Invisible Hands:Gestures of Curating

by+Meng+Yuan

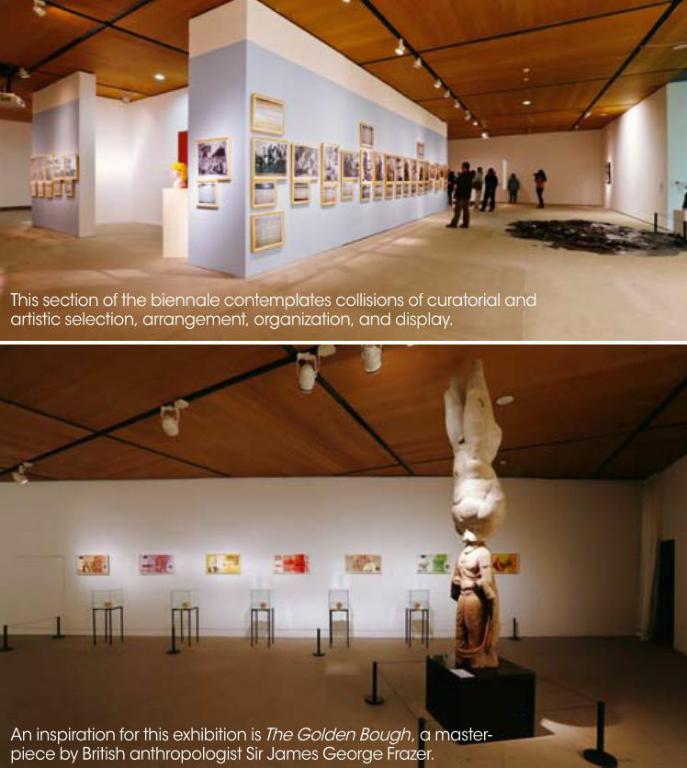

On February 28, 2014, the 2nd CAFAM Biennale entitled The Invisible Hand: Curating as Gesture was held as an exhibition featuring experimental spirit as well as flavors crossing different cultures and regions. The invisible hand, an economic term coined by Adam Smith in his Wealth of Nations, is employed here to refer to the function of the curatorial practice. The invisible hand in this context is more like an “institution” in which contemporary art strives to find its own appropriate position.

Each section of the biennale shows compromise between artists and curators after their conflicts and wrestling. Chinese artist Liu Xinyis suggestion boxes are spread across the exhibition hall of The Code of The Golden Bough-Economics curated by Hu Danjie, while Singaporean artist Heman Chongs black cards can been found everywhere in On Ambiguity and Other Forms to Play With by Veronica Valentini. Like Marcel Duchamps urinals, suggestion boxes affirm contemporary art but satirize art institutions and the black cards defy and protest museums. The suggestion boxes and black cards, just like the seeds sown by artists, gradually flourish above art institutions.

Curators employ spectators as coordinators between the curatorial system and contemporary art. In the section No Puppet Is Dumber Than Its Puppeteer by Londoner Kit Hammonds, he invites the audience to bridge curatorial institutions and contemporary art, a practice forcing contemporary art to be recognized by curatorial institutions. For instance, in South Korean artist Yva Jungs photography, one shot is her taking an elevator when suddenly, wooden luggage she was carrying dropped and items within it were scattered around, causing people to spontaneously try to help her. But by repeating the accident many times, passersby produce a wide variety of reactions.

Ventriloquists: Introduction by Yu Zhengda employs eight screens, each equipped with earphones. In videos ap-pearing on the screens, the artist stands behind different foreigners speaking Chinese sentences as the foreigners attempt to repeat his speech. “A beautiful sentence in Chinese becomes a funny and ridiculous fragment of words, with new connotations,” Yu Zhengda explains.

Curator Weng Xiaoyu from California College of the Arts, San Francisco, named her section Parliament of Things, or, Wandering in a Continuously Bewildering Wonder, an obscure title which she chose to make it hard for spectators to remember her curatorial intentions so as to exert as little influence as possible on the audience. Through this method, Weng expresses that contemporary art is accepted by curatorial institutions. Photos and splicing in Assembly Instructions by Alexndre Singh demonstrate that artists appreciate art in institutions such as museums but create in fields outside the institutions. Ultimately, artists work is sold and returns to the art market. He believes an integral part of the working process of artists is to go in and out institutions from time to time. His last painting portrays a hand with a few coins, indicating the market value of art is little and the real value of art lies in the process of creation. Li Ran discusses the relationship between history and Freuds ‘id in a space of glass in Mondrians style. It is good to clearly understand history, but ‘id should not be replaced by ‘other, accords to Li. Obeying too many rules will cause artists to lose themselves. Without firm ideals, the artists wings will be broken by ‘the invisible hand.

While others try to wrestle control away from “the invisible hand” of institutions, Harrell Fletcher from the U.S. made use of institutions to build a museum titled The American War as a work in this exhibition. By doing so, he deftly unravels the conflict between curatorial institutions and contemporary art. He makes use of institutions to fight against institutions and at the same time creates art that can be considered one half of two shaking “invisible hands”