Made in China

The name Wang Shenglin has recently become known as a creator in the whirling DIY scene taking root in Beijing’s Zhongguancun, sometimes referred to as China’s Silicon Valley.

Born in 1988, Wang graduated from Beijingbased Renmin University of China’s Business School in 2011. Instead of finding a job related to his major, he started his own business with a group of tech enthusiasts, making digital gadgets.

The whole business started in a 20-squaremeter room. “It was not intended to be a real business at the very beginning,” Wang said. “It was just for fun. Some people go to the gym. Others go to nightclubs. We built a creative community for nerds.”

playing big

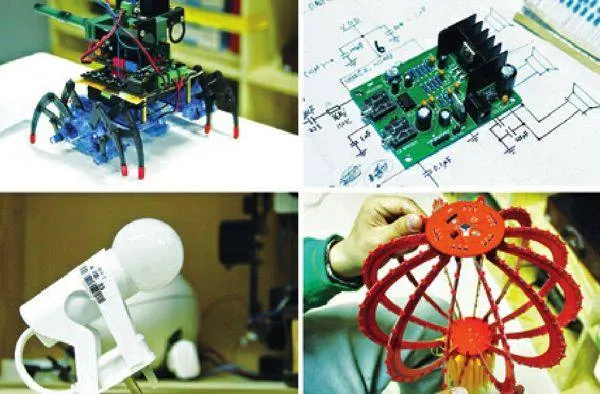

Every week, Wang, together with co-founder Xiao Wenpeng, a programmer and hardware enthusiast, held seminars with friends who shared the interests in technology, design and art. Together they made various toys by hand including a cube robot, a quad-copter, as well as their own 3D printer—a device that is capable of “printing” tangible objects from plans by melting and forming plastic thread.

“The idea of starting collectives such as this one is to encourage social innovation and develop an open-source hardware ecosystem. This can be done through building physical and online communities where people can learn, share and work on projects through interactive design,” said Wang, who named the workshop Makerspace. Wang explained that the word “maker” refers to do-ityourself enthusiasts who come to the workshop to make their own ideas into something tangible.

It’s more like a frat house for young, modern scientists. “Some call us nerds or geeks,” Wang said.“We have creative ideas and courage to put them into practice. They can be as simple as tie-dyed fabrics or as complicated as a 3D camera.”

Neither Wang nor his partners initially expected economic returns from Makerspace until the 3D printer they developed found buyers and made some money. This gave them a positive sign—ideas cannot only be changed into practice, but also into money.

Unfortunately, the 3D printer is the exception amongst almost all the experiments they conducted at Makerspace. A successful product always requires a large number of prototypes and tests that cost money and time, but Makerspace is centered around the emerging“rapid prototyping” trend where the focus is on making small one-time batches of something that is not commercially feasible. Sometimes, several months of development and testing may still result in failure.

Therefore, Wang had to look for investors to keep the workshop running. Makerspace’s turning point was in 2012 when it was awarded the title of Innovation Incubator by the Administrative Committee of the Zhongguancun Science Park, and moved to an office of about 200 square meters in the Zhongguancun International Digital Design Center in Haidian District.

The new larger space allows their sharing sessions and lectures to attract dozens or even hundreds of members to attend.

In May 2012, Makerspace held the Beijing Maker Carnival in conjunction with Beijing Design Week. The projects on display ranged from a pen that draws automatically, to a wig that plays music according to how hard the wearer shakes his or her head.

The workshop has collaborated with the Ullens Center for Contemporary Art since the beginning of 2013 by holding seminars there once a month, providing opportunities for more people to enjoy the DIY revolution.

“We basically attract people who are interested in making things,” said Melva Lai, a 23-yearold employee at Makerspace. “You can call them inventors. Some of them didn’t make things before or they only had experience at school making projects.”

Meng Qi, a do-it-yourselfer at Makerspace, however, doesn’t quite agree with the definition of “inventor.” With a punkish hairstyle and tattoo of a passage of Taoist scripture on his right arm, the 28-year-old is crazy for making music with his homemade synthesizers. “I didn’t invent it, I designed it, or redesigned it,” he said.

Meng, with only a high-school education, now works as an instructor at the Beijing Contemporary Music Academy and specializes in synthesizers. His knowledge of electronic engineering is entirely selftaught.

Meng’s cluttered apartment is covered with touch-sensitive planes and colored plugs. He made some instruments at home, including an optical theremin, which changes its pitch based on the brightness of the light shining on it and reacts best when played with a flashlight.

“It is hard to make a living by selling these homemade instruments,” Meng said. “You need to buy a lot of components that you may not need later.”

Continuing traditions

“The concept of do-it-yourself is not new in China at all,” Wang said.

Years before Wang’s Makerspace, China had seen a group of such tech enthusiasts from different walks of life. Wu Yulu, a farmer from Mawu Village in east Beijing’s Tongzhou District, started making robots in 1986.

Wu has only elementary-school education but found himself fascinated by machinery and mechanical engineering. Now Wu has made more than 60 robots, some of which can pull carts, climb walls, write words and even serve tea. Some of them are on display all over the world, including Britain and Brazil. In 2010, Wu’s robots participated in the opening ceremony of the World Expo in Shanghai.

“Initially I didn’t have any intention of making a useful robot,” Wu said. “I just found a feeling of accomplishment from having an idea and making it into something real.”

The BBC featured Wu in a documentary in 2007, and he has been invited to give seminars on mechanics to college professors and students occasionally.

Tao Xiangli, a 35-year-old farmer from east China’s Anhui Province, who also only finished elementary school, built his own submarine on the outer edges of Beijing.

“People like Wu and Tao can best define the spirit of Makerspace—as long as you have an idea, you should make it come true,” Wang said.

Wu believes that emerging workshops like Makerspace will encourage creative development in China, since they bring people of similar interests together. There are more than 1,000 similar collectives around the world, according to Wang, and China has five in such cities as Beijing, Shanghai and Shenzhen in Guangdong Province.

“I think China has great potential for cultivating more creators and it will become a paradise for such people as the country supplies almost all the cheap electric components and we see more and more young people having great passion in this field,” Wang said. “What we are doing now is telling people, especially the young ones, that science is not mysterious or high up at all, it is something that everybody can engage in easily.”

“It is an open community lab, where people gather together to share resources and knowledge to build and make things,” said Wang Chunyan, a professor at the Central Academy of Fine Arts’ design lab. “The American sitcom The Big Bang Theory exemplifies best who we are. Perhaps we all want to explore the complexities of being a nerd.”