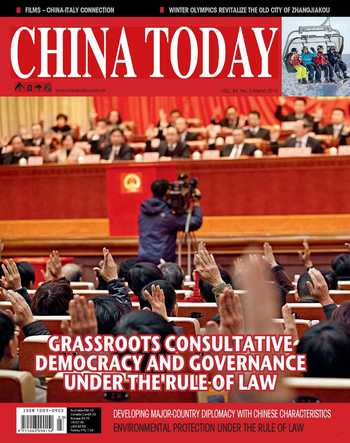

Democratic Consultation at the Grassroots

By XU HAO & AN XINZHU

EVERY afternoon, Zhang Sisi, born in 1991, heads out to visit local vil- lagers and collect their opinions on village public affairs. Its part of her daily routine. Since September 2014, Zhang has worked as an assistant to the Zhouliangzhuang Village Committee of Baodi District, Tianjin. In addition to advising villagers on policies, issuing certificates and filing information, one of Zhangs important duties is to convey villagers appeals to the village committee and subdistrict office. “By gathering locals opinions, we can have a proper, well-informed discussion before making important decisions,”Zhang said. In fact, every administrative village in the subdistrict has a village affairs assistant like Zhang.

In June 2013, amid the progress of grassroots consultative democracy nationwide, Baodi District established the village-level democratic consultation council mechanism, allowing people to extensively and directly participate in

the decision-making, management and supervision of village affairs. The village affairs assistant thus facilitates democratic consultation.

Consultative Democracy

In Baodi District, decisions regarding major village affairs, in principle, are based on democratic consultation council discussions.

Land is a big issue in rural areas. With the development of modern agriculture, land circulation – whereby farmers transfer their land-use rights so that dispersed farmland can be centralized for intensive mass agricultural production – has become a trend. However, it is not easy in practice. “Some farmers worry that their land is being taken away,” said Li Guangen, Party secretary of Zhouliangzhuang Village.

The process of land circulation in Zhouliangzhuang Village was full of twists and turns. “Some villagers, who want to go outside and work as migrant workers, first talked to us (the ‘five-aged council). They planned to transfer their land-use rights. We then presented their opinion to the village committee and Party branch committee. However, the democratic consultation convened by the two committees found many different opinions. So it fell to us to convince the doubters of the economic benefits of transferring their land-use rights, and they eventually agreed,” villager Zhang Xueyi said.

Seventy-year-old Zhang is a village representative and a member of the village affairs supervisory committee. He is also a member of the “five-aged council,”an advisory panel consisting of prestigious and qualified senior teachers, veterans, cadres, Party members and model workers that play a special role in consultative democracy. Such councils have been in place in Zhouliang Subdistrict since 2012.

Some 30 people from village committee, Party branch committee, the fiveaged council and other representative groups attend democratic consultation meetings. In addition to these fixed members, any locals aged 18 or above can participate. If needed, officials or staff workers of the local government and other related people can also join in for on-site supervision and guidance.

“By inviting highly respected villagers and the parties involved, everyone can voice ones opinion. On this basis, a final decision will be formed, which will give consideration to the interests of all parties and satisfy everyone,” said Li Guangen.

When Tianxingzhuang Village implemented land circulation, several households were not in favor. Having worked as the village Party secretary for 18 years, Wang Xuelan was familiar with the methods of rural work. She and her colleagues visited the objecting farmers to find out more about their concerns.“We promised to provide them with training and help them to find jobs in urban areas. Their worries about future dispelled, they finally agreed,” said Wang.

“Simply speaking, consultative democracy refers to dealing with problems through discussion,” explained villager Li Jingquan.

Institutionalizing Established Practices

Mass consultation has always been something of a custom in rural Baodi. According to Li Guangen, mass consultation has been carried out for several years in his village. “It was not always institutionalized, but the discussion of village affairs has always been transparent, laying a solid foundation for official mass consultation. Today, based on the consultative democracy system, handling village affairs has been streamlined.”

Wang Xinsheng, head of the Department of Philosophy at Nankai Univer- sity and a member of the universitys research group on consultative democracy, pointed out: “Traditional Chinese philosophies call for harmony and consultation. If we were to separate the wheat from the chaff and adapt these philosophies to the modern idea of rule of law, civic virtue would be greatly enhanced.”

In October 2013, guidelines on carrying out grassroots consultative democracy were formulated and began to be implemented in Baodi District, which marked the start of institutionalizing consultative democracy in the countryside. According to the guidelines, affairs discussed by a village-level democratic consultation council are classified into major issues and general issues. Village-level major issues may include village self-governance rules, enactment and revision of village regulations and non-government agreements, local development programs, construction planning and relevant adjustments, an-nual working and budget plans, land transfer, and land requisition compensation, to name a few. Issues like recommendation of model residents, applications for village-level subsidies and dispute settlements are listed as general issues.