Evolution of a Dining Hall

by+Song+Baozhen

A Chinese saying declares that“food is heaven.” For centuries, dining has been the centerpiece of daily life in China. The choice of what to eat and how to eat was traditionally a private matter. However, Chinese dining habits have evolved and become more collectivized since the countrys industrial revolution, especially with the emergence of dining halls in stateowned enterprises when the country implemented a planned economy.

The dining hall became the modern campfire to sit around while enjoying delicacies and flavors from all over the country and from every era.

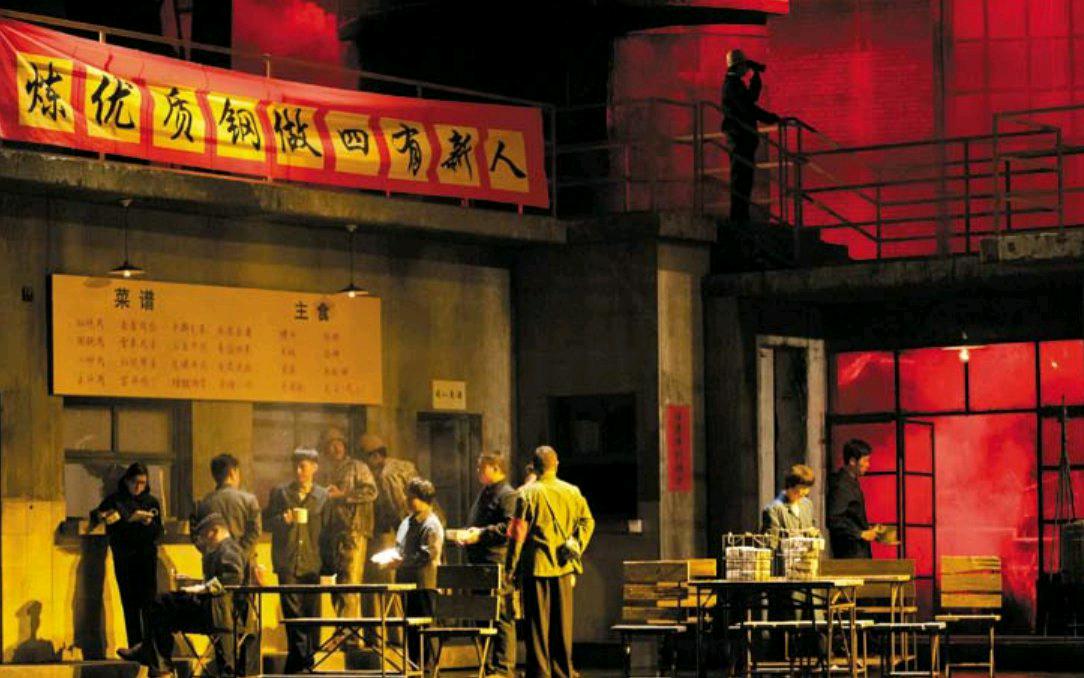

And so in February 2015, a play titled The Dining Hall by Yuan Bin, directed by Gu Wei, was staged by Beijing Peoples Art Theatre (BPAT).

Based on the true story of a large-scale state-owned steel plant, the drama depicts the same dining hall across different eras: the 1980s, 1990s, and as recently as 2010, evidencing the changes of life and evolution of Chinese workers riding the tide of economic reform and opening-up.

Valuable Research

An original full-length drama, The Dining Hall contrasts many of BPATs previous plays, which often took place amidst hutongs (small alleys typical in Beijing). It particularly focuses on workers, who often suffered the growing pains of marginalization during transitions.

After the success of its many hutongoriented plays, BPAT has blazed a new trail in staging dramas against an industrial backdrop to reflect the changes of the times.

The Dining Hall is heavily reminiscent of world-renowned Teahouse, the global hit that has toured Europe, America, and Southeast Asia since the 1980s.

Over the last few years, many theater artists have toiled away attempting to reach or surpass the success of Teahouse, evidenced in the theatrical structures and relationships between characters in BPAT plays such as Xiao Jing Hutong, The Bathroom, and The Top Restaurant.

Hearkening to and referencing masterpieces is not taboo if the audience is presented novel work. The Dining Hall shares many structural similarities with Teahouse, which is more like a group play with scattered, dotted events. The Dining Hall depicts the herd mentality, logic, and human feelings about daily routines.

Teahouse, however, reviews history from a critical perspective, jumping out of the olden days when it was written, contrasting how characters in The Dining Hall have overcome obstacles through retrospection on history as it traces an ongoing story in the new era of China experiencing the industrial revolution.

Too Fresh for Judgement

The Dining Hall depicts Chinas economic development and the transformation of state-owned enterprises over the last 30 years.

The first act depicts Chinese workers enjoying subsidies from the State after the country implemented the planned economic system. It was common to see diners taking steamed bread back home, so supply always fell short of demand in the dining hall.

The second act illustrates the restructuring of the enterprise in the 1990s, when ownership of the dining hall shifted from collectively-owned to privately-contracted, resulting in changing patterns in the dining hall: Some still maintained the egalitarian practice of “everybody eating from the same big pot,” while others began enjoying specialized services. The fate of workers changed as well: Some get promoted; others were laid off.

The third act jumps to the year 2010, when the dining hall goes dark before it is torn down and replaced by a food street. The factory deteriorates into industrial ruins.

The Dining Hall depicts a group of 20 characters who represent the working class throughout Chinas reform.

Plain and kind, Yong Jiu works diligently during the era when the factory is owned by the state. He sticks to strict morals and hates receiving a greater share of the earnings when the factory implements shareholding system, which wins the heart of Xiao Juan, his coworker.

Misanthropic “Big Guy” is a veteran of the Counterattact Against Vietnam in Self-Defense (1979), which scarred him. He gets laid off and ends up riding a rickshaw to subsist.

Unemployed young man Wu Zi heads to Shenzhen seeking fortune and ends up using drugs and blowing all his money because he completely loses his direction.

Liu Shulin, a recent college graduate, wins promotions and big paychecks at breakneck speed by sucking up to his supervisors. Nevertheless, he worries about falling from grace at any moment and never enjoys a second of inner peace.

Zhang Beiwen assumes an important post in the factory, then resigns to start his own business. It fails, however, and he eventually makes a living driving a taxi.

An old artisan transforms into an inheritor of Intangible Cultural Heritage in the new century as his years of struggling for survival by collecting scraps are finally rewarded.

The Dining Hall traces changes of the times in China and focuses on the complicated transformations of Chinese lives over dozens of years: from self-reliant business to the injections of foreign capital, from indistinguishable eating to variations between poor and rich, from workers stuffing their pockets with steamed bread due to shortages at home to surplus and “specialists” promoting mung beans in the name of good health, and from speculators and profiteers of small commodities to investors discussing stock futures.

As well as affirming fruits brought by the industrial revolution and economic reform and opening-up, The Dining Hall dialectically reflects workers during the“throes” of reform. Nostalgia for workers in urban China is common these days.

As for the acting, The Dining Hall follows realistic artistic tradition, focusing on presenting genuine flavors of various eras.

In terms of set design, the artists produced an aesthetic perception of rituality. The curtain rises with the song, “We Workers Are Powerful,” an icon of the early stage of industrial China during state ownership. The stage is covered by a giant steel slab. Two workers strike it three times, and the story begins as it is lifted.

Before the curtain drops, a group of visitors tour the relics of the factory, which are overgrown with weeds. Yong Jiu and his wife continue to sell steamed buns there. Through the small buns, people seem to enjoy a taste of life which, however, remains far from a true reflection of the acceleration of time, undercurrent of desire, complex moral choices, and principles of social justice.

What The Dining Hall leaves for the audience is a complicated space still too fresh to be judged.