The risk of wound infection after simple hand laceration

Department of Emergency Medicine, Downstate Medical Center, State University of New York, Brooklyn, NY, USA

The risk of wound infection after simple hand laceration

Gholamreza S Roodsari, Farhad Zahedi, Shahriar Zehtabchi

Department of Emergency Medicine, Downstate Medical Center, State University of New York, Brooklyn, NY, USA

BACKGROUND:This prospective observational study aimed to determine the infection rate of simple hand laceration (SHL), and to compare infection rates between patients who were prescribed antibiotics and those who were not.

METHODS:The study was performed at two urban hospitals enrolling 125 emergency department (ED) patients with SHL. Exclusion criteria included patients with lacerations for more than 12 hours, immunocompromized patients, patients given antibiotics, and patients with gross contamination, bites or crush injuries. Wound infection was def ned as clinical infection at a follow-up visit (10–14 days) or wound was treated with antibiotics. Patient satisfaction was also measured using a visual analogue scale 1–10, asking the patients about wound appearance. Demographic data and wound characteristics were compared between the infected and non-infected wounds. The infection rates were also compared between patients who received prophylactic antibiotics and those who did not. The results were presented with medians and quartiles or percentages with 95% conf dence intervals (CI).

RESULTS:In the 125 patients with SHL [median age: 28 (18, 43); range: 1–102 years old; 36% female], 44 (35%, 95%CI: 27%–44%) were given antibiotics in the ED. Wound infection was reported in 6 patients (4.8%, 95%CI: 2%–10%). Age, gender, history of diabetes and wound closure were not associated with wound infection (P>0.05). The infection rate was not signif cantly different between patients with or without antibiotic prophylaxis [7% (3/44), 95%CI: 2%–10% vs. 4% (3/81), 95%CI: 1%–11%,P=0.66]. Patient's satisfaction with appearance of infected and non-infected wounds were signif cantly different [7.5 (6, 8) vs. 9 (8, 10),P=0.01].

CONCLUSION:Approximately 5% of simple hand lacerations become infected. Age, gender, diabetes, prophylactic antibiotics and closure technique do not affect the risk of infection.

Wounds; Injuries; Wound infection; Hand lacerations

INTRODUCTION

Hand injuries are commonly seen in the emergency department (ED) and constitute approximately 8% of trauma-related ED visits.[1]Despite the high prevalence, management of simple hand lacerations has not been standardized and the literature on infection rate, risk factors for infection, and utilizing prophylactic antibiotics to prevent infection in simple hand lacerations (hand lacerations distal to the radial carpal ligament that do not involve any special structures such as bones, tendons, vessels, or nerves) is scarce.[2]In addition, physicians' approach to management of simple hand lacerations particularly relative to administration of prophylactic antibiotics has been shown to be varied.[1]This study was designed to identify the incidence of wound infection in ED patients with simple hand lacerations while detecting host and wound characteristics that place patients at increased risk of infection.

METHODS

This prospective observational study was conducted at two urban academic centers. The joint institutional review board approved the study. Informed writtenconsent was obtained from all patients prior to enrollment.

Study setting and population

Kings County Hospital Center is a level 1 trauma center with annual ED census of approximately 150 000. Downstate Medical Center has approximately 70 000 ED visits annually. A convenience sample of patients was enrolled from September 2010 to July 2011.

Study protocol

Data collection was performed by trained data abstractors (research associates). Adult ED patients (≥13 years old) with simple hand lacerations were enrolled in the study. Patients with the following conditions were excluded: 1) immunocompromized patients (cancer, chemotherapy, transplant, HIV/AIDS); 2) current or recent (within two weeks) use of any antibiotics; 3) gross infection as determined by the treating clinician; 4) grossly contaminated wounds by dirt or other foreign substances (e.g. tar, oil, etc.); 5) bites (e.g. dog, cat or human); 6) crushed injury; 7) lacerations inf icted more than 12 hours prior to ED visit.

Patients with simple hand lacerations who met the inclusion criteria were brought to the ED.Written informed consent was obtained from the patient and demographics and medical history were recorded. Wound characteristics such as location, length, shape, presence or absence of foreign body and method of closure were documented. Whether prophylactic antibiotics were given was decided by the attending physician.

Outcome measures

Wound infection was def ned as clinical infection by primary care physician at follow-up visit (10–14 days) or wounds requiring antibiotics after initial visit to the ED. The cosmetic appearance of the wound was determined by a visual analogue scale (VAS) at 30 days after the initial ED visit. At that time the patient selected the cosmetic appearance of the wound on a scale of 1–10 (1 for worst and 10 for best satisfaction) over the phone.

Statistical analysis

Data were presented as medians and 25%–75% quartiles for continuous variables and percentages with 95% conf dence interval for proportions. Wound and host characteristics between the infected and non-infected wounds were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables and Fisher's Exact test for categorical variables. The significant level was set at 0.05 (two-tailed test). Additional group comparisons were performed with Fisher's exact test for the outcome of wound infection between patients with and without prophylactic antibiotics respectively. Visual analogue scale (VAS) scores representing patient's satisfaction with the appearance of their wounds at 30 days were compared between the infected and non-infected wounds and between those who received prophylactic antibiotics and those who did not, using the Mann-Whitney U test. All analyses were performed with SPSS software (version 20.0, 2011, 1997. SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA).

RESULTS

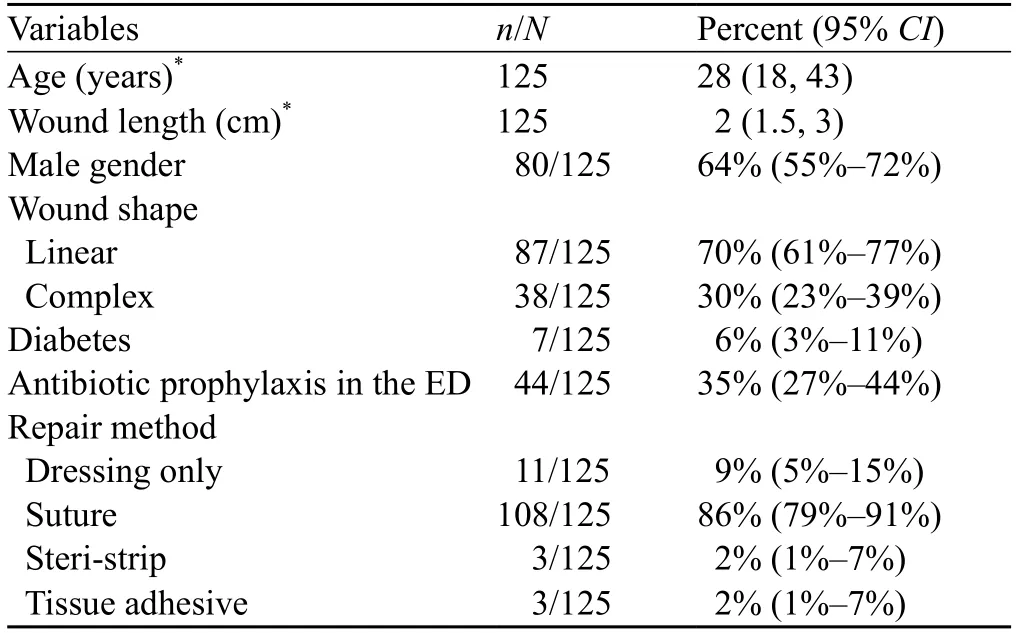

A total of 125 patients were enrolled in the study [median age: 28 (18, 43), range: 1–102 years]. Sixtyfour percent (95% CI, 55%–72%) of the patients were male. 112 (90%) patients were followed up for 30 days. The baseline characteristics of the enrolled patients were listed in Table 1. Wound infection occurred in 6 (4.8%, 95% CI: 2%–10%) of the 125 patients. ED physicians prescribed antibiotic prophylaxis for 44 patients (35%, 95% CI, 27%–44%) at initial visit. The most commonly prescribed antibitics were cephalexin (36 patients, 82%), amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (6 patients, 14%), and others (2 patients, 4%).

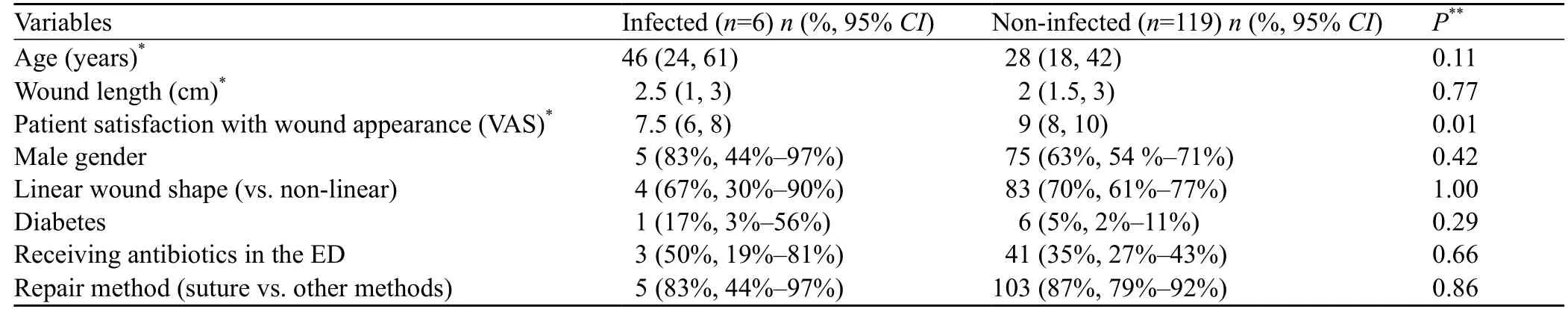

Comparison of the infected and non-infected wounds was presented in Table 2. The infection rate was not signif cantly different between the patients with antibiotic prophylaxis and those without antibiotic prophylaxis (3 patients, 95% CI: 2%–10% vs. 4%; 2 patients, 95% CI: 1%–11%, P=0.66).

Patient's satisfaction with wound appearance of the infected and non-infected wounds were significantlydifferent [median 7.5 (6,8) vs. 9 (8,10), P=0.01, respectively]. The difference between VAS scores comparing patients who were given prophylactic antibiotics in the ED with those who were not given prophylactic antibiotics was also statistically signif cant, favoring no prophylactic antibiotics [median VAS: 8 (7, 9) for prophylactic antibiotic group vs. 9 (8, 10) for no prophylactic antibiotic group, P=0.032].

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the enrolled patients

Table 2. Comparison of wound characteristics in patients with and without wound infection respectively

We also compared the characteristics of patients who were precribed antibiotic prophylaxis in the ED (n=44) with those of the patients who were not precribed antibiotic prophylaxis (n=81). Patients who received prophylactic antibiotics were older [median age: 40 (quartiles: 28, 51) vs. 28 (quartiles: 16, 48), P: 0.033] than those who did not receive prophylactic antibiotics. Patients who received prophylactic antibiotics were more likely to have contaminated wounds [6/44 (14%) vs. 0/81 (0%), P: 0.02]. No significant difference was observed between the two groups when gender, wound shape, wound length, repair method, and history of diabetes were compared.

DISCUSSION

In this study we investigated the prevalence of wound infection after simple hand lacerations and the factors affecting the prevalence. Few studies on the infection rate of simple hand laceration have been mostly focused on the benefits of prophylactic antibiotics.[3–6]The infection rate ranges from 5% to 32%,[3–7]which originates from the differences in study designs, types of antibiotics used, definition of wound infection, and follow-up rate.[2]The infection rate in our study cohort falls within this range (5%).

Because of the discrepancy of infection rates, the data on the role of antibiotics in preventing infection in simple hand lacerations provide conflicting results.[2]The studies are generally old, have small sample sizes, and are rife with methodological f aws.[3–6]In the present study, we did not observe any statistical difference between those who received prophylactic antibiotics and those who did not. However, in the absence of a rigorous randomized control trial, assessing the role of prophylactic antibiotics is not possible. The low infection rate in our study indicates that the sample size for such trial would be very large.

Various studies[8–10]have reported that the factors might increase the risk of infection in patients with simple hand laceration. Studies on the association of patient's age, number of sutures, length of laceration, presence of diabetes, and wound age with a higher risk of infection have produced conflicting results.[7–10]Among these factors, wound age has received much more attention. It was believed that there exists a "golden period" beyond which the risk of infection signif cantly increases, a recent systematic review ruled out the presence of association between any wound age cut off and a higher risk of infection.[11]Because of a small number of patients with wound infection, we were not able to perform the logistic regression analysis that was originally planned to identify factors that could predict wound infection in our study cohort. However, our univariate analyses did not identify any wound or host characteristics that were associated with a higher risk of infection.

According to the study by Singer et al,[12]from patients' point of view the most important factor secondary to wound infection is the appearance of wound after repair. Having this in mind, we assessed the self-reported patient satisfaction with wound appearance in patients with and without infection as well as those with or without prophylactic antibiotics using a VAS scale. It was not surprising that the infected wounds had a lower satisfaction score. However, in our study there was a negative association between patient satisfaction and antibiotic prescription. This could be related to the likelihood that patients with more severe injuries and ahigher risk of bad scarring were more likely to receive antibiotics in the ED.

LIMITATIONS

The convenience sampling method in our study exposes our study results to sampling bias. It is possible that ED physicians did not refer patients with a higher risk of infection for enrollment.

This was a prospective observational study, which was not designed to specif cally address the question of whether antibiotic prophylaxis has any role in preventing wound infection in simple hand lacerations. There is a clear need for a large multicenter randomized control trial to shed light on this issue.

Because of the small number of patients with wound infection, we were not able to identify factors associated with a higher risk of infection.

In conclusion, wound infection rate after repair of simple hand laceration is low. Wound infection is associated with lower patient satisfaction with wound appearance at 30 days post injury.

ACKNOWLEDEMENT

The authors would like to thank Amr Badawy, DO, and Khaled Hassan, MD for their contribution to the study.

Funding:This study in part was funded by a medical student grant ($2500) by the Emergency Medicine Foundation.

Ethical approval:The joint institutional review board approved the study.

Conf icts of interest:The authors have no commercial associations or sources of support that might pose a conf ict of interest.

Contributors:Roodsari GS proposed the study. All authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study, and approved the f nal manuscript.

1 Zehtabchi S, Yadav K, Brothers E, Khan F, Singh S, Wilcoxson RD, et al. Prophylactic antibiotics for simple hand lacerations: Time for a clinical trial? Injury 2012; 43: 1497–1501.

2 Zehtabchi S. The role of antibiotic prophylaxis for prevention of infection in patients with simple hand lacerations. Ann Emerg Med 2007; 49: 682–689.

3 Roberts AH, Teddy PJ. A prospective trial of prophylactic antibiotics in hand lacerations. Br J Surg 1977; 64: 394–396.

4 Beesley JR, Bowden G, Hardy RH, Reynolds TD. Prophylactic antibiotics in minor hand injuries. Injury 1975; 6: 366.

5 Grossman JA, Adams JP, Kunec J. Prophylactic antibiotics in simple hand lacerations. JAMA 1981; 245: 1055–1056.

6 Dire DJ, Coppola M, Dwyer DA, Lorette JJ, Karr JL. Prospective evaluation of topical antibiotics for preventing infections in uncomplicated soft-tissue wounds repaired in the ED. Acad Emerg Med 1995; 2: 4–10.

7 Lammers RL, Hudson DL, Seaman ME. Prediction of traumatic wound infection with a neural network-derived decision model. Am J Emerg Med 2003; 21: 1–7.

8 Caro D, Reynolds KW. An investigation to evaluate a topical antibiotic in the prevention of wound sepsis in a casualty department. Br J Clin Pract 1967; 21: 605–607.

9 Roberts AHN, Teddy PJ. A prospective trial of prophylactic antibiotics in hand lacerations. Br J Surg 1977; 64: 394–396.

10 Roberts AHN, Roberts RIH, Thomas IH. A prospective trial of prophylactic povidone iodine in lacerations of the hand. J Hand Surg 1985; 10-B: 370–374.

11 Zehtabchi S, Tan A, Yadav K, Badawy A, Lucchesi M. The impact of wound age on the infection rate of simple lacerations repaired in the emergency department. Injury 2012; 43: 1793–1798.

12 Singer AJ, Mach C, Thode HC, Hemachandra S, Shofer FS, Hollander JE. Patient priorities with traumatic lacerations. Am J Emerg Med 2000; 18: 683–686.

Received July 1, 2014

Accepted after revision January 11, 2015

Gholamreza S Roodsari, Email: Gholamreza.roodsari@downstate.edu

World J Emerg Med 2015;6(1):44–47

10.5847/wjem.j.1920–8642.2015.01.008

World journal of emergency medicine2015年1期

World journal of emergency medicine2015年1期

- World journal of emergency medicine的其它文章

- The role of regulatory T cells in immune dysfunction during sepsis

- Instructions for Authors

- Lingual angioedema after alteplase treatment in a patient with acute ischemic stroke

- Regulatory effects of hydrogen sulf de on alveolar epithelial cell endoplasmic reticulum stress in rats with acute lung injury

- Relationship between intubation rate and continuous positive airway pressure therapy in the prehospital setting

- Acute intoxication cases admitted to the emergency department of a university hospital