China Faces the Eurozone’s“Currency War”

By+JOHN+ROSS

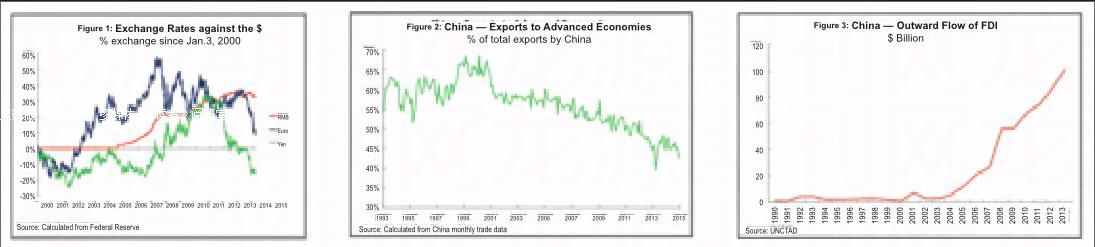

SINCE mid 2014 the Eurozone has joined what is popularly known as “currency wars” – to use terminology made famous by Brazils former finance minister Guido Mantega. Between the beginning of June 2014 and the beginning of March 2015 the Euros exchange rate dropped by 18 percent against the US dollar. The Euro therefore followed the same path of sharp devaluation earlier pioneered among major currencies by Japans yen – the exchange rate of which fell by 33 percent against the dollar between November 2012 and the beginning of March 2015 under the impact of “Abenomics.” The currencies of major developing countries, such as India and Brazil, also sharply declined against the dollar in the last two years.

In assessing the impact on China of this Euro currency move it is not important whether the devaluation was a deliberate policy objective or merely a side effect of the European Central Banks move towards Quantitative Easing (QE). The effect is the same whether the aim was Euro devaluation or not. Eurozone exporters benefit from this devaluation while exporters to the Eurozone face greater pressure.

The resulting sharp rise in the dollars exchange rate, against both yen and Euro, had negative effects on U.S. exports by the end of last year. Taking a three month average, to eliminate short-term fluctuations, the year-onyear growth of U.S. goods exports fell from 4.3 percent in May 2014 to 0.7 percent in December. With such low growth rates Obamas goal of doubling U.S. exports is out of reach.

In contrast to major devaluations of the Euro and yen, the decline in the exchange rate of Chinas currency, the RMB, against the dollar has been small. Since the RMBs all-time high against the dollar, in January 2014, Chinas exchange rate has fallen slightly by under four percent.

These currency trends are shown in Figure 1, which sets them against the background of longer-term exchange rate movements since 2000.

It is important to examine the implications of this sharp Euro devaluation for China. The earlier yen devaluation had a certain limited negative impact on Chinas exports – the proportion of Chinas exports going to Japan fell from about eight percent at the beginning of 2012 to six percent by the beginning of 2015. But Japan is a much smaller export market for China than the European Union (EU), of which the Eurozone is the core. The EU and U.S. are Chinas largest export markets – each accounting for around 16 percent of Chinas exports. Europe is similarly important for Chinas outward Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). The consequences of Euro devaluation are therefore potentially more significant for China than was the yens earlier decline.endprint