热带水果上食源性致病菌研究进展

马晨++李建国

摘 要 芒果、木瓜、椰子、菠萝、香蕉和鳄梨等曾发生多起食源性疾病爆发事件。诺瓦克病毒(Norovirus)和沙门氏菌(Salmonella)是高发性食源性致病微生物。综述与热带水果相关的食源性致病微生物、致病菌在热带水果上的行为以及致病菌侵染植物的过程,提出未来研究方向。

关键词 热带水果 ;食源性致病菌 ;存活/生长 ;侵染过程

分类号 S432

Foodborne Pathogens of Tropical Fruits

MA Chen LI JIanguo

(Analysis and Testing Center / Hainan Provincial Key Laboratory of Quality and Safety for

Tropical Fruits and Vegetables, Ministry of Agriculture Laboratory of Quality & Safety Risk

Assessment for Tropical Products, CATAS, Haikou, Hainan 571101, China)

Abstract Outbreaks of foodborne disease associated with tropical fruits have occurred, mainly associated with mango, payaya, coconut, pineapple, banana and avocado. Norovirus and Salmonella are the leading viral and bacterial pathogens, respectively. The frequency of foodborne pathogens contamination for tropical fruits is probably high because of growth and production environment and innate characteristics of fruit. This review is to discuss the foodborne pathogens associated tropical fruit consumption, pathogen behavior on tropical fruits, internalization of foodborne pathogen into plant and future research needs.

Keywords tropical fruits ; foodborne pathogens ; survival and growth ; internalization

近年来,欧美国家不断爆发新鲜果蔬上食源性致病菌中毒事件[1-4],引起了国内外广泛关注。沙门氏菌等可附着在果蔬表面,并可进入组织内部存活和繁殖[5-6]。所以,新鲜果蔬的微生物质量安全问题已成为国际食品安全焦点。热带水果中曾发生过多起食源性致病菌爆发事件[7]。在中国,香蕉、芒果、菠萝、火龙果等是深受人们喜爱的热带水果。海南、福建、广东、广西和台湾等地是我国热带水果主要产地。泰国、马来西亚等是主要进口国。这些地区大多缺乏标准的食品安全生产和采后管理 标准,疾病爆发预警体系和致病菌检测能力欠缺,可能导致大量食源性疾病爆发事件未被报道[7]。另外,这些地区水热充沛,动物粪便和植物交叉污染严重,食源性致病菌的污染风险可能较高。

热带水果本身性质,如生长环境、pH、表面特性、抑菌成分和损伤敏感性等是影响致病菌存活和生长的重要因素[8]。表1列出了常见热带水果的基本性质。其中,pH是决定致病菌在水果上生长的关键因素。pH≤4.0为高酸性水果,pH≥4.0为低酸性水果[8]。如表1所示,热带水果具有不同程度的抑菌活性。水果的不可食外皮是防止细菌污染的强力屏障,但分切时易与刀具发生交叉污染[9]。致病菌在水果损伤部位或切割面上生长良好[10]。因而,易损伤或挤压的水果,也易受致病菌感染。

综上所述,热带水果的种植和加工环境以及水果自身特性决定了其受食源性微生物感染的几率较高。随着全球热带水果消费量的剧增,热带水果微生物质量安全问题应引起广泛重视。本文主要从食源性致病菌种类、存活和生长规律及侵染途径等方面总结热带水果上食源性致病菌的研究进展,为保障热带水果微生物质量安全提供参考。

1 与热带水果相关的食源性致病菌

表2列出了与热带水果有关的食源性致病菌中毒事件。其中,沙门氏菌和诺瓦克病毒是最常见的食源性微生物。受污染的热带水果主要包括鳄梨、香蕉、芒果、木瓜、菠萝和椰子等。水果制品感染率较高。以下主要介绍细菌性食源性致病菌特征。

1.1 致病性大肠杆菌

肠出血性大肠杆菌和产志贺毒素大肠杆菌,尤其是Escherichia coli O157:H7是果蔬安全关注的焦点。该菌生长pH为4.4~9.0,生长温度7~46℃[8]。可引起肠出血、溶血性尿毒综合征及神经紊乱等征状。E. coli O157:H7感染的果蔬包括绿叶蔬菜、苹果汁、苜蓿芽和哈密瓜等[15]。热带水果中该菌的污染事件不多。1994年,美国爆发了由菠萝引起的肠出血性E. coli O11:H43感染事件(表2)。

1.2 沙门氏菌属

沙门氏菌(Salmonella)列居微生物性食物中毒事件首位。该菌生长pH为3.8~9.5,生长温度5.2~46.2℃[8]。典型症状为腹泻和严重腹部绞痛。沙门氏菌爆发事件中,涉及的热带水果有芒果、木瓜、菠萝和椰子等。芒果引起的沙门氏菌感染事件有5起,木瓜和椰子各3起,涉及的沙门氏菌血清型多样(表2)。新加坡曾爆发水果沙门氏菌感染事件,并引起造船工人感染[16];抽检的水果样品中白兰瓜、木瓜、菠萝和西瓜均检出沙门氏菌。另外,新鲜椰子是沙门氏菌生长的良好基质[17]。Kovacs[18]第一次从干椰子中分离出沙门氏菌。南威尔士、英国和新加坡都曾爆发食用椰子制品而导致的较大范围沙门氏菌感染(表2)。endprint

1.3 葡萄球菌属

葡萄球菌是存在于人类皮肤中的常见细菌,只有产毒素种类(金黄色葡萄球菌Staphylococcus aureus)是食源性致病菌。由于发病后病期短和类感冒症状,该菌的漏报率高达38倍[7]。香蕉及其制品中曾爆发金黄色葡萄球菌感染事件(表2)。

1.4 单增李斯特菌

目前没有热带水果中单增李斯特菌(Listeria Monocytogenes)感染事件的报道。该菌生长pH为4.4~9.4,生长温度-0.4~45℃[8]。对孕妇危害极大,可引起死胎或流产。常存在于植物表面、植物产品和加工环境中[8]。该菌可在冰箱储藏温度下生长。冷藏储存的新鲜或鲜切热带水果应该关注该菌的污染风险。

1.5 志贺氏菌

志贺氏菌只能感染人类。严格管理工人的个人卫生和车间消毒可避免食物中志贺氏菌感染。志贺氏菌爆发事件中,涉及的热带水果有鳄梨和椰子(表2)。1991年,泰国一所学校发生了食用椰奶甜品引起的志贺氏菌感染事件,导致200多人生病[19]。另外,鳄梨酱中也发生过两起该菌感染事件,均由加工人员的个人卫生造成。

1.6 其他食源性致病菌

弯曲肠杆菌感染通常与消费家禽有关。熟食店中禽肉和果蔬的交叉感染可引起果蔬污染[7]。此菌生长pH为4.4~9.0,生长温度32~45℃[8]。1999和2002年,菠萝和鳄梨沙拉酱中发生过两例Campylobacter jejuni爆发事件(表2)。

诺瓦克病毒是最常见的食源性致病微生物。其感染症状为恶心、腹泻、腹痛等。鳄梨、新鲜香蕉和菠萝及其制品上都曾爆发该病毒感染事件(表2)。

另外,部分芽孢杆菌(Bacillus cereus、Clostridium botulinum和 Clostridium perfringens)也是潜在的食源性致病菌。目前没有发现热带水果上芽孢杆菌感染事件。但是,热带水果储存环境常为部分或完全厌氧,有利于产芽孢菌生长和存活。

2 食源性致病菌在热带水果上存活和生长规律

致病菌可在土壤、灌溉水、果蔬叶际或根际和鲜切果蔬上存活和生长[6]。关注较多的食源性致病菌是Salmonella、Escherichia coli O157:H7和Listeria monocytogenes,环境耐受性为E. coli O157:H7 2.1 芒果 新鲜芒果、芒果汁和鲜切芒果是常见的消费形式。其食源性致病菌爆发率最高。研究发现,采后热冷处理是导致芒果感染沙门氏菌的主要原因[20]。据报道,芒果肉中,6和-10℃时E. coli O157:H7可存活13 d[21]。芒果汁中,25℃时耐酸性和非耐酸性E. coli O157:H7可存活6 d,3 d后数量迅速减少[22];7℃存活8 d;10℃时Salmonella Heidelberg可存活18天,20和37℃时存活9 d[23]。鲜切芒果中,23℃时E. coli O157:H7和Salmonella可以生长;12℃时只有Salmonella 可以生长;4℃时E. coli O157:H7和Salmonella可存活28 d;-20℃存活至少180 d[24]。Penteado等[25]发现,25℃时S. enteritidis和L. monocytogenes生长延滞期分别为19 和7.2 h,增代时间分别为0.66和1.44 h;10℃,只有L. monocytogenes生长;4℃两种菌可存活8 d;-20℃,S. enteritidis可存活5个月;L. monocytogenes可存活8个月。另外,当刀具中携带大于104 CFU/mL的S. enteritidis或者大于105 CFU/ml的L. monocytogenes时,切分芒果时存在交叉污染[25]。 2.2 木瓜 新鲜木瓜、木瓜汁、鲜切木瓜、木瓜甜品等是常见的消费形式。研究发现,印度加尔各答街边摊贩销售的鲜切木瓜菌落总数较高,可检出大肠菌群和肠道致病菌。30份样品中,E. coli检出率48%,S. aureus检出率17%,Salmonella检出率3%,Vibrio cholerae检出率3%[26]。在鲜切木瓜中,4℃时E. coli O157:H7和Salmonella可存活28 d;-20℃时至少存活180 d;23和12℃时E. coli O157:H7 和 Salmonella可以生长[24]。室温培养6 h,在鲜切木瓜块和柠檬表面处理的木瓜块上,Salmonella Typhi数量分别增长1.4和0.8 log CFU/mL;Shigella sonnei、S. flexneri和S. dysenteriae约增长2.0 log CFU/mL[27-28]。木瓜汁中,4、20和37℃时E. coli O157:H7均可以生长;25℃培养72 h,数量达到8.5 log CFU/mL;37℃,培养16 h,该菌数量达到最大值9.0 log CFU/mL;4℃时该菌生长缓慢[29-30];37℃,Salmonella快速生长到9.0 log CFU/mL;4℃,24 h,该菌数量约增长1.0 CFU/mL,然后数量减少[30]。木瓜肉中,10℃储存7 d、20℃储存2 d、30℃储存1 d后,S. enteritidis数量分别增长1.8、6.0和7.0 log CFU/g;增代时间分别为16.61、1.74 和0.66 h;10℃时增殖速率降低,但不抑制其生长[31]。Campylobacter jejuni在木瓜中不生长,以稳定数量存活并可能引起食源性疾病[28]。

2.3 椰子

消费形式主要有新鲜椰子(椰子水)、生吃椰肉或者作为添加成分。椰子外壳坚硬,食用时必须用刀剖开,所以在加工过程中受细菌感染的概率较大。研究发现,从印度新德里和帕蒂亚啦抽取150份椰子片,产肠毒素S.aureus检出率为58%,Shigella dysenteraie(1-5型)和S. flexneri(type 2a)检出率为15%[32]。含新鲜椰子甜品的S. aureus检出率明显高于不含新鲜椰子的甜品[33]。鲜切椰肉中,L. monocytogenes可在以下多种条件下生长:储藏温度2、4、8、12℃,储藏环境(非气调或气调环境:65% N2,30% CO2和5% O2),接种剂量2.0 log CFU/g或5.7 log CFU/g[34]。新鲜椰子水中,L. monocytogenes 可以存活和生长:4℃或10℃时生长迟缓,可储存数天;35℃时生长延滞期明显缩短,菌数明显增加[35]。

2.4 菠萝

菠萝消费形式包括鲜切、榨汁或作为食品添加成分。研究发现,致病菌只能在菠萝或菠萝汁中存活,不能生长。在菠萝汁中,4、20~25℃储存3 d,E. coli O157:H7不生长,该菌数量约降低0.1~0.5 log CFU/mL[29];4℃,24 h,检测不到Salmonella;37℃,前24 h,Salmonella数量约增长2.0 log CFU/mL,后数量下降[30];10℃时Salmonella Heidelberg存活18 d,20℃存活12 d,37℃存活9 d[23]。冷冻菠萝汁(-23℃)中各种致病菌可长时间存活:E. coli O157:H7和Salmonella可存活至少180 d;前6 h,Salmonella和E. coli O157:H7数量急速下降,然后Salmonella稳定在较低数量[36]。冷冻菠萝果肉中,6或-10℃时E. coli O157:H7可存活13 d[21]。

2.5 香蕉

香蕉常带皮完整销售,所以鲜切香蕉中致病菌的研究很少。Behrsing发现,18℃,接种到香蕉皮上的Listeria innocua, Salmonella和E. Coli可存活13 d[37]。-23℃,接种到香蕉果泥中的E. coli O157:H7、L. monocytogenes和 Salmonella可存活12周,低接种量的E. coli O157:H7仍可存活[36]。4℃,7 d内,接种到香蕉乳酪中的L. monocytogenes数量从4.0 log CFU/mL降低到3.5 logCFU/mL[38]。

2.6 番石榴

番石榴消费形式主要为鲜食、鲜切或榨汁。番石榴中曾分离出Staphylococcus aureus[7]。在番石榴果肉中,6℃或-10℃,E. coli O157:H7(接种量2 log CFU/mL)可存活13 d[21]。Tang等报道,Salmonella Typhi可在番石榴表面形成生物膜,接触时间越长其附着量越大[39]。在番石榴汁中,10℃时Salmonella Heidelberg可存活18 d,20℃存活12 d,37℃存活9 d[23]。

2.7 火龙果

火龙果pH在4.7~5.1,含糖量高,是致病菌生长的良好基质。Pui(2010)[40]报道,鲜切火龙果中沙门氏菌检出率较高:Salmonella spp.75%,S. Typhi 40% 和S. Typhimurium 25%。Sim等发现[41],28℃,8 h后,在低接种剂量下(2.5 log CFU/g) Salmonella大量增殖,数量约增长2.4~3.0 log CFU/g;高接种剂量(5.5 log CFU/g)下,数量约增长0.4~0.7 log CFU/g;12℃储存96 h后,在低接种剂量下,耐酸性和非耐酸性沙门氏菌数量均增长0.7~0.9 log CFU/g;4℃,Salmonella没有明显生长。环境耐受型沙门氏菌与非耐受菌株在鲜切火龙果上的存活和生长规律没有明显差异。

2.8 百香果

百香果常被作为果汁饮用。其外皮光滑并有蜡质层,不利于致病菌躲藏或附着。据报道,-20℃,S. enteritidis在冷冻百香果饮料中可存活90 d。常温下,初始接种剂量4.0~5.0 log CFU/mL时,百香果饮料对E. coli,Salmonella和Shigella有致死作用[42]。耐酸性和非耐酸性E. coli O157:H7在冷冻百香果果肉中数量稳定下降,12~21天后无法检出该菌。Behrsing等[37]在百香果外皮上接种L. innocua,Salmonella和 E. coli(约5.0~6.0 log CFU/ml),10℃储存6 d,可直接检测到L. Innocua,通过富集培养其他两种菌可以复活。

2.9 鳄梨

鳄梨常作为果酱或鲜果使用。鳄梨果酱中曾发生多起致病菌感染事件(表2),致病菌在鳄梨上存活规律的研究也较多。墨西哥街头摊贩和饭店销售的鳄梨酱中各种致病菌检出率为S.aureus 4.3%~10.3%,E. coli 54.3%~69%,Salmonella 0%~3.4%,L. monocytogenes 15.2%~17.2%[43]。S. aureus,E. coli,Salmonella和 L. monocytogenes均可在鳄梨皮和鳄梨汁中生长[29,30,43]。但是在中国,鳄梨的消费量较低。所以,相关研究不在此赘述,具体参考文献[7]。

3 食源性致病菌“侵染”热带水果过程

致病菌广泛存在于自然界,受污染的灌溉水、肥料、土壤、动物粪便、种子和昆虫等都是潜在污染源[44]。研究已证实,致病菌不仅附着在水果表面,还可通过多种方式进入水果组织内部并增殖[1,6]。关于致病菌侵染热带水果过程的研究非常少。据报道,Salmonella可以通过清洗水进入芒果或芒果果肉中,并在其中存活[20,45]。endprint

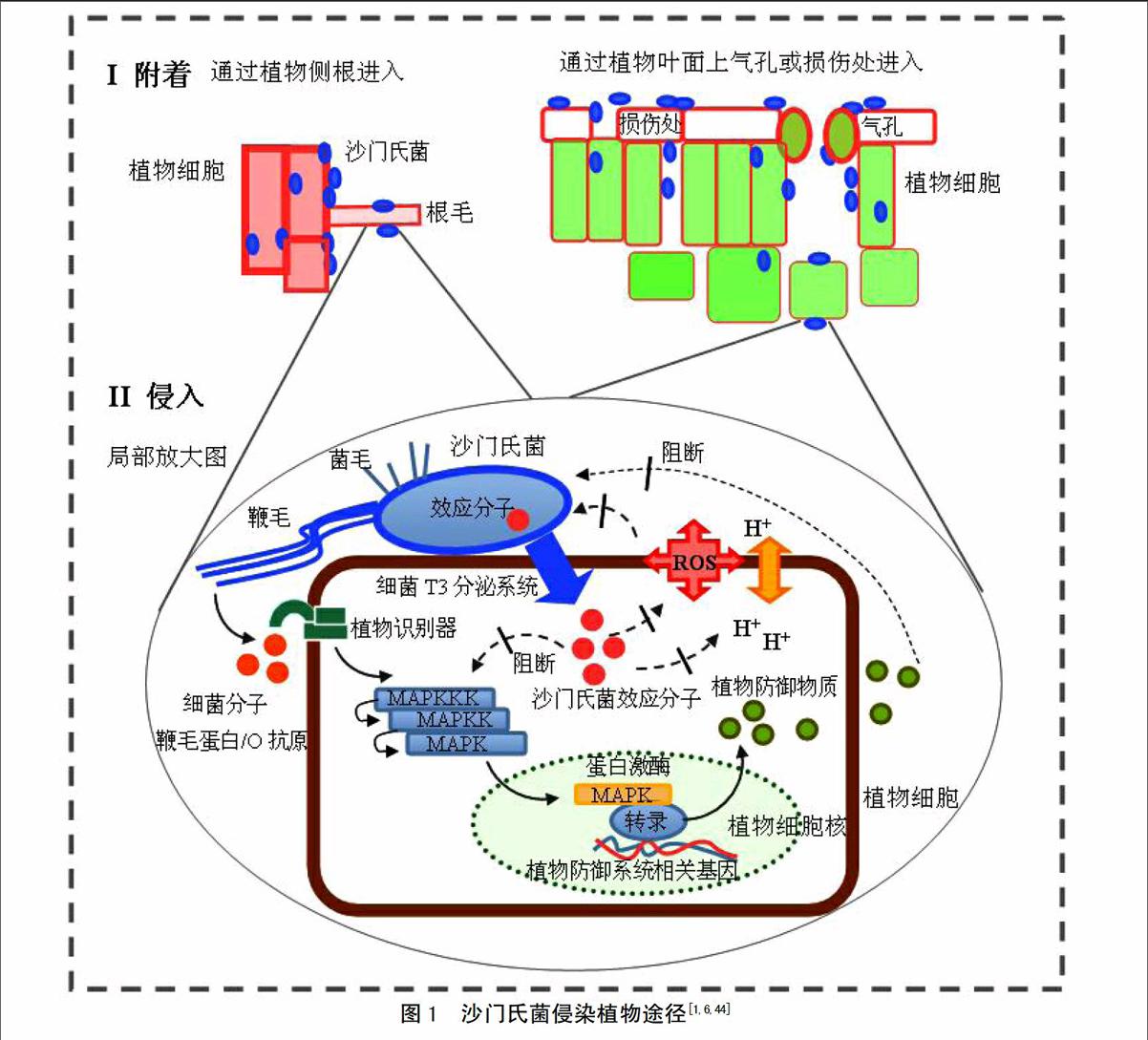

有研究表明,食源性致病菌侵入植物和动物细胞的机制可能相似[1,6]。致病菌“感染”植物细胞的过程分为以下几部分(图1)[46]。

3.1 致病菌附着在植物细胞表面

菌毛(fimbriae)是致病菌的主要附着结构。在苜蓿芽和芹菜附着过程中,证实了致病菌菌毛的重要作用[47]。Curli菌毛和基质主要成分纤维素参与沙门氏菌生物膜形成,并有利于其在苜蓿芽、芹菜、西红柿小叶上附着和存活[5,46,48-49]。菌株生物膜形成能力越强,其附着能力越强[49]。细菌粘附素MisL和鞭毛结构参与沙门氏菌附着生菜叶的过程[46,49-50]。细菌T3分泌系统和细胞间的群体效应(quorum sensing)在致病菌附着植物的过程中也发挥重要作用[46]。另外,Salmonella和E. coli O157:H7中参与附着的部分关键基因已确定[6,51]。

3.2 致病菌进入植物内部

致病菌常通过植物表面的天然“开放体”(如气孔和侧根等)、物理损伤部位或者通过渗透作用从灌溉水、种子浸泡水和清洗水进入植物内部[1,6]。研究发现,沙门氏菌可进入各种植物组织内部甚至可进入果实种子内部,并可在活体植株体中移动[47]。室内实验观察到S.Typhimurium存在于拟南芥根被皮细胞内部,低剂量沙门氏菌可以进入烟草原生质体[52-53]。但是,食源性致病菌是否可以进入植物细胞内部仍存在争议[46]。

致病菌主要通过T3分泌系统将效应蛋白注入动物细胞中,调控宿主细胞生理状态和免疫系统,以进入细胞内部。缺失T3分泌系统将降低致病菌在拟南芥中的繁殖能力[54]。但是,Iniguez等发现[55],缺失T3分泌系统有利于沙门氏菌进入苜蓿芽和小麦种子。所以,T3分泌系统可能参与致病菌进入植物细胞过程,但是具有植物特异性。Schikora 等发现[53],含O抗原的沙门氏菌感染拟南芥后,植物产生快速抵抗反应,并激活控制防御基因表达的蛋白酶,植物外观产生明显的萎蔫和枯黄症状。不含O抗原菌株感染后,植物未表现出明显症状。另外,沙门氏菌还可引起苜蓿属植物Medicago spp.免疫反应,去除细菌信号分子后植物内沙门氏菌数量增多[54]。所以,拟南芥和苜蓿属植物中可能存在识别沙门氏菌细菌因子(如O抗原)的专一性受体,并可激发植物免疫反应[55-56]。因此,食源性致病菌可能通过T3分泌系统进入植物细胞,但具体机制仍不清楚。

3.3 致病菌在植物内部增殖

在植物内部,致病菌必须消化植物内的营养物质供自身生长和繁殖。在沙门氏菌中发现了多糖降解酶的编码基因[55]。所以,在植物非原生质体空间,细菌可能直接降解植物细胞壁中的多糖合成自身物质。致病菌可能借助于其他植物病原菌或真菌的降解作用,间接利其降解产物[55]。研究发现,在Pseudomonas syringae和Xanthomonas campestris降解作用下,纤维糖和蔗糖含量提高,从而促进沙门氏菌和致病性大肠杆菌在植物内的存活或生长[46]。另外,某些植物病原菌分泌效应蛋白进入植物细胞,活化编码糖转运蛋白基因,使植物细胞分泌小分子糖进入质外体,供植物病原菌利用。沙门氏菌和大肠杆菌也可能利用这种方式,但机制仍不清楚[55]。

4 展望

目前,热带水果上食源性致病菌的研究还不深入。未来的研究重点应着眼于以下几方面:(1) 开发快速而有效的检测方法,建立有效致病菌溯源系统。果蔬中的致病菌含量通常较低,并可能诱导进入活的非可培养状态(viable but non-culture, VBNC)[51]。当应对食源性致病菌污染突发事件时,高灵敏度、快速的检测方法和及时溯源技术十分重要。(2)建立致病菌风险评估系统。按照危害因子识别、危害特征描述和风险管理等要求,确定高污染风险的热带水果种类和高发病率致病菌和可能引起致病菌污染的环节。采后处理是热带水果感染致病菌的主要环节。了解水果采后污染几率以及在采后处理、运输、储藏和销售时的交叉污染率,对于风险防控十分关键。(3)致病菌在热带水果上的行为。目前致病菌在热带水果上存活和生长规律的研究还较少。致病菌附着方式和内化机制,以及影响致病菌与植物间相互作用的环境因素还不清楚。开展这方面研究将有助于找出降低水果致病菌附着的有效方法,以及选育抗致病菌污染的植物品系。(4)不断开发有效致病菌防控措施。研究表明,传统的消毒方式,如氯表面清洗,无法达到减少食源性致病菌的目的。水果表面的土著微生物对消毒处理更加敏感,消毒处理后有利于致病菌在低竞争环境下存活和生长。所以,不断开发有效的水果表面消毒手段是防控致病菌污染的关键。

参考文献

[1] Schikora A, Garcia A V, Hirt H. Plants as alternative hosts for Salmonella[J]. Trends in Plant Science, 2012, 17(5): 245-249

[2] Abadias M, Usall J, Anguera M. et al. Microbiological quality of fresh, minimally-processed fruit and vegetables, and sprouts from retail establishments[J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2008, 31(123): 121-129.

[3] Bülent E. Survival characteristics of Salmonella Typhimurium and Escherichia coli O157:H7 in minimally processed lettuce during storage at different temperatures[J]. Journal fur Verbraucherschutz Lebensmittelsicherheit, 2011, 6(3): 339-342.endprint

[4] 刘程惠,胡文忠,何熠波,等. 鲜切果蔬病原微生物侵染及其生物控制的研究进展[J]. 食品工业科技,2012,33(18):362-366.

[5] Barak J D, Kramer L C, Hao L Y. Colonization of tomato plants by Salmonella enterica is cultivar dependent, and type 1 trichomes are preferred colonization sites[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2011, 77(2): 498-504.

[6] Brandl M T, Cox C E, Teplitski M. Salmonella interactions with plants and their associated microbiota[J]. Phytopathology, 2013, 103(4): 316-325.

[7] Strawn L K , Schneider K R, Danyluk MD. Microbial safety of tropical fruits[J]. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 2011, 51(2):132-145.

[8] Bassett J, McClure P. A risk assessment approach for fresh fruits[J]. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 2008, 104(4): 925-943.

[9] Beuchat L R. Ecological factors influencing survival and growth of human pathogens on raw fruits and vegetables[J]. Microbes and Infection, 2002, 4(4): 413-423.

[10] Dingman D W. Growth of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in bruised apple (Malus domestica) tissue as influenced by cultivar, date of harvest, and source[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2000, 66(3): 1 077-1 083.

[11] Mohamed S, Hassan Z, Abd Hamid N. Antimicrobial activity of some tropical fruit wastes (guava, starfruit, banana, papaya, passionfruit, langsat, duku, rambutan and rambai)[J]. Pertanika Journal of Tropical Agricultural Science, 1994, 17(3): 219-227.

[12] Mandal S M, Dey S, Mandal M, et al. Identification and structural insights of three novel antimicrobial peptides isolated from green coconut water[J]. Peptides, 2009, 30(4): 633-637.

[13] Engels C, Schieber A, Gānzle MG. Inhibitory spectrum and mode of antimicrobial action of gallotannins from mango kernels (Mangifera indica L.)[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2011, 77(7): 2 215-2 223.

[14] Moneruzzaman K M, Md J S, Mat N, et al. Bioactive constituents, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of three cultivars of wax apple (Syzygium samarangense L.) fruits[J]. Research Journal of Biotechnology, 2015, 10(1): 7-16.

[15] Sivapalasingam S, Friedman C R, Cohen L, et al. Fresh produce: a growing cause of outbreaks of foodborne illness in the United States, 1973 through 1997[J]. Journal of Food Protection, 2004, 67(10): 2 342-2 353.

[16] Ooi P L. A shipyard outbreak of Salmonellosis traced to contaminated fruits and vegetables[J]. Annals of the Academy of Medicine Singapore, 1997, 26(5): 539-543.endprint

[17] Schaffner C P, Mosbach K, Bibit V C, et al. Coconut and Salmonella infections[J]. Appl Microbiol, 1967, 15(3): 471-475.

[18] Kovacs N. Salmonellae in desiccated coconut, egg pulp, fertilizer, meat-meal, and mesenteric glands: Preliminary reports[J]. The Medical Journal of Australia, 1959, 46(17): 557-559.

[19] Hoge C W, Bodhidatta L, Tungtaem C, et al. Emergence of nalidixic acid resistant Shigella dysenteriae type 1 in Thailand: An outbreak associated with consumption of coconut milk dessert[J]. International Journal of Epidemioloy, 1995, 24(6): 1 228-1 232.

[20] Penteado A L. Evidence of Salmonella internalization into fresh mangos during simulated postharvest insect disinfestations procedures[J]. Journal of Food Protection, 2004, 67(1): 181-184.

[21] Leite C C, Guimaraes A G, da Silva M D, et al. Evaluation of the behavior of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in fruit pulp[J]. Higiene Alimentar, 2002, 16: 67-73.

[22] Hsin-Yi C, Chou C. Acid adaptation and temperature effect on the survival of E. coli O157:H7 in acidic fruit juice and lactic fermented milk product[J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2001, 70(1-2):189-195.

[23] EI-Safey M E. Behavior of Salmonella heideberg in fruit juices[J]. International Journal of Nutrition and Food Sciences, 2013, 2(2): 38-44.

[24] Strawn L K, Danyluk M D. Fate of Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Salmonella spp. on fresh and frozen cut mangoes and papayas[J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2010, 138 (1-2): 78-84

[25] Penteado A L, Castro M F P M D, Rezende A C B. Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis and Listeria monocytogenes in mango (Mangifera indica Linn) pulp: growth, survival and cross contamination[J]. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 2014, 94(13): 2 746-2 751.

[26] Guha A K, Mitra A, Mukhopadhyay R, et al. An evaluation of street-vended sliced papaya (Carica papaya) for bacteria and indicator micro-organisms of public health significance[J]. Food Microbiology, 2002, 19(6): 663-667.

[27] Escartin E F, Ayala A C, Lozano J S. Survival and growth of Salmonella and Shigella on sliced fresh fruit[J]. Journal of Food Protection, 1989, 52:471-472.

[28] Castillo A, Escartin E F. Survival of Campylobacter jejuni on sliced watermelon and papaya[J]. Journal of Food Protection, 1994, 57(2):166-168.

[29] Mutaku I, Erku W, Ashenafi M. Growth and survival of Escherichia coli O157:H7 in fresh tropical fruit juices at ambient and cold temperatures[J]. International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition, 2005, 56(2):133-139.endprint

[30] Yigeremu B, Bogale M, Ashenafi M. Fate of Salmonella species and E. coli in fresh-prepared orange, avocado, papaya, and pine apple juices[J]. Ethiopian Journal of Health Science, 2001, 11(2): 89-95.

[31] Penteado A L, Leitao M F F. Growth of Salmonella enteritidis in melon, watermelon and papaya pulp stored at different times and temperatures[J]. Food Control, 2004, 15(5): 369-373.

[32] Ghosh M, Wahi S, Kumar M et al. Prevalence of enterotoxigenic Staphylococcus aureus and Shigella spp. in some raw street vended Indian foods[J]. International Journal of Environmental Health Research, 2007, 17(2):151-156.

[33] Suklampoo L, Satta P, Senaard S. Study on contamination of Staphylococcus aureus in Thai dessert[C]. Proceedings of 41st Kasetsart University Annual Conference, 2003. Agro-Ind.: 85-91.

[34] Sinigaglia M, Bevilacqua A, Campaniello D, et al. Growth of Listeria monocytogenes in fresh-cut coconut as affected by storage conditions and inoculum size[J]. Journal of Food Protection, 2006, 69(4):820-825.

[35] Walter E H M, Kabuki D Y, Esper L M R, et al. Modelling the growth of Listeria monocytogenes in fresh green coconut (Cocos nucifera L.) water[J]. Food Microbiology, 2009, 26(6): 653-657.

[36] Oyarzabal O A, Nogueira M C L, Gombas D E. Survival of Escherichia coli O157:H7, Listeria monocytogenes, and Salmonella in juice concentrates[J]. Journal of Food Protection, 2003, 66(9): 1 595-1 598.

[37] Behrsing J, Jaeger J, Horlock F, et al. Survival of Listeria innocua, Salmonella Salford and Escherchia coli on the surface of fruit with inedible skins[J]. Postharvest Biology ans Technology, 2003, 29(3): 249-256.

[38] Sabreen M S, Korashy E. Incidence and survival of Listeria monocytogenes in yoghurt in Assiut City[J]. Assiut Veterinary Medical Journal, 2001, 45:122-133

[39] Tang P L, Pui C F,Wong W C, et al, Biofilm forming ability and time course study of growth of Salmonella Typii on fresh produce surfaces[J]. Internatinal Food Reseaech Journal, 2012,19(1):71-76.

[40] Pui C F, Wong W C, Chai L C, et al. Simultaneous detection of Salmonella spp., Salmonella Typhi and Salmonella Typhimurium in sliced fruits using multiplex PCR[J]. Food Control, 2010, 22(2): 337-342.

[41] Sim H L, Hong Y K, Yoon W B, et al. Behavior of Salmonella spp. and natural microbiota on fresh-cut dragon fruits at different storage temperatures[J]. International Journal of food microbiology, 2013, 160(3): 239-244.endprint

[42] Aea R T F, Bushnell O A. Survival times of selected enteropathogenic bacteria in frozen passionfruit nectar base[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 1962, 10(3): 277-279.

[43] Arvizu-Medrano S M, Iturriaga M H, Escartin E F. Indicator and pathogenic bacteria in guacamole and their behavior in avocado pulp[J]. Journal of Food Safety, 2001, 21(4):233-244.

[44] Critzer F J, Doyle M P. Microbial ecology of foodborne pathogens associated with produce[J]. Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 2010, 21(2): 125-130.

[45] Soto M, Chavez G, Baez M, et al. Internalization of Salmonella typhimurium into mango pulp and prevention of fruit pulp contamination by chlorine and copper ions[J]. International Journal of Environmental Health Research, 2007, 17(6): 453-459.

[46] Wiedemann A, Virlogeux-Payant I, Chaussé A M, et al. Interactions of Salmonella with animals and plants[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2015, 5: 791.

[47] Gu G, Hu J, Cevallos-Cevallos J M, et al. Internal colonization of Samonella enterica serovar Typhimurium in tomato plants[J]. Plos One, 2011, 6(11): e27340.

[48] Lapidotand A, Yarson S. Transfer of Samonella enterica servor typhimurium from contaminated irrigation water to parsley is dependent on curli and cellulose, the biofilm matrix components[J]. Journal of Food Protection, 2009, 72(3): 618-623.

[49] Kroupitski Y, Brandl M T, Pinto R, et al. Identification of Salmonella enterica genes with a role in persistence on lettuce leaves during cold storage by recombinase-based in vitro expression technology[J]. Phytopathology, 2013, 103(4), 362-372.

[50] Kroupitski Y, Golberg D, Belausov E, et al. Internalization of Salmonella enterica in leaves is induced by light and involves chemotaxis and penetration through open stomata[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2009, 75(19): 6 076-6 086.

[51] Yaron S, Romling U. Biofilm formation by enteric pathogens and its role in plant colonization and persistence[J]. Microbial Biotechnology, 2014, 7(6): 496-516.

[52] Samelis J, Ikeda J S, Sofos J N, Evaluation of the pH-dependent, stationary-phase acid tolerance in Listeria monocytogenes and Salmonella Typuimurium DT104 induced by culturing in media with 1% glucose: a comparative study with Escherichia coli O157:H7[J]. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 2003, 95(3): 563-575.

[53] Schikora A, Carreri A, Charpentier E, et al. The dark side of the salad: Samonella typhimurium overcomes the innate immmune response of Arabidopsis thaliana and shows an endopathogenic lifestyle[J]. Plos One, 2008, 3(5): e2279.

[54] Schikora A, Virlogeux-Payant I, Bueso E, et al. Conservation of Salmonella infection mechanisms in plants and animals[J]. PLoS One, 2011, 6(9): e24112

[55] Iniguez A L, Dong Y, Carter H D, et al. Regulation of enteric endophytic bacterial colonization by plant defenses[J]. Molecular Plant-microbe Interactions, 2005, 18(2):169-178.

[56] Deering A J, Mauer L J, Pruitt R E. Internalization of E. coli O157: H7 and Salmonella spp. in plants: a review[J]. Food Research International, 2012, 45(2): 567-575.endprint