Just Dance

The politics of individualism in Chinese modern dance

現代舞在中国

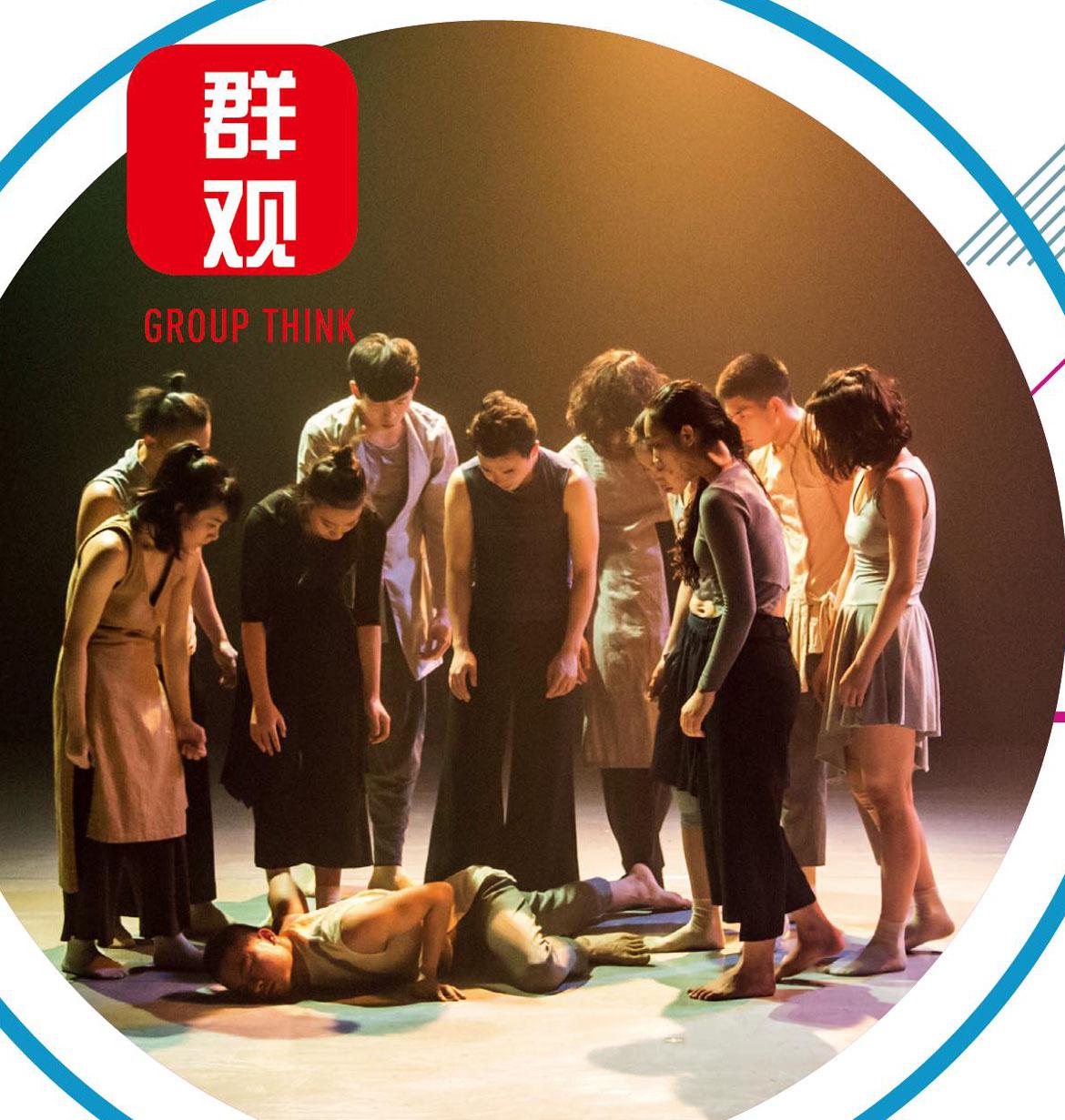

The ninth annual Beijing Dance Festival, which took place this summer from July 14 to July 26, closed with choreographer Zhang Xuefengs meditative exploration of fear, fascination, and the struggle for self-redemption before the worlds end. Performed by Chinas oldest contemporary dance troupe, the Guangdong Modern Dance Company (GMDC), Zhangs piece, “Days of Heaven”, brings out an emphasis on the individuals emotional struggle that strikes a chord with the experiences of modern and contemporary dance artists who work in China today.

An art form born out of a rebellion against classical ballet and against Victorian strictures about the human body, it is perhaps not surprising that modern dances rising popularity in China tends to be discussed in political terms such as freedom, expression, and the importation of artistic trends from the West. We have a surprisingly complete record of how American art critics, at least, regarded the political and cultural implications of modern dances entry into China during the reform and opening-up period. Disregarding Qing noblewoman Yu Rongling—who studied with Isadora Duncan in 1902 and performed for Empress Dowager Cixi—and the socio-realistic, 1930s anti-war productions, Chinas “Father of New Dance” Wang Xiaobang and his German-influenced modern dance academy in Shanghai, Chinas current modern dance tradition can be traced back to the 1980s. This came a decade after the Cultural Revolution, when only propagandistic “model ballets” were allowed to be staged anywhere in China.

As the story goes, Guangdong Dance Academy director Yang Meiqi, whose school was best known for training folk dancers, went to the American Dance Festival in 1986 and was inspired to start a modern dance program at her school. She invited American dancers to teach it, and the government created the GMDC to give jobs to the graduates. The New York Times, spotting an apt metaphor for Chinas tentative embrace of the international system, checked in with the Guangdong cohorts story several times in the next decade and left snapshots of vintage American views on Chinese society. An austere rehearsal studio “exudes an aura of hardship, stoically endured,” noted a report from 1988. A 1990 report celebrating the founding of the GMDC made cryptic reference to Chinas recent “political twists and turns” and credited the dancers for demonstrating “the oldest Chinese dance form: the individuals pirouettes around the authorities in the struggle for free expression.”

Willy Tsao, the GMDCs artistic director, agrees that the essence of modern dance is freedom, but he wants to liberate the definition of freedom from political movements and “the Western point of view of whats provocative, whats critical,” he toldTWOC. The irony of politicizing modern dance in China is not lost on Tsao, who noted that this was exactly the Communist treatment of art: “When New China was established in 1949, art was used as a tool to educate people to be more patriotic and optimistic of the future. These days, there is much more freedom in the theater, [which is] doing what the artist wants to do.”

There are still lines that dancers cannot cross in China: nudity is one, as well as commentary on contentious regional issues. Tsao diplomatically calls his early relationship with the authorities in the Guangzhou school days as “discussions and quarrels”. “The government knows me, they know artists are trying express themselves and not promoting different values,” Tsao says.

This allowed him to focus on what he wanted to do, which was to give artists a platform to create. “If they want to do something provocative theyre free to do that, if they want to do something personal thats perfectly okay. Its up to them,” Tsao says.

These days, institutional and cultural hurdles are still the norm for modern and contemporary dancers in China—“contemporary” being an ill-defined dance genre that mixes modern techniques with ballet and other art forms. Modern dance education largely remains limited to individual courses rather than full curriculums at universities and dance schools, though according to Tsao the courses are extremely popular. Audiences and young dancers new to the genre are often unnerved by its concepts, such as broken lines and perspectives, intimate body contact, and almost total focus on the body itself as the tool of expression.

To thrive, dancers unlearn attitudes ingrained by society and the education system in China, according to Tsao, which is “to hide their body, be polite to each other, put on a lot of ‘face—modern dance gets them to use their bodies in totally different ways from before.” However, they also go through a constant and more universal battle with their own selves to figure out what they wish to express, then represent it, over and over, to the public authentically and without mediation. “Its very daring, very personal…all they see is your body, your total self in front of others,” Tsao said.

Today, Chinas modern dance companies tour worldwide and perform alongside fellow artists from around the world at dance festivals. This years Beijing Dance Festival had around 200 participants from four continents. In 2008, the Beijing LDTX Theatre became Chinas first independent modern dance company, not registered under any government institute, also with Tsao as its director.

Performances cover themes that range from the global to the deeply personal. The Beijing Dance Theatres early piece, “Martlet”, depicted life in Beijing; its first international tour featured “Haze,” a representation of both smog the 2009 environmental crisis. Tao Dance Theatre, also of Beijing, won rave reviews from its London debut in 2014 with a more abstract piece aimed, according to The Telegraph, at making the audience “observe movement unencumbered by meaning”.

Zhangs “Days of Heaven” also straddles the space between the abstract and personal, with the final emphasis how modern dance is both at once. Costumed in mostly greys and browns, with a spartan set consisting of a single doorway and a light resembling a solar eclipse, the body of the dancer depicts contrasting stages of emotion before the cataclysm. Movements shift from meditative to frantic; multiple actions on stage take place at the same time on different planes and with contrasting lines, highlighting the diversity of each persons expression.

“My main idea for the piece is: on the last day of the world, what would you do? Feel? Who would you be with?” Zhang told the audience in the post-performance Q&A. “[With] a very simple setting, you can see these individuals struggle with the end differently, looking for some sort of salvation all at the same time but in their own way.” Its also a metaphor for the journey of Chinas modern dancers as a whole.