Single-blind, randomized controlled trial of effectiveness of Naikan therapy as an adjunctive treatment for schizophrenia over a one-year follow-up period

Hong ZHANG, Chenhu LI*, Liyu ZHAO, Guilai ZHAN

•Original research article•

Single-blind, randomized controlled trial of effectiveness of Naikan therapy as an adjunctive treatment for schizophrenia over a one-year follow-up period

Hong ZHANG, Chenhu LI*, Liyu ZHAO, Guilai ZHAN

Naikan therapy; schizophrenia; relapse; social functioning; randomized controlled trial; China

1. Background

Schizophrenia, a chronic mental illness with frequent episodes of severe psychotic symptoms, is a disabling condition that seriously impairs social functioning and usually has a poor prognosis. After the first acute episode approximately 50% of patients have a recurrence within one year and approximately 85%of patients have a recurrence within 5 years.[1]This high recurrence rate results in a substantial social and financial burden for the individual, the family,and society at large. Other studies report that costs incurred by individuals who relapse within one year of their first episode are three- to four-fold higher than those incurred by individuals who do not relapse.[2]This highlights the importance of improving the social functioning and decreasing the relapse rate after an acute episode of illness. A variety of approaches have been tried, typically involving the use of antipsychotic medication (to control positive psychotic symptoms)with adjunctive treatments such as psychotherapy,community-based interventions, family therapy, and so forth.[3]One such adjunctive treatment for schizophrenia is Naikan therapy, a structured method of self-ref l ection which originated in Japan,[4]that has been shown to produce short-term improvements in treatment adherence and social function among patients with schizophrenia in China.[5-7]

This paper reports on a randomized controlled trial of adjunctive treatment of schizophrenia with Naikan therapy that assessed the psychiatric symptoms, social functioning, and relapse rate of participants over a oneyear follow-up period.

2. Methods

2.1 Subjects

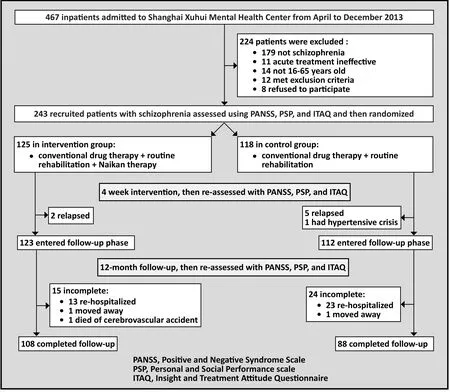

As shown in Figure 1, among the 467 patients treated as inpatients at the Shanghai Xuhui Mental Health Centerfrom April 2013 to December 2013 there were 243 who met the following inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study: a) meeting the diagnostic criteria of schizophrenia specified in the International Classification of Diseases-10, (ICD-10);[8]b) 18-60 years of age; c)junior high school education or higher; d) inpatient treatment results in a ≥50% drop in the total score of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)[9]or a total PANSS score <60 within 8 weeks of admission; d)negative symptoms, agitation, and obsessive compulsive symptoms are not severe enough to interfere with study participation; e) no other mental disorder, organic brain disorder, or substance use disorder; f) no severe medical illness; g) not pregnant or breast-feeding; h) is not participating in any other clinical trial; and i) both the patient and the patient’s guardian provide written informed consent.

Figure 1. Flowchart of the study

The PANSS was assessed on all potential participants with schizophrenia every week after admission for eight weeks and the individual was enrolled as soon as the total PANSS score had decreased >50% from baseline or was<60. The 243 enrolled patients were randomly assigned to the intervention group (conventional antipsychotic medication and rehabilitation therapy + Naikan therapy)or the control group (conventional antipsychotic medication and rehabilitation therapy) using a random number generating function in the SPSS software.

As shown in Figure 1, during the 4-week active treatment phase of the study 2 patients who relapsed dropped out of the intervention group while 5 patients who relapsed and one who experienced a hypertensive crisis dropped out of the control group. All participants were hospitalized during this active treatment phase.This left 123 patients in the intervention group and 111 in the control group who were then followed-up one year later. The patients remained in hospital for varying lengths of time after the end of the active treatment(often determined by fi nancial or family issues, not by the clinical status of the patient), but all patients had been discharged and were evaluated as outpatients at the time of the one-year follow-up assessment.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Shanghai Xuhui Mental Health Center.

2.2 Intervention

All enrolled patients were treated with standard doses of atypical antipsychotic medication by inpatient clinicians who were blind to their group assignment. The dosage employed at the time of enrollment (by which time the PANSS had decreased >50% from baseline or the total PANSS score was <60) was maintained throughout the one-month intervention; the dosage was subsequently adjusted by the treating clinician as needed during the 12-month follow-up period. All enrolled patients also received routine rehabilitation therapy for inpatients,which included music therapy, biofeedback, cognitive skills training, and so forth. Inpatients in the intervention group received similar treatment except for the addition of Naikan therapy. After discharge from the hospital all enrolled patients were seen monthly in the hospital outpatient department by their treating clinician.

Naikan therapy,[4,5]provided in 20 two-hour sessions over a 4-week period, was conducted by three therapists who had personally undergone Naikan therapy and had received Naikan therapy training in Osaka, Japan.Each session started with 15 minutes of consultation with the patient in which the results of the previous session were discussed and instructions and suggestions for the current session were provided. After the consultation, the patient completed the recommended thought exercises while seated alone quietly in a room specifically designed for Naikan therapy that was separated into several individual cubicles by wooden panels. The therapy involves systematically considering and evaluating prior experiences from four perspectives:three main themes, chronological stages, objects(i.e., individuals), and procedures (i.e., assessing their emotional responses). Patients consider three themes based on their own experiences: ‘what others did for me’, ‘what I did for others’, and ‘what troubles I have caused to others’. They then review the recalled life events in chronological order both from the perspective of other participants in the events and from their own perspective. This process is repeated for a range of acquaintances, from the closest (e.g., parents, children,spouse) to the most distant (e.g., those whom the individual dislikes the most). At each step in the process the patient is encouraged to systematically analyze his or her emotional responses such as feelings of regret,guilt, or gratitude, and the willingness to make amends.

2.3 Instruments

The Chinese version of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)[9,10]was used to evaluate the severity of psychotic symptoms. It consists of four subscales with 33 items and includes five factors:positive, negative, cognitive, excitatory, and anxiety/depression factors. Items are rated 1 to 7 with higher scores representing more severe symptoms.

The Personal and Social Performance scale (PSP)[11]is a single-item clinician rating from 0 to 100 used to evaluate four components of social functioning: a) work and study; b) social relationships; c) self-care; and d)socially disruptive or aggressive behaviors. The score is classified into 4 categories: 71 to 100 indicates no difficulty or minor difficulty; 31 to 70 indicates definite functional defect; and under 30 indicate poor social function requiring active support and close monitoring.

The Insight and Treatment Aゆtude Questionnaire,ITAQ[12]is an interviewer-completed questionnaire with 11 items scored 0 (none), 1 (partial insight), or 2 (definite insight). The range in ITAQ total scores is from 0 to 22, with higher scores representing better insight and greater willingness to adhere to recommended treatment;the inter-rater reliability of the total score among raters participating in this study was fair (Kappa=0.56).

2.4 Evaluation

Four psychiatrists not involved in the treatment of the patients who were blind to the group assignment of patients were provided one week training in the use of the scales and subsequently evaluated all patients at baseline, after the 4-week intervention, and at the end of the one-year follow-up. After training, the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) assessing the inter-rater reliability of the 4 clinicians for the total PANSS score(0.74) and the total PSP score (0.63) were satisfactory.Relapse during the 12-month period following hospital discharge was defined as follows:[13]a) the patient was re-hospitalized due to clinical deterioration,self-harm, or violent/destructive behavior; b) a total PANSS score increase of >25%; c) a CGI clinical change score of 6 or 7 (significant deterioration); or d) the patient met diagnostic criteria of active phase schizophrenia.

2.5 Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS 11.5. We conducted a modified intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis of outcome that included the 123 intervention group patients and 118 control group patients who completed the onemonth inpatient post-enrollment period (when the intervention was administered to the intervention group and the control group received routine inpatient care) without relapsing or dropping out. For patients who dropped out during the 1-year follow-up period,the last observed value carried forward (LOCF) method was employed. Statistical tests appropriate to the characteristics of the variable (i.e., dichotomous, ranked,or continuous) were conducted, including independent and matched t-tests, chi-square tests and rank tests.The main results between groups were assessed using repeated measures analysis of variance for unequaltime intervals between assessments. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

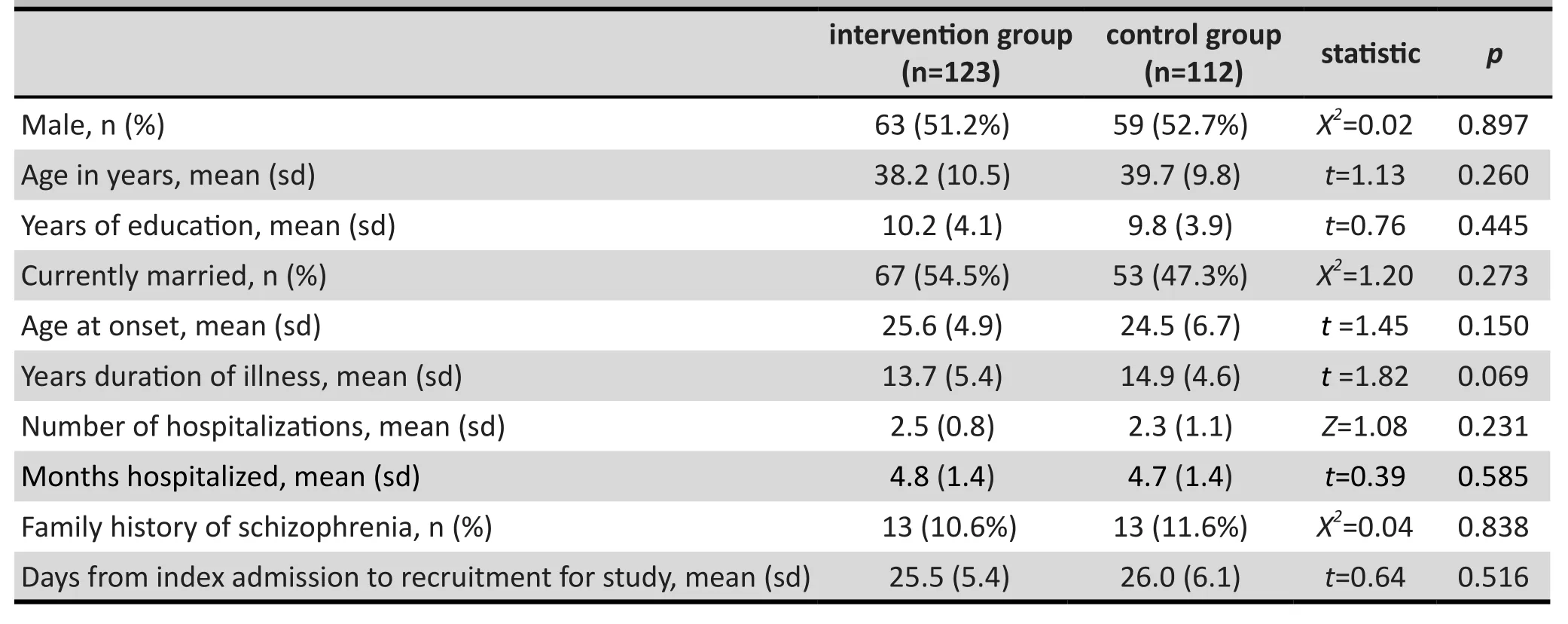

As shown in Table 1, there were no significant differences between the two groups in demographic characteristics, baseline illness characteristics, or family history of mental illness.

During the 12-month follow up, 13 (10.6%) of the 123 subjects in the intervention group experienced relapses (all were re-hospitalized once) and 23 (20.5%)of the 112 subjects in the control group experienced relapses (two of them were re-hospitalized twice; 21 were re-hospitalized once (X2=4.50,p=0.034).

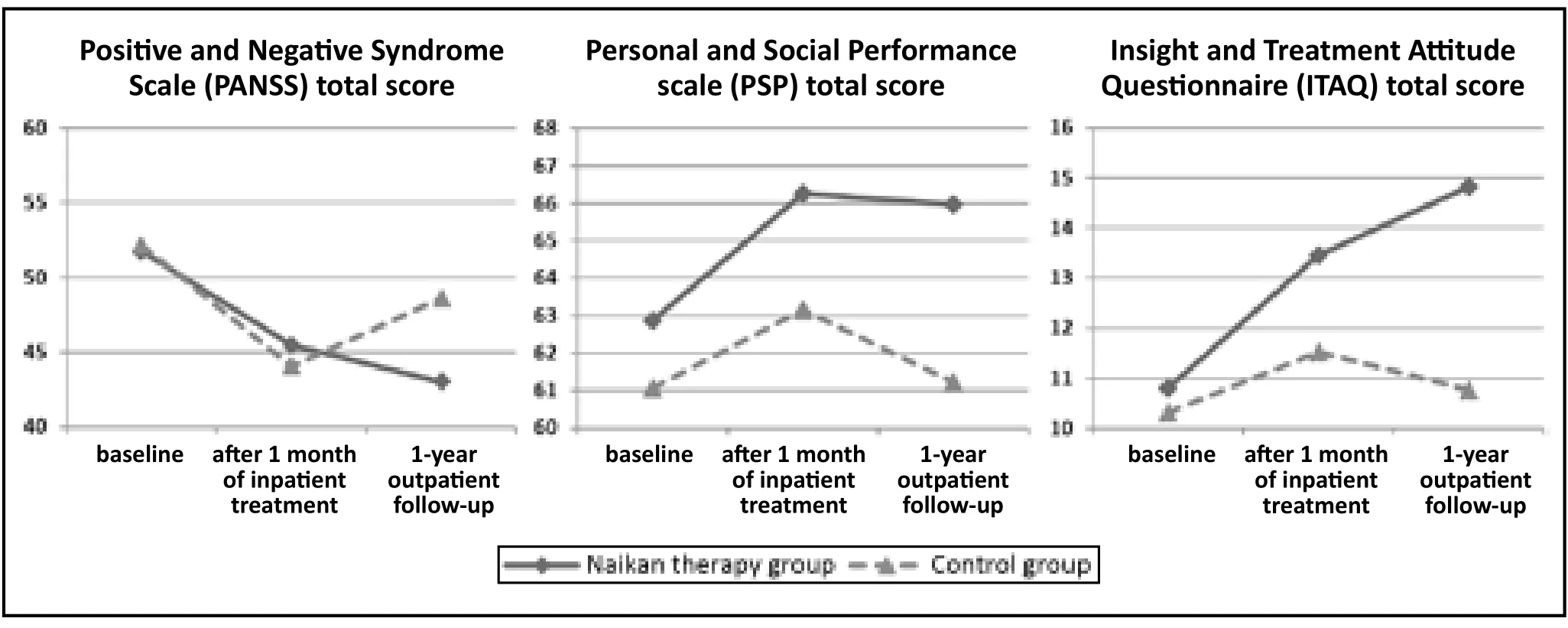

Changes in the PANSS total score and 5 subscales scores, PSP total score, and ITAP total score over the three time periods (baseline, after 1-month intervention,and after 1-year follow-up) are shown in Figure 2 and Table 2. The modified ITT repeated measures analysis of variance results found no significant differences in any of the 8 measures between the two groups at the time of enrollment. The PANSS, PSP, and ITAQ total scores all show significant main effects both for time and for group and significant time*group interaction effects. For all three measures the total scores improved during the 1-month inpatient treatment following recruitment, though the improvement in the PSP and ITAQ total scores was greater in the intervention group than in the control group (for PSP,t=2.72,p=0.007;for ITAQ,t=2.83,p=0.005). Over the 12-month followup, the improvement in total scores after the 1-month treatment was sustained or increased in the intervention group, but in the control group the scores of the three measures deteriorated. The significant time*groupinteraction effects for the three total scores show that the improvement over time in the intervention group was significantly greater than in the control group.

Table 1. Comparison of the baseline characteristics of patients with schizophrenia in the intervention and control groups

Figure 2. Results of PANSS, PSP, and ITAQ total scores in patients with shizophrenia after acute symptoms stabilized

Table 2. The result of repeated measures of analysis of variance of a modified intention-to-treat analysis of Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) scores, Personal and Social Performance scale (PSP)total score, and Insight and Treatment Aゆtude Questionnaire (ITAQ) total score of patients with schizophrenia in the intervention and control groups

Results for the 5 PANSS subscales are mixed. All 5 measures showed a significant main effect for time but only 2 measures (i.e., negative factor and anxiety/depression factor) show a significant main effect for group and only 3 measures (i.e., negative factor,excitatory factor, and anxiety/depression factor) have a significant time*group interaction effect. As was the case for the PANSS total score, all 5 subscale scores improved in both groups during the 1-month inpatient treatment period. Over the 1-year follow-up period there was a deterioration (compared to the result at the end of the 1-month treatment) in all 5 measures in the control group and in 2 of the 5 measures (the positive factor and cognitive factor) in the intervention group. The improvement in the other three measures –the positive, excitatory, and anxiety/depression PANSS factors – was significantly greater in the intervention group than in the control group.

The mean (sd) chlorpromazine-equivalent dosage of antipsychotic medications in the intervention and control groups at the time of recruitment were 217 (62)versus 214 (53) mg/d, respectively (t=0.40,p=0.691).After 1 month of treatment the dosages were 213 (48)versus 216 (57) mg/d, respectively (t=0.44,p=0.662).After the 12-month follow-up period the dosages were 198 (40) versus 208 (45) mg/d, respectively (t=1.80,p=0.073). Compared to baseline, the mean dosage had decreased significantly at the end of follow-up in the intervention group (pairedt=2.86,p=0.005) while the change in dosage in the control group was not statistically significant (t=0.91,p=0.362). Repeated measures analysis of variance found that the main effect for time was significant (F=15.36,p<0.001) but the main effect for group was not significant (F=4.33,p=0.058) and the time*group interaction effect was not significant (F=1.21,p=0.342). However, the effect sizes of the intervention at recruitment, at the end of 1 month of treatment, and the end of the 12-month follow-up were 0.0046, 0.056, and 0.28, respectively,which indicates a more pronounced downward trend in the medication dosage in the intervention group compared to that in the control group.

4. Discussion

4.1 Main findings

This relatively large, single blind, randomized controlled trial found that a 1-month inpatient intervention of daily Naikan therapy used as an adjunctive treatment for schizophrenia (after active symptoms have been effectively treated using antipsychotic medication)can reduce psychotic symptoms (particularly negative symptoms), improve social functioning, enhance insight and – most importantly – significantly reduce re-hospitalization over a one-year period. This result confirms the findings of earlier studies that used smaller samples and followed patients for shorter periods of time.[4-6]We also found that one year after completing the intervention the dosage of antipsychotic medication used by patients provided Naikan therapy was lower than that of patients receiving standard treatment;but this result was not as robust as that for the change in symptoms, so further research will be needed to confirm this difference.

Naikan therapy was developed as a psychological treatment in Japan by Yoshimoto Inobu in 1953 based on Oriental culture.[4]The basic tenet that individuals can control their own emotional responses and behaviors through self-directed cognitive exercises is consistent with the Chinese world view, so this therapy has become increasingly popular in clinical seゆngs in China.[14]However, the mechanism of action of Naikan therapy remains uncertain. The intense focus the therapy places on improving interpersonal relationships and on self-examination of one’s own role in problematic relationships or experiences may help patients decrease their self-centeredness, improve their insight about their illness, and enhance their engagement in the social world.[15]The reasons for relapse in schizophrenia are still being debated by specialists,[16]but there is general agreement that relapse is primarily caused by poor drug adherence, poor family relationships, residual psychotic symptoms, and lack of insight.[17,18]The reduced relapse rates seen when adjunctive Naikan therapy is provided to patients with schizophrenia who have recovered from an acute episode of illness is most probably related to the sustained remission of active psychotic symptoms,improved insight (and, thus, medication adherence),and better social functioning of patients receiving Naikan therapy compared to those receiving standard treatment.

4.2 Limitations

There are several issues that need to be considered when interpreting these results: a) Patients in this study were all inpatients at a single psychiatric hospital and they had all completed junior high school. It is uncertain whether or not Naikan therapy would be effective for a less selective group of individuals with schizophrenia or for those with lower levels of education. b) As employed in this study, Naikan therapy is an intensive daily intervention that continues for one month and is provided to inpatients after their acute symptoms have resolved using antipsychotic medication. It is unknown whether or not this therapy would be effective if administered on an outpatient basis or on a less intensive schedule. c) We used a modified ITT analysis that excluded 2 patients from the intervention group who relapsed during the 1-month intervention and 5 patients from the control group who relapsed (and 1 that had a hypertensive crisis) during the 1-month following recruitment. We excluded these individuals so the results would assess the long-term effects of persons who completed the Naikan intervention.Using a more standard ITT analysis that included these dropout patients would have made the overall results stronger than those we reported (because more patients relapsed during the first month of treatment in the control group than in the intervention group). d)The assessment of social function in the study using the PSP – including items about family function and work function – is not well-suited to assessing inpatients, so the use of this measure at baseline and at the end of the 1-month intervention (when the participants were hospitalized) may have been biased. 3) The assessment of medication adherence was primarily based on patient and family self-reports, so it may not have been accurate. e) The 12-month follow-up period is longer than that used in many studies, but it remains unclear how long the effect of Naikan therapy persists: does one treatment episode have a permanent beneficial effect or is there a need for regular booster sessions?

4.3 Implication

This study provides robust support for the beneficial effects of using adjunctive Naikan therapy in the rehabilitative treatment of Chinese patients who have recovered from an acute episode of schizophrenia.However, the sample was quite selective so further research will be needed to confirm the results in outpatients, in patients with lower levels of education,and in patients from different parts of China. Further work is also needed to assess the optional duration,intensity, and interval between booster sessions. Data from larger samples could be used to identify the demographic and clinical factors that predict favorable outcome from Naikan therapy and, thus, would help characterize the patients that should preferentially be provided with this treatment. Finally, standardized methods of training clinicians to provide Naikan therapy will be needed before this treatment can be widely employed in China or elsewhere.

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest related to this manuscript.

Funding

None.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the research review committee of Shanghai Mental Health Center of Xuhui district.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and their guardians before the study.

1. Mao PX, Tang YL, Chen Q, Wang Y, Luo Q, Xu Y, et al.[Awareness to the risk factors of relapse in schizophrenia].Zhongguo Xin Li Wei Sheng Za Zhi. 2004; 18(4): 264-268. Chinese. doi: http://dx.chinadoi.cn/10.3321/j.issn:1000-6729.2004.04.019

2. Ascher-Svanum H, Zhu B, Faries DE, Salkever D, Slade EP,Peng X, et al. The cost of relapse and the predictors of relapse in the treatment of schizophrenia.BMC Psychiatry.2010; 10: 2. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-10-2

3. Li C, He Y. Morita therapy for schizophrenia.Schizophr Bull.2008; 34(6): 1021-1023. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbn124

4. Ozawa-de Silva C. Demystifying Japanese therapy: an analysis of Naikan and the Ajase Complex through Buddhist thought.Ethos. 2007; 35(4): 411-444

5. Cheng J, Xu XT, Mao FQ, Liu X, Cao T, Du JY, et al. [Study of Naikan cognitive therapy to improve the social function during rehabilitation of schizophrenia].Tianjin Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2014; 20(4): 313-315. Chinese

6. Wang M, Chen J, Wang ZC. [A study of Naikan therapy in the treatment of social function rehabilitation for schizophrenia].Lin Chuang Jing Shen Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2010; 20(1): 58-59.Chinese

7. Mao RJ, Zhu G, Wang ZW, Huang YP, Jie Y, Shi BH, et al.[Effect of Naikan therapy and behavioral therapy on recent medication adherence in schizophrenic patients].Lin Chuang Jing Shen Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2014; 24(4): 214-219. Chinese

8. World Health Organization. Fan XD, Wang XD, Yu X. translated. [ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioral Disorders (Clinical Description and Diagnosis)].Beijing: People’s Health Publishing House; 1993. pp:72-80. Chinese. doi: http://dx.chinadoi.cn/10.1097/MCD.0b013e32832e38a6

9. Zhang MY. [Psychiatric Rating Scale Manual, 2nd edition].Changsha: Hunan Science and Technology Press; 1998. pp:150-153. Chinese

10. He YL, Zhang MY. [The Chinese norm and factor analysis of PANSS].Zhongguo Lin Chuang Xin Li Xue Za Zhi. 2000;8(2): 65-69. Chinese. doi: http://dx.chinadoi.cn/10.3969/j.issn.1005-3611.2000.02.001

11. Si TM, Shu L, Tian CH, Su YA, Yan J, Cheng J, et al. [Evaluation of reliability and validity of the Chinese version of personal and social performance scale in patients with schizophrenia].Zhongguo Xin Li Wei Sheng Za Zhi. 2009; 23(11): 790-793. Chinese. doi: http://dx.chinadoi.cn/10.3969/j.issn.1000-6729.2009.11.008

12. Liu HQ, Zhang PY, Shang L, Yang PD, Wu HW. [Schizophrenia insight: “Application of the insight and treatment attitude questionnaire”].Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 1995; 7: 158-161.Chinese

13. Csernansky JG, Mahmoud R, Brenner R. A comparison of risperidone and haloperidol for the prevention of relapse in patients with schizophrenia.N Engl J Med. 2002; 346: 16-22.doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa002028

14. Zhang YB, Chen J, Wang ZC. [Application and development of Naikan therapy].Lin Chuang Jing Shen Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2010;20(1): 61-63. Chinese

15. Li ZT. [NaiKan therapy].Jian Kang Xin Li Xue. 1996; 4: 10-11.Chinese

16. San L, Bernardo M, Gómez A, Peña M. Factors associated with relapse in patients with schizophrenia.Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2013; 17: 2-9. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/136 51501.2012.687452

17. Olivares J M, Sermon J, Hemels M, Schreiner A. Definitions and drivers of relapse in patients with schizophrenia: a systematic literature review.Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2013; 12(1):32. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1744-859X-12-32

18. Mi WF, Zou LY, Li ZM, Cheng J, Geng T, Du B, et al.[Compliance with antipsychotic treatment and relapse in schizophrenia].Zhong Hua Jing Shen Ke Za Zhi. 2012; 45:25-28. Chinese. doi: http://dx.chinadoi.cn/10.3760/cma.j.issn.1006-7884.2012.01.011

, 2015-05-11; accepted, 2015-08-23)

Zhang Hong, an associate chief physician, graduated from Tongji University Medical School in 1995.She has been working in the psychiatric department of the Shanghai Xuhui Mental Health Center since 2001 and is currently the head of the medical department and a ward director at the hospital.Her current research activities focus on the rehabilitation and treatment of mental disorders.

对内观疗法辅助治疗精神分裂症疗效的1年随访:一项单盲、随机对照研究

张红,李晨虎,赵立宇,占归来

内观疗法;精神分裂症;复发;社会功能;随机对照试验;中国

Background:Current treatments for schizophrenia are often only partially effective.Aim:Assess the possible benefit of using adjunctive Naikan therapy, a cognitive approach based on selfreflection that originated in Japan for the treatment of schizophrenia.Methods:After resolution of acute psychotic symptoms, 235 psychiatric inpatients with schizophrenia who had a middle school education or higher were randomly assigned to a control group (n=112) that

routine medication and inpatient rehabilitative treatment or an intervention group (n=123) that also received adjunctive Naikan therapy for 2 hours daily, 5 days a week for 4 weeks. The patients were then discharged and followed up for 12 months. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), Personal and Social Performance scale (PSP), and Insight and Aゆtude Questionnaire (ITAQ) were used to assess patients at enrollment, after the 1-month intervention, and after the 12-month follow-up. Evaluators were blind to the group assignment of patients.Results:Only 13 (10.6%) of the intervention group participants relapsed over the 12-month follow-up, but 23(20.5%) control group participants relapsed (X2=4.50,p=0.034). Using a modified intention-to-treat analysis and a repeated measure analysis of variance, the PANSS, PSP, and ITAQ total scores all showed significantly greater improvement over the 12-month follow-up in the Naikan group than in the control group. The drop in mean chlorpromazine-equivalent dosage from enrollment to the end of follow-up was significantly different in the intervention group but not in the control group, though the change in dosage over time between groups was not statistically significant.Conclusions:This study provides robust support for the effectiveness of Naikan therapy as an adjunctive treatment during the recovery period of schizophrenia. Compared to treatment as usually, adjunctive Naikan therapy can sustain the improvement in psychotic symptoms achieved during acute treatment, improve insight about the illness, enhance social functioning, and reduce relapse over a one-year follow-up period.Further research of this treatment with larger and more diverse samples of patients with schizophrenia is merited.

[Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2015, 27(4): 220-227.

http://dx.doi.org/10.11919/j.issn.1002-0829.215055]

Shanghai Xuhui District Mental Health Center, Shanghai, China

*correspondence: li_chenhu@163.com

A full-text Chinese translation of this article will be available at http://dx.doi.org/10.11919/j.issn.1002-0829.215055 on Oct 26, 2015.

背景:目前的精神分裂症治疗常常只是部分有效。目的:评估在精神分裂症的治疗中使用辅助性内观疗法可能带来的益处,该疗法是一种源于日本、基于内省的认知方法。方法:在急性精神病性症状缓解后,235例具有初中以上学历的精神分裂症住院患者被随机分为对照组 (n=112) 或干预组 (n=123)。前者接受常规药物治疗和住院康复治疗,后者在此基础上接受辅助性内观疗法,每天2 小时,每周5天,为期4周。对所有患者在出院后进行12个月的随访。在基线、干预1个月后以及随访12个月后,采用阳性和阴性症状量表 (Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, PANSS)、个人和社会功能量表 (Personal and Social Performance scale, PSP) 以及自知力与治疗态度问卷 (Insight and Attitude Questionnaire, ITAQ) 分别对患者进行评估。对评估者使用盲法,隐瞒患者的分组情况。结果:在12个月的随访中干预组只有13例 (10.6%)复发,但是对照组有23例 (20.5%) 复发 (X2=4.50,p=0.034)。使用修正的意向治疗分析和重复测量方差分析,内观疗法组的PANSS、PSP和ITAQ总分均在12个月的随访中比对照组有更显著的改善。尽管两组之间药物剂量(氯丙嗪等效剂量)随时间变化趋势的差异并无统计学意义,但从入组到随访终点,干预组的平均剂量显著减少而对照组的减少在统计学上并不显著。结论:本研究有力支持了内观疗法作为辅助治疗在精神分裂症康复期是有效的。相比于常规治疗,辅以内观疗法可以维持急性治疗期间所取得的精神病性症状改善的疗效、提高对疾病的自知力、提高社会功能,并在一年的随访期内减少复发。这值得我们在更大、更多样化的精神分裂症患者样本中进一步研究这种治疗方法。

本文全文中文版从2015年10月26日起在

http://dx.doi.org/10.11919/j.issn.1002-0829.215055可供免费阅览下载

- 上海精神医学的其它文章

- Introduction to longitudinal data analysis in psychiatric research

- Case report of comorbid schizophrenia and obsessivecompulsive disorder in a patient who was tube-fed for four years by family members because of his refusal to eat

- Obsessive compulsive symptoms in bipolar disorder patients:a comorbid disorder or a subtype of bipolar disorder?

- Comorbid bipolar disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder

- Comparison of the effectiveness of duloxetine in depressed patients with and without a family history of affective disorders in first-degree relatives

- Treatment of major depressive disorders with generic duloxetine and paroxetine: a multi-centered, double-blind,double-dummy, randomized controlled clinical trial