Multi-visceral resection of locally advanced extra-pancreatic carcinoma

Darren R Cullinan and Stephen W Behrman

Memphis, USA

Multi-visceral resection of locally advanced extra-pancreatic carcinoma

Darren R Cullinan and Stephen W Behrman

Memphis, USA

BACKGROUND:Multi-visceral resection for extra-pancreatic carcinoma is an uncommon procedure that may offer palliation and potential cure but must be balanced against the risk for morbidity and mortality.

METHODS:A retrospective analysis was made of patients who had undergone multi-visceral resection of non-pancreatic carcinoma. Factors influencing this procedure included histology, pathologic confirmation of pancreaticoduodenal invasion, tumor clearance, peri-operative morbidity and outcome.

RESULTS:Sixteen patients haden blocresection including a Whipple procedure (6 patients) and a distal resection (10). Primary pathology mostly originated from the stomach and adenocarcinoma was predominately histological. An R0 resection was made in 13 patients, and actual cancer invasion or abutment into the pancreas or duodenum was confirmed pathologically in 11 patients. Twelve patients suffered from at least one complication. Ten patients required therapeutic intervention for complications. There were 2 in-hospital deaths. The median survival of deceased patients was 7.5 months. Six patients are alive at a median of 21 months, and 4 patients have no evidence of disease to the present.

CONCLUSIONS:Multi-visceral resections for extra-pancreatic carcinoma are associated with substantial morbidity that requires therapeutic intervention. Clinical determination of pancreaticoduodenal abutment and achievement of tumor clearance is excellent. Survival with and without recurrent disease is often limited, supporting that it is necessary to cautiously perform the aggressive procedures in consideration of neoadjuvant therapy.

(Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 2014;13:198-202)

pancreas;

surgery;

cancer;

multi-visceral

Introduction

Multi-visceral resection (MVR) for primary pancreatic carcinoma that infiltrates surrounding organs has shown no significant increase in procedure-related morbidity and mortality compared with pancreatic resection.[1-5]In contrast, pancreatic resections includingen blocremoval of other primary carcinomas for tumor (R0) clearance are known to increase complications and death rate. Equivocal results could be obtained with respect to pathologically confirmed cancer invasion into the pancreas and duodenum, long-term survival, and cure.[6-8]Further, the use of pre- or post-operative adjuvant therapy in this cohort has been infrequently assessed and its impact on disease recurrence ill defined.[9]Current studies[6-12]on this population have involved small numbers of patients in whom these procedures are performed. We reviewed our experience with patients who had had MVR for extra-pancreatic carcinoma with a critical assessment of procedure-related morbidity and long-term survival.

Methods

The records of all patients who had undergone MVRs for extra-pancreatic carcinoma from 1998 to 2013 at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center were retrospectively reviewed after approval of the Institutional Review Board at Baptist Memorial Hospital in Memphis. The resections were made by specialists in an institution with a high volume of pancreatic resections. Pre-operative variables were investigated in terms of age, histopathology of carcinoma, tumor grade and neoadjuvant or adjuvant therapy. Intra-operative data included procedure type, the number of resected organs exclusive of the pancreas, the accuracy of surgeon-assessed invasion of or abutment to the pancreas and/or duodenum, consistency of remnant pancreas, operation time, blood loss and transfusion. In the present study, microscopic cancer abutment to the pancreas was considered as equivalent to invasion since an R0 resection would have otherwise been unlikely. Post-operative results were critically analyzed with respect to overall and pancreas specific morbidity. Complications were defined by the Clavien-Dindo severity grading system with a focus on therapeutic intervention including percutaneous catheter drainage or reoperation.[13]Other variables included pathologic confirmation of R0 resection, post-operative length of hospital stay and survival.

Results

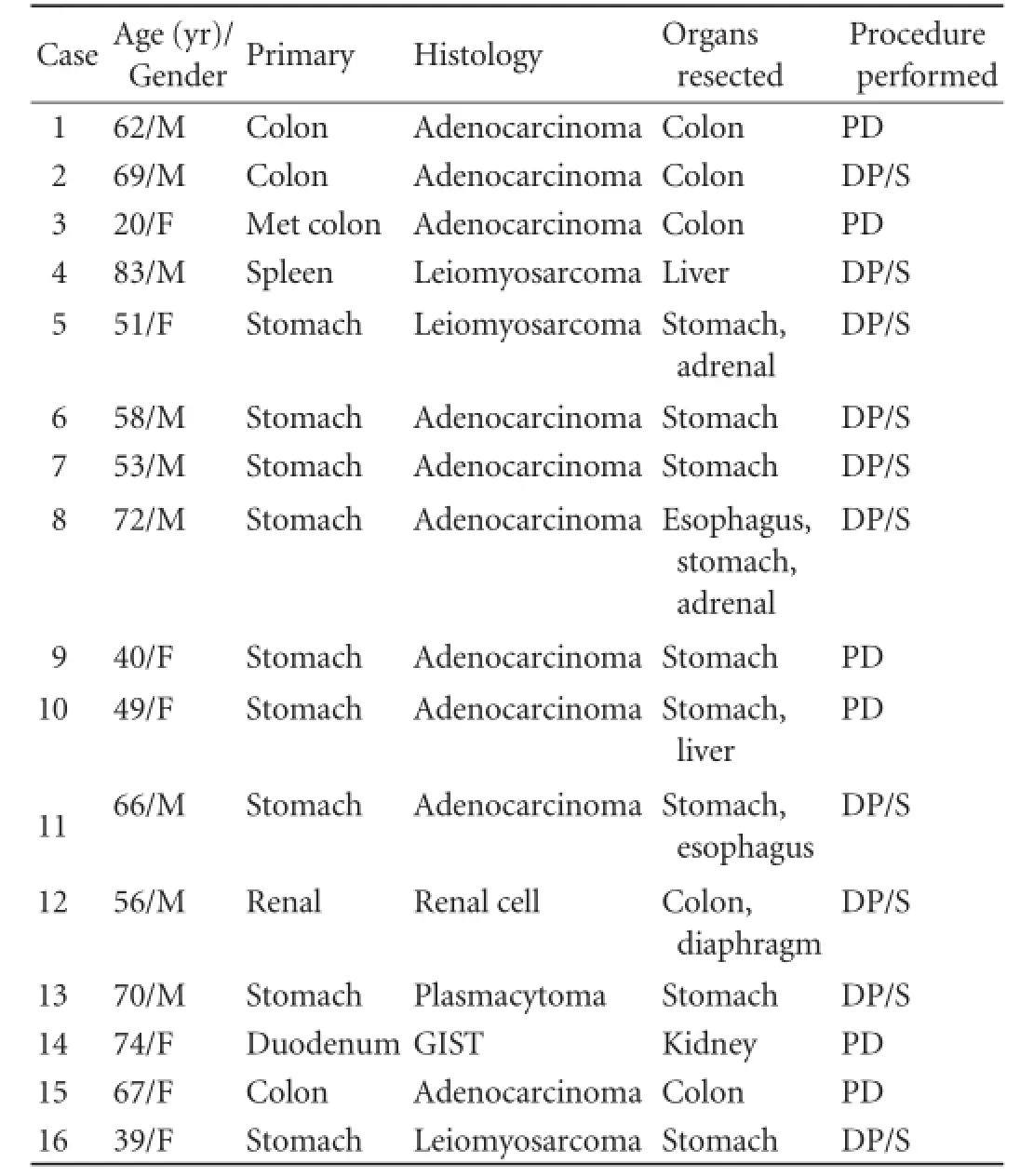

Sixteen patients (9 males and 7 females) with a mean age of 58 years (range 20-83) had MVR for extrapancreatic carcinoma in a 15-year period. This resection included a pancreaticoduodenectomy (6 patients) and a distal pancreatectomy (10). The results of primary histopathology and procedures performed are shown in Table 1. Of the 10 patients with adenocarcinoma, all but one demonstrated poor (G3) tumor differentiation. Fourteen of 16 operations were performed for local invasion of the primary tumor. Two MVRs were performed for locally recurrent metastatic disease: one patient with recurrent colon cancer presenting as a peritoneal mass on the head of the pancreas and the other with recurrent renal cell carcinoma in the bed of the resected left kidney infiltrating local organs. Only four patients received neoadjuvant chemotherapy: one with metastatic gastric sarcoma, two with gastric adenocarcinoma, and one with a gastric plasmacytoma. One patient with gastric adenocarcinoma extending proximally into the esophagus also received preoperative external beam radiation therapy, and had a complete pathologic response to neoadjuvant therapy. Six patients received adjuvant chemotherapy after surgical extirpation. Three patients underwent MVR for known metastatic disease. Two patients with primary sarcoma (one spleen and one gastric) had a surgical resection for palliation of symptomatic splenomegaly and massive upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage respectively, and one patient had peritoneal recurrence from a previously resected colon adenocarcinoma. Onehalf of the study population had at least one co-morbid condition pre-operatively.

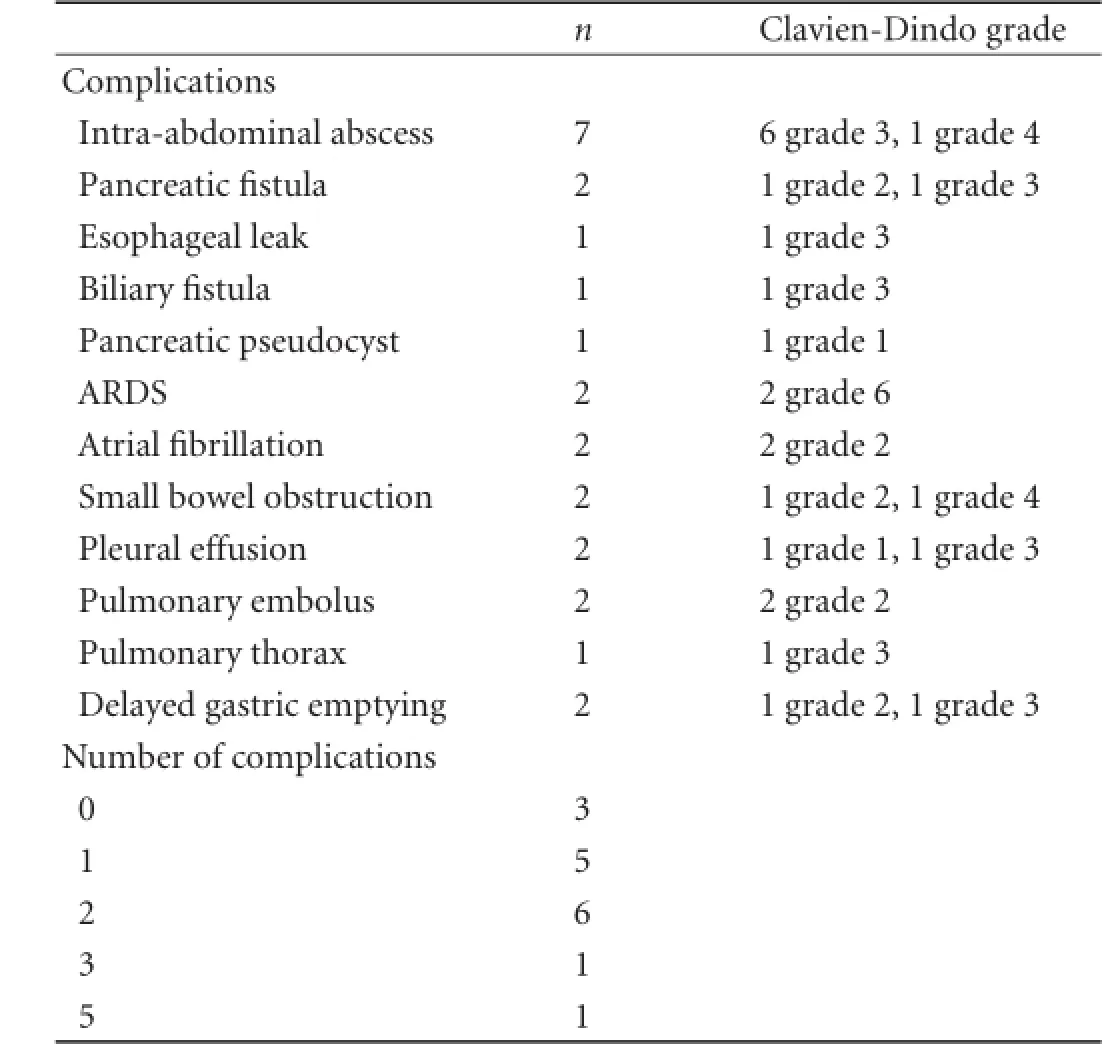

The mean operation time of the patients was 407 minutes (range 274-600) with a median blood loss of 400 mL (range 50-1500). Eight of the 16 patients received at least one intra-operative blood transfusion (mean 1.6 units) (range 0-6). The median time of intensive care and overall length of hospital stay were 3 (range 0-54) and 15 (range 8-54) days, respectively. All patients had a soft pancreatic remnant that was either reconstructed after a Whipple procedure or ligated after distal resection. After proximal resection, reconstruction was done in a duct-to-mucosa fashion. The death of two patients after surgery was due to their underlying comorbid illness. Thirteen patients had post-operative morbidity and one-half of the patients had more than one post-operative complication (Table 2). Intraabdominal abscess and pancreatic fistula predominated among the complications, which were characterized by Clavien-Dindo grade 3 or higher. Percutaneous catheter drainage for an abdominal complication was used successfully in 8 patients. Two patients required reoperation for drainage of an intra-abdominal abscess and management of a post-operative small bowel obstruction.

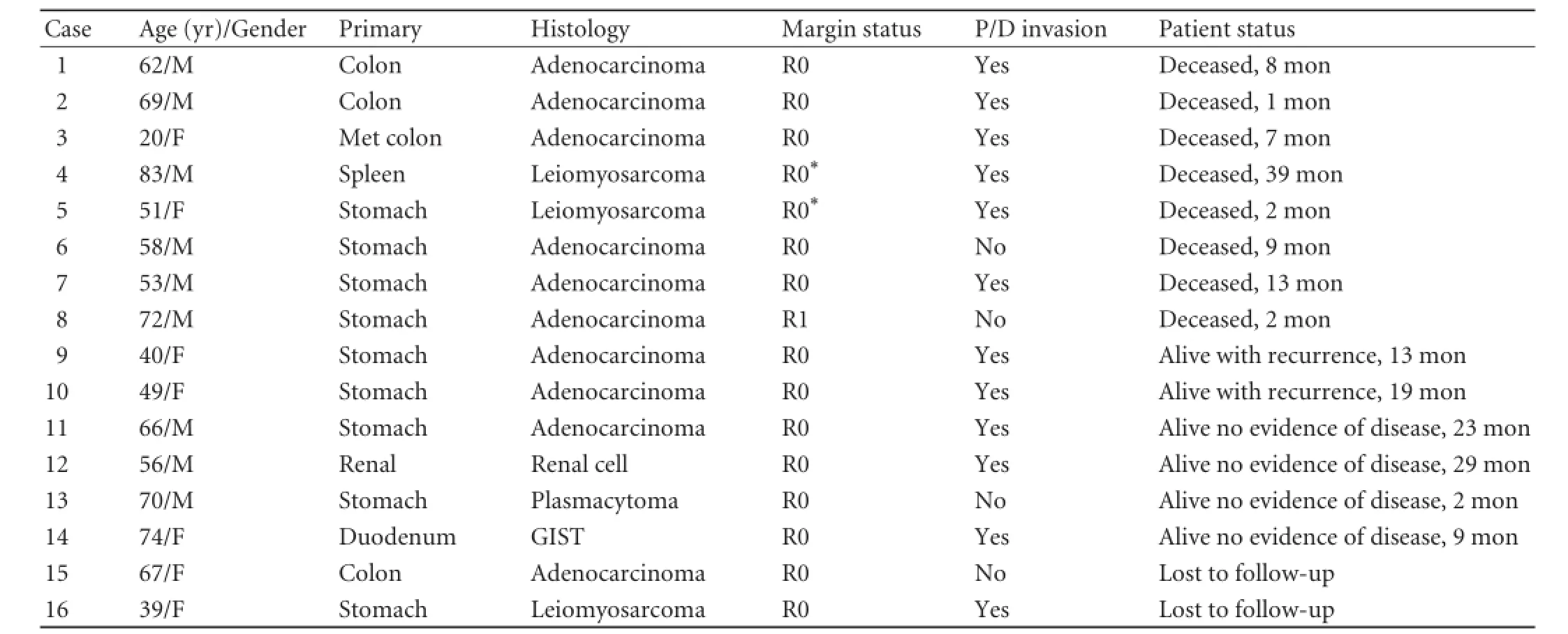

Margin status, pathologic evidence of pancreatico-duodenal invasion and current patient status are shown in Table 3. Thirteen patients (81%) underwent an R0 resection. Two patients had MVR because of metastatic disease (R2) to the liver as mentioned above. In both patients, however, resection of organs resulted in local tumor clearance with negative margins exclusive of metastasis. Direct tumor invasion or abutment into the pancreas or duodenum was confirmed pathologically in 11 patients. Pathologic analysis showed that a gastric plasmacytoma in one patient was extended into the spleen other than the pancreas. Two patients were lost to long-term follow-up. The median survival time of the 8 deceased patients was 7.5 months (range 25 days-39 months). All patients but those with inhospital mortality died from recurrent metastatic disease. Six patients are currently alive for a median of 21 months post-operatively. Of these patients, four have no evidence of other disease at 2, 9, 23 and 29 months including a patient with a complete pathologic response to neoadjuvant therapy.

Table 1. Tumor origin, primary histology, organs resected in addition to pancreas and type of pancreatic resection performed

Table 2.Post-operative morbidity and grade

Discussion

MVR for extra-pancreatic carcinoma represents formidable operations for intra- and post-operative complications and procedure-related death. Given the relative infrequency with which these operations are indicated and performed, it is imperative that peri-operative outcomes are judicially related to resources utilized, procedure-related morbidity and mortality and longterm survival, and that an appropriate risk/benefit analysis can be ascertained in the selected patient populations. Intuitively, one might anticipate an increase in pancreas-specific morbidity above and beyond that for the removal of primary tumor alone. The survival benefit after these procedures for carcinomas extraneous to the pancreas has been encumbered by small numbers and heterogeneous patient populations accumulated in a long period of time. Our results suggest that MVR ofextra-pancreatic carcinoma can be accomplished safely with an excellent tumor clearance rate. In our study, procedure-related morbidity was substantial and often required therapeutic intervention. Disappointed longterm survival suggested a multidisciplinary (neo)adjuvant treatment for the carcinoma.

Table 3.Margin status, histologic evidence of pancreaticoduodenal invasion and patient clinical outcome

MVR is suitable for extra-pancreatic carcinoma. Operative time and blood loss in our patients were modest as reported elsewhere.[5,6,10]Thus, blood transfusion during the procedures was minimized. There was no intra-operative death in our patients as reported previously.[6-12]

Given the potential for morbidity and mortality associated with concurrent pancreatic removal for extrapancreatic carcinoma, the sensitivity of intra-operative assessment of direct tumor invasion and its correlation with pathologic analysis are particularly important to ensure that pancreatic resection is not performed erroneously. In a series of 57 patients who underwent distal pancreatectomy for mesenchymal tumors as part of an MVR, Berselli et al[6]pathologically confirmed tumor invasion in only 26 (45.6%) patients. In 268 patients who underwent MVR for gastric carcinoma, 50 were subjected to simultaneous pancreatectomy. The incidence of direct tumor invasion (T4 disease) was only 14%.[7]Of 33 patients who had concurrent pancreatectomy for primary gastric carcinoma, 39% showed tumor infiltration into the pancreas confirmed histologically.[8]In contrast, in 24 patients of two series who had concomitant pancreatectomy for locally invasive colon carcinoma, 75%-85% had pathologically confirmed tumor invasion into the pancreas.[10,11]We defined microscopic abutment but not frank invasion into the pancreas and/or duodenum as invasion since R0 resection would otherwise not have been possible without a multi-organ resection. If a similar definition has been applied in the aforementioned studies, it is plausible that positive rates of invasion may have been higher. We noted that there is an correlation between assessment of pancreaticoduodenal involvement and final pathologic evaluation, suggesting that high magnitude procedures are necessary to obtain tumor clearance.

It is more encouraging to make an R0 resection when concurrent pancreatectomy is mandated for extra-pancreatic carcinoma. Martin et al[7]reported an R0 resection rate of 64% in 418 patients who had gastrectomy with additional organ resection. Fifty of the 268 patients in this cohort had a concurrent pancreatic resection although the number in this subset with an R0 resection was not noted. Piso et al[8]reported an R0 resection rate of 73% in 33 patients who underwent surgery for advanced gastric carcinoma. Two studies[10,11]showed an R0 resection rate of 75% and 100% in a total of 24 patients who underwent en bloc pancreaticoduodenectomy for colon carcinoma. In a study similar to ours, Varker et al[12]made an R0 resection in 55% of the patients who were subjected to MVR for locally advanced extra-pancreatic carcinoma. In our series, the R0 resection rate was 81%. Two patients with sarcoma metastatic to the liver had MVR for palliation with complete clearance of the primary lesion. Inclusive of these 2 patients, the R0 resection rate in our series was 94%. Despite technically challenging, these procedures may lead to complete tumor clearance.

We dismayed at the peri-operative morbidity encountered in these resections with complications of Clavien-Dindo grade 3 or higher. Surgical morbidity was particularly burdensome with pancreatic fistulae and intra-abdominal abscess. The complications were due to the extent of surgery and the soft nature of pancreatic remnant. The soft glands could be identified as a risk factor for fistulae and septic complications.[14-19]Percutaneous catheter drainage was particularly helpful as a tool for definitive management. The literature has been inconsistent with the procedure-related morbidity associated with these complex operations.[6,8-10,12]Curley et al[10]noted minimal morbidity including a zero incidence of anastomotic breakdown in 12 patients who had had pancreaticoduodenal or lateral duodenal resections for locally advanced colon cancer. Similarly, Pingpank et al[9]identified no pancreatic or biliary leaks in patients who had undergone both left and right pancreatic resections for tumors arising from upper abdominal organs with extension to the pancreas. Two series of patients having left en bloc pancreatic resections showed a procedure-related morbidity of 35%.[6,8]In another series of patients with locally invasive extrapancreatic carcinoma, a procedure-related morbidity rate was 51%.[12]The management of intra-abdominal complications has been ill defined in all of these series. We found that anastomotic leaks and fistulae were almost managed non-operatively. The mortality associated with these multi-organ resections was not common.[6,8,12]

The survival after MVR with or without an R0 resection of the pancreas has been varied, indicating small populations and different primary cancer sites over a prolonged period. Moreover, the utilization of either neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy is often unknown. Most studies[6,7,9-12]have reported a median survival more than 20 months, assuming an R0 resection was made. In the present study, most of the patients had poorly differentiated tumors whichnegatively influence long-term survival. The degree of tumor differentiation and its impact on disease free survival in this population have been poorly defined.[7-12]And long-term treatment of patients who were subjected to pancreatic resection for locally advanced extrapancreatic carcinoma is not feasible. Thus, appropriate patient selection and counseling are particularly important for these procedures.

The use of neoadjuvant therapy prior to MVR for the pancreas has been poorly described.[7,9]Four patients in our study received pre-operative treatment in a period of 15 years, and one of them is still alive. The use of neoadjuvant therapy has expanded greatly in the recent years. Further, targeted chemotherapeutic agents and enhanced therapeutic radiation techniques have downstaged the tumor prior to surgical extirpation. Pre-operative identification of T4 tumor of the pancreas is imperative when the high-grade histology is encountered. Once identified, neoadjuvant therapy is considered the best opportunity for the improvement of disease free survival and treatment.

Contributors:BSW proposed the research project. CDR and BSW performed the research and wrote the first draft. CDR collected and analyzed the data. Both authors contributed to the design and interpretation of the study and to further drafts. BSW is the guarantor.

Funding:This manuscript was supported in part by a grant from the Kosten Foundation for pancreatic cancer care and research, Memphis, TN, USA.

Ethical approval:The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Baptist Memorial Hospital in Memphis.

Competing interest:No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

1 Mitchem JB, Hamilton N, Gao F, Hawkins WG, Linehan DC, Strasberg SM. Long-term results of resection of adenocarcinoma of the body and tail of the pancreas using radical antegrade modular pancreatosplenectomy procedure. J Am Coll Surg 2012;214:46-52.

2 Kimchi ET, Nikfarjam M, Gusani NJ, Avella DM, Staveley-O'Carroll KF. Combined pancreaticoduodenectomy and extended right hemicolectomy: outcomes and indications. HPB (Oxford) 2009;11:559-564.

3 Abu Hilal M, McPhail MJ, Zeidan BA, Jones CE, Johnson CD, Pearce NW. Aggressive multi-visceral pancreatic resections for locally advanced neuroendocrine tumours. Is it worth it? JOP 2009;10:276-279.

4 Sasson AR, Hoffman JP, Ross EA, Kagan SA, Pingpank JF, Eisenberg BL.En blocresection for locally advanced cancer of the pancreas: is it worthwhile? J Gastrointest Surg 2002;6:147-158.

5 Nikfarjam M, Sehmbey M, Kimchi ET, Gusani NJ, Shereef S, Avella DM, et al. Additional organ resection combined with pancreaticoduodenectomy does not increase postoperative morbidity and mortality. J Gastrointest Surg 2009;13:915-921.

6 Berselli M, Coppola S, Colombo C, Pennacchioli E, Fiore M, Gronchi A. Morbidity of left pancreatectomy when associated with multivisceral resection for abdominal mesenchymal neoplasms. JOP 2011;12:138-144.

7 Martin RC 2nd, Jaques DP, Brennan MF, Karpeh M. Extended local resection for advanced gastric cancer: increased survival versus increased morbidity. Ann Surg 2002;236:159-165.

8 Piso P, Bellin T, Aselmann H, Bektas H, Schlitt HJ, Klempnauer J. Results of combined gastrectomy and pancreatic resection in patients with advanced primary gastric carcinoma. Dig Surg 2002;19:281-285.

9 Pingpank JF Jr, Hoffman JP, Sigurdson ER, Ross E, Sasson AR, Eisenberg BL. Pancreatic resection for locally advanced primary and metastatic nonpancreatic neoplasms. Am Surg 2002;68:337-341.

10 Curley SA, Evans DB, Ames FC. Resection for cure of carcinoma of the colon directly invading the duodenum or pancreatic head. J Am Coll Surg 1994;179:587-592.

11 Saiura A, Yamamoto J, Ueno M, Koga R, Seki M, Kokudo N. Long-term survival in patients with locally advanced colon cancer afteren blocpancreaticoduodenectomy and colectomy. Dis Colon Rectum 2008;51:1548-1551.

12 Varker KA, Muscarella P, Wall K, Ellison C, Bloomston M. Pancreatectomy for non-pancreatic malignancies results in improved survival after R0 resection. World J Surg Oncol 2007;5:145.

13 Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg 2004;240:205-213.

14 Lin JW, Cameron JL, Yeo CJ, Riall TS, Lillemoe KD. Risk factors and outcomes in postpancreaticoduodenectomy pancreaticocutaneous fistula. J Gastrointest Surg 2004;8:951-959.

15 Yang YM, Tian XD, Zhuang Y, Wang WM, Wan YL, Huang YT. Risk factors of pancreatic leakage after pancreaticoduodenectomy. World J Gastroenterol 2005;11:2456-2461.

16 Berger AC, Howard TJ, Kennedy EP, Sauter PK, Bower-Cherry M, Dutkevitch S, et al. Does type of pancreaticojejunostomy after pancreaticoduodenectomy decrease rate of pancreatic fistula? A randomized, prospective, dual-institution trial. J Am Coll Surg 2009;208:738-749.

17 Behrman SW, Zarzaur BL. Intra-abdominal sepsis following pancreatic resection: incidence, risk factors, diagnosis, microbiology, management, and outcome. Am Surg 2008;74: 572-579.

18 Schmidt CM, Choi J, Powell ES, Yiannoutsos CT, Zyromski NJ, Nakeeb A, et al. Pancreatic fistula following pancreaticoduodenectomy: clinical predictors and patient outcomes. HPB Surg 2009;2009:404520.

19 Paulus EM, Zarzaur BL, Behrman SW. Routine peritoneal drainage of the surgical bed after elective distal pancreatectomy: is it necessary? Am J Surg 2012;204:422-427.

Received September 27, 2013

Accepted after revision December 9, 2013

Author Affiliations: Department of Surgery, University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, TN 38163, USA (Cullinan DR and Behrman SW)

Stephen W Behrman, MD, Professor of Surgery, Department of Surgery, University of Tennessee Health Science Center at Memphis, 910 Madison Avenue, Suite 208, Memphis, TN 38163, USA (Tel: 901-448-3234; Fax: 901-448-7306; Email: sbehrman@uthsc.edu)

© 2014, Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. All rights reserved.

10.1016/S1499-3872(14)60031-X

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International2014年2期

Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International2014年2期

- Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International的其它文章

- Pancreatic fistula after central pancreatectomy: case series and review of the literature

- Effects of plasma exchange combined with continuous renal replacement therapy on acute fatty liver of pregnancy

- FBW7 increases chemosensitivity in hepatocellular carcinoma cells through suppression of epithelialmesenchymal transition

- Pancreatic head cancer in patients with chronic pancreatitis

- Instrumental detection of cystic duct stones during laparoscopic cholecystectomy

- Improved anterior hepatic transection for isolated hepatocellular carcinoma in the caudate