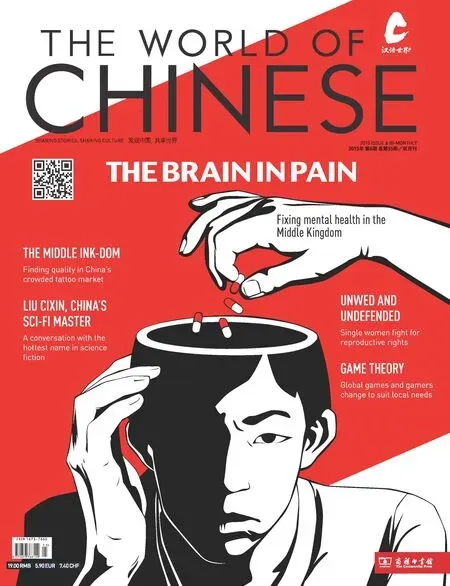

GAMETHEORY

BY DAVlD DAWSON

GAMETHEORY

BY DAVlD DAWSON

The sophisticated ways in which China and the US are transforming games for each other

游戏的世界里,入乡就要随俗。

为了让海外玩家买账,中国和美国的游戏开发者都操碎了心。

Somewhere along the way to China, the skeletons in World of Warcraft mysteriously vanished.

Most were quick to assume that the change to the world’s largest Massively Multiplayer Online Role Playing Game (MMORPG) was the result of edicts from China’s censorship bureaus; after all, they had been known to make bizarre demands from time to time, such as banning time travel from TV or banishing the cleavage of Tang Dynasty royalty.

This, however, was only a half-truth. While regulations do discourage the promotion of superstition, the game developers, facing an expensive, potentially lengthy and risky approvals process to get into the Chinese market, most likely decided to take the safe route and axed their own skeletons before players or censors even had the chance.

It was one startling example of the vagaries of computer game localization—a process in which game developers tweak their product to suit a foreign market, which has become a multi-billion dollar international business and when done well involves careful analysis of everything from design preferences, storyline tweaks, political and cultural expectations, and above all else figuring out what people from different cultures will and won’t pay for.

With China and the US now representing the world’s largest game markets and producers, developers on both sides of the Pacific are trying to find ways to tap into each other’s markets.

It’s an extraordinarily difficult endeavor in a new and rapidly evolving industry. MMORPGs, mobile platform games, and firstperson shooters are all incredibly different beasts with different markets and needs, and the industry itself has transformed from mere translation to something else entirely.

lll

US

TR

AT

lO

N BY

GA

OFEl

CASH ClASH

An apocryphal tale circulates among the game development community in Beijing. The CEO of a well performing game company scolded his developers by saying: “We are not here to make great games.”

True or not, it’s a powerful illustration of the tension between sometimes idealistic developers and their profit-oriented masters. This tension is hardly unique to China, but there are certainly aspects that make the “profit” part of the equation more intense. The dizzying speed at which games are churned out by Chinese companies, often without much originality or customer support, has meant China and other East Asian companies have had to be at the cutting edge of monetization efforts for decades.

Certainly, stepping inside Elex, a stone’s throw from Beijing’s tech district, it is easy to see that Chinese companies have stepped powerfully onto the global stage. Elex created Clash of Kings, one of the top games internationally on Android’s app store. It’s a powerful achievement for a Chinese company and vindicates their approach: create an international success first, then focus on the Chinese market.

From the outset it was internationally focused. Initial challenges included international payment systems (no mean feat given controls on international monetary transfers) and partnering with other companies. CEO Tang Binsen found himself on Global Entrepreneur’s list of Business Elites under 40 as the company rapidly expanded.

In one way the company has retained the strengths of the Chinese approach; its aggressive but nuanced approach to monetization has paid off, with over 10 million USD in turnover each month, and the company has approached it in a manner far that has proven to be far more sophisticated than its contemporaries.

But those contemporaries don’t necessarily have to be adept at localization themselves. The industry has spawned its own specialist companies which can be choosy about which titles they select for localization.

Matt Leopold is Business Development Manager with Yodo1, a company focused on bringing Western mobile games to China. He points out that monetization is a delicate endeavor. “It depends on the game, but often it’s whether it is monetized earlier rather than later. At certain points it’s whether you are required to buy an item or wait a long time. These are decisions we have to make to ensure it caters to the Chinese players.”

When it comes to payment, there are some key differences between Chinese players and Western ones. “In some cases we have had to convert games from a payment framework where you pay to download, to a free-to-play framework with in-app purchases,”Leopold points out. “This has been

ClASH OF KlNGS lS CURRENTlY

EXPECTED REVENUE FROM MOBllE GAMES lN 2015

菊花属于多年生长草本植物,是中国传统十大名花之一,适应性强,分布比较广,具有很好的观赏价值。庆阳地区是菊花重要的种植地区,主要是以盆栽形式用于观赏。在菊花的繁殖方式上主要是以嫩枝扦插为主。笔者从实践中对菊花栽培管理技术进行分析,现介绍如下。

36more of a common model in China, but you are starting to see more acceptance of paid games.”

If a developer pushes too hard on monetizing a game it can turn gamers off entirely, whether they are from China or the West. As a general rule of thumb, Chinese gamers appear far more willing than their Western counterparts to tolerate fairly restrictive in-app purchases, paywalls, and payment for necessary booster items, however they are much less willing to pay upfront for a game.

Joshua Dyer, a former game localization specialist who worked with Beijing-based companies to localize their MMORPGs to Western markets, points out that this has created online worlds which might come across as off-putting to some Western gamers. “One characteristic of a lot of Chinese MMORPGs is that basically they are a class society. The free players get to play and have fun, but they’re basically cannon fodder for the rich players. The rich players spend money and become powerful and get to live out these fantasies of ruling a kingdom. That model doesn’t translate well to Western gamers.”

Aggressive monetization can push Chinese gamers over the edge as well. A 2007 Southern Weekly report profiled Lu Yang, who had been a powerful player and leader of a kingdom in MMORPG ZT Online. After becoming addicted to “lucky chests” which have a tiny chance of granting powerful items (a common ploy in Chinese games, and increasingly Western ones), Lu was among the gamers annoyed when the game both restricted the trade of items (which could only be used by specific character classes, making many items useless) to boost purchases, and shattered alliance networks to encourage wars, also to boost purchases. Virtual protests erupted, with characters massing in an area to peacefully express opposition. Lu Yang found her complaints against the “system” were being censored, then her character was thrown into a virtual gulag by the game, where she was killed over and over by lower-level characters.

In contrast, 2009 game Runes of Magic was localized to English and European languages and adopted a more open approach.

“They did a really good job of balancing so the free players had a full gaming experience and they didn’t feel bullied and beaten up by the rich players,” Dyer points out.

A lot of Chinese companies have had success in localizing these games for overseas markets in terms of profitability, but not as much in terms of recognition. “They make English localized versions of the games, they don’t necessarily need to have a lot of people play it because they develop games so cheaply and quickly in China compared to the West,” Dyers says. “If they do really good marketing they can get people to sign up, and they’re very good at monetizing—lots of incentives to put in small amounts of money, putting in a few extra bucks.”

It helps that Chinese gamers are used to transactions of more minor significance, with purchase options as low as one RMB.

“But they don’t retain a loyal following, they don’t necessarily have the depth, quality, or customer support. But some of these games have made quite a killing in the short term.”

MOBllE GAMERS BY THE END OF 2015 lN CHlNA

MORE THAN 50 % OF THE CHlNESE MOBllE GAME MARKET

THlS CREATES A PARTlCUlARlY 21ST CENTURY FORM OF lNTERCUlTURAl TRANSFER WHERE A CHlNESE COMPUTER GAME MAY BE PlAYED lN ENGllSH BY RUSSlAN PlAYERS VlA AN

AMERlCAN SERVER

One example is Evony—a game which attained a lot of fame but many would argue for all the wrong reasons. Deciphering whether it is a “Chinese”game is difficult: Registered in US tax haven Delaware and with a tone reminiscent of a cheaper version of the Civilization games, one may think it was a Western game, were it not for the maze of holdings and ownership records that stretch across Hong Kong and to the tax haven the Marshall Islands, as well as studios in Qingdao, Shandong Province. There was also a Guardian article citing other game developers and bloggers as saying the company was linked to a Chinese company UMGE, which in turn was tied to “virtual gold farming”operations which paid real, albeit low, wages to people to mine gold in World of Warcraft to sell to other players.

Evony became famous not for its content, which was pronounced unoriginal by almost all reviewers, rather, it was famous for its salacious advertising which drew in players from all over the world. But eventually the buxom, scantily clad women urging prospective players to rescue the princess were no longer enough (there wasn’t even any princess aspect to the game).

For such a controversy, the game itself proved dull. The outrage and annoyance faded, and so too did the number of players.

CUlTURE SHlFT

Audiences for games localized into English may not be what you might expect. In many cases, the bulk of the audiences are not native English speakers. This creates a particularly 21st century form of intercultural transfer where a Chinese computer game may be played in English by Russian players via an American server.

Dealing with all of these cultures can be weird.

If you want to sell games to Germans, you may want to make the blood and gore green, so it doesn’t look too real and thus gets approved by German regulators more easily. In China, there are a host of cultural preferences that may affect your game. Dyer worked for one company, which made certain changes because“Chinese gamers preferred it to have exaggerated, fantasy elements. The armor had ornate protrusions coming out, to scale they would be ten feet tall. Western gamers prefer a more gritty, chunky look.”

“Part of the localization process required character redesign, so all of that is a big part of it,” Dyer says.

Generally, a company won’t redesign an entire game, it is generally easier to add expansion packs or tweak the art styles. Leopold worked on one game where they added Chinese themedholiday packs, with things like dragons and ancient Chinese characters.

On a larger scale, he was on a team which adapted the entire storyline of a game. The original plot of the sniper-themed game was essentially an exercise in street warfare without much of a key story thread.“We had our team play through it, then we rewrote the storyline from scratch to one that would more appeal to local audiences. The guy became a Hong Kong sniper trying to get his girlfriend back, completely different to the original storyline—it became more of a comic book, all based around this kind of theme.”

Leopold says that most of the time the full cultural localization process takes between two and four months, for a mobile game. For other kinds of games it can be much longer.

Wise companies focus on localization early on in the process. Even in the translation aspect, there are basic rules that often aren’t followed, with some game developers telling TWOC that it was all too common for a localization project to be decided after the game was developed rather than during the development process, when items of dialogue could be easily tagged for later translation rather than having to sort through millions of lines of code to find sometimes staggering amounts of dialogue (at much greater cost).

A rookie mistake, one would think, but one that continues to get made. “That same rule applies to art assets,” Dyer says. “That text may not be stored in the game, you may be walking down the street and there would be a storefront in Chinese, and that may have been drawn in by the artist. If that is flagged early, you can more easily extract it.”

In principle language localization may be the same between mobile games and MMORPGs, but in practice MMORPGs tend to have a lot more text, with some having over a million characters—more than a long novel.

Deciding on translated names for characters and how to summarize dialogue are key issues, as the phonetic equivalent may have certain connotations that aren’t suitable in the other language. The developers and translators working on the localization process need to be incredibly careful to ensure they are all using the same terms.

Diehard game fans themselves have also been known to localize games in cases where developers decided monetization efforts weren’t financially viable.

With massive growth predicted in mobile and PC gaming, (MMORPGs being more complicated given the massive dominance enjoyed by World of Warcraft) Yodo1 can afford to pick and choose which titles it changes. After assessing hundreds of prospective games, it selects just a few for localization. Once it decides to go with a game, there are limited releases to test the reception.

For Apple, there is the iOS store. On the Android side of things, the Chinese market is very, very different to the West. With Google’s absence the market has been fragmented into hundreds of app stores, with a few big players. Recent reports have indicated that Google is in negotiations to get its app store released in China, but there have been no concrete announcements. Depending which developer you ask, this could be transformative or Google would become just one more player in an already crowded market. Some developers say that Chinese app stores at present are plagued with problems due to people gaming their rating systems to favor certain products, giving faulty star ratings, and that Google could change this. Leopold however, tends to think that while Google may become a large player if it gains access to the Chinese market, it would be an uphill battle requiring the right support.

But whether or not Google does shake things up in the Chinese market, one thing will remain certain—game localization is only going to grow more common, and more sophisticated, with Chinese and US developers likely to gain

an ever greater share of the spotlight.