U.K. Needs Clear Choice on China Relations

By+JOHN+ROSS

CHINA and Britain have potentially one of the worlds most fruitful international economic relationships. Not only do they account for 16 percent of world GDP, but their two economies are mutually complementary rather than competitive.

China is now the worlds largest industrial producer, having overtaken the U.S., whereas the U.K. is highly specialized in financial and other services. Industrial sectors where the U.K. still retains a strong position, such as high-end pharmaceuticals, are not really threatened by competition from China. These areas will take China a signifi cant period to build its own technology, expertise, and resources. Simultaneously, China has the worlds most cost effi cient medium technology manufacturing and the U.K. is one of its top 10 export markets.

China possesses some of the worlds most powerful banks, ICBC being ranked as the world leader on many ratings. It also has the worlds largest annual savings – the raw material of the fi nancial service industry. But Chinas banks are extremely interested in internationalizing themselves, while London is highly specialized as a center for international fi nancial operations. China wants to increase the RMBs international use, and London is by far the worlds most important foreign exchange dealing center, with a turnover higher than New York and Tokyo combined. Britain, therefore, is an ideal center for Chinas international RMB operations.

The potential for economic cooperation between the two countries was apparent during Chinese Premier Li Keqiangs visit to Britain this year. Multi-billion dollar deals were signed, together with 40-plus intergovernmental agreements and business pacts, covering multiple areas like energy, high-speed trains and finance. After a period of frosty relations, caused by David Camerons meeting the Tibetan separatist leader the Dalai Lama, political relations between China and Britain warmed up significantly this year – with the U.K. Prime Minister and other British ministers being welcomed to Beijing for offi cial visits.

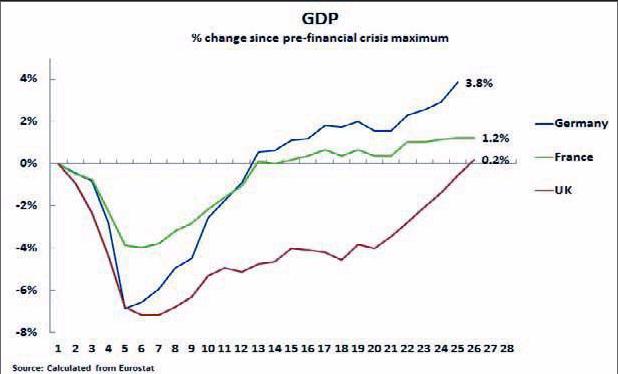

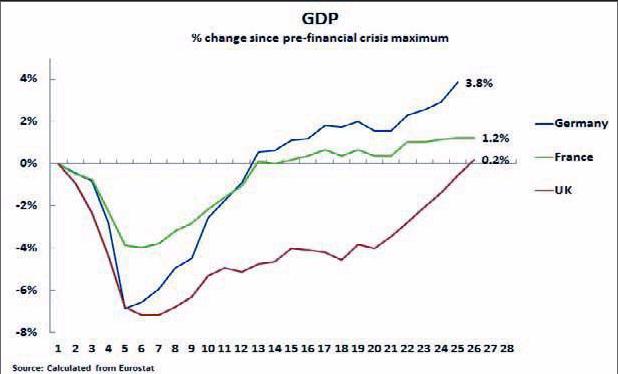

Given the mutually complementary nature of the two economies one might think it would be easy to arrange a“win-win” outcome. This is particularly important for the U.K., as its economy has performed worse than the two other largest European economies, Germany and France, since the international fi nancial crisis began. As shown in the chart, since their pre-crisis peaks, German GDP has increased by 3.8 percent, France by 1.2 percent, but the U.K. by only 0.2 percent.

But, regrettably, Britain periodically continues to shoot itself in the foot over its relations with China – inevitably causing damage to the U.K. economy. This has become a more serious obstacle than technical economic questions which remain to be fully resolved – for example the rules on Chinas banks setting up branches in London. To show the issues involved it is clarifi catory to make a comparison with Germany.

Among the reasons Germany came through the international fi nancial crisis much more successfully than the other major European economies is undoubtedly its strengthening economic relations with China. Germany and China worked out an international division of labor which plays to the strengths of both economies – an approach which should be copied by the U.K..

Germanys strength is in manufacturing. It is highly specialized in the production of very high quality machine tools and other investment equipment. China needs to import large quantities of these to upgrade its industrial structure. Simultaneously, China is by far the worlds largest and most cost efficient producer of intermediate technology goods – German imports of which help keep its own infl ation at a low level. Chinese companies, such as construction equipment manufacturer Sany, have been investing in Germany to gain access to its expertise. Germanys Chancellor Merkel has consciously kept the momentum of relations with China moving forward by making seven offi cial trips to China.

As Europes economy will undoubtedly suffer a setback, due to the negative side effects of the Ukraine crisis, with its damaging sanctions and counter sanctions, creating the best possible relations with China is even more important for all European economies including the U.K..

British Prime Minister Cameron and Finance Minister Osbornes trips to China earlier this year, together with Li Keqiangs visit to the U.K., therefore made it seem as though a new relatively smooth and fruitful period would be opened in Sino-British relations. But unfortunately, instead of building on this, Britain decided to shoot itself in the foot again by creating the same type of problems as with the Dalai Lama – this time over Hong Kong.

This immediate issue was the decision of the U.K. Parliaments Foreign Affairs Committee to “investigate” the new 2017 system of election of Hong Kongs chief executive. Not only does the U.K. no longer have legal rights in Hong Kong, since Britains former colony returned to China in 1997, but the U.K. committees moral position on this looks ridiculous. Britain ruled Hong Kong for 150 years. It never introduced the election of Hong Kongs chief executive, the governor, in any form whatever. If Britain thought there were some vital issue involved in the method of deciding Hong Kongs head of government, Britain could have introduced that system while it was ruling Hong Kong – it did not.

The reality is the actions of the U.K. Parliaments Foreign Affairs Committee damage the interests of the people of Britain – who have most certainly not been consulted over the matter. Given the real choice, “is it more important to secure jobs and incomes in Britain through good relations with China, or to make completely ineffectual statements on a matter over which the U.K. has no jurisdiction?” a crushing majority of the British public would undoubtedly chose the former.

It is a great pity that some British political authorities began to partially deviate from the fruitful track that was re-established earlier this year. At that time China-U.K. relations looked like they were getting onto a mutually benefi cial track. Regrettably by attempting to interfere in the internal affairs of China again, some people in Britain damaged this mutually advantageous path.

This is not to the advantage of either side. But, given the relative contemporary economic strength of the two sides, the U.K. would suffer from this path much more than China. It is therefore strongly to be hoped that U.K. politicians stop creating obstacles to better relations, and that China and Britain pursue the path to building on the different but complementary economic strengths that were established earlier this year.