Methane hydrate formation comparisons in media with and without a water source supply

Peng Zhang ,QingBai Wu

State Key Laboratory of Frozen Soil Engineering,Cold and Arid Regions Environmental and Engineering Research Institute,Chinese Academy of Sciences,Lanzhou,Gansu 730000,China

1 Introduction

Natural gas hydrates are solid,non-stoichiometric compounds of small gas molecules and water (Sloan,2003).Many geological surveys have verified that natural gas hydrates are commonly formed in the sediments on continental slope and permafrost around the world,existing under appropriate temperature and pressure conditions.In that the main gas component in natural gas hydrate is methane (Kvenvolden and Rogers,2005) and the organic carbon amount stored in this reservoir has been estimated as about twice of that in other conventional oil and gas resources (Mac,1990;Kvenvolden,1995;Max and Lowrie,1996),the gas hydrate reservoir in nature has been recognized as a potential future energy resource.It is also important to note,however,that the dissociation of natural gas hydrate releases methane (a greenhouse gas) into the atmosphere,which causes global warming(Kvenvolden,1998).

In nature,most natural gas hydrates exist in the sediment,and only about 6% in the bulk form.Additionally,the constituents of natural sediments are quite complex,including mineral particles,organic debris,fossil remainsetc.,and each element of the sediment lithology can affect the occurrence properties of gas hydrate (Collettet al.,1988;Uchida and Tsuji,2004;Uchidaet al.,2004a).Many researchers have done extensive work describing the aspects (Buffett and Zatsepina,2000;Klauda and Sandler,2001;Wilderet al.,2001;Ostergaard,2002;Uchidaet al.,2002;Andersonet al.,2003a,b;Klauda and Sandler,2003).Since there is a large particle area and a large number of capillaries in the fine-grain sediments,the physical and chemical properties of the water confined in the micro-pore sediments are clearly affected by sediment lithology (Hillset al.,1996;Findeneget al.,2008;Ricciet al.,2009).Some researchers (Chuvilinet al.,1999;Kawasakiet al.,2005) have done work on the water change characteristics during the gas hydrate formations in sediments,and have indicated that there was water transfer behavior during the reactions.So far,most researchers have been paying close attention to the effects of the sediment lithology on hydrate formation,but few researchers have done any work to connect water contents with hydrate formation characteristics.

Handa and Stupin studied the thermodynamic properties and dissociation characteristics of gas hydrates in 70-Å-radius silica-gel pores (Handa and Stupin,1992).Subsequently,Clennellet al.(1999),Uchidaet al.(199,2002,2004b),Ostergaardet al.(2002) and Andersonet al.(2003a,b) and many other researchers completed extensive work on the effects of different kinds of porous media on the gas hydrates pressure/temperature conditions.They all indicated that the media characteristics could considerably affect the pressure/temperature conditions of hydrate formations;however,none of the researches explored the water content changes of media and the hydrate formation characteristics following pressure/temperature changes.

In the natural media,some physical properties of natural gas hydrate are similar to those of ice inside media (Sloan,1998a;Henryet al.,1999).Gas hydrates formation and dissociation processes resemble the processes of the freezing and thawing of ice (Henryet al.,1999),with similar water transfer behaviors during the two kinds of processes.Some researchers also indicated that gas hydrate aggregation could be compared to ice-lens in fine-grain sediments (Macet al.,1994) and the "freeze-dry" phenomenon may be observed in coarse-grain sediments during hydrate formation (Pearson,1981;Pearsonet al.,1983).

Using an observation system,Tohidiet al.found the CH4and CO2gas hydrate formations in liquid tetrahydrofuran former.They revealed that clathrates were formed within the center of pore spaces,and cementation of grains only occurred where a large proportion of pore space was filled with hydrate(Tohidiet al.,2001).Chuvilinet al.(1999) examined the water transfer behavior of gas hydrate formation processes in porous media.They studied the residual nonclathrated water in sediments in equilibrium with gas hydrate and indicated that there was nonclathrated water by analogy to unfrozen water in the media,and it could influence the mechanical properties of hydrate-containing sediments (Chuvilinet al.,2011).Kneafseyet al.(2007) studied the water transfer during the hydrate formation process with CT technology.However,all the above studies do not combine water transfer,nonclathrated water and formation spaces with gas hydrate formations in media to explore their formation characteristics and processes.

In nature,the configurations of the gas hydrates inside media present four different forms:disseminated,nodular,layered and massive (Sloan,1998b),which are similar to those of ice in the permafrost science.In permafrost,the different ice configuration formations were ascribed to the water transfer behaviors caused by temperature differences.Therefore,the differences of the configurations (Sloan,1998b) of the gas hydrates should have some foreseeable relations with the water transfer behaviors in media.Hence,this research is aimed at analyzing water transfer behaviors in gas hydrate media,with the goal of discovering the real reasons behind differing gas hydrate configurations.

2 Experimental section

2.1 Experimental media

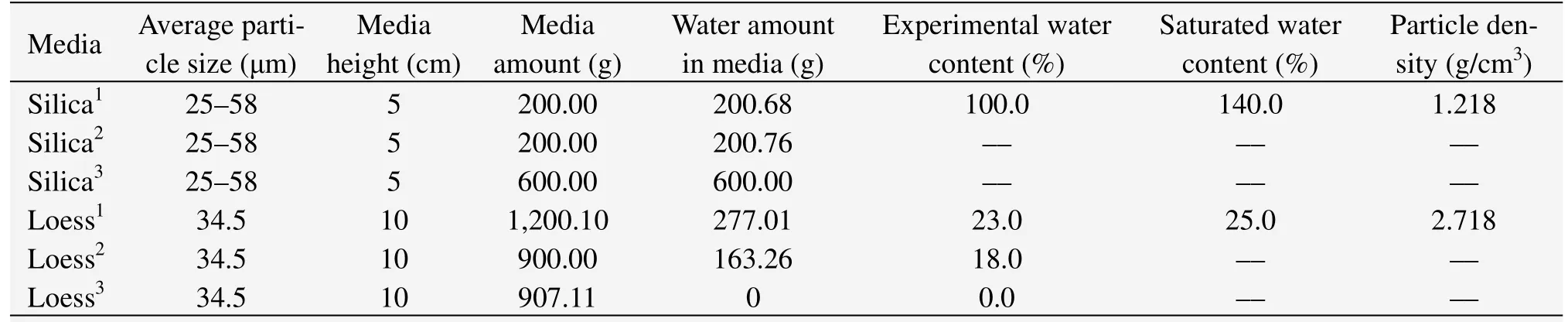

In this study,the experimental procedures were conducted with an experimental apparatus we designed and assembled ourselves (Zhanget al.,2009).Using this device,we studied water transfer characteristics inside sediments during methane hydrate formation (Zhanget al.,2010).Silica gel powders,which have been used by many researchers(Shangbang Industrial Co.,Ltd.in Shanghai,China)and a natural medium-loess (taken at 1.5 meters underground in Yuzhong County in Lanzhou,China)were chosen as the experimental media.There are a large number of capillaries in loess,so it has a strong water-holding capacity and can act as an excellent water reservoir.For these reasons,loess was also chosen as the experimental medium.The physical properties and the experimental conditions of the media were listed in table 1.

Experimental media were assembled with silica gel powder and loess in a double-layered configuration.The silica gel powder acted as the superstratum in which methane hydrate was formed,and the loess acted as the underlayer,which was the only water source.In these experiments,tests of different water sources containing variable water contents were carried out by changing the water contents of loess,of which the water contents were predesigned as 23%,18% and 0% (number as 1,2,3).The water contents were adjusted with distilled water,and those designated as 0% were completely dry.The water content of silica gel powder layers were all kept at a constant 100%.

Table 1 Physical properties of the experimental media

2.2 Experimental method

In this study,methane hydrate was formed solely in the superstratum silica gel powder layer of the double-layer media.The loess underlayer functioned only to supply liquid water to the superstratum without any hydrate formation.Therefore,the water migration during hydrate formation processes and the resulting reaction characteristics may be comprehensively studied.

As shown in table 1,each height of the three double-layer experimental samples was 15 cm,where the height of the superstratum silica gel powder layer was 5 cm and that of the underlayer loess layer was 10 cm.In each experimental medium,three water-detecting sensors from the Germanic GEO-Precision Environment Technology Company were buried in the middle of each of the two layers,to detect water content changes.The depth of the three sensors was about 2.5 cm,7.5 cm,12.5 cm,respectively.

To ensure that the methane hydrate was formed only in the 5 cm silica powder layer in each experiment,the formation conditions of the hydrate in the different media needed to be defined.Consequently,under the initial 8.5 MPa gas pressure and 12 °C temperature conditions,methane hydrate was firstly formed in a pure silica gel power medium with 100%water content and two pure loess media with 23%,18% water contents.According to the experimental results,the experimental conditions of the hydrate formation in double-layer media were defined as following:an initial experimental condition of 8.5 MPa gas pressure and 12 °C temperature,and an ending condition of 8 °C temperature.

At the beginning of the experiments,the experimental system was evacuated for approximately five minutes;then,the methane gas at 99.99% purity from Hongzhuo Chemical Co.,Ltd in Chengdu of China was released into the reaction cell until the pressure reached the predesigned value.The reaction cell was a stainless steel cylinder (height 19.5 cm,diameter 10.0 cm,volume 1,434.81 cm3) and could be used in 0–20 MPa and-50 to 100 °C ranges.Following that,using a low-temperature bath (-10 to 80±0.05 °C and made by the JULABO Labortechnik GMBH),the reaction system was cooled from 12 °C to 8 °C in 80 minutes.Hence,the methane hydrate could be formed only in the silica gel power layer.Subsequently,the temperature remained at 8 °C for an extended period of time for sufficient hydrate formation.During the reaction processes,gas pressure,temperature and water content parameters were all logged and saved by two computers.

3 Results and analysis

3.1 Hydrate formation reactions

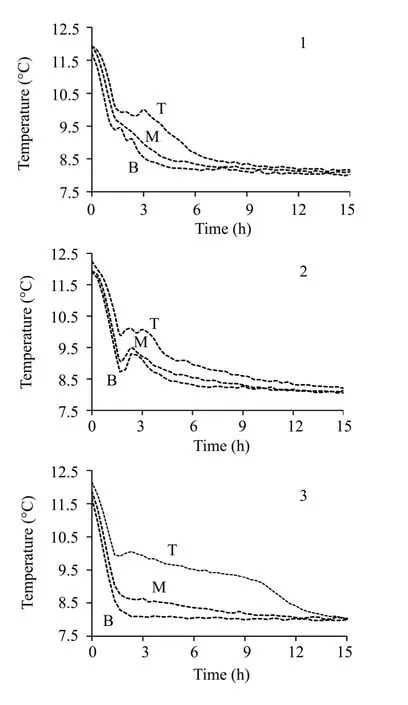

Methane hydrate formation experiments were conducted in three kinds of double-layer experimental media:10 cm loess underlayers with different 23%,18%,and 0% water contents,each with the same 5 cm silica gel powder superstratums with 100% water content.As shown in figure 1,the three types of media were numbered as 1,2,and 3,respectively.Through cooling,the methane hydrate was formed in the superstratum silica gel layer of the double-layer structure.As shown in figure 1,while the temperature of silica gel layer was respectively decreased to 10.1 °C in the medium 1,9.9 °C in the medium 2,and 10.0 °C in the medium 3,the temperature clearly rose afterward,indicating that the hydrate began nucleating and releasing considerable amount of heat.The gas pressure in figure 2 was 8.45 MPa,8.50 MPa,and 8.44 MPa at that time,respectively.In addition,as shown in figure 1,after the heat was released from the formation reactions,it diffused into the underlying middle and bottom layers from the top layer and caused the temperature increase of the two layers.

In each formation experiment,the hydration coefficientm(CH4•mH2O) kept constant.Therefore,using the depletion amounts of liquid water converted into hydrate in a medium,the reaction ratios of the formation reactions can be computed.The conversion ratio changes during the experiments are listed in figure 3,indicating that the water conversion ratios continued rising as the reaction times proceeded,which indicates that more and more liquid water inside media was converted into hydrate.The final water conversion ratios were different in the three experiments,coming out as 44.75%,70.96% and 77.33%.Additionally,the shape features of the curves in figure 3 are also different,indicating that the reaction characteristics in the three experiments presented visible differences and that the reactions were clearly affected by the water sources.The gas pressure changes in figure 2 also showed the differences.

Figure 1 Temperature decreasing processes during the reactions (1,2,3 respectively signifies the reaction in the underlayer loess layer with 23%,18%,0% water content.T,M,B respectively denotes the top,middle,bottom part of one experimental medium)

3.2 Water transfer during hydrate formation reactions

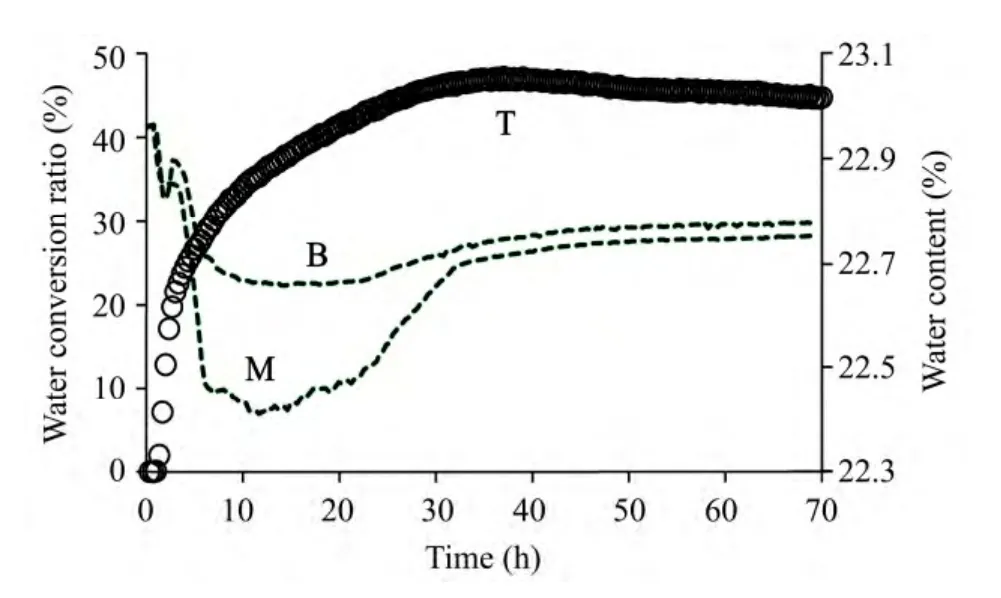

While gas hydrates are being formed,liquid water will converge into the hydrate surface with lower Gibbs free energy (Sloan,1998c).Therefore,the water transfer behaviors will emerge following hydrate formation in media.In order to explore the water absorption behavior water and the formation reaction characteristics of hydrate in media,we designed a double-layer media,in which the methane hydrate was formed only in the superstratum,and the underlayer served as the only supply of liquid water for the reaction.Utilization of the water source by hydrate during reactions is shown in figures 4 and 5.Comparing the two figures,it is found that the water reserved in the two water sources was both utilized,indicating that while gas hydrate was being formed,a kind of suction force was created that absorbed the necessary liquid water for the hydrate formation.As shown in figures 4 and 5,following the reactions,the water contents of the water sources were decreased by different degrees.After formation reactions,the water content of the reservoir with 23% water content was decreased to 22.75%.However,the water content decrease in the reservoir with 18% water content presented various in the vertical direction:it changed to 18.38% on the middle part,exhibiting the water content rising phenomenon;and the water content of the bottom reservoir changed to 16.81%.These experimental results show that water utilization by hydrate formation occurred differently in different water reservoirs,indicating that the amount of liquid water present can affect the hydrate formation reactions.

Figure 2 Gas pressure dropping processes during the reactions (1,2,3 respectively signifies the reaction in the underlayer loess layer with 23%,18%,0% water content)

Figure 3 Water conversion change processes during the reactions (1,2,3 respectively signifies the reaction in the underlayer loess layer with 23%,18%,0% water content)

3.3 Section characteristics of formation react ions

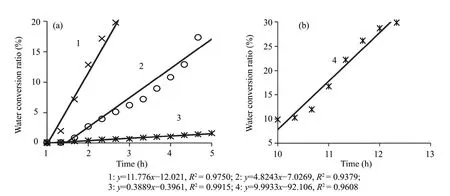

Comparing the three curves in figure 3,one finds that the characteristics of change of the water conversion ratios versus time indicate distinct section properties.As shown in figure 6,the curve 1 can be divided into two sections:one linear section and one quadratic curve section;the curve 2 is an integral quadratic equation curve;the curve 3 can be divided into three sections:two linear sections and one quadratic curve section.These results indicated that there were clear differences in the hydrate formation reactions with different water allocations.The formation reaction supplied by the water source with 23% water content first went through a process in which the water conversion ratio changed,and then proceeded through a separate process where the ratio remained.The formation reaction supplied by the water source with 18% water content progressed through a ratio changing process.The formation reaction supplied by no water source went through constant ratio,ratio changing,and constant ratio processes,in that order.The results show that the water sources which can be utilized by the formation reactions can affect the growth processes and the reaction ratios of the hydrate formation.

Figure 4 Water content changes following reaction time on different parts in the double-layer medium with 23% water content of underlayer (T:top part;M:middle part;B:bottom part)

Figure 5 Water content changes following reaction time on different parts in the double-layer medium with 18% water content of underlayer (T:top part;M:middle part;B:bottom part)

4 Discussion

4.1 Effects of water sources on hydrate nucleation

According to the above analysis,it is found that while gas hydrate is being formed,a kind of suction force will be produced through which the hydrate will absorb the necessary liquid water for its formation.The intrinsic reason for this is that the liquid water will converge into the hydrate surface with lower Gibbs free energy (Sloan,1998c).Therefore,the whole formation processes of hydrate,from nucleation to growth,will be affected by the water source which can be utilized by the formation reaction.

In the nucleation period,the water source under the hydrate formation part can affect the nucleation reaction through its thermal property differences.Combining the figures 1 and 3,the nucleation periods of the hydrate were defined and the corresponding periods in figure 3 were intercepted and shown as figure 7.As shown in the figure 7a,the nucleation ratio of hydrate with No.1 water source is more 2 times the nucleation ratio with No.2 water source and more 30 times the nucleation ratio with No.3 water source.Taking the thermal properties of the water source in table 2 into account,it is found that the water sources have heat conducting capabilities.The formation reaction of hydrate is a heat releasing reaction.Hence,if the heat released from the hydrate formation reaction is rapidly diffused,the nucleation ratio will be improved significantly.During the intercepted reaction time 1–5 h in figure 7a,the temperature of the silica gel layer corresponding to curve 1 decreased by 0.86 °C,the temperature of curve 2 decreased by 0.83 °C and the temperature of curve 3 decreased by 0.31 °C.Combining figures 1 and 3,it is found that the formation conditions of the hydrate were generally similar:10.1 °C and 8.45 MPa in medium 1;9.9 °C and 8.50 MPa in medium 2;10.0 °C and 8.44 MPa in medium 3.The facts above show that the water sources with different water contents can only affect the nucleation ratios with their different thermal transmitting capacities,with almost no effect on the nucleation conditions of the hydrate.Analyzing the curve 3 in figure 3,we found there was also a period,10–13 h,in which the water conversion ratios were rapidly rising.Taking the temperature changes in 3 of figure 1 into account,we found that there was also a period of rapid temperature decrease in medium 3 where the temperature of the silica gel powder decreased 0.86 °C in 3 hours.In this period,the reaction ratio in B of figure 7b was close to that in the curve 1 in figure 7a.This fact also proves the effects of heat diffusion on the hydrate formation reaction ratios.

Figure 6 Change characteristics of water conversion in different sections of the reaction processes (1,2,3 respectively signifies the reaction in the underlayer loess layer with 23%,18%,0% water content)

Figure 7 Water conversion change processes during different nucleation sections in different hydrate formation reactions

Table 2 Thermal properties of loess with different water contents

4.2 Effects of water sources on hydrate growth processes

The experimental results indicated that the growth processes of hydrate could be also affected by the water sources.Comparing the figures 4 with 5,one finds that while water sources were different,the water source utilization by hydrate growth was also different.The underlayer loess with 18% water content is unsaturated (Table 1).While hydrate was formed inside the upper silica gel powder layer,the hydrate formation would generate suction of liquid water.After some water in silica gel layer was depleted,the suction force to liquid water would be transmitted down to the loess layer,depending on numerous capillaries.Accordingly,in the 18% unsaturated loess,the suction force was rapidly transmitted down to bottom of the loess layer and some water was pumped out from the bottom,and water slowly replenished the water depleted in the middle of loess.Therefore,as shown in figure 5,the amount of water lost on the bottom part was more than that in the middle.For the water source with an underlayer with 23% water content,the loess is approximately saturated (Table 1)and can supply enough free liquid water to hydrate.Hence,the suction force was not needed to transmit down but directly pumped the free water from the middle of the loess to the surface of hydrate.Thus,the amount of the lost water in the middle of loess was more than that on the bottom,as shown in figure 5.

4.3 Utilization to liquid water during hydrate growth processes

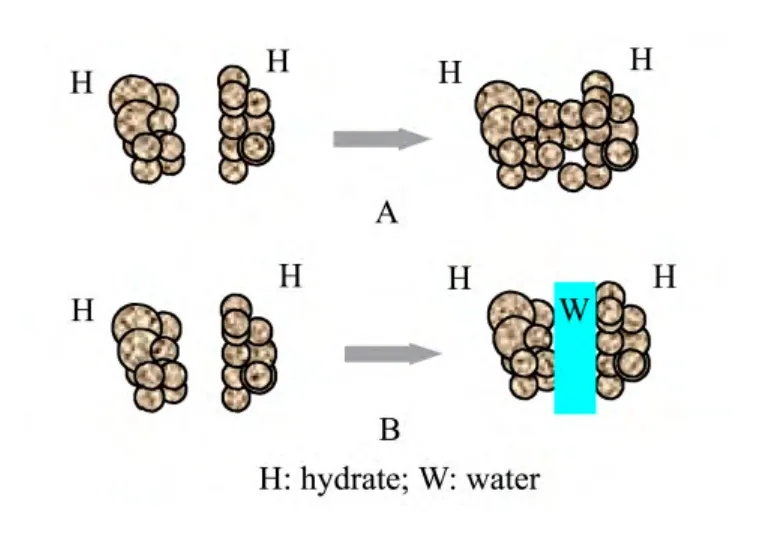

In this study,experimental results have proved that during hydrate formation processes,the hydrate will absorb and utilize some liquid water.However,comparing figures 4 with 5,one finds that there are clear differences in the growth processes of hydrates that depend on the variable water amounts used in the hydrate formation reactions.The water contents in loess in figure 4 went through a first increasing then decreasing process,which indicated that at the beginning of hydrate formation,much water was needed and then some liquid water was discharged.The reason for this phenomenon is that many nucleuses can be generated at the beginning of the hydrate formation reactions while at the same time sizable specific surface areas of nucleation were produced,so much water will converge into the hydrate surfaces with lower Gibbs free energy (Sloan,1998c).Following the progress of the reaction,the hydrate grains will cement together to decrease their specific surface areas as shown in figure 8.As a result,the liquid water absorbed previously by the hydrate formation reaction is now abundant,with some water discharged from the cemented grains.Hence,the phenomenon in figure 4 appeared.However,the water content increase in curve M in figure 5 was caused by the water supply on the bottom of loess rather than in the middle.

Additionally,the curve shapes in figure 3 also showed the effects of the water sources on growth processes of hydrate.Comparing the curves in figure 3,it is found that there is an obvious inflection point C in curve 3,while the inflection points A and B in curves 1 and 2 are less distinct.The reasons for the above observation are that hydrate grains go through a cementation period to decrease the substantial specific surface areas of the grains while the reaction progresses a certain stage.If the cementation only depended on hydrate grains as shown in A of figure 8,which were generated without a water source supply,the cementation process would proceed faster,which is why the visible inflection point C in the curve 3 in figure 3 appeared.By contrast,while there was liquid water present in the cementation processes,the cementation process itself would progress relatively slower,and so the inflection points A and B in figure 3 were less evident.Due to the cementation process,the curves in figure 6 indicating the formation processes of the hydrate also exhibit several sections.The formation reaction generated in the medium No.2 has a substantial water source supply,so it presents a consistent quadratic equation characteristic,as shown in figure 6.The formation reaction in the medium No.3 has no water source supply,so the formation reaction exhibits two linear sections and one quadratic equation section.Finally,the formation reaction in the medium No.1 has an abundant water source supply,so a water discharging stage appeared in the formation process,and consequently the formation reaction exhibits one linear section and one quadratic equation section.

4.4 Effects of water sources on gas amounts

Curve changes in figure 2 show that gas pressure changes during different reactions with different water sources were variable,indicating that the amounts of the methane gas utilized by hydrate formation reactions would also be different.Therefore,using the Clapyron equation,the amounts of methane gas were calculated and the results present the hydration coefficientm(CH4•mH2O) in different media:CH4•7.47H2O in medium 1;CH4• 7.96H2O in medium 2;CH4• 17.13H2O in medium 3.Taking the calculation results into account,it is found that gas contents contained in the hydrate formed with water source supplies were more than that which was formed without a water source.Since methane gas must be dissolved into water and reach a supersaturated state before hydrate was formed,the solubility of methane gas in the initial water near hydrate grains is very high.So,while the fresh water,where the solubility of the methane gas is much lower,migrates to the vicinity of hydrate grains,the hydrate grains formed first will become unstable and some grains will dissociate.While the dissociating capabilities of the fresh water are weakened,hydrate grains will be formed next.Thus,after a few formation processes,the gas amounts contained in the hydrate will be clearly enhanced.

Figure 8 Schematic diagram of growth process of hydrate.A:growth depending on cementation of grains;B:growth depending on absorbing liquid water

5 Conclusions

In this study,two water sources supplying some amount of liquid water used in methane hydrate formation were designed and assembled.Using the different water sources,the whole formation processes of methane hydrate was studied.Experimental results show that both nucleation and growth processes could be affected by the water sources.As nucleation of methane hydrate is a heat releasing reaction,heat transmission can distinctly affect nucleation ratios.The stronger the heat transmitting capability of water source is,the higher the nucleation ratio.While hydrate is formed,a kind of suction force will be created because water will converge into hydrate surfaces with lower Gibbs free energy (Sloan,1998c).Hence,some water will be pumped to the vicinity of hydrate during the hydrate formation processes.Fresh water pumped by hydrate formation can reduce the cementation strength of the hydrate grains and cause the dissociation of some hydrate grains.Further,the hydrate formation reaction processes with different water sources present linear or quadratic equation characteristics.After a few repeated dissociation and formation processes of some fraction of the hydrate grains,gas amounts contained in hydrate formed with the water sources will be noticably enhanced.According to this study,we can conclude that in nature,the differences of gas amounts contained in solid hydrate with different configurations should have some relations with water transfer behaviors in media.

We are grateful for the financial support from the Youth Science Foundation (Grant No.41101070) and the CAS West Action Plan (Grant No.KZCX2-XB3-03).

Anderson R,Llamedo M,Tohidi B,et al.,2003a.Characteristics of clathrate hydrate equilibria in mesopores and interpretation of experimental data.Journal of Physical Chemistry B,107:3500–3506.

Anderson R,Llamedo M,Tohidi B,et al.,2003b.Experimental measurement of methane and carbon dioxide clathrate hydrate equilibria in mesoporous silica.Journal of Physical Chemistry B,107:3507–3514.

Buffett BA,Zatsepina OY,2000.Formation of gas hydrate from dissolved gas in natural porous medium.Marine Geology,164:69–77.

Chuvilin EM,Istomin VA,Safonov SS,2011.Residual nonclathrated water in sediments in equilibrium with gas hydrate comparison with unfrozen water.Cold Regions Science and Technology,68:68–73.

Chuvilin EM,Yakushev VS,Perlova EV,1999.Experimental study of gas hydrate formation in porous media.Advances in Cold-Region Thermal Engineering and Sciences,533:431–440.

Clennell MB,Hovland M,Booth JS,et al.,1999.Formation of natural gas hydrates in marine sediments 1,Conceptual model of gas hydrate growth conditioned by host sediment properties.J.Geophys.,104:22985–23003.

Collett TS,Bird KJ,Kvenvolden KA,et al.,1988.Geologic Interrelations Relative to Gas Hydrates within the North Slope of Alaska.USGS Open File Report,19.76:88–389.

Findeneg GH,Jahnert S,Akcakayiran D,et al.,2008.Freezing and melting of water confined in silica nanopores.Chem.Phys.Chem.,9:2651–2659.

Handa YP,Stupin D,1992.Thermodynamic properties and dissociation characteristics of methane and propane hydrates in 70-Å-radius silica-gel pores.Journal of Physical Chemistry B,96:8599–8603.

Henry P,Thomas M,Clennell MB,1999.Formation of natural gas hydrates in marine sediments 2.Thermodynamic calculation of stability conditions in porous sediments.Journal Geophysical Research,104:23005–23022.

Hills BP,Manning CE,Ridge Y,et al.,1996.NMR water relaxation,water activity and bacterial survival in porous media.Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture,71:185–194.

Kawasaki T,Tsuchiya Y,Nakamizu M,2005.Observation of Methane Hydrate Dissociation Behavior in Methane Hydrate Bearing Sediments by X-ray CT Scanner.Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Gas Hydrates,Trondheim,Norway,June 12–16.

Klauda JB,Sandler SI,2001.Modeling gas hydrate phase equilibria in laboratory and natural porous medium.Ind.Eng.Chem.Re.,40:4197–4208.

Klauda JB,Sandler SI,2003.Predictions of gas hydrate phase equilibria and amounts in natural sediment porous medium.Marine and Petroleum Geology,20:459–470.

Kneafsey TJ,Tomutsa L,Moridis GJ,et al.,2007.Methane hydrate formation and dissociation in a partially saturated core-scale sand sample.Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering,56:108–126.

Kvenvolden KA,1995.A review of geochemistry of methane in nature gas hydrates.Organic Geochemistry,23:997–1008.

Kvenvolden KA,1998.Methane hydrate—a major reservoir of carbon in the shallow geosphere.Chem.Geol.,71:41–51.

Kvenvolden KA,Rogers BW,2005.Gaia’s breath—global methane exhalations.Mar.Pet.Geol.,22:579–590.

Mac Donald GJ,1990.The future of methane as an energy resource.Annual Review of Energy,15:53–83.

Mac Donald IR,Guninasso NL,Sassen R,et al.,1994.Gas hydrate that breaches the sea floor on the continental slope of the Gulf of Mexico.Geology,22:699–702.

Max MO,Lowrie A,1996.Oceanic methane hydrate:A frontier gas resource.J.Petroleun Geology,19:41–56.

Ostergaard KK,Anderson R,Llamedo M,et al.,2002.Hydrate phase equilibria in porous media:effect of pore size and salinity.Terra Nova,14:307–312.

Pearson C,1981.Physical properties of natural gas hydrate deposits inferred by analogy with permafrost.Eos Trans,AGU,62:953–961.

Pearson CF,Halleck PL,McGuire PL,et al.,1983.Natural gas hydrates:A review of in situ properties.Journal of Physical Chemistry,87:4180–4185.

Ricci MA,Bruni F,Giuliani A,2009."Similarities" between confined and super-cooled water.Faraday Discussions,141:347–358.

Sloan ED,1998a.Clathrate Hydrates of Natural Gases.2nd ed.Macel Dekken Inc.,New York,pp.59.

Sloan ED,1998b.Clathrate Hydrates of Natural Gases.2nd ed.Macel Dekken Inc.,New York,pp.477.

Sloan ED,1998c.Clathrate Hydrates of Natural Gases.2nd ed.Marcel Dekker Inc.,New York,pp.111.

Sloan ED,2003.Fundamental principles and applications of natural gas hydrates.Nature,426:353–359.

Tohidi B,Anderson R,Clennell MB,et al.,2001.Visual observation of gas-hydrate formation and dissociation in synthetic porous media by means of glass micromodels.Geology,29:867–870.

Uchida T,Ebinuma T,Ishizaki T,1999.Dissociation condition measurements of methane hydrate in confined small pores of porous glass.Journal of Physical Chemistry B,103:3659–3662.

Uchida T,Ebinuma T,Takeya S,et al.,2002.Effects of pore sizes on dissociation temperatures and pressures of methane,carbon dioxide and propane hydrate in porous media.Journal of Physical Chemistry B,106:820–826.

Uchida T,Lu HL,Tomaru H,2004a.Subsurface occurrence of natural gas hydrate in the Nankai trough area:implication for gas hydrate concentration.Resource Geology,54:35–44.

Uchida T,Takeya S,Chuvilin EM,et al.,2004b.Decomposition of methane hydrates in sand,sandstone,clays,and glass beads.Journal of geophysical research,109(B05):206–218.

Uchida T,Tsuji T,2004.Petrophysical properties of natural gas hydrates-bearing sands and their sedimentology in Nankai trough.Resources Geology,54:79–88.

Wilder JW,Seshadri K,Smith DH,2001.Modeling hydrate formation in medium with broad pore size distribution.Langmuir,17:6729–6735.

Zhang P,Wu QB,Wang YM,2009.Comparison of the water change characteristics between the formation and dissociation of methane hydrate and the freezing and thawing of ice in sand.Journal of Natural Gas Chemistry,18:205–210.

Zhang P,Wu QB,Pu YB,et al.,2010.Water transfer characteristics during methane hydrate formation and dissociation processes inside saturated sand.Journal of Natural Gas Chemistry,19:71–76.

Sciences in Cold and Arid Regions2014年4期

Sciences in Cold and Arid Regions2014年4期

- Sciences in Cold and Arid Regions的其它文章

- Thermal conductivity of reinforced soils:A literature review

- In-situ testing study on convection and temperature characteristics of a new crushed-rock slope embankment design in a permafrost region

- Advances in studies on concrete durability and countermeasures against freezing-thawing effects

- Cooling effect of convection-intensifying composite embankment with air doors on permafrost

- Case studies:Frozen ground design and construction in Kotzebue,Alaska

- Thermal state of ice-rich soils on the Tommot-Yakutsk Railroad right-of-way