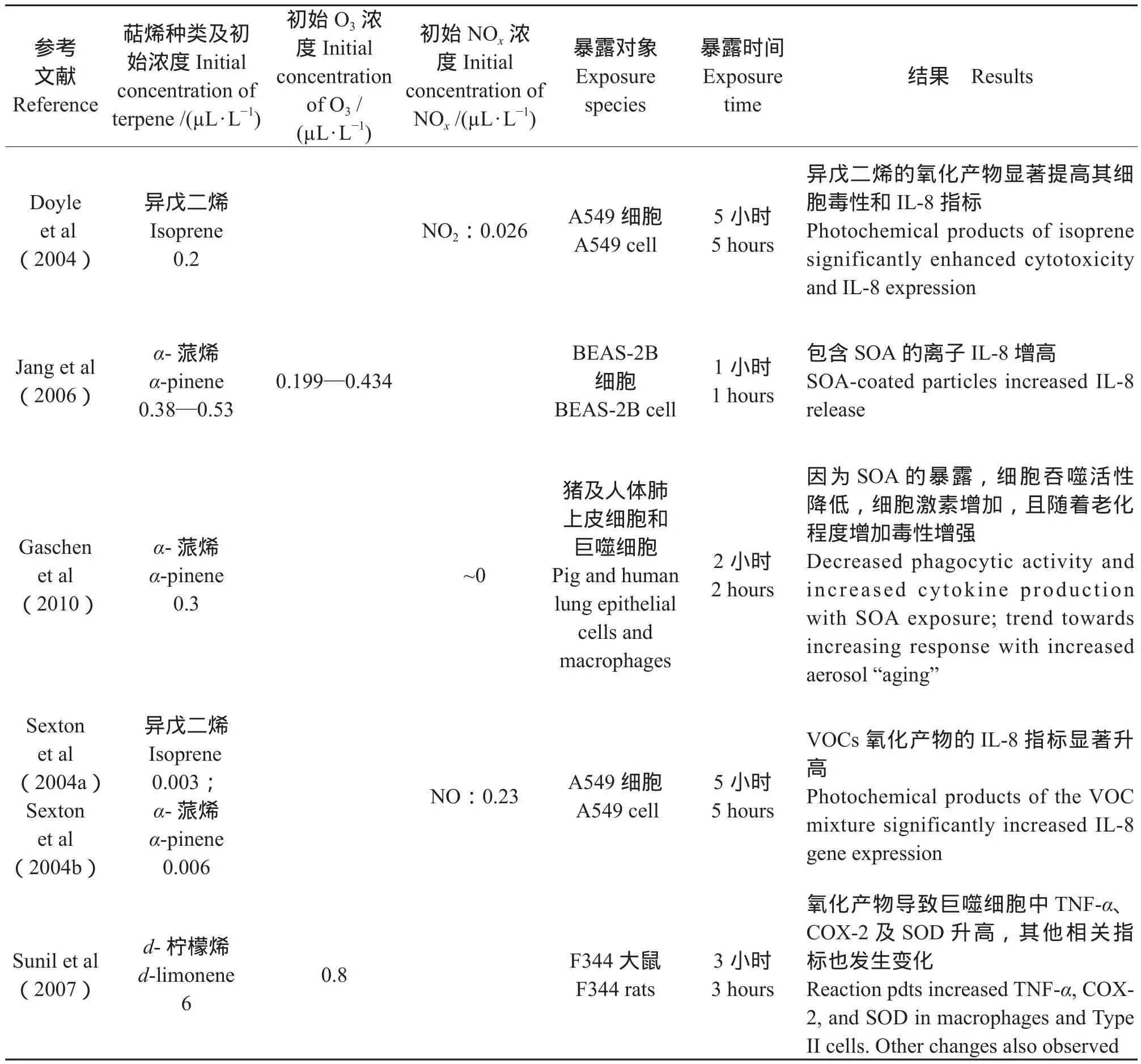

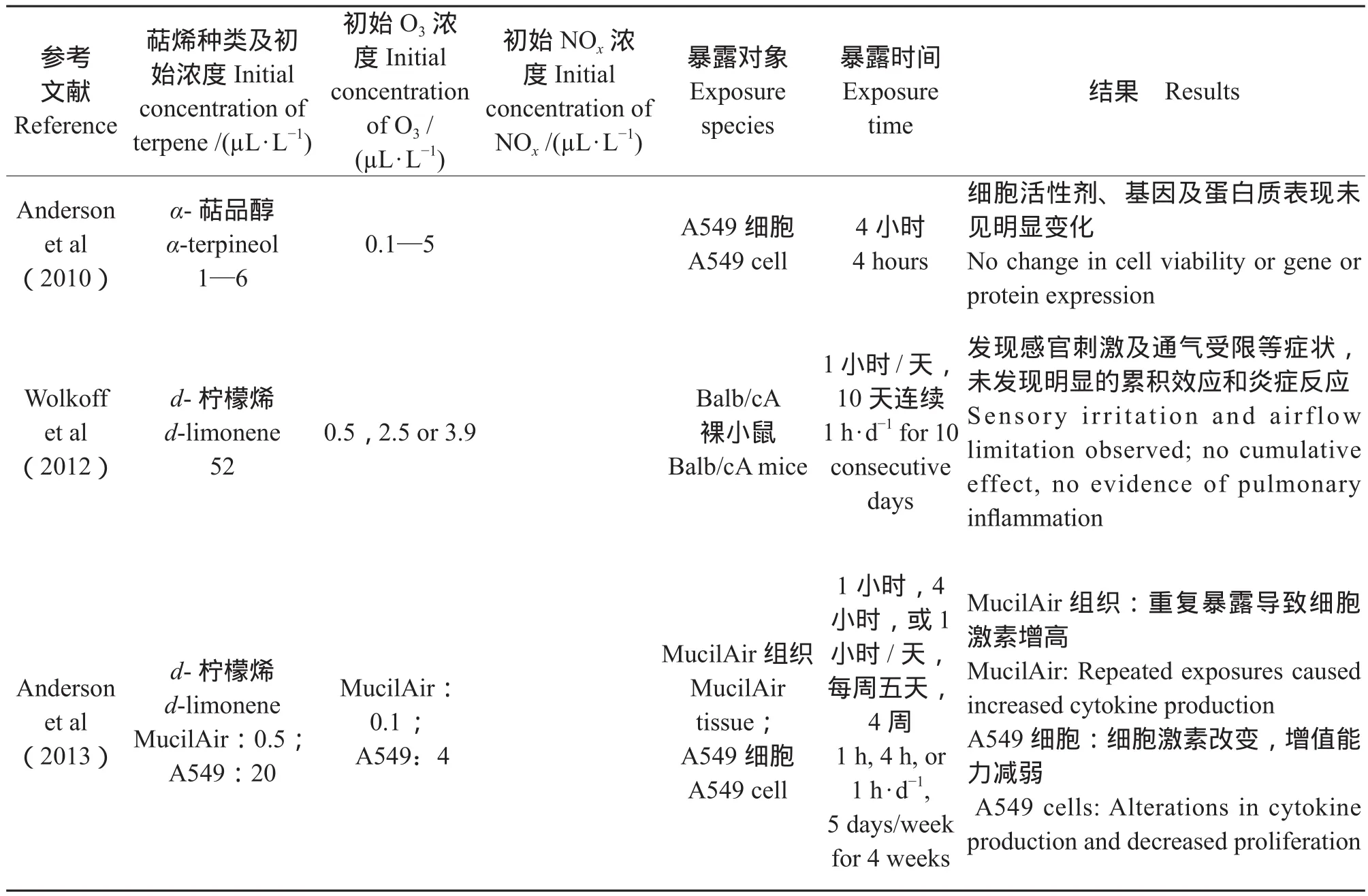

Chen et al(2011)通过烟雾箱实验证明了α-蒎烯(α-pinene)、沉香醇(Linalool)及柠檬烯(Limonene)等自然源挥发性有机物(Biogenic volatile organic compounds,BVOCs)与臭氧发生反应形成的二次有机气溶胶促进了大气颗粒诱发细胞活性氧簇的能力,因此可能对人体产生危害。如表1所示,多数体内及体外实验均证实暴露于萜烯类VOCs及一定氧化剂(O3或NOx)条件下,其SOA的生成会增加细胞的炎症反应或者降低细胞活性。如Doyle et al(2004)使用烟雾箱中将A549及人体支气管上皮细胞暴露于1,4-丁二烯及异戊二烯等自然源VOCs,并往烟雾箱中引入太阳光和NO促使VOCs等发生光化学氧化反应。其中异戊二烯的主要产物包括异丁烯醛、甲基乙烯醛等物质。尽管异戊二烯本身也对具有一定的毒性,但其大气氧化产物的细胞毒性明显增强。Jang et al(2006)通过体外实验,使用磁性纳米粒子暴露系统将BEAS-2B 细胞引入蒎烯及萜品油烯所产生的二次有机气溶胶中,并使用乳酸脱氢酶作为细胞毒性指标,IL-6(白细胞介素-6),IL-8(白细胞介素-8)和 TNF-α(肿瘤坏死因子-α)等作为炎症指标,证实蒎烯类SOA能明显提高IL-8含量。Gaschen et al(2010)的研究证明当α-蒎烯产生的SOA浓度达到实际环境相当浓度(约104个/cm3)时,2小时左右即可引起中等程度的细胞反应。

表1 萜烯类物质氧化产物的毒理学及人体暴露研究总结Tab.1 Summary of terpene oxidation product toxicology and controlled human exposure studies

(续表1 Continued Tab.1)

尽管以上烟雾箱的体外实验还存在如条件控制不充分等缺陷,但均能证实大气中萜烯类VOCs氧化生成的二次有机气溶胶比起母体化合物具有更强的生物毒性效应。考虑到室内环境中萜烯类化合物的排放量,这对居民的人体健康具有十分重要的意义(Rohr,2013)。

4 结语

大气中有机气溶胶包括众多对人体有害的化合物,如多环芳烃、有机胺、多氯联苯及邻苯二甲酸酯等物质,其健康效应已经受到国内外学者的高度关注。目前很多研究证实大气中气相或颗粒相中有机物可进一步与空气中氧化剂反应,生成产物甚至比其母体化合物的毒性更强。但目前国际上对二次有机气溶胶形成及生物毒性效应的研究非常缺乏,亟需加强如下两方面的研究。

(1)二次有机气溶胶的化学与其毒理学特征相结合的系统研究。当前二次有机气溶胶研究中有关化学形成及生物效应机制的联合研究不够深入,为对其健康效应有深入的了解,需要全面模拟实际环境下二次有机气溶胶的形成过程,并对其毒理效应进行更加深入的分析,如不同氧化剂、反应途径等对气溶胶活性氧簇、炎症指标以及蛋白质的影响。

(2)特定污染源二次有机气溶胶的毒理特征研究。了解不同污染源(如燃煤排放、机动车尾气及生物质燃烧等)产生二次有机气溶胶的生物效应的差异,有助于制定有针对性且有效的控制对策及法规,益于公众健康。

致谢:本文写作过程中得到了何建辉、何世恒研究员的帮助,在此表示感谢。

曹军骥. 2012. 我国PM2.5污染现状与控制对策[J].地球环境学报, 3(5): 1030–1036. [Cao J J. 2012. Pollution status and control strategies of PM2.5in China [J].Journal of Earth Environmen, 3(5): 1030–1036.]

曹军骥. 2014. PM2.5与环境[M]. 北京:科学出版社. [Cao J J. 2014. PM2.5& environment [M]. Beijing: Science Press.]

戴文婷, 李建军, 成春雷, 等. 2011. 中国中东部高山和城市夏季大气气溶胶浓度及粒径分布[J].地球环境学报, 2(1): 263–271. [Dai W T, Li J J, Cheng C L, et al. 2011.Concentrations and size distributions of summertime atmospheric aerosols at urban and alpine sites in east and central China [J].Journal of Earth Environmen, 2(1): 263–271.]

沈国锋, 王格慧. 2012. 南京大气PM2.5中羟基多环芳烃分子组成和季节变化特征[J].地球环境学报, 3(5): 1066–1069. [Shen G F, Wang G H. 2012. Molecular composition and seasonal variation of hydroxylated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in atmospheric PM2.5of Nanjing, China [J].Journal of Earth Environmen, 3(5): 1066–1069.]

孙 涛, 王格慧, 李建军. 2013. 西安市夏季大气中生物二次有机气溶胶的分子组成与粒径分布[J].地球环境学报, 4(1): 1230–1235. [Sun T, Wang G H, Li J J. 2013. The molecular composition and mass-size distribution of biogenic secondary organic aerosol from Xi’an [J].Journal of Earth Environmen, 4(1): 1230–1235.]

Anderson S E, Jackson L G, Franko J, et al. 2010. Evaluation of dicarbonyls generated in a simulated indoor air environment using an in vitro exposure system [J].Toxicological Sciences, 115: 453–461.

Anderson S E, Khurshid S S, Meade B J, et al. 2013. Toxicological analysis of limonene reaction products using an in vitro exposure system [J].Toxicology in Vitro, 27: 721–730.

Atkinson R, Arey J. 1994. Atmospheric chemistry of gasphase polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: Formation of atmospheric mutagens [J].Environmental Health Perspectives, 102: 117–126.

Barsanti K C, Pankow J F. 2006. Thermodynamics of the formation of atmospheric organic particulate matter by accretion reactions-part 3: Carboxylic and dicarboxylic acids [J].Atmospheric Environment, 40: 6676–6686.

Boldo E, Linares C, Lumbreras J, et al. 2011. Health impact assessment of a reduction in ambient PM2.5levels in Spain [J].Environment International, 37: 342–348.

Cao J J, Xu H, Xu Q, et al. 2012. Fine particulate matter constituents and cardiopulmonary mortality in a heavily polluted Chinese city [J].Environmental Health Perspectives, 120: 373–378.

Chang S G, Novakov T. 1975. Formation of pollution particulate nitrogen compounds by NO-soot and NH3-soot gas-particle surface reactions [J].Atmospheric Environment, 9: 495–504.

Chen X, Hopke P K, Carter W P L. 2011. Secondary organic aerosol from ozonolysis of biogenic volatile organic compounds: Chamber studies of particle and reactive oxygen species formation [J].Environmental Science & Technology, 45: 276–282.

Davidson C I, Phalen R F, Solomon P A. 2005. Airborne particulate matter and human health: A review [J].Aerosol Science and Technology, 39: 737–749.

Dod R L, Gundel L A, Benner W H, et al. 1984. Nonammonium reduced nitrogen species in atmospheric aerosol-particles [J].Science of the Total Environment, 36: 277–282.

Doyle M, Sexton K G, Jeffries H, et al. 2004. Effects of 1,3-butadiene, isoprene, and their photochemical degradation products on human lung cells [J].Environmental Health Perspectives, 112: 1488–1495.

Durant J L, Busby W F, La fl eur A L, et al. 1996. Human cell mutagenicity of oxygenated, nitrated and unsubstituted polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons associated with urban aerosols [J].Mutation Research-Genetic Toxicology, 371: 123–157.

Fu P P, Xia Q, Sun X, et al. 2012. Phototoxicity and environmental transformation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs)-light-induced reactive oxygen species, lipid peroxidation, and DNA damage [J].Journal of Environmental Science and Health. Part C, Environmental Carcinogenesis & Ecotoxicology Reviews, 30: 1–41.

Gaschen A, Lang D, Kalberer M, et al. 2010. Cellular responses after exposure of lung cell cultures to secondary organic aerosol particles [J].Environmental Science & Technology, 44: 1424–1430.

Ge X, Wexler A S, Clegg S L. 2011. Atmospheric amines–partⅠ: A review [J].Atmospheric Environment, 45: 524–546.

Grosjean D. 1991. Atmospheric chemistry of toxic contaminants. 6. Nitrosamines-dialkyl nitrosamines and nitrosomorpholine [J].Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association, 41: 306–311.

Guenther A, Karl T, Harley P, et al. 2006. Estimates of global terrestrial isoprene emissions using megan (model of emissions of gases and aerosols from nature) [J].Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 6: 3181–3210.

Happo M S, Hirvonen M R, Halinen A I, et al. 2008. Chemical compositions responsible for inflammation and tissuedamage in the mouse lung by coarse and fi ne particulate samples from contrasting air pollution in Europe [J].Inhalation Toxicology, 20: 1215–1231.

Huang R J, Zhang Y, Bozzetti C, et al. 2014. High secondary aerosol contribution to particulate pollution during haze events in China [J].Nature, 514: 218–222.

International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). 2013. Monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans: Some chemicals present in industrial and consumer products, food and drinking-water [M]. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer.

Ito K, Christensen W F, Eatough D J, et al. 2006. PM source apportionment and health effects: 2. An investigation of intermethod variability in associations between sourceapportioned fine particle mass and daily mortality in Washington, DC [J].Journal of Exposure Science and Environmental Epidemiology, 16: 300–310.

Jakober C A, Charles M J, Kleeman M J, et al. 2006. LC-MS analysis of carbonyl compounds and their occurrence in diesel emissions [J].Analytical Chemistry, 78: 5086–5093.

Jakober C A, Riddle S G, Robert M A, et al. 2007. Quinone emissions from gasoline and diesel motor vehicles [J].Environmental Science & Technology, 41: 4548–4554.

Jang M, Ghio A J, Cao G. 2006. Exposure of BEAS-2B cells to secondary organic aerosol coated on magnetic nanoparticles [J].Chemical Research in Toxicology, 19: 1044–1050.

Japan Environmental Agency. 1997. Quality of the environment in Japan [M]. Tokyo: Environmental Agency, Government of Japan.

Jernstrom B, Lycksell P O, Graslund A, et al. 1984. Spectroscopic studies of DNA complexes formed after reaction with anti-benzo[a]pyrene-7,8-dihydrodiol-9,10-oxide enantiomers of different carcinogenic potency [J].Carcinogenesis, 5:1129–1135.

Jernstrom B, Graslund A. 1994. Covalent binding of benzo[a] pyrene-7,8-dihydrodiol-9,10-epoxides to DNA: Molecular structures, induced mutations and biological consequences [J].Biophysical Chemistry, 49: 185–199.

Kanakidou M, Seinfeld J H, Pandis S N, et al. 2005. Organic aerosol and global climate modelling: A review [J].Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 5: 1053–1123.

Kawamura K, Yasui O. 2005. Diurnal changes in the distribution of dicarboxylic acids, ketocarboxylic acids and dicarbonyls in the urban Tokyo atmosphere [J].Atmospheric Environment, 39: 1945–1960.

Lelieveld J, Evans J S, Fnais M, et al. 2015. The contribution of outdoor air pollution sources to premature mortality on a global scale [J].Nature, 525: 367–371.

Li M, Zhang L. 2014. Haze in China: Current and future challenges [J].Environmental Pollution, 189: 85–86.

Lindley C R C, Calvert J G, Shaw J H. 1979. Rate studies of the reactions of the (CH3)2N radical with O2, NO, and NO2[J].Chemical Physics Letters, 67: 57–62.

Liu Q Y, Baumgartner J, Zhang Y X, et al. 2014. Oxidative potential and in fl ammatory impacts of source apportioned ambient air pollution in Beijing [J].Environmental Science & Technology, 48: 12920–12929.

Liu X G, Li J, Qu Y, et al. 2013. Formation and evolution mechanism of regional haze: A case study in the megacity Beijing, China [J].Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 13: 4501–4514.

Murphy S M, Sorooshian A, Kroll J H, et al. 2007. Secondary aerosol formation from atmospheric reactions of aliphatic amines [J].Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 7: 2313–2337.

Namiesnik J, Jastrzebska A, Zygmunt B. 2003. Determination of volatile aliphatic amines in air by solid-phase microextraction coupled with gas chromatography with fl ame ionization detection [J].Journal of Chromatography A, 1016: 1–9.

Ohura T, Amagai T, Fusaya M, et al. 2004. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in indoor and outdoor environments and factors affecting their concentrations [J].Environmental Science & Technology, 38: 77–83.

Palmiotto G, Pieraccini G, Moneti G, et al. 2001. Determination of the levels of aromatic amines in indoor and outdoor air in Italy [J].Chemosphere, 43: 355–361.

Pan L, Chong J M, Pawliszyn J. 1997. Determination of amines in air and water using derivatization combined with solidphase microextraction [J].Journal of Chromatography A, 773: 249–260.

Pavagadhi S, Betha R, Venkatesan S, et al. 2013. Physicochemical and toxicological characteristics of urban aerosols during a recent indonesian biomass burning episode [J].Environmental Science and Pollution Research International, 20: 2569–2578.

Phousongphouang P T, Arey J. 2003. Sources of the atmospheric contaminants, 2-nitrobenzanthrone and 3-nitrobenzanthrone [J].Atmospheric Environment, 37: 3189–3199.

Pitts J N, Grosjean D, Vancauwenberghe K, et al. 1978. Photooxidation of aliphatic-amines under simulated atmospheric conditions-formation of nitrosamines, nitramines, amides, and photo-chemical oxidant [J].Environmental Science & Technology, 12: 946–953.

Pope C A, Burnett R T, Thun M J, et al. 2002. Lung cancer, cardiopulmonary mortality, and long-term exposure to fi ne particulate air pollution [J].Journal of the American Medical Association, 287(9): 1132–1141.

Qiu C, Zhang R. 2013. Multiphase chemistry of atmospheric amines [J].Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics, 15: 5738–5752.

Reisen F, Arey J. 2005. Atmospheric reactions influence seasonal PAH and nitro-PAH concentrations in the Los Angeles Basin [J].Environmental Science & Technology, 39(1): 64–73.

Ringuet J, Leoz-Garziandia E, Budzinski H, et al. 2012. Particle size distribution of nitrated and oxygenated polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (NPAHs and OPAHs) on traf fi c and suburban sites of a European megacity: Paris (France) [J].Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 12(6): 8877–8887.

Rohr A C. 2013. The health signi fi cance of gas- and particlephase terpene oxidation products: A review [J].Environment International, 60: 145-162.

Roueintan M M, Cho J, Li Z. 2014. Kinetics investigation of reaction of naphthalene with OH radicals at 1—3 torr and 240—340 k [J].International Journal of Chemical Kinetics, 46: 578–586.

Santagati N A, Bousquet E, Spadaro A, et al. 2002. Analysis of aliphatic amines in air samples by HPLC with electrochemical detection [J].Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis, 29: 1105–1111.

Schlesinger R B. 2007. The health impact of common inorganic components of fi ne particulate matter (PM2.5) in ambient air: A critical review [J].Inhalation Toxicology, 19: 811–832.

Schwartz J, Neas L M. 2000. Fine particles are more strongly associated than coarse particles with acute respiratory health effects in schoolchildren [J].Epidemiology, 11: 6–10.

Seagrave J, McDonald J D, Bedrick E, et al. 2006. Lung toxicity of ambient particulate matter from southeastern US sites with different contributing sources: Relationships between composition and effects [J].Environmental Health Perspectives, 114: 1387–1393.

Seifried H E, Anderson D E, Fisher E I, et al. 2007. A review of the interaction among dietary antioxidants and reactive oxygen species [J].Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry, 18: 567–579.

Sexton K, Adgate J L, Ramachandran G, et al. 2004a. Comparison of personal, indoor, and outdoor exposures to hazardous air pollutants in three urban communities [J].Environmental Science & Technology, 38: 423–430.

Sexton K, Jeffries H E, Jang M, et al. 2004b. Photochemical products in urban mixtures enhance inflammatory responses in lung cells [J].Inhalation Toxicology, 16: 107–114.

Skarping G, Bellander T, Mathiasson L. 1986. Determination of piperazine in working atmosphere and in human-urine using derivatization and capillary gas-chromatography with nitrogen-selective and mass-selective detection [J].Journal of Chromatography, 370: 245–258.

Sorooshian A, Murphy S N, Hersey S, et al. 2008. Comprehensive airborne characterization of aerosol from a major bovine source [J].Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 8: 5489–5520.

Spector A. 2000. Review: Oxidative stress and disease[J].Journal of Ocular Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 16: 193–201.

Srogi K. 2007. Monitoring of environmental exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: A review [J].Environmental Chemistry Letters, 5: 169–195.

Sunil V R, Laumbach R J, Patel K J, et al. 2007. Pulmonary effects of inhaled limonene ozone reaction products in elderly rats [J].Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 222: 211–220.

Thurston G D, Ahn J, Cromar K R, et al. 2016. Ambient particulate matter air pollution exposure and mortality in the NIH-AARP diet and health cohort [J].Environmental Health Perspectives,124(4): 484–490.

Turpin B J, Huntzicker J J. 1995. Identification of secondary organic aerosol episodes and quantitation of primary and secondary organic aerosol concentrations during SCAQS [J].Atmospheric Environment, 29(23): 3527–3544.

US Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). 1997. Compendium of methods for the determination of toxic organic compounds in ambient air, method to-13a: Determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in ambient air using gas chromatography/ mass spectrometry (GC / MS) [M]. Washington DC: US Environmental Protection Agency.

Utsunomiya S, Jensen K A, Keeler G J, et al. 2004. Direct identi fi cation of trace metals in fi ne and ultra fi ne particles in the Detroit urban atmosphere [J].Environmental Science & Technology, 38(8): 2289–2297.

Verma V, Fang T, Xu L, et al. 2015. Organic aerosols associated with the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by water-soluble PM2.5[J].Environmental Science & Technology, 49(7): 4646–4656.

Wang W, Jariyasopit N, Schrlau J, et al. 2011. Concentration and photochemistry of PAHs, NPAHs, and OPAHs and toxicity of PM2.5during the Beijing Olympic Games [J].Environmental Science & Technology, 45(16): 6887–6895.

Wei Y, Han I K, Hu M, et al. 2010. Personal exposure to particulate PAHs and anthraquinone and oxidative DNA damages in humans [J].Chemosphere, 81(10): 1280–1285.

Weyand E H, Bevan D R. 1986. Benzo[a]pyrene disposition and metabolism in rats following intratracheal instillation [J].Cancer Research, 46: 5655–5661.

Wolkoff P, Clausen P A, Larsen S T, et al. 2012. Airway effects of repeated exposures to ozone-initiated limonene oxidation products as model of indoor air mixtures [J].Toxicology Letters, 209: 166–172.

Xu P, Chen Y, Ye X. 2013. Haze, air pollution, and health in China [J].Lancet, 382: 2067–2067.

Yang X Y, Igarashi K, Tang N, et al. 2010. Indirect and direct acting mutagenicity of diesel, coal and wood burning derived particulates and contribution of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and nitropolycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons [J].Mutation Research / Genetic Toxicology and Environmental Mutagenesis, 695: 29–34.

Zahardis J, Geddes S, Petrucci G A. 2008. The ozonolysis of primary aliphatic amines in fi ne particles [J].Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics, 8: 1181–1194.

Zhou S, Wenger J C. 2013. Kinetics and products of the gasphase reactions of acenaphthene with hydroxyl radicals, nitrate radicals and ozone [J].Atmospheric Environment, 72: 97–104.

Zhu J P, Aikawa B. 2004. Determination of aniline and related mono-aromatic amines in indoor air in selected canadian residences by a modified thermal desorption GC /MS method [J].Environment International, 30(2): 135–143.

Formation and toxicological effect of secondary organic aerosols

CAO Junji1,2, LI Jianjun1,3

(1. Institute of Earth Environment, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Xi’an 710061, China; 2. Key Laboratory of Aerosol Chemistry and Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Xi’an 710061, China; 3. State Key Laboratory of Loess and Quaternary Geology, Xi’an 710061, China)

Background, aim, and scopeAlong with the rapid development of Chinese economy, pollutants derived from increasing usage of fossil fuels and biofuels, as well as emissions from waste incineration and dust have been causing serious air pollution problems in many areas of China. Particular matter (PM), especially anthropogenic aerosols, emitted from various sources may alter regional atmospheric stability, and are of significant impact on climate change and human health. Comparing with PM10(aerodynamic diameter ≤10 μm), fi ne particle (PM2.5, aerodynamic diameter ≤2.5 μm) do more damage to human health. Organic matter (OM), an important chemical composition of fi ne particle, takes 20%—90% of the fi ne particles, has a signi fi cant impact on air pollution and haze event which is happening in China, and has become a frontier of atmospheric chemistry research area. Consisting with many toxic compounds, such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), organic amines and so on, organic aerosol is harmful for human health. Many in-vitro and invito studies of biological toxicity were focused on the primary particulate matters emitted directly from the pollution sources, however, attention for the formation and toxicity of secondary organic aerosols (SOA) are really scarce and therefore urgent.Materials and methodsTaking PAHs, amines, and biogenicterpenes as examples, in order to improve the understanding on health damage of SOA pollution, this article brie fl y reviewed the formation and bio-toxicity effects of speci fi c group of SOA, and focused on the rising toxicity of the products comparing with their parent compounds.Results(1) Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). Because of the mutagenic, teratogenic and carcinogenic properties, PAHs has focused a great deal of attention from scienti fi c researchers and is considered as one of the most important organic pollutants in the atmosphere. Parent PAHs in the aerosols can undergo a photo-oxidation or nitration reaction with gas oxidants in the air to form oxygenated-PAHs (OPAHs) or nitrated-PAHs (NPAHs), and thus the toxicity and health hazard are enhanced. Parent PAHs and their derivatives can absorb light energy to reach the photo-excited states, and then react with molecular oxygen, medium, and coexisting chemicals to produce reactive oxygen species (ROS) and other reactive intermediates, which can induce lipid peroxidation and DNA damage. (2) Amine: Organic amines are derivatives of ammonia in which one or more of the hydrogen atoms replaced by an alkyl or aryl group. They are strong alkaline compounds and play a very important role on secondary aerosols formation. The gaseous aliphatic amines can undergo rapid acid-base reactions to form salt particles in the presence of atmospheric acids (such as HCl, HNO3, H2SO4). Other multiphase reactions of amines include carbonyl-amine interaction and particle-phase oxidation reactions. Particulate alkyl amine can also react with nitrite to form carcinogenic nitrosamine. All these secondary products have signi fi cantly adverse effects on human health, such as skin allergy, respiratory diseases, and cancers etc., and thus would alter the biological effect of aerosols in the atmosphere in return. (3) Terpenes: Terpenes is one of the most important biogenic volatile organic compounds (BVOCs) in the atmosphere. In indoor environment, terpenes can be easily emitted from many consumer products such as furnitures or clothes. On the other hand, some gaseous oxidants like ozone and NOxcan also present in the indoor air because of the in fi ltration from outdoor environment or emission by some of fi ce and consumer equipment. Thus, the indoor health effect of secondary organic aerosol formation of terpenes with other gaseous oxidants is a popular issue in recent researches. Some of the gaseous products formed are irritating to biological tissues, while the condensed-phase products have received attention due to their contribution to ambient fine particulate matter and its respective health signi fi cance. Although the biochemical mechanism of terpenes to human body remains unclear, but nearly all the related studies can prove that the secondary products of terpenes have some harmful effect to human epidermis or respiratory system.DiscussionAt present, many researches were focused on the bio-toxicity effects of fi ne particles in the atmosphere, however, rare studies referred to the toxicity change of secondary organic aerosols formation in the atmosphere.ConclusionsMore speci fi c areas in which improvements and advances could be made for toxicological studies of secondary organic aerosols in the atmosphere in the future.Recommendations and perspectives(1) Comprehensive study combining the chemical and bio-toxicity properties of secondary organic aerosols; (2) Research on bio-toxicity of secondary organic aerosols from speci fi c pollution sources.

secondary organic aerosols (SOA); toxicity; polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs); amines; terpenes

CAO Junji, E-mail: cao@loess.llqg.ac.cn

10.7515/JEE201605001

2016-06-02;录用日期:2016-08-02

Received Date:2016-06-02;Accepted Date:2016-08-02

中国科学院战略先导性专项(XDB05000000)

Foundation Item:Strategic Pilot Project of Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB05000000)

曹军骥,E-mail: cao@loess.llqg.ac.cn