Beijing’s Green Courtyard

By+staff+reporter+DANG+XIAOFEI

NANLUOGUXIANG Street, one of the oldest communities in Beijing, is usually thronged with tourists. One of the most captivating features of the area lies in the old courtyards. However, due to disrepair and poor living conditions, this unique construction, the symbol of Beijing, is on the brink of disappearing.

To fight this threat, the old constructions are transformed to meet the de- mands of the 21st century. The No. 3 courtyard of Banchang Alley in Nanluoguxiang is an example of this. A “water recycling” concept integrated into the repair work has allowed the courtyard to operate in a green way.

Saving Rainwater

This is an average courtyard, free from the luxuries reserved for the rich; but the tranquility as well as the vitality of the compound is palpable from the first step inside. Walking through a short passage and a circular entrance, you find yourself in a small courtyard where two big trees stand. The newly-decorated main house in the northern quarter of the courtyard, two wing houses to the east and west, and a house opposite the main building constitute a standard Beijing courtyard.

“This courtyard was passed down from my grandfather. It is home to three generations of our family,” said the courtyards owner, Chen Geng. “Three years ago, it became dilapidated and wasnt fit for living in, so I decided to knock it down and rebuild it.”

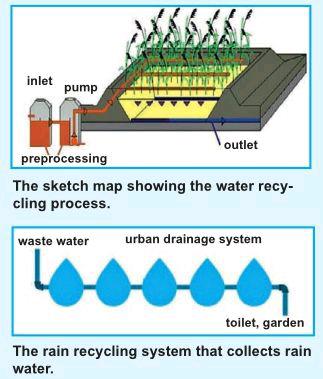

After surveying the construction, Sino-Ocean Land Holdings Ltd. concluded that the construction needed moderate repairs instead of full-scale reconstruction. Its proposal included the courtyards inclusion into its zerocarbon demonstration project, which has sponsored environmental renovation in over 100 communities so far, and covers all expenses. In the courtyard, the alterations consisted of three parts– rainwater collection and recycling, the construction of an artificial wetland for wastewater treatment and adaptations to the courtyard environment – aiming to make the old courtyard livable as well as environmentally friendly in the areas of water conservation, emission reduction and environmental improvement.

The original courtyard had no watersaving facility. During the renovations, the courtyard was paved with water permeable bricks. “They look like ordinary gray bricks but are actually made of a special material with extraordinary permeability,” Chen Geng explained. “No matter how heavy the rain is, puddles of stagnant water never form.”

In this water collection area, which is essentially a well, the elevation facade is tiled with seepage-control bricks that guarantee rain flows to the floor. The base is a layer of sand about 50 millimeters thick, air permeable but waterproof, which can prolong the quality guarantee period of the collected rainwater. “The natural rainwater is first channeled to the well,” Chen Geng said. “After several rounds of filtration, it is used to irrigate flowers and plants and in fish ponds.”

“Preliminary calculations show that the system can collect and process as much as eight tons of rainwater annually,” explained Wang Yutian, a staff member at the Strategic Development Department of Sino-Ocean Land, “and the maintenance cost is next to nothing.”

Artificial Wetland

“Compared with previous projects, the highlight of this one is the ‘artificial wetland technology that we have adopted for the first time in transforming old constructions,” said Tu Zheng, general designer of the courtyard from Sino-Ocean Lands R&D Department.“The collecting, recycling, filtrating and extracting systems allow the waste water to be used in the courtyard for aquatic plants and fish tanks; thus, water is saved and the environment is improved at the same time.”

The artificial wetland system usually consists of artificial soil and aquatic plants. It is a special eco-system including soil, plants and microbes. “Family wastewater (sewerage from the flush toilet excluded), including water for personal sanitation and washing clothes, is pumped to the wetland in the courtyard. After biological cleaning, it is directed through pipelines for usage. Though not potable, it can be used to flush toilets and clean floors,” said Chen Geng.

Chen demonstrated the workings of the system. The processed water constantly flows into the flowerbed and fish pond, saving water and adding vitality to the courtyard.

“According to calculations, the artificial wetland can collect 80 tons of sewerage water a year. If it is recycled for watering plants, cleaning floors and flushing toilets, it will reduce fresh water usage by as much as 50 tons a year,” said Wang Yutian.

“The quality of life for residents here has improved on numerous levels,” said Chen Geng, “The system saves water and reduces my bills, and is also in line with the idea of low carbon emissions and eco-living.”

As a cosmopolis, Beijings water consumption is prodigious. According to statistics released by the Beijing Water Supply Bureau in 2013, Beijings yearly average water consumption reached 3.6 billion tons; but the city has a total volume of water resources of only 2.1 billion tons a year, meaning there is a deficit of about 1.5 billion tons. Each resident of Beijing enjoys less than 100 tons of water resources a year, less than 5 percent of the average level of China. This makes Beijing one of the most water-starved cities in China.

Preserving the Past

In addition to the water conservation system, the restoration project adopted several energy-saving and emissionreduction measures. For example, it installed solar panels that can power the pumps in the daytime and the courtyard lighting in the evening. Watersaving faucets and LED lights were also introduced. Whats more, along with this modern technology, the traditional features of Beijings courtyards have not gone neglected.

“As a unique construction in Beijing, the courtyard is the body representing the spirit of the ancient city, and allusions to Chinese culture can be found in its every detail. The layout and design, after hundreds of years of improvement, perfectly fit the special climate of the city. However, it cant meet the ‘livabledemands of modern times,” said Tu Zheng.

“Therefore, we deliberately considered the lifestyle of old Beijingers during the alterations,” said Duan Tao, deputy general manager of the Strategic Development Department of SinoOcean Land, “We used stones with intricate patterns to build the water feature and old-fashioned wall lamps to preserve the original constructions style as far as possible.” Duan and his colleagues strive to apply eco-friendly technology, meanwhile finding a balance between carrying forward the traditional culture, facilitating a comfortable modern life and conserving energy.

In addition, a new gray brick wall was erected at the entrance of the courtyard where the original screen wall used to stand. It is an important part of the courtyard but was knocked down dozens of years ago.

The total expense of the renovation work reached RMB 300,000, not a humble sum, but “similar restorations will continue,” Wang Yutian said.

While constructing green buildings, Sino-Ocean Land is also devoted to promoting a green life style through its non-profit demonstration projects in communities. With its money- and resource-saving function as well as its beautification effect, its expected that the water-saving renovation model will be adopted across Beijings old courtyards.