Philippines, China and AIIB: Opportunities amidst Challenges

By Lucio Blanco Pitlo III

(The writer is a member of the Philippine Association for China Studies.)

Philippines, China and AIIB: Opportunities amidst Challenges

By Lucio Blanco Pitlo III

(The writer is a member of the Philippine Association for China Studies.)

T his year, the Philippines is estimated to become the world’s second fastest growing emerging economy after China at 6.3% GDP growth (China’s projected GDP growth is 7%). Among the key drivers behind this impressive performance includes the booming business process outsourcing sector, robust consumer spending, government spending such as in the area of postdisaster reconstruction (for Typhoon Haiyan-affected areas), and the ever-increasing overseas Filipino remittances. Since 2009, the country’s GDP has been steadily growing and this strong showing is remarkable considering that the country still lags behind in terms of attracting foreign direct investments as a result of institutional and infrastructure constraints.

Hence, the country’s potentials can definitely increase if foreign investment climate can be bolstered and one way of doing this is by improving infrastructure. This is where the value of AIIB can come in as an additional source of funding to finance local infrastructure projects. The Philippine government’s decision to sign up as a founding member of this Chinainitiated regional lending institution last October 2014 was therefore motivated by a strong economic impetus. In addition, Manila apparently looks at AIIB more as an economic vehicle rather than a geopolitical instrument to advance the interests of its leader-initiator, China. Participating in AIIB is a principled cooperation, which does not erode the country’s position in relation to certain political issues.

Based on the 2014-2015 Global Competitiveness Report published by the World Economic Forum, the Philippines was ranked poorly in relation to infrastructure – 91st out of 144 economies surveyed. In contrast, its neighboring ASEAN states have performed better – Malaysia (25th), Thailand (48th), Indonesia (56th ) and Vietnam (81st) – and this can partly explain why these states were able to corner more foreign capital. According to the report, infrastructure, along with institutions, macroeconomic environment and health and primary education, form the basic requirements of a competitive economy. The survey on infrastructure looked at quality, extensiveness and efficiency and it covered not only transportation, but also power and telecommunications. The report actually cited inadequate supply of infrastructure as the second problematic factor for doing business in the Philippines. This draws attention to the need for the state toallocate greater funds for infrastructure projects or for creating a policy climate conducive for attracting local and foreign investments alike in the infrastructure building sector. Revisiting Constitutional and statutory restrictions to foreign investments in this sector (and for all other sectors as well for that matter) is also essential.

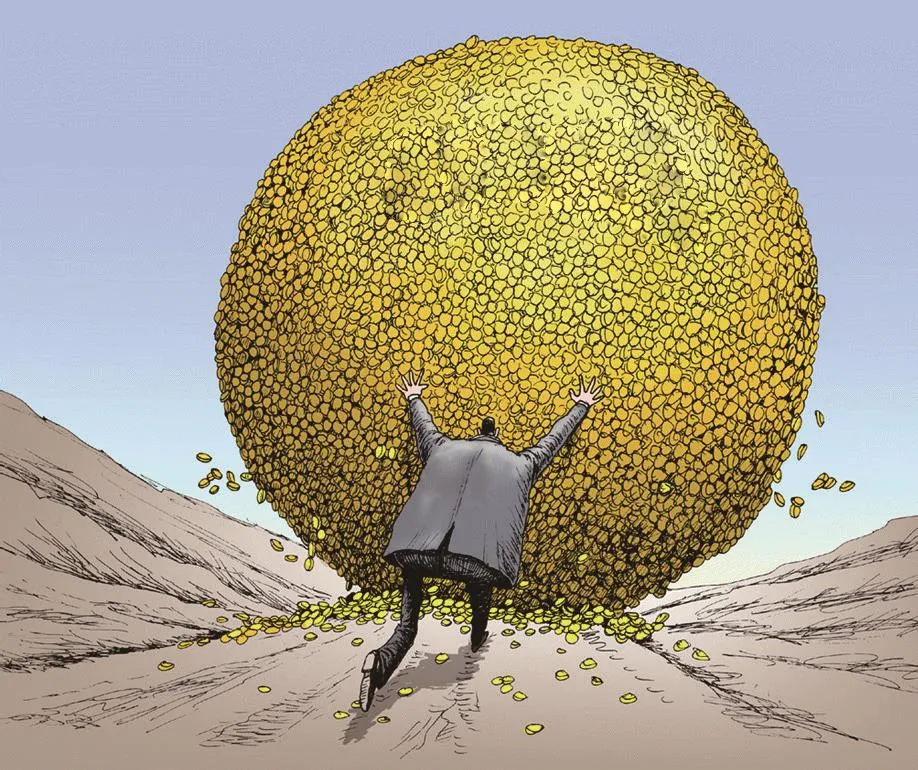

While other states were pressured to delay their application or adopted a “wait-and-see” approach on who else will join before they expressed their interest, the Philippines resolutely took action and became one of the early signatories to the document that established AIIB. That it did so despite the disputes in the South China Sea (SCS) signify that the Philippine government shares the view of other pioneer signatories that AIIB is purely an economic facility. Here it is worthwhile to note that other SCS disputants –Brunei, Malaysia, and Vietnam – are also among the prospective founding members and that even Taiwan had recently conveyed its intentions to join the Bank as well. Even Indonesia with which China also has some maritime disputes in the SCS had also applied. In fact, all 10 members of ASEAN are now among the prospective founding members. Hence, not joining will only isolate the Philippines from the fast evolving economic transformation taking place in the region, much of it driven by China’s burgeoning demand and increasing outbound investments buoyed by the accumulation of considerable surplus capital and capacity.

Moreover, not joining may also reinforce the perception held by some that the Philippines simply dismisses any initiative from the Chinese side regardless of its merits – a scenario which may adversely portray the Philippines as an obstructionist. In addition, staying away from AIIB may convey that the Philippines is allowing disputes in the political front to take the driver seat in its bilateral relations with China and is closing down all avenues for possible constructive collaboration in other fields. In contrast, joining AIIB will portray the Philippines as a rational pragmatic actor aware of its funding constraints for its infrastructure requirements and open to new windows of opportunities to address the same. Therefore, Manila’s decision to sign up last year for the Bank’s establishment can be considered as timely and full of foresight. Being a prospective founding member will allow the Philippines to play an active role in the discussions aimed at drawing the Bank’s structure, policies and processes – giving it a better voice as a direct stakeholder instead of a mere outside critic.

On the part of China, getting the Philippines on board AIIB can already be considered as an achievement – a hallmark of the Bank’s inclusiveness and its nonpolitical nature. The concerns expressed by the Philippines regarding AIIB’s governance, transparency and decision making– matters that were also raised by other states – are valid and legitimate and should be attended to as the Bank gradually takes its shape. The entry of European states in the roster immersed in more developed and mature legal and financial systems will surely help in resolving these issues. It remains speculative whether China will use its clout to influence the selection of projects to be funded as a means to apply pressure to member countries with which China may have some disputes. But considering the backlash such an action will have in the Bank’s institutional credibility and its non-political foundations, such exercise will prove to be unwise and ill-advised. It will also go against China’s pronounced policy of “no political strings attached” in its economic dealings with other states.

AIIB was seen by some as part of China’s grand strategy to challenge the postwar U.S.-led world order and as a means to integrate Asian countries ever closer to China. Whether this analysis is accurate or not is lost to many developing and underdeveloped states who would rather focus on obtaining needed funding for their domestic infrastructure projects. They would rather stay away from geopolitics and big power rivalry, but exert necessary efforts to balance and hedge – maintaining an appropriate space to maneuver as the circumstances demand it. Despite the long existence of such wellestablished international and regional lending institutions like WB, IMF and ADB, the fact remains that there is still a huge gap in terms of available infrastructure financing to satisfy the ever growing demand, especially from Asian countries. Hence, as long as AIIB will complement these already existing credit facilities, affirm the Bank’s non-political nature, and address issues relating to governance, transparency and decision-making, there is no sensible argument for the Philippines not to be part of it.

Source: www.chinausfocus.com