COMPLEX ISSU

India’s recent announcement to develop unilaterally and independently the disputed China-India border region without loans from the Asian Development Bank once again spurred public concern over the Sino-Indian border disputes following the “tent confrontation” incident between the two armies this April. The region, which China calls Zangnan (South Tibet) and India calls Arunachal Pradesh, is currently under Indian control. It is undeniable that overheated media reports on Sino-Indian border disputes in recent years are partly exploited to attract attention, but it also shows that the border dispute is one of the most sensitive issues in terms of Sino-Indian relations.

Although a final settlement over the border issue cannot be immediately achieved, both sides share a similar willingness to resolve the dispute as their stances gradually converge. The key to resolving the issue completely is to enhance mutual political trust.

Creeping progress

The Sino-Indian border dispute is a complicated historical issue. The two countries have lived in peace with each other in spite of no official boundary in the contested area. However, it is not a coincidence that the border issue became a major barrier impacting bilateral relations over the past six decades.

Historically, the two countries have formed a traditional borderline in the east based on the traditional living habits of the two peoples and the boundary of administrative jurisdiction of each country. For over 2,000 years, the two peoples have respected this fixed borderline and developed a kind of permeable relationship. However, starting with British colonial rule in South Asia, the British Empire sought to expand the borders of its colony of British India to surrounding countries. British colonists also illegally signed a Simla Accord with China’s Tibetan local government and set the so-called McMahon Line to define the China-India eastern border. Following independence, India inherited the British colonial legacy and advanced its borderline with China to the McMahon Line in the 1950s. In the meantime, India also put forward its territorial claim in the western part of the China-India border. After the China-India border war in 1962, the two countries formed the current line of control in their respective borders.

The settlement of bilateral border disputes has been always a top priority of bilateral relations. Since the two countries began border talks in 1981, the two sides have successively established vice-ministerial level talks, joint working group talks, China-India border issue diplomats and military experts’ panel meetings, special representatives meetings as well as the Working Mechanism for Consultation and Coordination on India-China Border Affairs. These platforms have made gradual progress. In 1993, China and India signed the Maintenance of Peace and Tranquility along the Line of Actual Control in the India-China Border Areas; and later in 1996, the two sides signed the Confidence Building Measures in the Military Field along the Line of Actual Control in the India-China Border Areas. The two pacts allowed both sides to lay a solid foundation for maintaining long-term peace and security in the disputed area.

Special representatives were also appointed with the political mandate to steer negotiations in 2003, discussing the framework on settling the border issue. The first round of the special representative meeting established a three-step development strategy over the border dispute settlement: making the guiding principle, and then setting up a framework agreement to implement the guiding principle and setting the borderline at last. During the fifth round of special representative talks in 2005, the two sides finally reached the Agreement on the Political Parameters and Guiding Principles for the Settlement of the Boundary Question. Though no consensus has been reached over the framework, the objective of the second stage is very obvious for the two sides—that is, setting up the framework as soon as possible.

During Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao’s official visit to India in December 2010, the two sides reached consensus and signed an agreement on the Working Mechanism for Consultation and Coordination on India-China Border Affairs. It mainly provides channels for communication and exchange between the two sides and ensures the peace and stability of the disputed area to create good conditions for a final border dispute settlement.

The two sides have formed an overall roadmap for dispute resolution. First, the two countries established the principle of settling the disputes through peaceful means; second, the two reached consensus that they should resolve their differences over the issue in a fair, reasonable and mutually acceptable way; third, they set a three-step strategy with high operability; fourth, they made up the principle of resolving the problem eventually as a package rather than step by step; and last, the two agreed to guarantee peace and stability on the border to create a good atmosphere for the final resolution of the issue.

Mutual trust needed

Objectively speaking, India’s enhancement of its defensive strength in the border region is understandable and undisputable. However,some Indian media and analysts and the Indian military frequently use the “China threat” as an excuse for India’s military build-up. This shows that the mutual trust between China and India is insufficient. A recent survey shows that 9.5 percent of China reports in the Indian media are negative, 4.2 percent are positive, and the rest are neutral, among which the so-called Chinese army “invasion” of India is the most frequently reported topic. In comparison, negative reports are more likely to occupy the front pages. But in China, 16.2 percent of India reports in the Chinese media are positive and only 1 percent is negative.

The border dispute between the two countries is undoubtedly the major cause of the low mutual trust, while the development gap between the two countries also leads to anxiety on the Indian side.

In a recent China-India media exchange program held in Beijing co-hosted by the Global Times Foundation and the India-based Observer Research Foundation (ORF), Chilamkuri Raja Mohan, renowned Indian columnist for the Indian Express and expert on strategic research at ORF, made a comprehensive conclusion about the bilateral mutual trust insufficiency from the perspective of the Indian side. He said that Indian media and people are always expressing five “sentiments” about China—India admires China’s rapid rise; both countries have an important influence over Asia and the world; India is trying to learn from China’s economic growth; Indian people are yearning for more opportunities in China; and India is scared of China’s rise, especially its swelling military strength. In the last 25 years, the increasing exchanges between India and China, as the first four sentiments indicate, have brought back to life a lot of unresolved issues, such as border issues, which led to the fifth sentiment.

It is not so worrying that there are differences, competition and even conflict between the two countries. The key problem is how the two sides try to enhance mutual understanding and create a cooperative atmosphere with trust. The proper settlement of the “tent confrontation” incident of the two armies reflects that the militaries and foreign affairs departments of the two countries are able to have close and timely communication with each other through the established working channels to deal with the problems. It also shows the two countries have the wisdom and capacity to continually develop the bilateral cooperative and friendly relationship while managing existing divergences.

Nevertheless, we should not deny that the military exchange between China and India is far from that of India with other countries, including the United States. The bilateral military relationship should be further expanded. Fortunately, the bilateral high-level military exchange which was suspended in August 2010 has been resumed in 2011 and will continue again this year. It is a positive signal. But the development of India’s national defense should not be based on hyping the China threat, which could only fan the flames of nationalism and destroy an already fragile political mutual trust.

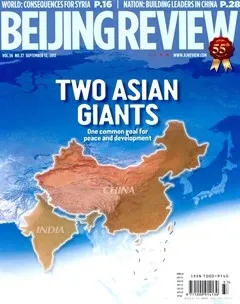

China and India are neighbors as well as the world’s two largest developing countries. The successive rise of the two countries has become the most significant event in the AsiaPacific region and the Indian Ocean region. The two have become the major driving forces for the future development of the world economy. Their development also promoted the gradual integration of the Asia-Pacific region. But the insufficient mutual political trust caused by the half-century long border dispute is still the major obstacle of bilateral relations. Under the context of the U.S. rebalancing strategy, the development environment of China and India is also changing. It adds complexity to the variation of the fbHhQ/mUoQAzxRlGQa9B48Q==uture regional pattern of the PacificIndian Ocean region together with the border dispute-affected ChinabHhQ/mUoQAzxRlGQa9B48Q==-Indian relationship. As long as both China and India follow the threestep roadmap for settling the border dispute and give full consideration to historical factors, a final settlement on the China-India border dispute is no doubt possible.