可持续发展的奥运会?都灵2006年冬奥会的背景和遗产

古斯塔沃·安布罗尼西,莫罗·贝尔塔,米凯利·博尼诺/Gustavo Ambrosini, Mauro Berta, Michele Bonino

王欣欣 译/Translated by WANG Xinxin

可持续发展的奥运会?都灵2006年冬奥会的背景和遗产

Sustainable Olympics? Background and Legacy of the Torino 2006 Winter Olympic Games

古斯塔沃·安布罗尼西,莫罗·贝尔塔,米凯利·博尼诺/Gustavo Ambrosini, Mauro Berta, Michele Bonino

王欣欣 译/Translated by WANG Xinxin

1 “高山都市”的背景

无论是成为2006年冬季奥林匹克运动会的候选城市,还是之后作为主办城市,对都灵来说都是无以伦比的体验。联系到这座城市的历史背景,以及自1990年代早期开始的城市整体规划所带来的城市框架的巨大转变,这些经历与当地城市政策的关联能够得到更完整的理解。

自1998年申办初期,都灵作为候选城市,其最重要的特色应该就是它长久以来与山地的关系,包括独特的地理因素和历史原因两个方面。作为横跨西阿尔卑斯山脉两端的古老萨伏依公国的故都,都灵保持了城市结构形态与周边山脉的密切关系,它所在的大都市平原被周边山脉包围。从市中心望去,山顶的景象清晰可见。因此,山脉不单单是离这座城市很“近”,而是某种程度上就在城市之“中”,是都市空间必不可少的一部分。山景成了诸多街道和林荫大道的背景,其中有一些甚至是从市中心内部即可见的地标。许多当地的活动和机构都围绕着阿尔卑斯山脉展开,比如,建于1874年的国家山地博物馆,就是这座城市长久以来的“高山使命”的例证,当然更有力的证据是早在1863年成立于都灵的意大利登山俱乐部(Alpine Club of Italy,简称CAI)。

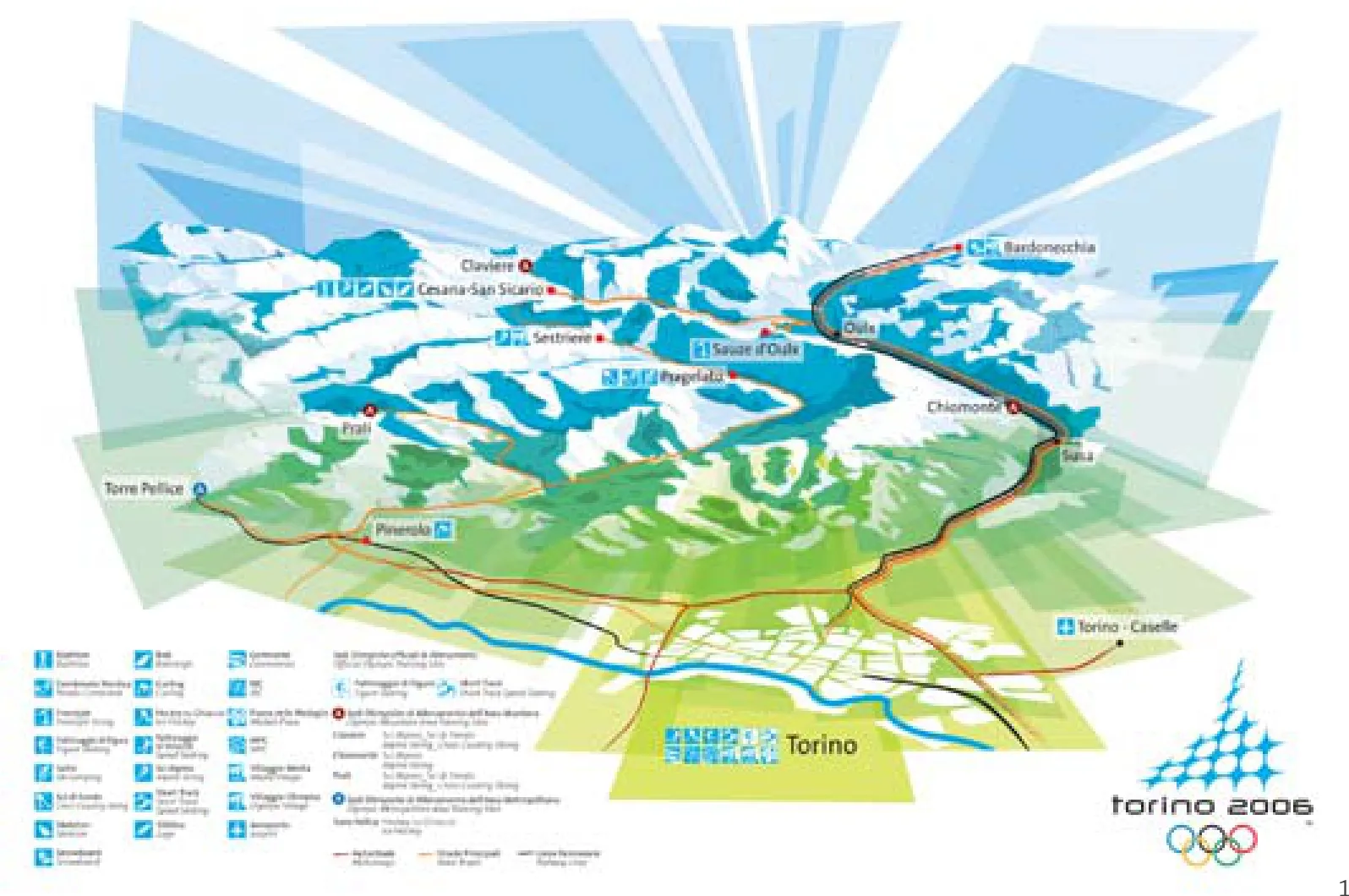

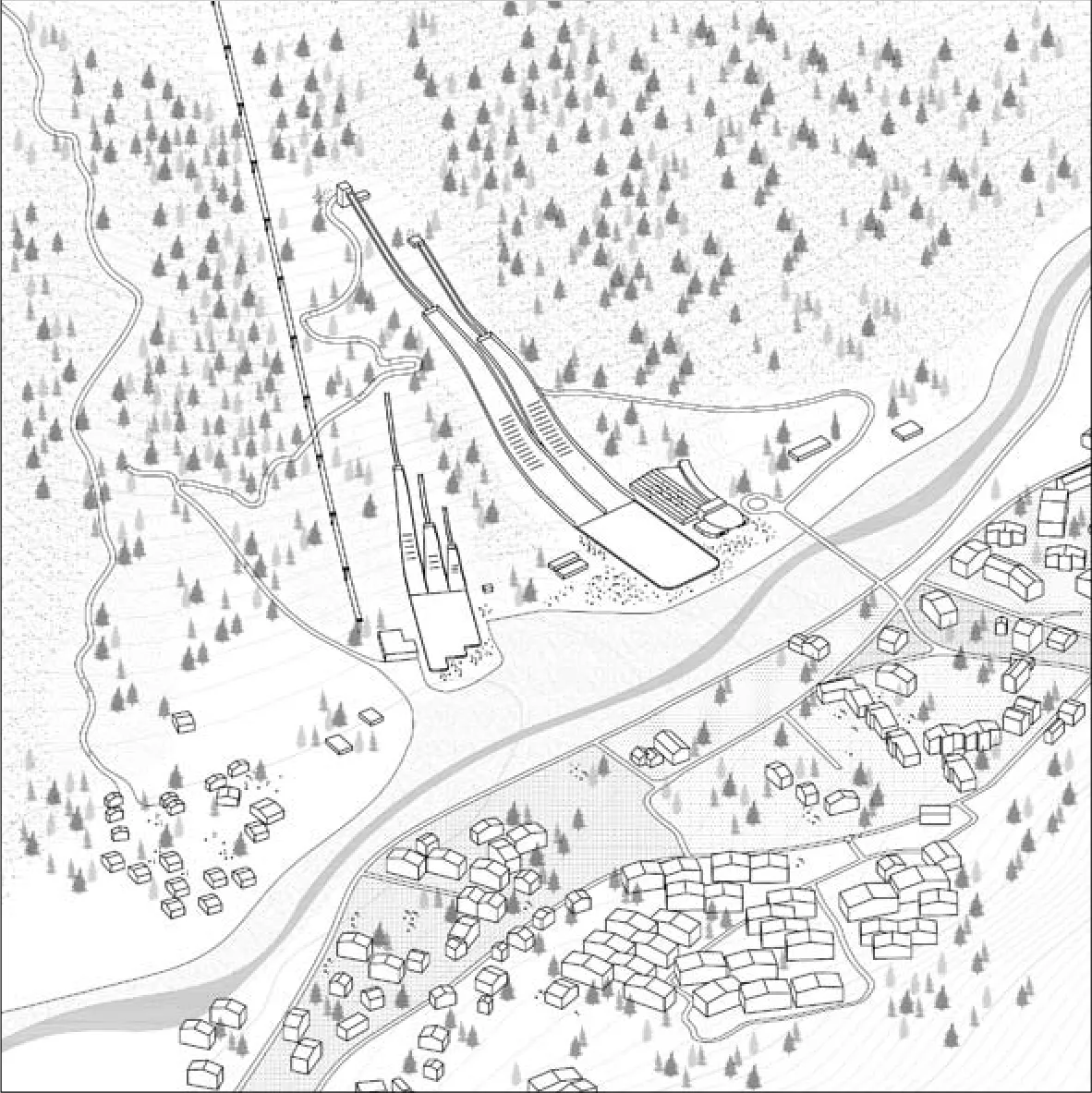

都灵2006冬奥会(图1)并非赋予了这片土地一个崭新的旅游产业,而是为这座城市提供了一次在全球范围内提升“高山都市”形象的机会。都灵通过改善位于山地和城市之间的已有体育休闲设施网络将其变为现实。

2 处于大城市视野中的奥运场所

从一开始,奥林匹克工程的整体区域性策略就十分明确,它由两个对立的选项组成,可大体划分为位于山区的“雪上”项目和位于市区的“冰上”项目。因而最“重”的新建筑,也是占据了更多资金的工程,都集中于市区。位于山区的主要投资和建设早在1997年的高山滑雪世界锦标赛之际就已完成,因此对于山区,策略的关键在于提升和改进已有设施,这其中包括了冬奥会中用于跳台滑雪项目的普拉格拉托体育场和塞萨纳—帕里奥体育场的有舵雪橇轨道。

第一轮竞选提案中,位于城市北部的康帝纳萨区被指定为市区竞赛场所的核心,考虑到它靠近高速公路和便捷抵达当地机场的地理位置,并且距离最初被指定为主要庆典举办场所的德尔·阿尔卑体育馆(现在的尤文图斯体育馆)很近。只是后来,计划彻底改变,都灵奥组委决定将城市焦点从北部边界移动到“灵格托轴”。这其实是都市规划中一条新的“中央脊柱”的一部分,最终的整体规划对此作了定义。新提案中,位于市区的奥林匹克场馆的地理位置全部重新规划,相比之前远离现实城市动态而独立的新建场馆组团的构思,改成将竞赛、训练、住宿和服务设施集为一体的紧凑型设计,分布于城市中主要的转型地区,与周边社区相联系。因此,奥林匹克大家庭城市生活的新焦点变成了军事广场附近广阔的绿色区域,前市级体育馆成为新的庆典场所,面对奥运火炬塔。

这个转变可能是奥林匹克工程总体规划中最显著的方面。鉴于它与更大的城市视野之间的密切关系,而城市转型实现在即,这个转变可以被看作整个项目运行可持续发展的一个重要因素。

尽管整体框架看起来具有连续性,单个项目在运行效果上仍然存在差异。尝试理解项目之间的共同特性就显得饶有趣味。

3 场馆建筑:形态学分类的尝试

奥林匹克场馆和设施通常是依据不同元素来分类的,例如:功能、规模等。基于具体的城市设计问题,在这里我们设想一个不同的视角:设计的关注点在于新设施与其所处环境之间的关系。

3.1 改善城市结构的新公共空间

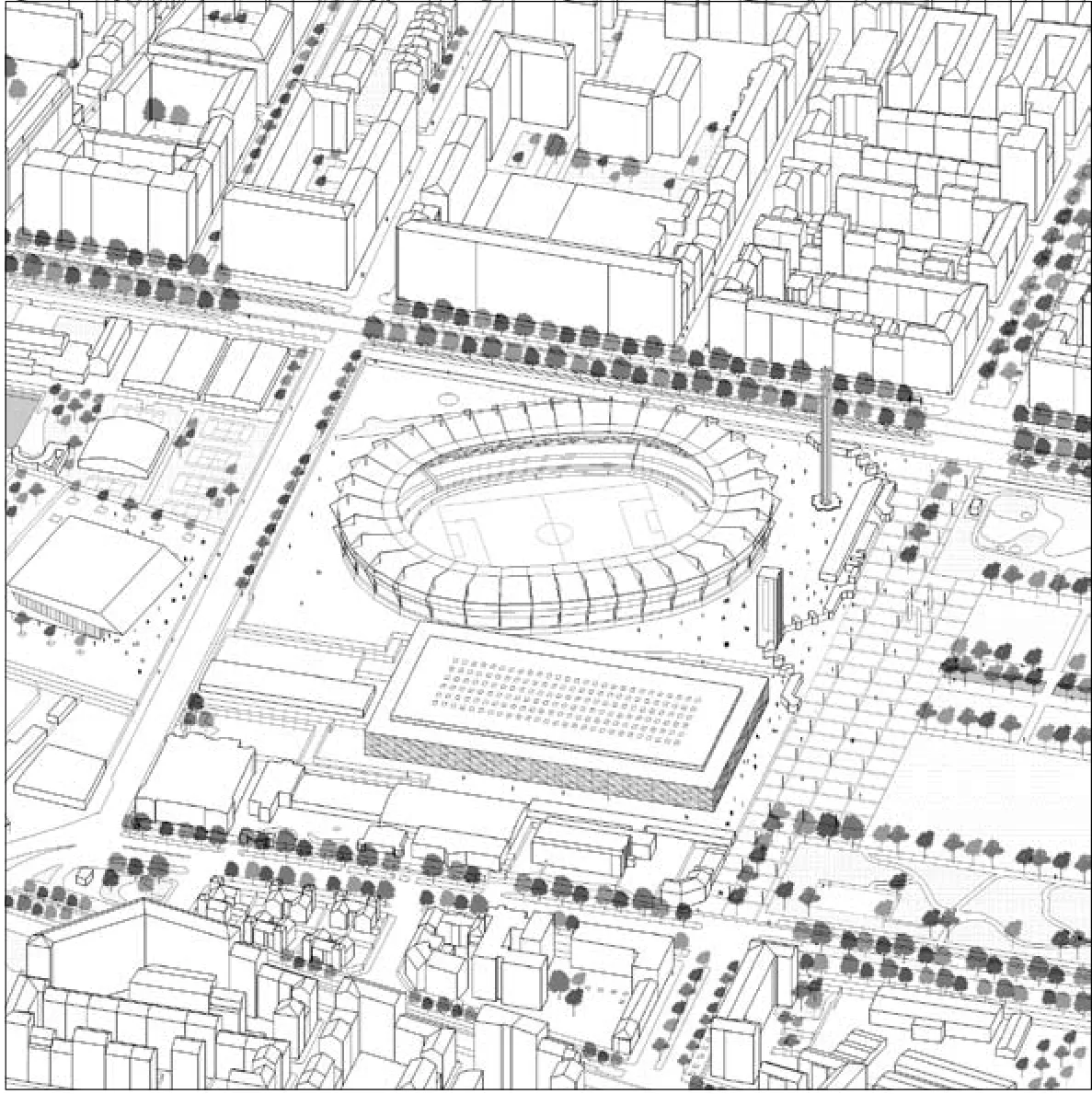

对始建于1930年代运动场馆组团的翻新是尤为突出的案例,这里主要指前市级体育馆和新奥林匹克冰球竞技场(图2)。成功的关键在于对广阔的开放公共空间进行重新利用,将周边街道的一部分转变为一个大型步行区域,以及重新设计军事广场的大面积绿化区。这两座大型建筑在公园大草坪的两侧相傍而立,为中间的高密度区域提供了新的公共空间。奥林匹克(冰球)竞技场配备了可移动立柱和地板,为内部空间分布和功能的改变提供了可能性,适用于不同用途,例如,冰上运动、室内运动、音乐会、演出和展览。另一方面,新建的游泳中心使得设施的全面性得以完善,尽管步行区域的合理重建尚未实现。

相似的成功体现在成为了冰上运动训练场所的塔佐利宫殿的建筑上,它所在的位置与重建计划中的科尔索—塔佐利轴线相一致,并且为配套设施不够完善的工薪阶级区域提供了体育运动和室内活动服务设施。

这些案例展示了大型建筑物与开放空间或城市结构相融合的可能性。

3.2 独立“对象”

这恐怕是超大型体育建筑的一个主要缺点,当它们独立存在的时候,很难建立人类尺度与生机勃勃的城市肌理之间的关系,而自相矛盾的是,它们的复杂程度与其巨大的体量并不相称——不能够确保诸多赛事在单一建筑内无限扩张,以此来重新创造城市的活力。这个现象在雷姆·库哈斯和布鲁斯·毛的著作《S, M, L, XL》中得到了诠释。

例如,举办“意大利 '61”展览的主楼薇拉宫,经过翻修以后,加重了原本就存在的疏离感:玻璃外立面被拆除,取而代之的是一些红色的体量,与其上的混凝土拱顶脱离开来,显得毫不相干,而且还因为流失了原来大面积的室内空间而让人不由得产生怀旧之情。

1 都灵2006年冬奥会总体布局示意/Diagram for the Torino 2006

1 The background of an "Alpine metropolis"

The candidacy and the designation as the host city of the 2006 Winter Olympic Games has been a significant experience for Torino. The relevance to local urban policies can be completely understood with regards to the historical background of the city and, most of all, in the general framework of huge transformations that have been driven by the general masterplan of the city, beginning the early 1990s.

Since the very beginning of the bid in 1998, it was clear that one of the most important features of Torino's candidacy should have been its longstanding relationship with the mountains, which is grounded both on geographical peculiarities and historical reasons. Once the capital of the former Savoy's "Kingdom of Sardinia", which once spanned both sides of the western Alpine chain, Torino preserves in the morphology of its urban fabric a close connection with the surrounding mountains, which in turn encloses the metropolitan plain. The mountain tops that are visible from the city centre thus are not simply "near" to the city, but most of all they are an essential – and somehow "internal" – part of the urban space itself. They are a backdrop of many streets and boulevards; some of them are landmarks visible even from parts of the city centre. A number of local activities and institutions have focused on the Alps, for example, the National Museum of Mountain, founded in 1874, are a proof of the longterm alpine calling of the city, as well as the most important evidence, most likely the birth of the Alpine Club of Italy (CAI), founded in Torino in 1863.

Torino 2006 (fig.1) was not an event that spurred a new tourist vocation of the territory, but instead it was an opportunity to promote worldwide the image of an "Alpine metropolis", by improving an already existing network of sports and leisure facilities, distributed between the mountains and the city.

2 The Olympic venues as a tile of a larger urban vision

The overall territorial strategy for the Olympic works was clearly defined since the beginning, with two opposing strategies, which can be roughly identified by the separation between "snow" activities, located in the mountain venues, and "ice" activities, placed within the city. As a consequence the most "heavy" new structures, and the greater amount of funding, were concentrated in the urban area. Meanwhile, in the mountain venues, major investments had been already been spent for the Alpine Ski World Championships of 1997. Therefore, the strategy was aimed at the improvement and enhancement of these existing facilities, with the additional realization of some specific sports facilities, such as the ski jumps in Pragelato and the bobsleigh track in Cesana-Pariol.

In the first bid proposal, an area in the northern city known as Continassa was chosen as the core of the urban competition venues, thanks to its position- close to the motorway and easily accessible from the local airport – and most importantly to its proximity to DelleAlpi Stadium (now Juventus Stadium). The stadium was originally designated as the site for the main celebrations. Only later, the program changed radically and the Organizing Committee (TOROC) decided to move the urban focal point from the northern edge of the city to the "Lingotto axis", which is part of the new "Central backbone" of the city, as defined in the previous Torino general plan. The geography of the Olympic venues in the metropolitan area has been thus completely reorganized in this progress, passing from an idea of an almost independent sports compound, far from the real city dynamics, to a very compact and integrated mix of competition, training, housing, and service facilities, distributed along the main transformational areas of the city and in relation to surrounding neighborhoods. Consequently the new focus of the Olympics' urban life became the wide green area of Piazza d'Armi, where the former Municipal Stadium was transformed into the new celebrations site, facing the Olympic cauldron.

This change is probably the most notable aspect of the masterplan of the Olympic works, and, since it is strongly related with a larger urban vision that is still ongoing, it could be seen an important key element of the sustainability of the whole operation.

Although the general framework appears consistent, the outcomes of single operations show different levels of achievement and it appears interesting to try to recognize some common features of them.

3 The architecture of the venues: an attempt of a morphological categorization

The Olympic venues and facilities are usually categorized according to different elements, such as function, size, etc. Here we assume a different viewpoint, based on a specific urban design issue; the aim is to propose a critical look focused on the relationships that the new facilities establish with their contexts.

3.1 New public spaces improving urban fabrics

The case of the renovation of the sports compound created in the 1930s, focusing on the former Municipal Stadium and on the new Olympic Ice Hockey Arena, is particularly significant (fig.2). The key of its success was probably the opportunity to incorporate the adjacent public space, transforming a portion of the fronting avenue into a large pedestrian zone and redesigning the large landscaped area of the Piazza d'Armi. The two big volumes mirror themselves in the large lawns of the park, providing a new public amenity in the middle of a high density district. The Olympic Arena is equipped with mobile stands and movable floors that allow the modification of its internal organization and function, and it is adaptable for different uses such as ice sports, indoor sports, concerts, shows, or exhibitions. Next to the arena, a new Swimming Centre complements the facilities offered, although it still awaits a proper renovation of its pedestrian area.

A similar success has been achieved by the Tazzoli Palace. Used for ice sports training, its architecture is coherent with the renovation program of the Corso Tazzoli axis, and provides a point of reference for sports and indoor events within a working class district under-supplied with services.

These case studies show the possibility of conciliating the scale of the large buildings with of the open spaces or the surrounding urban fabric.

3.2 Stand-alone "objects"

This is probably the main drawback of large sport buildings: when left alone, they are too big to establish human scaled relationships with lively urban tissues but, paradoxically, are not complex enough to gain the status of "bigness", meaning the promiscuous proliferation of events in a single large container could recreate the city's vitality itself, as was portrayed by Rem Koolhaas and Bruce Mau in their well-known book, S, M, L, XL.

In the same way, the pre-existing loneliness of "Italia '61" Exhibition main building – the Palazzo Vela – has been in some way stressed by renovation work: the demolition of the glass facades and the construction of some red volumes detached by the concrete vault produce a feeling of extraneousness (but create a nostalgia for having lost an extraordinary indoor spatiality under the dome).

用作速滑冰道的奥沃尔室内体育场也有着类似的命运,现在它只是沉寂于灵格托旧工厂和铁路之间一个廖无人迹的低地。

3.3 居住者的建筑

奥运村面临的最大挑战就是建立与城市肌理相结合的真正意义上的居民区:项目将居住区的实施和完成设想置于一个棕地(已开发但处于闲置的地区)发展过程的框架中。

政府和私有运营者实施的设计方案聚焦于居住环境的灵活度,在第一阶段满足运动员村和媒体村的需求,之后作为集体房屋或者投入地产市场:即作为学生宿舍单元、住宿单元和家庭住宅。为了最大限度保证后期布局的可优化性,在设计早期就对植被和结构进行了研究。

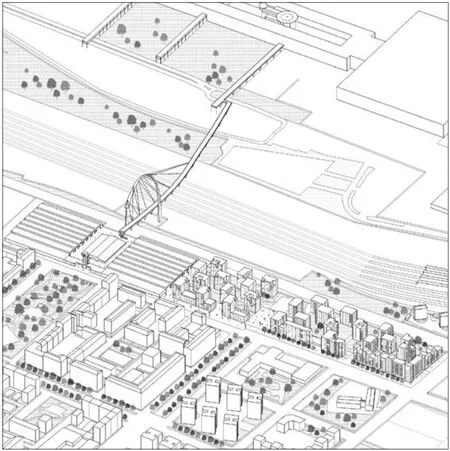

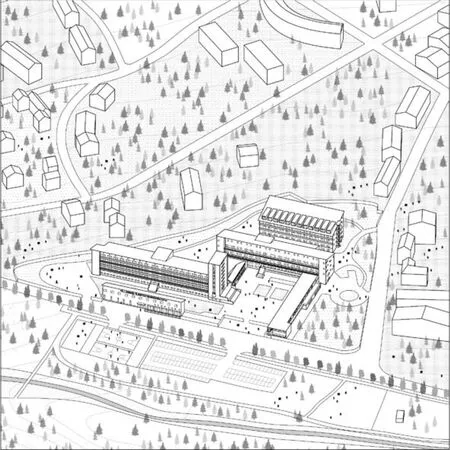

在众多对城市的干预之中,两个大范围的新区浮现出来:建于1930年代初的中央果蔬市场的奥运村(图3),以及建于钢铁车间“斯皮纳3号”旧址的媒体村。在城市之外,山区运动员村地处苏萨谷的一个同样始建于1930年代的日光浴场度假村的旧址,是翻修和再利用成功案例的代表(图4)。

3.4 建筑即表演

奥运会期间,一个被三维立体镜面钢板包裹的钢架矗立在位于市中心的卡斯特罗广场上,看起来就像一个外星物体。勋章广场配备了舞台、剧院、媒体和公众服务设施、通讯及技术物流设备,容纳过9000人次,举办了55场庆典活动以及15次音乐会。它和历史背景毫无联系。它看起来更像是居依·德波在1967年书中所描述的“景观社会”的一次完美实现。然而,这个构筑物作为镜子的角色至关重要:城市在建筑表面中的映像在全球各地的电视上重现,每一次都是独一无二的呈现。媒体对都灵的特色演绎使得人们对这座城市有了一个新的感知,实现了它身份的独特性。

3.5 波浪形的景观

有舵和无舵滑雪轨道、跳台滑雪以及其他相似的场所利用了山脉令人印象深刻的标志性特点。它们的几何形态源于每个竞赛项目的速度规则,尽管赛事场所以曲折蜿蜒的形态融入了景观,但因为其尺度远远大于人类并形成了鲜明的对比,这在夏季尤为突出。这些赛道对原有场地的改变很大,需要景观和环境工程两个专业的介入,涉及地质学、水源管理、土壤科学等等。一系列配套的设施、看台和停车区相应而生,而这些设施是临时的,需要在赛后拆除。

塞萨纳的舵滑雪轨道后来遭到废弃,意味着一个问题亟待解决。普拉格拉托跳台滑雪场在奥运会后重修,在倾斜的山坡上成为了一座“英雄式”的现代建筑(而它距离1930年代建于塞斯特雷的首座建筑并不远),强调了这个区域在冬奥会的身份(图5)。

4 都灵冬奥会的遗赠

在距离都灵冬奥会将近10年后的今天,奥运会引发的转变已经有些模糊不清。每个案例带来的结果都不尽相同,因此很难做一个综合的评价。

那些意在表现强烈典型的奥林匹克形象的建筑,在今天的城市中依然是象征性的地标,其中还有一些和重大的城市重建进程不谋而合。

位于城市和高山村落中的居住设施,命运分为两类。一类是在前期准备阶段就进行了赛后功能和管理规划的项目,基本达到了预期的利用效果;另一类因为后期使用或管理职权没有得到适当的考虑而以失败收尾。

相比之下,竞赛场馆成败的衡量标准则在于赛后是否得到有效利用,或者是否能在成本效益的前提下进行功能的便捷转化。

总之,奥运工程最有趣的方面就是“城市策略”的总体框架,并非被当成一座自主和独立的主题公园,而是与过去几十年彻底改变都灵面貌的城市转变紧密相连。□(鸣谢:轴测图作者法布里齐亚·帕拉尼,萨拉·瑞希亚)

2-5 都灵2006年冬奥会场馆设施轴测图/Axo drawings of Torino 2006 (绘图/Illustrated by Fabrizia Parlani, Sara Ressia)

A similar destiny seems to be shared by the indoor sports stadium for speed skating, the Oval, which is now sunken into a wide no man's land of parking between the former Lingotto factory and the railway.

3.3 Architectures for inhabitants

The main challenge for the Olympic villages was the possibility to create some authentic residential neighbourhoods that are integrated in the urban fabric: the program envisaged the implementation and completion of residential interventions in the framework of a brownfield redevelopment process.

The design strategy followed by public and private operators focused on the flexibility of the dwellings, able to fulfil the athletes and media village requirements in the first phase, and the ability to be reused for either collective housing, residential units for students, accommodation units, or residences for families. The possibility of optimising further adaptations for distribution, plants and infrastructure has been studied since the beginning of the design process.

Among the many interventions within the city, two new districts emerge: the Olympic Village (fig.3), related to the renovation of the General Market (originally built as a market for fruits and vegetables in the 1930s), and the Media Village, built on the former site of Spina 3, a series of iron and steel plants. Outside the city, the mountain Athletes' village was located in the Susa Valley in a former heliotherapic resort also dating from the 1930s, representing a successful case of restoration and reuse (fig.4).

3.4 Architecture as show

During the games, a three-dimensional steel girder covered with reflecting steel panels appeared as an alien object in the city centre's main historic square, the Piazza Castello. The piazza was transformed into Medals Plaza - which included a stage, a theatre, sets, services for the press and the public, and communications and logistics equipment. During the Olympics, the plaza could contain 9000 people, and hosted 55 celebrations and 15 concerts, without assuming any relationship at all with its historic context. It seemed to be a perfect materialisation of the "society of the spectacle", described by Guy Debord in his 1967 book. However, it had a great importance as a mirror: the city seen from that building, and reproduced worldwide via television, would never have been the same; the representation of Torino seen through media offered a new perception of the city, reinforcing its identity.

3.5 Waving forms in the landscape

The bobsleigh and luge track, the ski jumps, and other similar venues drew on the mountains impressive features. Their geometries derived from the rules of every discipline, and though they fit into the landscape with their meandering lines, they possess a wider scale than the human one, which also greatly contrasts with it, especially in the summertime. They have modified a significant portion of these sites, requiring interventions both of landscaping and environmental engineering, the latter of which involves geology, water management, and soil science. They brought with themselves a number of facilities, tribunes, parking areas, that were required to be temporary and were removed after the events.

The Cesana bobsleigh track has suffered from disuse, representing a problem that needs to be solved. The Pragelato ski jumps were renovated after the Games, standing on the slope as "heroic" modern architecture (not so far from the architecture of the 1930s in Sestriere), underlining the winter sport identity of this part of the valley (fig.5).

4 What could be learned from the legacy of Torino Olympics?

Almost 10 years after the event, an overall glance of the Olympic transformations returns a slightly blurred image. The results greatly differ from case to case, and a comprehensive opinion is still difficult to be expressed.

Several of the most iconic buildings, meant to create a strong and recognizable image of the Olympics, still remain today symbolic places of the city, and some of these have coincided with important urban regeneration processes.

The residential facilities within the city and the alpine villages obtained the envisaged effects only when post-event functions and management had been previously planned during the preparation stages, but failed when either the uses or the managing authorities had not been properly considered.

The success of the competition venues therefore depended on the possibility of being effectively utilized after the event for their original use, or instead being easily converted into other costeffective purposes.

Above all, the most interesting aspect of the Olympic works is the general framework of an "urban strategy", not conceived as an autonomous and independent thematic park, but rather closely connected with the transformations that have been changing the face of Torino in the past few decades.□ (Acknowledgements: the axonometric drawings that illustrate this article are by Fabrizia Parlani and Sara Ressia. )

都灵理工大学建筑设计系

2015-08-15