Medium and small embankment dams on permafrost:A discussion of current concepts

Rudolf V.Zhang

Melnikov Permafrost Institute,Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences,Yakutsk 677010,Russia

1 Introduction

In permafrost regions,the stability of small and medium embankment dams is largely controlled by their hydrothermal regime.The Russian building codeSNiP 2.06.05-84*(1991) provides two approaches to the design of embankment dams:

·Principle I involves preserving permafrost in the foundation throughout the construction and operation of the dam,and freezing the impervious zone before reservoir filling and keeping it frozen for the service life of the dam.

·Principle II allows the embankment to be founded on natural unfrozen materials,or the permafrost foundation to thaw to a predetermined depth before filling the reservoir;the impervious core is in the thawed condition.

Embankment dams are classified according to the selected design approach into frozen,unfrozen,and frozen/unfrozen dams:

·In frozen dams the impervious core and the foundation are maintained in a frozen state to provide a solid impermeable barrier to water.No hydraulic connection exists between the upstream and downstream sides.

·In unfrozen dams the core and foundation,as well as part of the downstream shell,are in a thawed state and allow a limited amount of seepage to provide a hydraulic connection between the downstream and upstream.Limitations on the allowable quantity of seepage depend on stability considerations and required storage in the reservoir.

·In a frozen/unfrozen dam,the two approaches are combined to form a composite structure.Refrigeration devices are used at the unfrozen/frozen interfaces.Seepage is controlled by the complex thermal configuration across and along the dam.In cross section,the relative proportion of frozen and unfrozen zones is set so that a steady thermal balance would be established,ensuring the static and seepage stability of the dam.Typically,the frozen mass comprises most of the core cross section and the downstream shell,while the unfrozen zone encompasses the foundation of the upstream shell,parts of the core and downstream shell,and the foundation beneath and down the toe.The longitudinal section consists of alternating unfrozen and frozen "windows," with the steady thermal balance maintained.There is a hydraulic connection between the upstream and downstream sides of the dam.

One more type,a seasonally freezing-thawing dam,has been identified by the present author and colleagues (Zhang,2000;Melnikov Permafrost Institute,2012).It is a seasonally operating dam in which water tightness is provided during spring floods by a seasonally frozen layer.This concept relies on the fact that thawing of the top ground layer frozen during the winter is still not complete by the time of water release from the temporary reservoir (the irrigation basin).There is therefore no need for artificial freezing of such dams.

Thus,classification of dam types according to the thermal state is based on the hydrothermal regime of the water-retaining element during operation of the dam.

It should be noted that no general consensus exists in the normative literature concerning the principles of constructing dams on permafrost.TheGuidelines for Design and Construction of Embankment Dams for Industrial and Domestic Water Supply in Far Northern and Permafrost Regions(Vodgeo Institute,1976) explicitly recommend that the combination of Principles I and II,as well as frozen and unfrozen designs at one dam site,be avoided.The departmental building codeVSN 30-83,Instruction for Design of Hydraulic Structures in Permafrost Regions,developed by the USSR Ministry of Energy (Minenergo SSSR,1983)and the national building codeSNiP 2.06.05-84*,Embankment Dams(Gosstroy USSR,1991) accept the combined use of two construction principles for the water barrier elements of a project.Moreover,where the river is underlain by a deep talik and the flood plain contains a thick layer of thaw-unstable permafrost,VSN 30-83recommends considering a composite design consisting of a concrete structure within the river channel flanked by earth embankments.The concrete section rests on an unfrozen foundation,while the embankment portion should be of the frozen type.It is recommended to use refrigeration systems in transition zones between the concrete section and embankment sections.

The stability of frozen dams (Principle I) relies on the high strength and imperviousness to water of frozen ground.The frozen condition in dams and foundations can be achieved by natural or artificial freezing(Biyanov,1975;Zhang,1983;Biyanovet al.,1989).

Dams with permanent reservoirs require artificial ground freezing.A frozen core can be created by placing the material in lifts for winter freezing,or by means of refrigeration systems operated year round or seasonally.The typical system is constructed of pipes through which a coolant is circulated.Refrigeration systems can be classified as closed or open type,and as passive or active,using natural convection or forced circulation,respectively.They use air,a liquid (e.g.,brines,kerosene),or a two-phase substance (e.g.,ammonia,freon) as the heat transfer media.

Simple techniques from the past century still work well to maintain the frozen state of dams,such as snow removal from the crest and downstream slope,placement of a shelter on the downstream slope to keep snow off the dam surface and to provide cold air ventilation in winter and shade from the sun in summer,and using insulation on the crest and downstream slope.In recent years,new effective insulation and waterproofing materials,as well as albedo-changing techniques such as riprapping the dam crest and slopes with light-colored rocks or painting the surface white,have been used widely in combination with refrigeration systems.

Unfrozen dams designed and constructed using Principle II require measures to protect the toe,crest,and downstream slope from freezing.The advantage of Principle II is that no special requirements are imposed on the layout of a dam relative to appurtenant structures of the development.

VSN 30-83recommends Principle I (frozen dams)for sites where:

·The foundation is composed of ice-rich,thaw-unstable materials (thaw susceptibility class III,thaw strain >0.05);and/or

·The underflow is less than 3×10-5m/s,and the thickness of a talik is less than 15 m.

Principle II (unfrozen dams) is preferable for sites where:

·The foundation consists of rocks or thaw-stable soils (thaw susceptibility class I or II,thaw strain<0.05);and/or

·The stream channel has a deep or open talik,while the valley slopes and flood plain consist of thaw susceptibility class I and II materials.

Thus,embankment dams in permafrost regions operate in a complex thermal stress and hydrodynamic field.Maintaining the quasi-stable condition to provide the stability of the structure as a whole is a difficult engineering challenge.Experience in the permafrost regions with severe climate and complicated subsurface conditions has demonstrated that,quite often,embankment dams undergo a transition in thermal state,from frozen to thawed and from thawed to frozen.

Where seepage through the embankment and foundation is low or nonexistent,the dams freeze from the surface.This was also confirmed by mathematical modelling (Zhang,1983).Among the dams which were naturally frozen during the operation period are the dams constructed in the north of the European part of Russia,Transbaikal,Yakutia,and Magadan Province for water supply and reclamation purposes(Tsvetkova,1960;Biyanovet al.,1989;Zhang,2002).The transition of embankment dams from the unfrozen to the frozen state leads to increased static and seepage stability.However,this process is associated with a number of frost-related problems.For example,freezing of the earth core may result in its cracking,while freezing of the drainage elements will increase the risk of piping due to the rise of the seepage line.The crest and slopes may be subject to frost heave and,upon thawing,to settlement,solifluction,and thermal erosion.Complicated geocryological processes result from freezing in rockfill embankments where the thermal regime is largely determined by convective heat exchange with ambient air.At the Vilyui Hydro-1,2 dam,for example,cooling of the downstream shell was so strong during the first years of dam operation that it resulted in freezing of the talik beneath the Vilyui River,making grouting of the foundation unnecessary.In summer,however,moisture condensation was found to occur in the rockfill,resulting in the formation of an ice-rock mass which impeded convective transfer and led to a reverse process of embankment warming (Kamensky,1977;Olovin and Medvedev,1980).

Processes in frozen dams,which are the most common type constructed in permafrost regions,will be discussed in more detail below.

The major threat to static stability and especially to seepage strength of dams is posed by their rapid transition from the frozen to the thawed state.The rate of this transition may be very high,depending on subsurface conditions.The process proceeds in an unpredictable manner in jointed bedrock with fissures filled with ice,as well as in ice-saturated rocks in zones of tectonic shattering.Ice in fissures melts slowly and seepage is not detected until continuous seepage paths develop.Resulting flow seepage leads to enhanced convective heat transfer between the water flow and surrounding ground and to impetuous growth of the thaw zone.If the project has no monitoring system,permafrost degradation is detected too late,resulting in a sudden,catastrophic increase in the seepage rate,potential failure,and the loss of system function.

These processes have accelerated in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries due to climate change on the planet.Climate change is a fact:warming has occurred and continues to occur(Zubakov,2005).Although some studies demonstrate,based on air temperature frequency-amplitude analysis and observational data,that the rate of warming has recently slowed in northern European Russia,northeastern Canada,and eastern Mongolia,with some areas beginning to show a cooling trend (Pavlov and Malkova,2005).Balobaevet al.(2009) believe that the warming period will end soon and the phase of cooling will come again.Similar situations have repeatedly occurred in Earth’s history.Climate change is driven by the so-called climatic cycles close to solar activity cycles,as well as by the orbital and planetary factors related to the position of the Earth and other planets in the solar system relative to the Sun.There is widespread interest in climate change,since it has impacts on every aspect of human life.Risks associated with resource development are especially high in the vast permafrost zone,which occupies about 65% of Russia and is becoming the epicenter of accelerated economic development.Table 1 is provided to illustrate the magnitude of recent warming in permafrost regions of Russia(Pavlov and Malkova,2005).

Table 1 Regional characteristics of the contemporary climate warming in the Russian permafrost regions

Observed climate warming has altered the thermal regime of the upper permafrost which provides a foundation for infrastructure.It should be noted,however,that structural-stability effects of temperature changes vary with the type of infrastructure.It is common knowledge that engineering properties of frozen soils depend on temperature.For example,an increase in temperature from-4 °C to-1 °C results in a 2.5-fold reduction in adfreeze shear strength of frozen fine-grained and sandy soils (Gosstroy USSR,1990),potentially threatening the integrity of civil and industrial structures.For frozen-core dams,temperature requirements are not so stringent because the hydraulic properties remain virtually unchanged in the said temperature range.The frozen mass will be impermeable to water as long as its ice exists.The presence of ice in the soil pores is certainly dependent on the complex thermodynamic condition in the system.In practice,however,the frozen mass will remain impervious within a wide temperature range,from near 0 °C to lower values.On the other hand,stability problems resulting from faulty design,substandard construction,or poor maintenance should not be attributed to climate warming.

2 Results and discussion

Transition of embankment dams from the frozen to thawed state is examined below using the Myaundzha dam as a case study.The dam is located on the Myaundzha River in the town of the same name in Magadan Province,Russia (63°02′03′′N,147°10′50′′E).It was constructed between 1952 and 1955 to create a cooling water reservoir for the Arkagalinskaya Power Station.It was the first dam of the frozen type in northeastern Russia.

The Myaundzha River flows into a tributary of the Kolyma River at its headwaters.It is fed by snow meltwater in the spring and by rainfall in the autumn.In winter the river freezes to the bottom and has no flow.The mean annual precipitation is about 270 mm,of which 75% occurs during the summer and autumn months.The snow depth is up to 350 mm.The mean annual air temperature is-12.7 °C,with the maximum temperature of +16.6 °C in June and the minimum temperature of-44 °C in January.The record minimum temperature is-55 °C.The dam site is located within the zone of continuous permafrost 180 to 200 m in thickness.The active layer is 0.5 to 3.5 m deep.A talik beneath the river channel extended to a depth of 20 m at the dam site prior to construction.

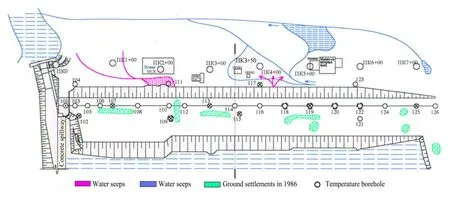

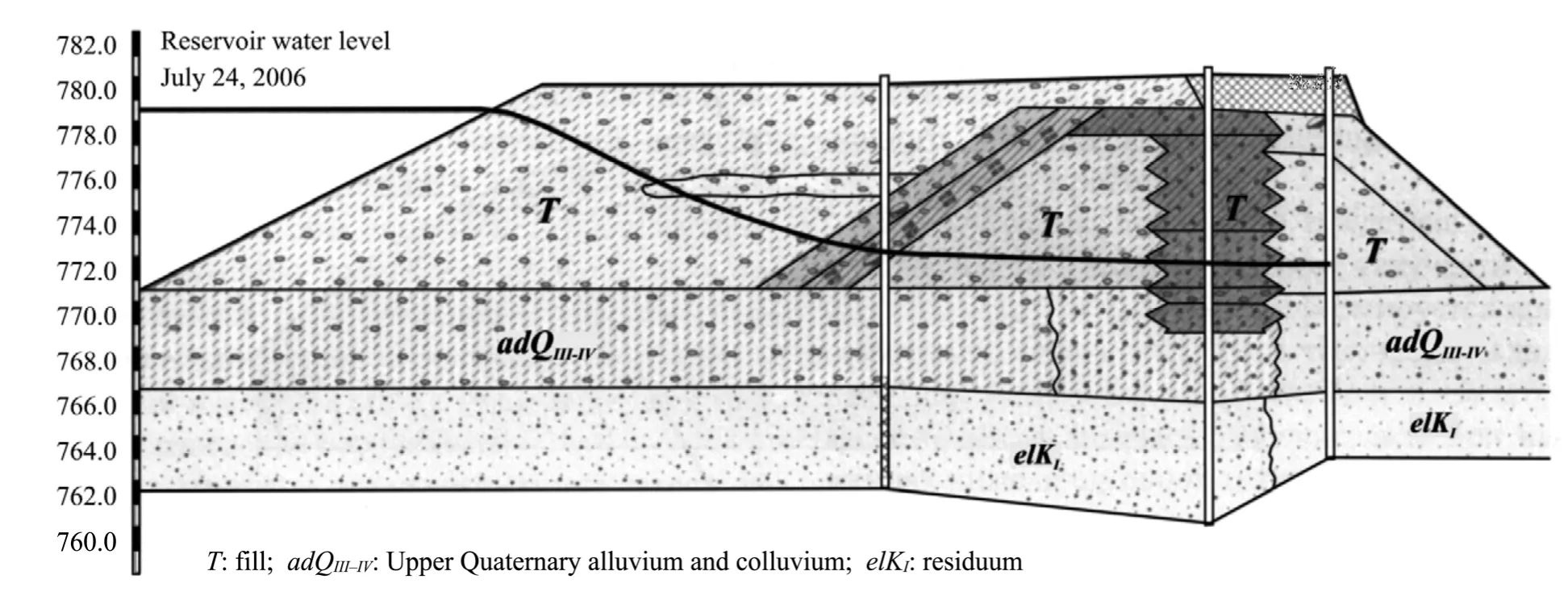

The Myaundzha project consists of a reservoir,a frozen-core earthfill dam,and a spillway consisting of a concrete weir,a discharge channel,and a cantilever bucket.Figure 1 is a general view of the project.Figure 2 shows the location of temperature boreholes,seepage water exits,and embankment subsidence.Figure 3 is a cross section of the dam embankment at Sta.3+50.

The reservoiris used for seasonal storage of water with an active capacity of 4,400,000 m3.The damis an earthfill structure,12.0 m high,870.0 m long at the crest,and 11.5 m wide,constructed with a mixture of cobble,gravel,and sand.The upstream face has a slope of 1:2 and the downstream face is sloped at 1:1.5.

An impervious barrier is provided by a frozen core with a 6-m-wide cutoff of rubbly silt cut into the alluvial foundation materials.A layer of peat protected with riprap was placed on the dam slopes and crest to provide the thermal insulation for the frozen core.The shells were constructed of poorly rounded rock fragments of argillaceous sandstone of varying sizes:20%–60% cobble and coarse gravel,40%–60% fine to medium gravel,and 10%–20% sand with fines.Borrow material for the dam core consisted of 40%–50%rubble and 15%–20% particles finer than 0.25 mm,and had a plasticity index of 8.5 to 9.3.Silty clay for the dam core was excavated in the borrow area by bulldozers in layers as they thawed naturally,and it was placed in a thawed state when the air temperature was above 0 °C.The material in the lower part of the cutoff trench was compacted manually,while the following lifts were compacted with bulldozers and 10-ton rollers.

The bedrock in the dam foundation consists of weathered basalt,andesite,and basaltic andesite.The weathered rocks are heavily fractured and the fractures are filled with ice and fines.The bedrock is overlain by alluvial and colluvial deposits with a thickness of up to 4–5 m,consisting of rubbly sandy silts and clayey silts on the slopes and gravels in the river channel.The flood plain alluvium is covered by a layer of peat and ice-rich sandy silts,reaching a thickness of 1 m.The thaw strain of the alluvium is 10%–15%.Two taliks were encountered,one beneath the main channel and the other below the side braid of the Myaundzha River,extending to a depth of 20 m.The gentle slope in the right abutment area is composed of muck and peat materials of colluvial and soliflual origin which contain numerous ice wedges.The ice wedges form polygons with 15-to 20-m side lengths and penetrate to depths of 5 to 7 m.

The ogee concrete spillway with an overflow length of 200 m is located in bedrock on the left bank of the valley and has a discharge capacity of 338 m3/s.No measures were provided to control seepage in the spillway foundation.

Operation and performance:To create and maintain the frozen core,two different refrigeration systems were used for the Myaundzha dam.Initially,a cold-air refrigeration system was installed to freeze the core of the dam and the riverbed talik using the cold ambient air.The system consisted of 494 vertical pipes embedded 6 to 10 m into the bedrock foundation.The pipes running the length of 330 m along the dam crest were spaced at 1.5 m in the riverbed section and 2 m apart in the remaining part.Each pipe,100 mm in diameter and 16 to 24 m in length,had an inner 57-mm-diameter pipe located concentrically inside it.The inner pipes were connected to a metal duct,from which the air was forced out by blowers with a delivery rate of 10,000 m3/h.The air flow rate through one pipe was 200 m3/h.One fan serviced 50 pipes.Forced air movement through the inner pipe drew in cold ambient air into the outer pipe,increasing the efficiency of heat removal from the unfrozen ground.Using the cold-air refrigeration system,the talik beneath the river bed was refrozen over the period of 1953 to 1954 (Tsvetkova,1960).

Figure 1 Myaundzha Dam,a general view along the crest (Photo by S.A.Guliy,2002)

Figure 2 Location of temperature and piezometric boreholes,and seepage water exits at the Myaundzha Dam

By the winter of 1954–1955,the dam was 7.2 m high,but further construction was halted due to seepage detected beneath the concrete spillway in August of the same year,after the reservoir had filled to 3 m.The cause of the seepage was that no grout or frozen barrier was incorporated in the spillway design.This element of the project was designed and constructed following Principle II described above.

From May 1955 to May 1957,the talik expanded 45 m downwards and 90–95 m towards the dam.This process was accompanied by increasing seepage rates,thus calling for special measures to mitigate the problem.A sump and a pumping station were constructed to return all seepages back into the reservoir.Up to 7,000 m3/h of water was pumped daily.Because continued thawing presented a serious threat to the structural integrity of the dam,several rehabilitation measures were undertaken,including grouting of the thawed zones in the foundation,enhancement of the refrigeration system,placement of a 0.3–0.5 m clayey silt apron in front of the spillway,and addition of riprap on the downstream slope.In late August 1957,the cold-air refrigeration system operating only in winter was replaced by a brine refrigerant system operated year-round.The liquid system was installed at 1.5-m spacing 2 m away from the cold-air pipes.

In the end of 1959,the dam was in immediate danger of failing because of brine leakage from the refrigeration system and piping of the saline core material,resulting in the development of voids and sinkholes.The problem was resolved only in 1960–1962 by grouting the fractured bedrock below the spillway and the dam to a depth of 40 m from the crest (Vedernikov,1963).As a result,the seepage was reduced tenfold and this allowed re-creating in 1962 a frozen barrier in the dam core and down to 20 m in the foundation where there was no seepage.This was the situation with the Myaundzha dam in the late 1960s to the early 1970s.

Conclusions drawn then were as follows.The fundamental error was the adoption of two design concepts for the water-barrier elements.The concrete spillway was constructed without any seepage control features and without preserving the permafrost in its foundation to provide an impervious barrier,while the earthfill dam was designed and constructed to maintain the dam core and foundation in a frozen state.As a result,progressive thawing of the fractured bedrock beneath the spillway began to impose a warming effect on the frozen embankment core,requiring extensive and costly remedial measures to arrest the problem.However,even after 20 years of operation the thermal regime of the dam was not adequately restored.The design flaw was that the cutoff of the dam was not deep enough to penetrate through the weak alluvial deposits into the bedrock.

Rehabilitation works continued over the following years.In 1974–1977,the upstream shell of the dam was widened 15–34 m towards the reservoir,while the crest was raised an additional 1–2 m to reduce seepage losses and improve the thermal regime of the dam.Experience showed that the frozen impervious core should be 3 m thick to perform reliably.However,many years of efforts to restore the adequate performance of the frozen core failed,and in 1998 the refrigeration system was shut down.Since then,the dam has been operated as an unfrozen dam according to Principle II.

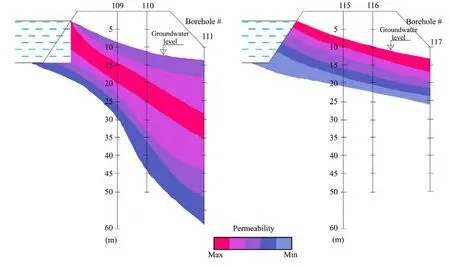

Investigations and inspections conducted by the Melnikov Permafrost Institute’s research station in Magadan in the late 1990s to the early 2000s found that the dam was in a satisfactory condition and properly performed its function of providing water for the power station.The thermal regime of the dam,however,had undergone significant changes.As a result of the long-term operation,the dam had changed its state from frozen to thawed (Guliy,2011).Formal conversion of the dam to the thawed operation concept is presently under consideration.Figure 4 shows the variation in 0 °C isotherm along the longitudinal axis of the dam for the period from 1999 to 2010.Figure 5 shows the seepage zones in the dam embankment and foundation at Sta.2+00 and Sta.6+00 as of 2002 with the account of data obtained in 1988.

Figure 3 Geological cross section,Sta.3+50,Myaundzha Dam

Figure 4 0 °C isotherms between 1999 and 2010 along the axis of Myaundzha Dam

Figure 5 Seepage zones in the Myaundzha dam embankment and foundation,Sta.2+00 and Sta.6+00,in 2002

3 Conclusion

Experience with the Myaundzha dam has provided an important scientific and practical realization that dams operating in the severe climatic and complicated permafrost conditions of eastern Siberia can transition from frozen to thawed states while still maintaining their seepage strength and structural stability.A further fundamental task is to elaborate dam construction principles for permafrost regions,which should be clearly stated in building norms and regulations.

Balobaev VT,Skachkov YB,Shender NI,2009.Predicted changes in climate and permafrost thickness for central Yakutia to the year 2200.Geografia i Prirodnye Resursy,2:50–56.

Biyanov GF,1975.Dams on Permafrost.Energiya,Moscow.

Biyanov GF,Kogodovsky OA,Makarov VI,1989.Embankment Dams on Permafrost.Permafrost Institute Press,Yakutsk.

Gosstroy USSR,1990.Building Code SNiP 2.02.04-88,Foundations in Permafrost.Gosstroy,Moscow.

Gosstroy USSR,1991.Building Code SNiP 2.06.05-84*,Embankment Dams.Gosstroy,Moscow.

Guliy SA,2011.Performance of an embankment dam after transition from a frozen to thawed type:The Arkagalinskaya hydroelectric dam on Myaundzha River.In:Zhang RV (ed.).Permafrost Engineering,Proceedings of the IX International Symposium.Melnikov Permafrost Institute SB RAS Press,Yakutsk,pp.238–242.

Kamensky RM,1977.Thermal Regime of the Dam and Water Reservoir,Vilyuisk Hydro.Permafrost Institute Press,Yakutsk.

Melnikov Permafrost Institute,2012.Small Dams on Permafrost in Yakutia:Guidelines for Design and Construction.Melnikov Permafrost Institute Press,Yakutsk.

Minenergo SSSR,1983.VSN 30-83,Instruction for Design of Hydraulic Structures in Permafrost Regions.Minenergo SSSR,Leningrad.

Olovin BA,Medvedev BA,1980.Temperature Field Dynamics in the Viluy Hydro Dam.Nauka,Novosibirsk.

Pavlov AV,Malkova GV,2005.Current Climate Changes in Northern Russia.Geo,Novosibirsk.

Tsvetkova SG,1960.Experience with dam construction in permafrost areas.In:Bondarev PD,Porkhaev GV,Tsvetkova SG(eds.).Materials to Fundamentals of Frozen Crust Studies,Vol.VI.USSR AS Press,Moscow,pp.87–110.

Vedernikov LE,1963.Geocryological processes in the body and foundation of the dam on the Myaundzha River.Transactions of VNII-1,22:179–239.

Vodgeo Institute,1976.Guidelines for Design and Construction of Embankment Dams for Industrial and Domestic Water Supply in Far Northern and Permafrost Regions.Stroyizdat,Moscow.

Zhang RV,1983.Prediction of Temperature Regime of Small and Medium Embankment Dams in Yakutia,Interim Guide.Permafrost Institute Press,Yakutsk.

Zhang RV,2000.Design,Construction,Operation and Maintenance of Small Dams in Permafrost Areas (on the Example of Yakutia).Melnikov Permafrost Institute SB RAS Press,Yakutsk.

Zhang RV,2002.Temperature Regime and Stability of Small Dams and Earthen Canals on Permafrost.Melnikov Permafrost Institute SB RAS Press,Yakutsk.

Zubakov VA (ed.),2005.Proceedings of Russian Conference,Climate Change in the XXI Century:Current Trends,Predicted Scenarios and Estimated Consequences.INENKO,St.Petersburg,UAS.

Sciences in Cold and Arid Regions2014年4期

Sciences in Cold and Arid Regions2014年4期

- Sciences in Cold and Arid Regions的其它文章

- Thermal conductivity of reinforced soils:A literature review

- In-situ testing study on convection and temperature characteristics of a new crushed-rock slope embankment design in a permafrost region

- Advances in studies on concrete durability and countermeasures against freezing-thawing effects

- Cooling effect of convection-intensifying composite embankment with air doors on permafrost

- Case studies:Frozen ground design and construction in Kotzebue,Alaska

- Thermal state of ice-rich soils on the Tommot-Yakutsk Railroad right-of-way