Capricious Liu Wei

by+Chen+Ling

The 798 Art District, born of an abandoned factory complex, was once a utopia for artists pursuing their dreams in Beijing. Today, however, it has transformed into a popular tourist attraction on par with the Great Wall and Palace Museum (Forbidden City). The constant stream of visitors has squeezed many artists out in favor of other peripheral urban areas such as Heiqiao and Huantie. Liu Wei is one of them. Liu was born in 1972 in Beijing and graduated from the China Academy of Art in 1996. Considered a top student in academic and institutional circles, Liu believes becoming a master requires much more than excellent painting. Hes not a fan of the methods Chinese artists used in 1960s, as exhibited in the work of internationally acclaimed Zhang Xiaogang and Wang Guangyi, who associated art with political issues.

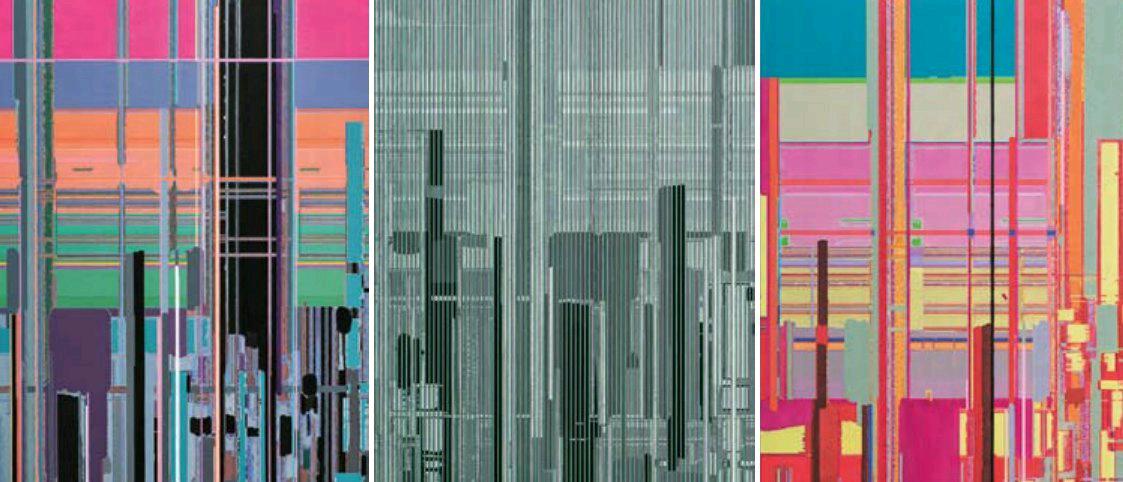

Back during the “post-sense sensibility” trend in the 1990s, Liu and his peers exhibited work in underground spaces or unfinished shopping malls. Not until 2009 did he first show work at Ullens Center for Contemporary Art (UCCA), when he was featured in the exhibition Breaking Forecast: 8 Key Figures of Chinas New Generation Artists. In 2015, as he returns to UCCA to hold a solo exhibition, Liu Wei: Colors, he does so as a world famous artist. “Liu Wei is one of the leaders of his generation,” declared Michelle Yun, curator of modern and contemporary art at New Yorks Asia Society Museum. “He can negotiate the domestic art scene within China while also holding his own in this larger international milieu.”

As art critic Gunnar B. Kvaran remarked in a recent essay, Liu ranks among the first generation of “post-Mao children.”Having come of age in the dynamic period of rapid urbanization and artistic blossoming preceding the Beijing Olympics, Liu is heavily influenced by the instability and fluctuation unique to 21st-Century China, particularly in terms of its physical and intellectual landscape.

Before the opening of his exhibition, Liu was asked to train guides wearing Tshirts reading “ask me.” Within minutes, he rushed around the gallery: “Here I wanted the sense of a forest,” “This symbolizes endless extension,” “I dont think I need to explain this piece,” “Thats about it.” His ultra-concentrated methods made the “ask me” shirts a bit pointless. “I am a visual artist and I just make art according to my feelings,” Liu explains. He tries to align himself with formalism while breaking from the label of “conceptual artist.” “When we are guiding spectators, how should we interpret your ideas?” one of the guides asked. “However you want!” Liu answered.

In the foyer of UCCA is Lius Love it, Bite it, resembling a miniature capitol or museum complex or other “authoritative institution” composed of yellow clay. The texture of the work is so glaringly fragile that it seems it could melt in your mouth. Liu began working on this Dog Chew series in 2007.

A painting with gradient colors graces the entrance to the exhibition hall, leaving only a narrow passage for visitors to pass through. Army green mattress-like patches, steels wrapped in canvas with names of state-owned manufacturers and pieces of wood (actually wood-textured sponges) compose Enigma, which is reminiscent of the jungle as well as Lius early decision to give up a stable job to brave his way through the “artistic jungle.”

Past Enigma is a heavy steel screen, dividing the space into two parts. On the left are many mirrors reflecting spectatorsfaces many times, which does not inspire fear because most people are so familiar with the glass on buildings in big cities. On the right is a pile of geometric shapes resting precariously against the wall, reminiscent of some of Beijings odder buildings. Its title card indicates the work is composed of books.

“Cut!” Liu exclaims. “What I have always been doing is ‘cutting unnecessary things.” A savvier path to “nobility” is to veer focus to a variety of seemingly cheap and abandoned materials such as door frames collected from demolished houses, furniture found in a flea market, dog chew toys, empty tins and used yellow sponges.“I am never inspired by social issues,” Liu insists. “I also employ new canvas and door frames and never think about what they are supposed to express. I am just a visual artist. I choose materials solely based on construc- tion considerations. Moving the audience to tears or arousing their empathy is not my job.”

When Lius “Colors” exhibition opened at UCCA, Gao Shiming, professor at Chinese Academy of Art, called the exhibition the most capricious event in the history of UCCA. “‘Post-sense sensibility, in my opinion, rejects conceptual art, which simply and directly judges social issues weighing right and wrong,” noted critic Pi Li.

“I would caution most artists to keep distance from fetishism because it is so easy to fall into it during creation, but Liu Wei succeeds with it,” opines Catherine David, Deputy Director of Centre Georges Pompidou. “I always say dont think that just because you took a picture of a homeless person lying in a gutter, you displayed the misery of the world and your picture was meaningful. I have always focused a more discerning eye on this kind of work in my curatorial career.”

China Pictorial2015年4期