China’s Changing Development Pattern

By+JOHN+ROSS

DATA available on the worlds two largest economies, China and the U.S., for 2013 provide an opportunity to take stock of Chinas immediate economic prospects and the more general challenges facing its economic development strategy.

The short-term trends are clear. Chinas economic growth decelerated marginally from 7.8 percent in 2012 to 7.7 percent in 2013. U.S. economic growth slowed more substantially – from 2.8 percent in 2012 to 1.9 percent in 2013. In money terms, Chinas GDP in 2013 grew by US $1,030 billion and U.S. GDP by US $560 billion. Western media hype about U.S.s “strong recovery” and Chinas “major slowdown” was therefore the opposite of reality.

More significant for Chinas development strategy than simply one years fi gures are the fundamental trends in the world economy. These show that since the beginning of the fi nancial crisis the developed economies have entered what is best described as a “Great Stagnation.”This necessarily has major consequences for Chinas development pattern.

During almost all the first three decades of Chinas reforms from 1978 to 2007, the last year before the fi nancial crisis, Chinas economic development was aided by tailwinds from the world economy. China skillfully utilized these to achieve annual economic growth of 9.9 percent – compared to the worlds 3.0 percent and advanced economies 2.7 percent.

But from 2008 tailwinds turned into headwinds. Even assuming the IMFs latest estimate was achieved in 2013, growth in the advanced economies in the six years after 2007 averaged only 0.6 percent. As advanced economies were traditionally Chinas largest export markets this sharp deceleration necessarily had negative consequences for Chinas previous growth model.

Given the scale of slowdown in advanced economies, China came through this rather well. Chinas economic growth slowed only to an average 9.0 percent in 2007-2013. Chinas growth lead over the high income economies actually increased – in 1978-2006 China grew an average 7.2 percent more rapidly than the advanced economies, while in 2007-2013 this increased to 8.4 percent.

Taking only bilateral comparisons with the U.S., over the whole period 2007-2013 the U.S. economy grew by only 6.0 percent while China grew by 67.7 percent. Since the beginning of the fi nancial crisis, China overtook the U.S. to become world number one in trade in goods, in industrial production, and in annual savings – the finance available for investment.

But despite China coming through the international fi nancial crisis more successfully than other major economies, it would be utopian to imagine it would suffer no bruises from the worlds greatest economic crisis for 80 years. China therefore simultaneously faces the challenge of repairing any economic damage and preparing for the next period of economic development – as will be seen the two coincide.

Internationally there is no reason to anticipate sharp acceleration in the advanced economies. In all major developed economies investment, economic growths main driver, remains below pre-crisis levels. In the last fi ve years the U.S. and EU persistently underperformed projections made in advance by the IMF – meaning its 2.2 percent projection for advanced economy growth in 2014 is probably best taken as an upper bound. In contrast, despite some slowing, economic growth in developing economies remains more rapid due to higher investment levels, and the IMF projects 5.1 percent growth in 2014.

The consequences for Chinas trade are evident. Towards the end of 2013, in inflation adjusted terms, imports by developed economies were 7.0 percent below precrisis levels while imports by developing economies were 29 percent above them. Reorientation of Chinas trade towards developing economies will therefore continue.

However, this requires continuing change of Chinas internal economic structure. Many of Chinas exports to developed economies were components for advanced industries, Chinas labor costs being low compared to theirs. But outside parts of Asia such advanced manufacturing does not exist in developing economies, and Chinas wages are increasingly high compared to many developing economies. For example, China now has a higher per capita GDP than all developing countries in Southeast and South Asia except Malaysia.

China therefore cannot compete in developing economies through low wages any more. It can only maintain a competitive edge through continuously developing “cost innovation” – securing competitive prices not via low wages but by technological development and management strength. This, however, requires growing investments in technology, capital equipment embodying it, R&D, new capabilities such as high level brand development and management training.

This interrelates with the main challenge facing Chinas domestic economy. Internationally the fact that trade plays a bigger role in Chinas economy than in the U.S. maintains strong competitive pressure on Chinese companies, forcing them to increase their effi ciency. But the transition from competitiveness achieved via low wages to that based on innovation and technology is a reason why, as economies become more advanced, investment plays an increasing role in their growth. International studies show that on average, investment accounts for 57 percent of growth in an advanced economy compared to 52 percent in developing economies. As investment must be financed through savings by companies, households and government, maintaining high savings and ensuring their transformation into investment is Chinas most fundamental macroeconomic task.

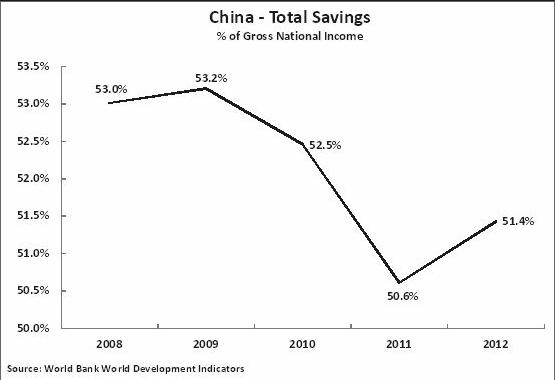

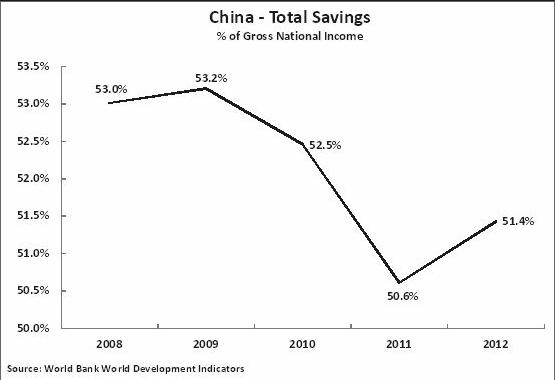

It is in this area that the international fi nancial crisis created economic problems for China. As the chart shows, under its impact Chinas savings rate fell from 53.2 percent of Gross National Income to 51.4 percent in 2012 –the latest available data. Industrial profi tability rose less rapidly than GDP.

There is no indication that savings levels rose signifi -cantly in 2013. As savings are the supply of capital, given these have fallen, either interest rates, the price of capital, must rise or the demand for capital, that is investment levels, must fall.

Consequently Chinas rising interest rates in 2013 and 2014, increasing the cost of company and government borrowing, and in June and December 2013 creating interest rate spikes in interbank lending, reflected this. It is therefore a major challenge to rebuild Chinas savings rate to finance the high levels of investment needed to upgrade its development path.

This also affects issues such as environmental protection. Greater environmental protection, to eliminate smog for example, requires high investment given that non-polluting power stations, factories etc. are more expensive than polluting ones.

In only a decade China, by international classifications, will become a high-income economy whose growth is more dependent on investment in innovation, both technological and management, than on low wages. China came more successfully through the international fi nancial crisis than any other major economy. But China continues to face for a signifi cant period a “Great Stagnation” in the advanced economies. Its development priorities need to refl ect this.