Zoned In 35 Years of China’s Special Economic Zones

by+Alex+Liu

“In the spring of 1979, an old man circled the land by the South China Sea…” The song “Spring Tale”vividly depicts how Deng Xiaoping, dubbed the chief architect of Chinas reform and opening-up, mapped out the plan to establish special economic zones (SEZs).

Thirty-five years ago, as China emerged from the shadow of the “cultural revolution” (1966-1976), policymakers decided to open the door to the global economy. On August 26, 1980, the 15th meeting of the Standing Committee of the 5th National Peoples Congress (NPC) passed a decision to set up four SEZs in Guangdong Provinces Shenzhen, Zhuhai and Shantou, and Fujian Provinces Xiamen, in which special policies would be adopted to explore the path of reform and opening-up. At that time, The New York Times commented that the “iron curtain” was raised, heralding the beginning of Chinas great reform.

Cross the River by Feeling the Stones

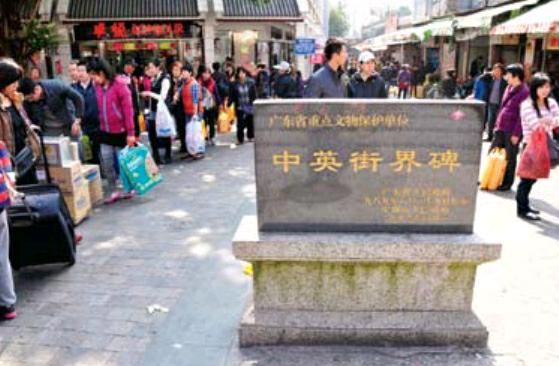

Why did China choose the southern province of Guangdong as the primary location to establish SEZs? According to Ding Li, director of the Research Center for Regional and Enterprise Competitiveness under Guangdong Academy of Social Sciences, after the end of the “cultural revolution,” the central government of China was eager to find solutions for economic development, while the policymakers of Guangdong formulated a plan to develop Baoan County (todays Shenzhen City) and Zhuhai County (todays Zhuhai City) adjacent to Hong Kong and Macao into manufacturing bases for exported products, which coincided with the aims of the central government.

According to the book Xi Zhongxun Governing Guangdong, in early July 1978, when Xi conducted his first inspection tour of Guangdong counties as the provinces Party chief, he visited Baoan County bordering the New Territories of Hong Kong. The sharp contrast across the border deeply impressed him. At that time, the daily per capita income of Baoan farmers was less than a yuan, only one sixtieth of the average earnings of their Hong Kong counterparts just across the river. Chinese policymakers felt the urgent need to enable mainland people to become wealthy and catch up with global development.

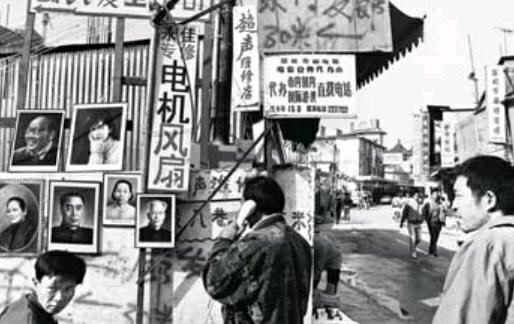

In the early days of the reform and opening-up process, China needed to “cross the river by feeling the stones.” The same held true for the establishment of SEZs. “The SEZs were designed to be‘windows of the country to attract overseas capital and technology,” explains Lin Guijun, vice president of the University of International Business and Economics. “In the SEZs, special policies were formulated to facilitate foreign investment including money from overseas Chinese and develop export-oriented manufacturing to increase the countrys foreign exchange revenue, with which China could purchase advanced technology and equipment from abroad and realize industrialization. Initially, the SEZs only served as hotbeds for investment from overseas Chinese people. In 1984, China began to introduce foreign direct investment.”

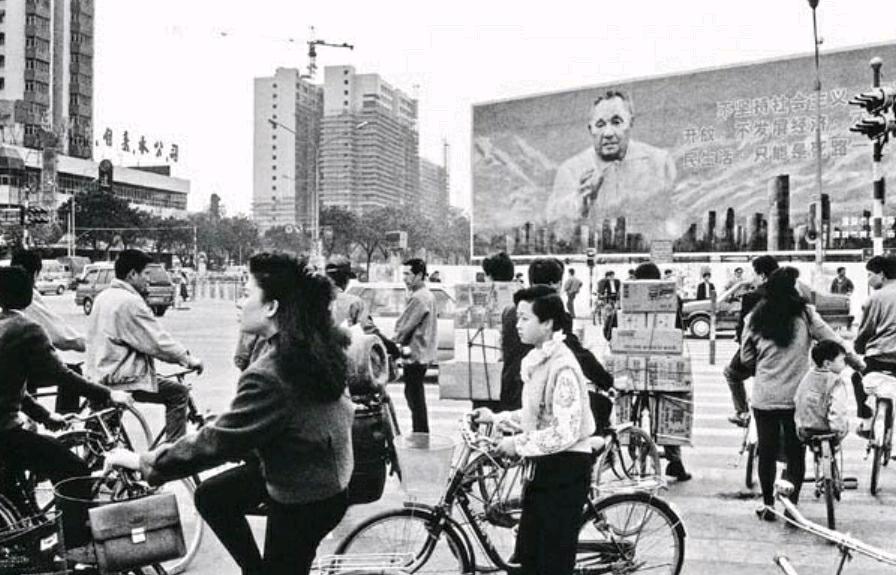

In the early 1980s, the 50-meter-long Luohu Bridge linking Shenzhen and Hong Kong was considered a bridge between the Chinese mainland and the outside world. When crossing the bridge, mainlanders were not only impressed by icons of modern lifestyles such as jeans, sunglasses, and boomboxes, but also sensed the technological revolution and economic globalization sweeping around the world. Meanwhile, for Hong Kong people who crossed the bridge to the mainland as well as later foreign investors, they witnessed the Chinese peoples determination in reform and opening-up and the tremendous changes that the policy brought to Chinas SEZs: Shenzhen issued the countrys first stock and launched the countrys first auction of land. Xiamen became the first to introduce foreign investment to build a local airport and establish a local airline as well as taking the lead in founding joint venture banks. Zhuhai was the first to allow technology appraised as capital stock and build cross-border industrial parks. Shantou took the lead in deploying officials via an engagement system instead of appointment.

In 1985, Deng Xiaoping stated that “Shenzhen is an experiment, so is the SEZ. In fact, our reform and opening-up policy is also an experiment. From a broader perspective, the whole world is an experiment.” After accumulating certain experience through the first group of SEZs, China accelerated its paces of constructing more SEZs. In April 1988, the Hainan SEZ was officially established, which is the countrys first and only provincial-level SEZ. In 2010, Kashgar and Horgos, both border towns in northwestern Chinas Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, were declared SEZs, increasing the tally of Chinas SEZs to seven.

SEZ Effect

In the beginning, SEZs served as the “test fields” or “windows” of Chinas reform and opening-up. Zhao Zhenhua, a professor of economics at the Party School of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (CPC), noted that the establishment of SEZs essentially cracked open Chinas door to the outside world after decades of seclusion, through which the country achieved internationalization in areas including capital, technology, and management.

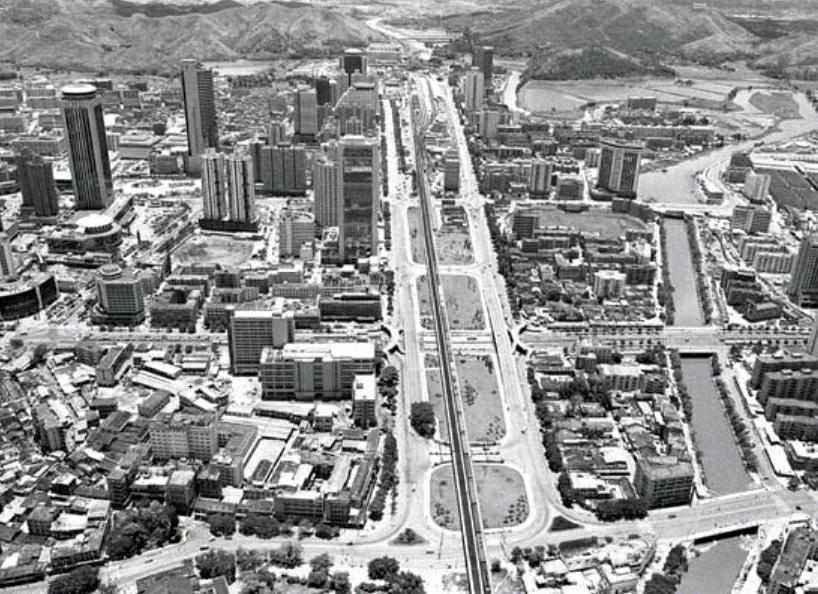

With the slogan “Time is money and efficiency is life,” SEZs saw rapid development, especially in the two decades from the 1990s to the early 21st Century. In the two decades-plus before the 2008 world financial crisis, Shenzhens GDP grew at an annual rate of 27.3 percent, and the city transformed from a fishing village into one of Chinas four largest cities. Compared to 1980, the gross industrial output value of Zhuhai multiplied 1,370 times by 2007. The same year, Hainans gross industrial output value hit 100 billion yuan, about 36 times its figure two decades ago.

More importantly, the example set by the SEZs radiated across the country and even the world. China further opened 14 coastal cities including Tianjin and Dalian, and then the three coastal open economic regions that cover the Yangtze River Delta, the Pearl River Delta, and Fujian Provinces Xiamen, Zhangzhou and Quanzhou. Later, comprehensive reform pilot areas such as Shanghai Pudong New Area and Tianjin Binhai New Area were founded. Recently, free trade zones in Shanghai, Guangdong, Tianjin and Fujian were consecutively launched, marking the emergence of an even more open China. After more than three decades of reform and openingup, Chinas global GDP rank has climbed from 10th to second. In 1980, Chinas imports and exports accounted for less than one percent of global trade. Now, China is the worlds biggest trader.

The great success of Chinas SEZs has inspired many developing countries to follow suit. On August 25, 2015, the Caracas-based El Universal published an article quoting Venezuelan Minister of Planning Ricardo José Menéndez Prieto as saying that Venezuela would dispatch personnel from sectors such as technology, industry and trade to China to learn from its experience building SEZs as well as in other fields.

Moving Forward

No one questions SEZs critical role in fueling Chinas reform and opening-up process; they are considered a major driver of the countrys economic miracle over the last three decades. However, as increasing numbers of open cities and new pilot areas emerged in China, some began to doubt whether the SEZs can maintain their“special” status. What will ultimately become of the SEZs?

According to Zhang Yansheng, secretary-general of the Academic Committee at National Development and Reform Commission, SEZs focused on developing export-oriented processing and compensation trade at first. However, the negative impact of such a development mode began to cause more pressure over time. For instance, some enterprises primarily profit off of export tax rebates instead of export trade, lacking the incentive to promote independent innovation and build their own brands. Furthermore, the development mode is resource-consuming and unsustainable, resulting in severe environmental deterioration.

Over the past three decades, Chinas reform and opening-up injected tremendous vitality in the development of the SEZs. As the countrys reform has entered the “deep water” zone, economic restructuring becomes the main driver for Chinas economic development.

In fact, administrators of SEZs like Shenzhen have realized that they must further reform their economic structure and pave the road for the shift from a factor-driven economy to an innovation-driven one. For example, Shenzhen was already developing hi-tech industries as early as the late 1990s, but its economic restructuring wasnt adequate until the 2008 world financial crisis.“The crisis threatened Shenzhens export-reliant economy,” recalls Xie Juemin, vice director of the Economy, Trade and Information Commission of Shenzhen. “But Shenzhen took the challenge as an opportunity to upgrade its economic structure.”

In this context, a number of Chinese and international companies swarmed Shenzhen, sewing a complete hi-tech industrial cluster and locally cultivating now-internationally-acclaimed hitech firms such as Tencent and BGI.

“Chinas first group of SEZs is turning 35,” remarks Ding Li. “They were once models for the rest of the country and even the world. In the future, they will continue to play a lead and exemplary role in Chinas economic development. Chinas reform remains far from complete, with potential dividends to be tapped. Future reform will continue to require ‘test fields like the SEZs to work effectively.”

China Pictorial2015年10期