IT Transforms Medical Services

By+staff+reporter+LUO+YUANJUN

SINCE mid-June 2014 the emergency room of the Nanhai District Peo- ples Hospital in Foshan City, Guangdong Province, has been spared the hectic crowds normally seen over previous years. According to head of the emergency ward Guan Ziyun, the emergency room receives 400 patients every day, with a record high hitting 810. But overcrowding has been greatly alleviated in the district since big-data technology was introduced for medical service providers in late April.

By the end of April, the Nanhai District Residents Health Records Management Platform had gone into operation, giving registered users access to such information as previous visits to hospitals, prescriptions and the results of earlier health checks. This enables doctors to make better and faster diagnoses of patients rushed into an emergency room, and provide the required precise treatment.

Big Data Transforms the Healthcare Sector

The Nanhai platform is one example of Chinas campaign to informatize its healthcare sector. In 2010, the Chinese government set the goal of establishing a three-tier healthcare information platform system at national, provincial and prefectural levels, with two health data bases – patients electronic archives and electronic case histories. Today, most hospitals in China have embraced big data as a means to improve services and competitiveness.

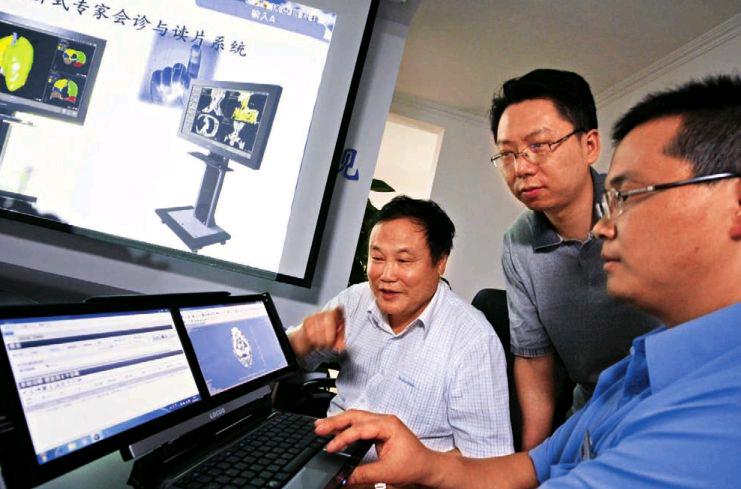

Big data is part of the incorporation of Internet technologies into medical services, which, in a nutshell, is about placing onto the Internet such objectives as collection and supervision of health data, diagnosis, treatment and consultation, with the help of wearable intelligent medical apparatus. In this way, such data is not confined to a single paper file within a particular hospital, but instead flows freely, shared by healthcare providers in different locations who need it.

Training is required for this informatization campaign, particularly for medical workers in rural areas. Last May, 100 rural doctors attended a training course in Chengmai County, Hainan Province, to learn, among other skills, how to operate intelligent medical equipment that measures and analyzes major physiological indices such as blood pressure, blood sugar and heart beat. When connected to computers, such information can be uploaded to a cloud server accessible to hospitals across the country, whether large hospitals in mega-cities like Beijing or small ones in rural communities. The information enables doctors to track the health history of a patient and make better diagnosis.

So far this technology has found its way to all of the 2,476 villages in Hainan, gathering health data for about 5 million rural residents in the province. It connects medical care organizations at the county, township and village levels, and helps patients make informed decisions about where to seek appropriate services. Based on such computerized analyses, village physicians advise patients to either undergo treatment at the community infirmary or go to bigger facilities in town or in nearby cities.

In Luoyi Village, Chengmai County, for instance, health files have been set up for 4,828 of its residents, and 31,065 entries from checkup results have been uploaded onto the Internet. Li Shouxing, a physician at the village clinic, welcomes the change. The old way of keeping records, with case histories using notebooks and pens, demanded extensive storage space and hindered information sharing.

Seeing Doctors Online

By the end of 2013, more than 2,000 medical-care apps were in use in China, with over 500 companies developing such programs. The most used app is Doctor Spring Rain, a mobile app that enables users to describe their medical condition to professionals for free consultations.

Wang Rui, a clerk with a media company, is a user of this program. “By clicking on a certain part of the human body shown on the screen, you see a list of symptoms. Your selection then leads you to possible causes and related treatments. If you cannot fix on definite answers about your condition, you could take your case to one of the over 5,000 doctors at top-rate hospitals across China via voice messaging or photos,” Wang explains.

Doctor Spring Rain was developed by Beijing Spring Rain Software Co., Ltd. Founded in mid-2011, the company runs a mobile health database, whose feeds are all attributed to authoritative medical canons and official databases. Users have now topped 20 million. This app involves over 15,000 doctors with leading and Class-Two hospitals across China, who field 25,000-plus healthrelated questions on a daily basis.

“Daily visits to the Doctor Spring Rain platform outnumber those of any Chinese hospital. And a reply is to be expected within 30 minutes of receiving the question,” said Spring Rain CEO Zhang Rui. “Once a question is raised, our system first forwards it to a doctor in the relevant division who is free. Doctors are recompensed on the basis of user evaluations. This is how you can expect prompt replies even at midnight.”

Another advantage of the app, Zhang said, is that it relieves pressure on star hospitals like the Peking Union Medical College Hospital, by diverting some patients to less-visited Class-Two hospitals. “What we do is tap into the resources of available doctors, mobilizing them to provide services online,”Zhang said, adding that 95 percent or more cases brought into doctors offices are not complicated, with solutions possible through online interaction. This is what Spring Rain specializes in – diagnosis of minor ailments and health consultations.

The Internet has also significantly boosted interaction between doctors and patients. Under current laws in China, a licensed health care worker must practice at an actual (not virtual) medical institution. This rules out online hospitals. But thanks to information technologies, patient information about previous visits to different stationary hospitals has become available, accessible through the computer or handset of a physician a person consults, in person or online. For many conditions, such information, along with online communication, is sufficient for a doctor to come up with targeted solutions without meeting a patient face to face.

A Big Emerging Market

According to an ABI Research report, the market value of wireless online medical services will reach US $1.34 billion by 2016, when 30 million mobile gadgets will be connected to wireless medicalcare networks, and wearable medical sensors will number 100 million. These sensors might be a heart beat monitor, a blood-pressure gauge, or a bracelet gauging sleep quality. The data collected is automatically transferred by email to the wearers and their doctors for reference and analysis.

In the current situation of a grim imbalance in medical resource distribution, online services help meet the vital need of patients for better communication with their doctors. Surveys show that 64 percent of people are willing to try and pay for online medical services; 74 percent are open to wearable medical apparatus, all of them willing to pay; and 46 percent express a desire for medical consultations via mobile apps or networks, 75 percent of them willing to pay for the service.

Channeling of mobile medical services, voice messages and text messages is expected to give way to smart phones and mobile networks, with the latter taking predominance. Though most people accept a price tag for mobile medical services, cost remains a make-or-break factor. Service providers are therefore advised to levy low or no fees on customers, and resort to other operations for profits.

At present, medical apps in China are in three categories: the first is about selfdiagnosis and remote consultation with doctors, as represented by Spring Rain; the second features disease management and post-surgery rehabilitation, Haodf. com being one example; and the third focuses on medication. An example is DXY, which offers advice on medication and the reading of medication guides.

According to a consultant with iiMedia Research, a world-famous third-party data mining and integrated marketing agency on the mobile Internet, mobile medical care has to overcome many obstacles before it can secure a footing in China. At present, medical resources still fall short of demand in the country, the accessibility level of public hospital information systems remaining low. Users of mobile healthcare services are relatively few and not active. How to generate a profit is also an issue. Spring Rain charges for online services, but paid customers account for only 5 percent of its clientele, and all their contributions go to the doctors. The question-and-answer function is free for users, but the website actually reaches into its own pocket to pay the responding doctors. The company seeks to make up the loss by soliciting advertisements for health products, like those for mothers and babies.

No matter what difficulties might be encountered at the startup stage, it is undeniable that the Internet is trending in the health-care sector, as it is in many other industries around the world.