合作的意向文化

作者:艾莉森·门登霍尔

“DesignWorkshop的学术底蕴会继续推动公司占据研究型实践的前沿。我相信,许多中国设计公司和机构都会因DesignWorkshop对该使命的持久坚持以及致力于终生学习的精神而深受鼓舞。”

–景观建筑教育者理事会研究副会长李明翰

设计工坊

无论是初次参观DesignWorkshop的访客还是DesignWorkshop的长期员工,走进六个公司办公室中的任何一个,就会立即感受到工作室的创新性以及交谈的活力。合作气氛和目标意识在这里是十分明显的。

一个工作日的典型场景是,项目团队聚集在开放的工作室,对固定在墙上的设计图进行考量,设计师们则专心地沉浸于铺展在大号设计桌上的图纸。在会议室里,设计团队正在向客户汇报,并与其他顾问一同主持战略会议。他们探讨的焦点有可能是度假区规划、社区规划、街道景观或公园设计。当设计团队聚集在一起评论并改进他们作品的时候,激烈的讨论贯穿于整个工作室。团队的每一个人,从负责人到实习生,都被期待对讨论有所贡献。这就是DesignWorkshop的文化实景。

合作文化

刻在门上的名称DesignWorkshop对于员工解决复杂的设计问题以及在实体空间中完成工作都具有重要意义。(参看图1)热烈的并且有意向的文化即将来临。所有DesignWorkshop分公司的共同特点是拥有高层高、大公共桌以及充足的展示设计及草案的围墙空间,在这样的公司环境中,一件件的设计作品被反复创造。所有项目组都需要对自己的设计进行审查,而且要展示给组外的同事。大家在时而亲切时而热烈的气氛中分享建设性批判意见,但共同的目标是完善设计。设计讨论发生在办公室的“公共空间”,这样迫使员工离开自己的办公桌,摒除设计“盲点”,否则,这些设计“盲点”可能会使员工无法看到所有可能的解决方案。当然,员工也会在自己的办公桌工作,在绘图桌上画图或者在电脑上建模。但是,DesignWorkshop的文化以及强调合作的价值观要求各项工作都是可视化的——无论是固定在墙上、大图打印、还是投影,以便团队的每一个人都能看到——从而鼓励大家进行批判性的对话,这对推动项目设计进入项目决议是必须的。(参看图2)

城市观察员简·雅各布斯在《美国大城市的死与生》(1993年)探讨了“混合”产生的活力,而“混合”发生在多元化使用与城市居民在一天中不同时段于街道和公共空间活动相聚集的时候。雅各布斯把热闹城市人行道的复杂秩序比作“精巧复杂的芭蕾舞剧,每个舞者和乐团都特色鲜明,奇迹般地相互为用,构成了一个有序的整体。”DesignWorkshop强调以开放式的工作室作为创造和发明的空间,让团队成员聚在一起共同交流,以开发出新的设计,这样的做法正是借鉴了上述的想法。团队成员及其技能和经验都聚集在工作室内,相得益彰。

史蒂文·约翰逊在《涌现:蚂蚁、人脑、城市与软件的生命连结》(2001)中探讨了“集体智能”的现象,从一个蚁群的例子开始,蚁群通常被误认为是由发行指令的一只蚁后统治的。而事实上,蚁群是集体做决定的,共同使群居生活协调发展。通过随机相聚,每只蚂蚁都敏锐地关注彼此的动作与行为。从相互交流中所产生的是一种自我组织系统,它能解决蚁群内更大的问题。约翰逊还把城市视为自然发生系统。与雅各布斯一样,他也着迷于人行道,它“把随机排列的大量个体混合在一起”,并且促进当地互动和信息交流,而这些信息在城市尺度上会汇集成“复杂秩序”。DesignWorkshop实践的关注点是场所营造——公司外所实现的迷人公共空间设计——已被应用于产生设计的工作室。这就是公司的公共空间,它让设计团队集中在一起相互交流和解决问题。这是DesignWorkshop自身概念的核心,它能促进团队合作,有助于处理复杂项目。

目前有许多公司都在探索如何创造可以鼓励互动和创新的工作环境。国际设计公司IDEO的共同工作空间是经常被提及的例子,同样被提到的还有硅谷的企业园区中的皮克斯动画工作室和Facebook。试图阐明通力协作的价值以及促使其成功的背景和条件的文章和商业书籍也正泛滥成灾。乔恩·R·卡岑巴赫和道格拉斯·K·史密斯在《团队智慧:建立高绩效组织》(2006年)一书中对组织研究团队、生产和构思的公司进行了描述,并探讨其他许多组织忽视群组努力的潜能或致使其效率低下的原因。同样,《塞氏企业传奇——最不同寻常的成功企业的故事》(1993年)讲述了巴西公司塞氏企业的故事,塞氏企业是里卡多·塞姆勒的家族企业,它通过非正式的实践对机构进行变革,在提高创新力和生产力的同时,也改变了现有的公司文化。

成立四十多年以来,早在最近许多探索如何优化企业工作场所的书籍和机构出现之前,DesignWorkshop就已拥有最佳合作环境的强烈观念。在中心开放式工作室以外的区域是个人的工作空间,而角落办公室是不存在的。相反,不同资历的员工分散在不分等级的各个办公桌。在这一场景中,交谈可以被听到,信息也可以在所有的员工中高效传播。与设计负责人的近距离接触(和亲近)对于经验较少的员工来说是有启迪意义的,员工与不同角色、知识和专业技术相融合可以强化办公室工作氛围的合作性。

合作在DesignWorkshop意味着许多事情。既可以意味着与坐在数张办公桌远的人并排工作,也可以意味着与其它州或国家的同事共享文件和工作成果。某些项目团队是由来自于DesignWorkshop六个办事处的员工组成的,视特定专业技术需求或者在最后期限内人员是否有空而定。通过音频、网络和视频会议系统,就有可能实现办事处之间以及与客户之间的合作。技术可以使设计对话超越各个办事处之间的以及与全球客户之间的距离,使不同办事处成员组成的团队能够完成工作。它能确保办事处之间能够很容易地联系到彼此,避免相互隔离,而这种隔离正是许多有多个办公地点的公司的弊端。

DesignWorkshop的管理结构是对企业普遍存在的等级制度的公然挑战。员工持股计划使员工享有公司的所有权权益,并且使人人有功于公司成功的心态得以强化。公司的每月结算与收入预测对每一个人都是共享的,这些人包括从电话接线员到高级职员。办公室记分卡描绘了每个办公室的健康情况,不仅显示了营业收入、积压代办的事务和资源运用等财政状况,而且显示设计审查以及最近获奖的数量,这些是设计迭代、卓越和办公室可视化的指标。这种理念和不寻常的透明度是以《伟大的商业游戏:释放能量与账目共享管理的盈利性》(1994年)所论及的观点为基础,这本书推广账目共享的管理方法,员工获得信息授权,有归属感和经营业绩的责任感。DesignWorkshop的员工都具有创业的态度,公司多年来扩展到不同的区域,可以明显感受到灌输这种精神所创造的价值观。例如,为客户提供市场分析和战略发展规划的高尔夫球场设计与开发服务都是DesignWorkshop的员工推出的,他们都是出自对专业咨询领域的酷爱和兴趣,并且证明了把公司的服务扩展到这些领域的财务可行性。

产生于学术界

DesignWorkshop的名称以及该公司的经营方式来源于其创办人在创办设计公司之前作为专业学者所获得的经验。20世纪60年代末在北卡罗来纳州立大学教学期间,乔·波特和丹·恩赛因认为有必要在学术与专业学科合作遭到破坏和扼杀的领域展开工作。1969年,他们与来自于不同学科部门的其他两名教授一起开放其实践,目的是创办一个“研讨会”,让整个大学的教育工作者、业内人士及学生之间能够合作无间。该公司被命名为“DesignWorkshop”,意在描述一种合作文化。

虽然现在乔·波特从公司退休了,但是,与公司成立之初一样,他仍然拥有与创建DesignWorkshop之初相同的美好意愿。最近在回顾公司的起源时,波特指出,“我们的粮仓建立于商业、法律、设计、建筑、景观建筑、工程、财务和其它学科以及创造建成环境和维持生态系统的特殊兴趣中。这些筒仓生于长于学术界,而在学术界,受到奖赏的学者往往以牺牲合作和学科联系为代价专攻某一学科并越走越深。基于研讨会的概念组建公司,是为了尝试让不同行业的人为了共同的目标而在一起工作。处理复杂的规划与设计问题需要来自于不同学科的思考者。使其合作的方法是把设计工作建立在共享的价值观和原则的基础之上。”(参看图3)

基于原则的实践

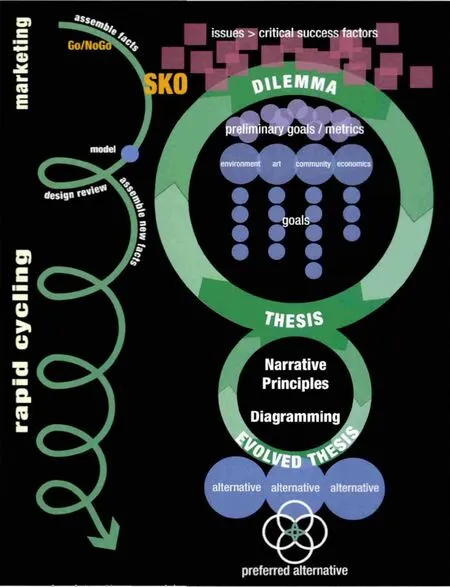

DesignWorkshop的实践是由四项原则界定的——综合性、包容性、透明化和知识——这对合作和严谨设计方案都是必要的。第一项原则综合性最好用图形来表示:(参看图4)

通过可持续发展四个必不可少的领域——环境、社区、经济和艺术,可实现产生设计方案的原则。这些关键领域构成了该公司的DWLegacyDesign®方法的连环锁。每一个项目都代表着平衡这四领域目标的机会,以完成为对环境敏锐的、支持社区的、经济可持续发展的以及可产生艺术效果的项目。由于DesignWorkshop承接的项目具有一定的复杂性,因此需要一种四重盈余法才能真正实现可持续发展。第二个原则包容性明确了DesignWorkshop产生设计理念的方法。场所营造的业务包括广泛征求设计团队、咨询专家以及客户与社区的意见。

第三个原则决策过程透明化体现在工作室的环境以及与群体互动以推进工作所展现的公开性。展示项目目标和决策依据有益于所有的参与者,使团队更具凝聚力。

第四项原则是知识。DesignWorkshop非常重视基于项目的研究,从而带来知识发展和设计创新。评估项目的绩效,使团队能够检验设计策略、扩展专业知识并确定是否有可能进一步创新。

正规的设计方法

自成立以来,DesignWorksho p的指导思想一直是与综合性、包容性、决策过程透明化和知识有关的以过程为导向的理念。但是20世纪90年代,公司的领导层决定在股东内部使这种基于原则的设计方法正规化。为了以真正合作的方式进行经营,作为研讨会的参与者,设计团队必须遵循一种共享的方法论。DWLegacyDesign®的方法是对综合性、透明化、严谨和迭代过程的概括。公司由此制定出方法图表,作为员工的设计路径图。(参看图5)

该图表描述的是如何利用战略性会议启动每一个项目,从而为团队开展工作以及吸引客户和股东奠定基础。在会议过程中,团队着手调查了解项目面临的机遇和挑战,并进行综合调查为项目相关研究提供信息和确立绩效目标。按照学术实践,团队为每一个新项目制定了一份项目挑战声明(称之为“项目困境”)和假设声明(称之为“项目主题”)。在团队的集体努力下,“项目困境”使团队产生凝聚力,绕开障碍,从而成功获得设计方案。“项目主题”设定了最终设计的愿景,也时刻提醒团队所要追求的结果。

每个项目启动时举行的气氛热烈的会议确定了项目目标,而这个目标平衡了经济问题、社区价值、环保问题和设计艺术,使其成为凝聚的愿景。有了目标,就有了研究任务,团队成员被安排钻研与项目有关的议题。做进一步探究,可以使团队能够预测完成项目的量化绩效利益。对设计发现、合作和责任性这一初始过程做出概括,可为团队提供路径,对项目的成功是至关重要。

快速循环

DWLegacyDesign®的核心元素是快速循环的概念,用方法图表左侧上的环线表示。快速循环属于迭代过程,是公司的设计实践的核心。设计不是线性的运动项目;而是会演化的。DesignWorkshop的项目是复杂的并且位于特定场地的。设计产生于可控的周期内,而可控周期是由控制、巩固和向客户提交工作并反馈意见时产生的一系列情感宣泄的探索的集合。DW的董事会主席库尔特·卡伯特森补充指出,“快速循环也能够被视为两种思维模式之间的碰撞过程——创造性思维和批判性思维。图表里的环形描述的是我们作为设计师经历的过程——先尝试做一些事情,从中学习一些东西,再尝试做其它的事情,以便从中学习一些新的东西。”这种在专业实践过程中试验性的模式被M.I.T.社会科学家唐纳德·A·斯肯称为“在行动中反思”,这位科学家在设计过程中识别出三种对于严格迭代的独特方法:探索、移动检验和假设检验。在DesignWorkshop,项目经历的周期数取决于其空间大小、进度和费用以及团队对设计质量和完成程度的评估。以这种方式处理设计,只要在图表上标注,就逐渐向员工灌输了迭代的重要性。设计团队被希冀可以在一定时期内专心工作,同时也可以定期停下来接受外界的观点。设计如何演化和进步是公司合作文化的关键。

进行设计审查是团队征求客观反馈意见以便为设计提供信息的一种方式,这是工作室的重要基础,也是公司环境是否健康的最终检验。设计审查有许多不同的形式。有些设计审查是在项目例会上进行的,会议上的对话仅限于想要对设计进展进行更新的团队成员之间。其它设计审查发生在个人办公桌旁,这时也许一名正出访的负责人想要对项目进度进行检验。但是,研讨会的核心是在办公室或公司范围内召集进行的设计审查,目的是广泛征求客观性批判意见。在此情况下,整个办公室会在午餐时间聚在一起听取团队的简短报告。披萨饼是参会的酬劳。举行设计审查有多个目的:寻求设计反馈意见、分享客户对最近汇报的反应并指明下一步的方向、准备新项目的访谈,以及/或者对奖项提交的草案进行分享。这样的设计审查是带有批判性思维的深思熟虑过程的一部分,旨在为进一步的创新研究做好准备。(参看图6)

知识的形成

DesignWorkshop的员工通常会讨论参与批判性实践的意义。在这一点上,他们认为应该关注那些影响到即使不是地球和全人类也至少是建成环境的全球性议题。公司用幻灯片按季度进行情况介绍,欢迎新员工加入,其中就包括2007年的《新闻周刊》封面,该封面突出的是一个地球仪,并把描述政治、古生物学、金融、艺术、通俗文化、科学等内容的图像网格映射在地球仪的格网上。标题为“你需要立刻知道的181件事”。与新员工分享这一图像的目的是向他们灌输超越某个特定项目的范围和实际界限看问题的重要性,并且使他们关注总体建成环境和具体项目场地的广泛影响因素。综合型DWLegacyDesign®方法的核心是强调高额的调查研究与多意信息的综合处理。

DesignWorkshop项目团队时常寻求了解各种主题,并将其融入设计,而这或许在上一代被认为已超出传统景观建筑实践的范围或能力。公司项目的复杂性迫使其团队拥有大量的信息和工具,以便进行设计和对成功进行评估。除了关注实体空间设计和形式创造之外,一个典型的团队可能会计算总体规划社区的职住比,以求减少发展产生的车行次数或路程。他们可能会关注社会公正的问题,或者利用有针对性的调查确保项目的社区参与策略考虑到了受影响的部分人口。抑或,他们可能会研究某个区域的零售空缺或交通事故率,以便了解和衡量在实施街景改造前后的影响。批判性实践需要智慧性运营,并且需要对影响建成环境的广泛议题保持高度注意。

由于承认项目的复杂性,DesignWorkshop不仅着手努力收集有助于设计决策的信息用来指导公司的最佳实践,而且还开展正规的研究,以创造行业的新知识。作为这项工作的一部分,项目团队在设计中以及实施后越来越多地使用循证设计来衡量项目的绩效。紧接着新项目合同的签订,任务团队会聚集在一起,寻找出会影响设计和实施结果的各种相关因素和机遇。研究清单和指标议题会被进行审查和优先考虑。在这次初始会话中围绕着小组的关键问题是,“我们和我们的客户对于这个项目想要讲述什么故事?”在设计工作开始之前问一下这个问题并想象一下最后的结果,有助于构建该项目的议程。该会话会产生一个综合性大纲,各种因素和机遇则变成是与环境、社区、经济或艺术有关的研究主题和目标,它们会分配给团队的不同成员。(参看图7)

在整个设计过程中,项目团队会针对已设定的目标对设计进行评估。在起初设定的可衡量目标是评估项目过程中备选设计方案的一种工具。在这个阶段,设计尚未实现,因此仅可显示出成功的迹象。直到在设计实施后进行绩效评估,才能产生成功的证据。很少设计公司有能力自己承接这一工作,这就是DesignWorkshop积极参与景观建筑基金会(LAF)的“景观绩效系列案例研究倡议(CSI)”的原因。这一计划使实践者与学术团队相合作,而学术团队开展的严谨研究可对建成项目交付的可持续景观绩效利益做出衡量。正如DesignWorkshop在过去三年里与犹他州立大学合作,这种合作可确保对项目进行客观研究,并且可以使用科学方法对各种主张进行验证。这些研究已发布在LAF网站上(见侧栏),作为行业提高其可持续发展实践水平的资源。此外,学术团队也在同行评议的出版物发表研究,并在各项会议上展示,如:景观建筑教育者理事会(CELA)。

知识必须在项目背景下形成并在项目团队中进行交流,对这种期望必不可少的是DesignWorkshop门户,这是分享整个公司的知识和信息的内部网站。每个人都可以看到在该门户公布的一系列信息,从员工结婚通告到办公室联谊会,从公众会议召开的最佳实践到不透水表面减少的新方法。其中大部分信息都在内部网站的主题页面上,每个页面都有一个DWLegacyDesign®的指标议题。从城市热岛效应到植物技术再到生态排水沟,这些在线网页收集了公司内外部的信息,包括基准目标的范例、设计策略、在线计算器以及与各组织机构的链接,其中这些组织机构在主题、文章、白皮书和示范项目多方面各有所长。该门户还为全公司的社区实践提供了一个家园,它把拥有共同设计兴趣的员工聚集在一起,也把在某一特殊领域主管提升公司能力的职员聚集起来,这些特殊领域诸如:数字化表现或绿色屋顶设计。要在DesignWorkshop工作,必须成为网络化社区的成员,这个社区重视知识,每一个人都有望为知识的扩展作出贡献。

持续学习

DesignWorkshop极力强调持续学习,这既是为了员工的专业发展,也是为了把新思路和专业知识注入到每一个项目中。希望员工提升专业知识并与同事分享以促进实践,这是公司基于学术的构成方式。这种注重学习的方式不仅体现在全公司的正规计划上,也体现在各个项目内容中。

DesignWorkshop的员工“五年计划”描绘了员工在公司前五年被赋予的期望,这些期望包括增长知识以及确立成功的、令人满意的职业生涯凭证。该计划明确了建立基本技能、展示思想领导力、攻读研究生课程及获得专业许可和认证的目标和时间线。必须有研究生学历才能晋升到领导职位。公司深信,攻读研究生学位是一种转型经历,可以增强自信心、提升智能和个人成熟度、提高专业能力。员工出席会议并发表文章也是受到鼓励的。“五年计划”的目标旨在描绘一种使青年才俊有计划的尽快发展而不是任其随机努力的过程。DesignWorkshop强调知识的发展和共享,也强调通过认证和学位巩固知识,力求促使员工尽快从新手发展成大师。一年两次的绩效评议是使每个员工能够针对专业发展目标衡量其进步的里程碑。

公司每年都会计划举行一系列内部员工和特邀专家的午餐时间报告会。一个月举行数次的“午餐学习会”针对与设计、特定项目类型或一般技能培训相关的主题进行简短的报告。各个办公室的员工都会连接到网络会议听取报告,并在每个讲座总结时参与讨论。最近的主题包括雨洪管理、城市行道树、植物修复、公共艺术、数字建模、会议简易化、项目管理和GIS。

自2006年以来,DesignWorkshop已针对各个主题或项目类型召开了10多次全公司座谈会,其中有许多是公司重点关注的领域,包括城市廊道设计、种植设计、新社区开发、公园设计和社区综合规划。当几个DesignWorkshop办公室在做同一类型的项目时,就会召开会议,使团队能够分享最佳实践。外部的嘉宾也会被邀请作为主题演讲者,并确立讨论框架。处理相似问题的数个项目团队会应邀参与简短的报告会分享最佳实践和接收反馈意见。虽然参与座谈会会损失员工赶工期的紧迫感,也会消耗员工一天中的部分带薪时间,但是公司领导层认为,这些会议可扩展行业最佳实践的意识、提升项目设计并加强所有办公室之间的联系。这些会议强化了“研讨会”的概念。

公司确信,使员工与知识相联系,并教会他们如何进行项目相关的研究将有利于实践进步,这种信念已经使旅程和探索超越了DW六个办事的局限。从2005年至2007年,整个公司都会到美国的不同城市进行年度休假会议。2005年内华达拉斯维加斯集会的重点是设计方法。2006年,员工到访俄勒冈州波特兰,其重点是关于环境和艺术,这两者构成了DWLegacyDesign®的主要范畴。社区和经济是2007年伊利诺伊州芝加哥会议的重点。这些类似会议的聚集举办讲座、分组座谈会,也可以参观示范城市项目,会议由内部专家和发言嘉宾担任主持,对到访城市的建成环境所取得的综合性可持续发展实践提出特别的见解。(参看图8)

“在DesignWorkshop工作就像是回到学校一样,”乔什·布鲁克斯说道。他毕业于巴吞鲁日路易斯安那州立大学的罗伯特·赖希景观建筑学院,取得学士学位后新近加入公司。“我真的很欣赏贯穿整个年度的所有学习活动。频繁举行的设计审查为工作室注入了探索意识和批判意识,为设计探索奠定了基调。”

与学术界的联系

作为一家学术界出身的公司,DesignWorkshop与美国各大高校的设计计划以及全国范围内的教授都维持着密切的联系。犹他州立大学的景观建筑计划已被指定为公司档案室的接收者。数年来,公司创建了一项“驻院老师”计划,邀请教授在休假日或暑假在公司的一个或所有办事处里工作。这些安排产生了巨大的相互利益。对于学者而言,他们可以利用这个机会参与专业实践,并利用这些时间把研究运用于即将实施的项目。而与教员的互动,使员工有机会直接向在某一特定领域有着丰富知识的专家学习。由于DesignWorkshop拥有以过程为导向的设计实践以及为了追求设计方案而共享的方法论,学术到访者在工作室往往有一种宾至如归的感觉。乔治亚州立大学环境设计学院景观建筑系的富兰克林教授兼美国雨洪设计和技术专家布鲁斯·弗格森已在DesignWorkshop工作了两个夏天,波尔州立大学景观建筑教授莱斯·史密斯也在其休假期间花了数个月的时间在DesignWorkshop,对艺术创作与设计之间的交叉点进行强化。(参看图9)

DesignWorkshop赞助两项缩小学术界与专业实践的距离的计划。第一项计划是“设计周”,期间,负责人及数名员工会与一系列高校名单中的景观建筑或规划本科课程的老师合作,举行一场为期一周的专家研讨会,重点是讨论特定场所的设计问题。给学生讲授如何开展综合性设计过程之后,会创建跨学科团队重点解决复杂的设计问题。在志愿者活动时间,与学生互动并教会他们如何开展严谨的专业实践对公司的员工而言是很鼓舞人心的,这也使我们与教职工和学术机构建立了新的联系。学者和学生都会接触到公司公布的研讨会方法以及由于跨学科的努力带来的累累硕果。迄今为止,公司已在数个享有声望的设计学院举行了“设计周”,包括克莱姆森大学、肯塔基州立大学、路易斯安那州立大学、德州农工大学和宾夕法尼亚州立大学。(参看图10)

此外,DesignWorkshop还赞助一项年度暑期实习计划。公司在六个办事处内总共征集约12个实习申请。每一年,在暑期的第一个星期,其中一个办事处会被指定主持由所有实习生参加的高强度的多天设计研讨会。学生沉浸在公司的合作文化中,并学习DWLegacyDesign®方法的过程。然后,每一名学生会被分配到DesignWorkshop的其中一个办事处,把暑期剩余的时间花在客户委托的公司项目上。(参看图11)

合作的意向文化

DesignWorkshop的名称、实体空间、综合性设计理念、合作设计原则以及共享的方法论不断强化着“研讨会”的概念。公司的每一个人都有责任秉承合作文化。

每一名员工都是研讨会的主体。在很大程度上,设计团队会自我组织并发起会话,从而在以发现为导向的环境中提升理念。不过,必须培养合作文化。为了提升研讨会的理念并反复灌输这种实践方法,由每个办公室派出的LegacyDesign代表组成的团队每个月会集会一次,分享新的研究或者通过绩效指标评估设计和建成效果的方法。他们还会讨论每个办公室的研讨会文化情况,并根据需要采取培育措施。如果某个办公室的设计审查流程和团队合作已衰退,这些管理人员将鼓励小组改变行为方式,并且在工作室共用区域征求项目团队外人员的意见。在其它情况下,可能安排办公室之间的设计审查,以激发全公司的交流和思路分享。

简·雅各布斯写道,“没有强大、包容的生命核心,一个城市往往会变成彼此孤立的利益的收集站。它在社会、文化和经济上的产出很难大于各独立部分的总和。”丰富的系统、用途和人的重叠参与才形成了极其重要的城市空间。把这一思路运用于设计工作室,设计师的关注领域以及不同观点的传播对工作室的生存是至关重要的,因为工作室是一个知识形成和复杂设计问题解决方案生成的地方。最高设计质量的实现是依靠研讨会团队的贡献,而不是单单依靠个人的行为。在DesignWorkshop,我们每天都在有意地创造这种条件以秉承公司的文化,这是公司创办的核心,也是公司持续运营到今天的方法。

艾莉森·门登霍尔是DesignWorkshop的综合型可持续设计实践DWLegacyDesign®的总监。她开发了DesignWorkshop的景观设计、城市设计和土地规划实践的研究工具和模型,并讲授强调公司建成工程的绩效衡量的方法论知识。阿利森因其在大型、复杂的多学科设计和规划工作的项目领导能力而著称。艾莉森是哈佛大学和哈佛设计研究院(GSD)的研究生,是GSD校友理事会和景观建筑基金董事会的一员。

A Design Workshop

Whether one is a first-time visitor to Design W orkshop or a long-time Design Workshop employee, when walking into any of the firm’s six offices, there is an immediate sense of the creative energy of the design studio and the liveliness of the conversations. The collaborative atmosphere and sense of purpose are palpable.

On a typical day, project teams are gathered in the open studio space, considering designs that are pinned up on the wall and designers are leaning intently over drawings spread on large layout tables. Conference rooms are filled with design teams presenting to clients and leading strategy sessions with other consultants.Perhaps a resort or a master-planned community or a streetscape or a park is the focus. Boisterous discussions about proposed designs are heard throughout the studio as teams huddle together to critique and advance their work. Everyone on teams, from the principals-in-charge to the student interns, is expected to contribute to the conversation. This is Design Workshop’s culture in action.

Culture of Collaboration

The name on the door, Design Workshop, speaks volumes about the way staf f members conduct themselves to solve complex design problems and about the physical space in which the work is accomplished.(see f g. 1)It heralds a culture of collaboration that is intense and intentional. Designs are created and iterated in the common areas which, in all Design Workshop’s off ces, are def ned by high ceilings,large community tables, and ample wall space where plans and sketches are gathered. All project teams are expected to conduct design reviews where the work is presented to colleagues beyond the design team. Constructive critique is shared in an atmosphere – sometimes genial, sometimes heated – with the common goal of improving a design. Design discussions take place in the “public space” of the off ce to force staf f to leave their desks and discard any design “blinders” that may inhibit seeing all the possible solutions. Certainly, employees work at their own desks, drawing on drafting tables or modeling on the computer. However, the culture of Design Workshop and the value placed on collaboration require that all work be visible – pinned up on the walls, printed large or projected so everyone on the team can see it – to spur the critical conversations that are necessary to propel project designs into project resolutions. (see f g. 2)

In The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1993), urban observer Jane Jacobs discusses the vibrancy created by the “mingling” that takes place when there is a convergence of diverse uses and urban dwellers moving through a city’s streets and public spaces at different times of day. Jacobs likens the complex order of a lively city sidewalk to “an intricate ballet in which the individual dancers and ensembles all have distinctive parts which miraculously reinforce each other and compose an orderly whole.” Design Workshop’s emphasis on the open studio as a space of creation and invention where team members encounter and engage with each other to develop new designs borrows from this idea. Members of the team and their varied skills and experiences concentrate in the studio and complement each other.i

Steven Johnson discusses the phenomenon of “collective intelligence” in Emergence: The Connected Lives of Ants, Brains, Cities, and Software (2001),leading off with an example of an ant colony which is often misunderstood to be governed by the queen, a single individual who issues directives. In fact the decision-making and social coordination of an ant colony are made collectively .Through random encounters, individual ants are keenly aware of each other’s movements and actions. What emerges from their interactions is a self-organizing system for solving larger problems within the colony. Johnson also focuses on cities as emergent systems. Like Jacobs, he shares a fascination with sidewalks,which “mix large numbers of individuals in random configurations” and foster the local interactions and exchanges of information that in agglomerate into “complex order” at the city scale. The place-making focus of Design W orkshop’s practice –the engaging public spaces the f rm implements outside its walls – has been applied to the studios in which designs are developed. They are the public spaces of the company where design teams interact and solve problems collectively. They are central to Design Workshop’s conception of itself and to fostering the teamwork that is necessary to tackle complex projects.ii

Many companies today are exploring how to create work environments that spur interaction and innovation. The common work spaces of international design f rm IDEO are a frequently mentioned example as are the corporate campuses of Silicon Valley such as Pixar Animation Studios and Facebook. And there is a proliferation of articles and business books that attempts to address the value of collaborative efforts and the context and conditions for making them successful. In The Wisdom of Teams: Creating the High-Performance Organization (2006), Jon R. Katzenbach and Douglas K. Smith pro f le companies that form teams for research, productivity,and idea generation and also explore why many other organizations overlook the potential of group ef forts or implement them inef fectively.iiiSimilarly, Maverick: The Success Story Behind the W orld’s Most Unusual W orkplace (1993)captures the story of the Brazilian company Semco, the family business of Ricardo Semler, who transformed the organization through unorthodox practices that increased innovation and productivity while simultaneously changing existing company culture.iv

Since its founding over forty years ago, and in advance of many recent books and offices exploring the optimization of the work place, Design W orkshop has had strong notions about optimal settings for collaboration. Beyond the open studio areas that are central to each of f ce are individual work spaces, and corner of f ces are nowhere to be found. Instead, staf f members of varying seniority are dispersed in non-hierarchical arrangements of desks. In this scenario, conversations are overheard and information is ef f ciently disseminated across all staf f levels. Such close access (and proximity)to design principals is edifying for less experienced staff, and the intermingling of staf f with diverse roles, knowledge, and expertise reinforces the collaborative nature of the off ce’s workshop atmosphere.

Collaboration means many things at Design W orkshop. It can mean working side by side with someone who sits a few desks away, or it can mean sharing f les and work efforts with a colleague in another state or country. Some project teams are composed of staff members from several of Design Workshop’s six off ces based on the need for a particular expertise or someone’s availability to help on a deadline.Inter-office and client collaboration is made possible through audio, web, and video conferencing systems. Technology enables design conversations to span the distances between off ces throughout the United States and with clients across the globe, bridging the distances so that inter-of f ce teams can be deployed to get the work done. It ensures that one of f ce can easily reach out to another, and it avoids the isolation that characterizes many other f rms with multiple locations.

Design Workshop’s management structure defies the hierarchy typically found in a corporate setting. An employee stock ownership plan provides staf f with an ownership interest in the f rm and reinforces a mentality that everyone contributes to its success. Monthly billing and revenue projections are shared with everyone at the f rm, from the person who answers the phone to senior staff. Off ce scorecards paint a picture of each of f ce’s health and show not only f nancial performance such as revenues, backlog and utilization but also the number of design reviews and recent awards won which are indicators of design iteration, excellence, and of f ce visibility.This philosophy and unusual level of transparency are grounded in the ideas covered in The Great Game of Business: Unlocking the Power and Profitability of Open-Book Management (1994), which promotes an open-book management approach where employees are empowered by information and feel a sense of ownership and accountability to the performance of the operation.vThere is an entrepreneurial attitude among staff at Design Workshop, and the proof of the value created by instilling this spirit can be seen in the dif ferent areas into which the f rmhas expanded over the years. For instance, golf course design and Development Services, the group that provides market analysis and strategic development planning for clients, were both launched by individual employees who were driven by a passion and interest in these areas of professional consultation and were able to prove the f nancial viability of expanding the f rm’s services into these areas.

图4 (fig.4)CREDIT:DesignWorkshopDesign Workshop’s comprehensive DW Legacy Design ® approach ensures that projects are environmentally sensitive, community supported, economically sustainable and artfully executed.DesignWorkshop的DWLegacyDesign®方法确保项目是对环境敏锐的、支持社区的、经济的可持续发展的以及可产生艺术效果的。

图5 (fig.5)CREDIT:DesignWorkshopDesign Workshop’s method diagram provides an outline for a comprehensive approach to the project, as well as how the design will be iterated and evaluated. DesignWorkshop的方法图给项目提供了一个综合性方法的轮廓,以及如何迭代和评估设计。

Borne of Academia

The Workshop name and the way the firm operates stem from experiences its founders had as academics prior to starting a design f rm. During a teaching stint at University of North Carolina in the late 1960s, Joe Porter and Don Ensign saw a need to work around areas of specialization that separate and stif e collaboration between academic and professional disciplines. In 1969 they opened their practice with two other professors from dif ferent academic departments for the purpose of creating a “workshop” where educators from across the university, people from industry and students could collaborate without barriers. The f rm was named “Design Workshop” to describe a culture of people working in collaboration.

Although Joe Porter is now retired from the firm, his intentions in creating Design Workshop are as fresh now as they were at the f rm’s inception. Recalling recently the genesis of the f rm, Porter noted that “Silos exist in business, law, design, architecture,landscape architecture, engineering, finance, and other disciplines and special interests responsible for creating built environments and maintaining ecosystems.These silos are born and nurtured in academia where scholars are rewarded for becoming expert in a single subject and digging deeper and deeper into that subject at the expense of collaboration and connecting disciplines. Forming a company based on the concept of a workshop was an attempt to get people from different sectors to work together toward common goals. Tackling complex planning and design problems requires thinkers from dif ferent disciplines. The way to get them to collaborate is to base the design exercise on shared values and principles.” (see f g. 3)

A Principle-based Practice

Design Workshop’s practice is defined by four principles - comprehensiveness;inclusiveness; transparency; and knowledge - that are necessary for collaboration and rigorous design solutions. The first principle, comprehensiveness, is best expressed by the overlapping Legacy Design rings. (see f g. 4)

This principle of developing design solutions is achieved through four essential aspects of sustainability – environment, community, economics and art. These focus areas form the interlocking rings of the firm’s DW Legacy Design®method. Every project represents an opportunity to balance goals in all four areas to achieve projects that are environmentally sensitive, community supported, economically sustainable and artfully executed. The complexity of the projects undertaken by Design Workshop requires a quadruple-bottom line approach to be truly sustainable.vi

The second principle, inclusiveness, defines Design W orkshop’s approach to generating ideas developing designs. The business of place-making involves soliciting a broad spectrum of input from the design team, consultant experts, clients and communities.

The third principle, transparency in decision-making, is exhibited by the studio environment and the openness with which groups interact to advance the work.Exposing the goals of a project and the basis of decisions is edifying to all participants and aligns the team.

The fourth principle is knowledge. Design Workshop places great importance on project-based research that leads to knowledge development and design innovation.Evaluating the performance of projects enables a team to test design strategies,expand expertise and determine whether further innovation is possible.

A Formalized Design Approach

Design Workshop has been guided by the process-oriented ideals related to comprehensiveness, inclusiveness, transparent decision-making and knowledge since its founding. However the leadership of the firm decided to formalize this principle-based design approach at a shareholders retreat in the late 1990s. To operate in a truly collaborative manner, to be participants in a workshop, design teams need to follow a shared methodology. DW Legacy Design®outlines a comprehensive, transparent, rigorous and iterative process to the work. A method diagram was developed to serve as a design roadmap for the staff. (see f g. 5)

The diagram depicts how every project is launched with a strategic kick-of f meeting to lay the foundation for how the team will perform the work and engage the client and stakeholders. During this session, the team embarks on an exercise to discover the opportunities and challenges faced by the project and to set comprehensive inquiries that inform project-based research and the establishment of performance goals. Following academic practices, teams develop a project challenge statement(called the Project Dilemma)and a hypothesis statement (called the Project Thesis)for each new project. Developed collectively by the team, the Project Dilemma aligns the group around impediments to a successful design solution. The Project Thesis posits a vision for the f nal design and serves as a constant reminder of the outcome the team is aiming for.

A spirited session at the beginning of each project defines goals that balance economic concerns, community values, environmental issues and the art of design into a cohesive vision for the project. The goals beget research assignments, and team members are deployed to delve into the topics that are relevant to the project.Further inquiry enables the team to anticipate measureable performance bene f ts the implemented project will deliver. Outlining this initial process of design discovery,collaboration and accountability provides a pathway for the team and is essential to the success of the project.

图7 (fig.7)CREDIT:D.A.Horchner/DesignWorkshopEvery project is launched with a strategic kick-of f meeting during which the design team collectively identif es topics that are relevant to the project and identi f es environment-, economic-, community- and art-related goals for the design to achieve. 每一个项目都推出一个战略启动会议,期间,设计小组集体确定与项目相关的主题,并确定环境、经济、社区和艺术相关的设计目标,并实现这些目标。

Rapid Cycling

A central element of DW Legacy Design®is the concept of Rapid Cycling,represented by the looping line on the left side of the method diagram. Rapid cycling is the process of iteration that is central to the f rm’s design practice. Designs are not linear exercises; they evolve. Design W orkshop’s projects are complex and site-specif c. Designs are developed in controlled cycles which combine periods of exploration with cathartic moments when the work must be reined in, consolidated,and presented to the client for feedback. DW’s Chairman of the Board, Kurt Culbertson, adds “Rapid cycling can also be thought of as a process of moving back and forth between two modes of thought – creative and critical. The loops in the diagram depict the process that we go through as designers – we try something, we learn, try something else, and learn something new.” This mode of experimenting in professional practice is termed “Reflection-in-Action” by M.I.T. social scientist Donald A. Schön, who identifies in the design process three distinct approaches to rigorous iteration: exploration; move testing; and hypothesis testing.viiAt Design Workshop, the number of cycles the project undergoes is dependent on its scope,schedule and fee – and the team’s assessment of the design’s quality and level of completion. Tackling the design in this way, and going so far as to represent it on a diagram, instills in staf f the importance of iteration. Design teams are expected to work intently for periods but also to pause periodically to accept outside points of view. How the design evolves and advances is a crucial piece of the collaborative culture of the f rm.

One way that teams can solicit objective feedback to inform a design is through design reviews, a mainstay of the studio and ultimately the test of a healthy workshop environment. Design reviews come in many dif ferent forms. Some occur in regular project meetings where the conversation is limited to the team members wanting to update each other on the evolution of a design. Others take place at individual desks when perhaps a principal who has been traveling wants to check on a project’s progress. But the center of the workshop is an off ce- or f rm-wide design review that is convened to solicit a broad spectrum of objective critique. In these instances, the full off ce gathers over lunch to hear a short presentation by the team.Pizza is provided in exchange for input. Design reviews are held for many purposes:to seek feedback on designs, to share client reactions to a recent presentation and get direction on next steps, to prepare for an interview for a new project, and/or to share a draft of an awards submittal. Such design reviews are part of a deliberate process of critical thinking that is intended to set the stage for further creative inquiry. (see f g. 6)

Knowledge Generation

Staff members at Design W orkshop often talk about what it means to be engaged in a critical practice. By this, they mean being aware of global issues that af fect the built environment, if not the earth and entire human race. The slide show presented at quarterly orientations to welcome new employees to the firm includes a 2007 cover of Newsweek which features a globe on to which is mapped a grid of images depicting politics, paleontology, finance, art, popular culture, science and others.The headline states, “The 181 Things You Need to Know Now.” The purpose of sharing this image with new staf f members is to instill in them the importance of looking beyond the scope and physical boundary of a particular project and to open their eyes to a broad set of in f uences that affect the built environment in general and the project site in particular. The emphasis on expansive lines of inquiry and synthesis of multivalent information is at the core of a comprehensive DW Legacy Design®approach.viii

Design Workshop project teams often seek to learn about topics and incorporate them into designs that a generation ago might have seemed beyond the scope or capacity of a typical landscape architecture practice. There is a complexity to the f rm’s projects that forces its teams to acquire a broad set of information and tools to design and evaluate success. In addition to focusing on the physical design of space and form giving, a typical team might be calculating the ratio of jobs to housing of a master-planned community in an attempt to reduce the number or length of car trips generated by the development. They might be looking into issues of social justice,or making sure that a project’s community engagement strategy acknowledges subsets of the af fected population with tailored surveys. Or they might be studying the retail vacancy or vehicle accident rates in a district to understand and measure impacts before and after a streetscape re-design has been implemented. Being a critical practice is about operating intelligently and with a high level of awareness of the broad issues that inf uence the built environment.

Embracing the complexity of its typical projects, Design W orkshop has embarked on an effort not only to gather information to aid design decisions and inform the best practices of the f rm but also to conduct formal research that generates new knowledge for the profession.ixAs part of this undertaking, project teams increasingly use evidence-based design to measure the performance of the projects during design and after implementation. Shortly after a contract is signed for a new project,the assigned team gathers to identify all the relevant issues and opportunities that will affect the design and its implemented outcome. Menu sheets of research and metrics topics are reviewed and prioritized. The key question that hovers over the group in this initial conversation is, “What story do we and our clients want to tell about this project?” Asking the question at the beginning of the design effort and imagining the outcome helps to shape the agenda of the project. This conversation generates a comprehensive outline and the issues and opportunities become environment-, community-, economic- or art-related research topics and goals that are assigned to different members of the team. (see f g. 7)

Throughout the design process, the project team evaluates the design against set goals. The measurable goals set at the beginning are a tool for evaluating design alternatives over the course of the project. At this stage, a design is not yet realized so it can only exhibit evidence of success. Proof of success is not possible until after implementation when performance assessments can be conducted. Few design f rms have the ability to take on this ef fort themselves which is why Design W orkshop has enthusiastically participated in the Landscape Architecture Foundation (LAF)Landscape Performance Series Case Study Initiative (CSI). This program pairs practitioners with academic teams who produce rigorous studies that measure the sustainable landscape performance benef ts delivered by the built project. Partnering with academic teams, as Design Workshop has done with Utah State University for the last three years, ensures that projects are studied objectively and claims are validated with scientif c methods.The studies are published on the LAF website as a resource for the profession to advance its sustainable practices. Additionally, the academic teams publish the research in peer-reviewed publications and present them at conferences, such as the Council of Educators in Landscape Architecture (CELA).

?

Essential to the expectation that knowledge must be generated in the context of projects and exchanged among project teams is the Design W orkshop portal,an internal website for sharing knowledge and information across the firm. The portal is the place where a range of items is posted for all to see, from employee marriage announcements and of fice social gatherings, from best practices for conducting public meetings to new methods for reducing impervious surfaces. Much of the information is contained in internal topic-based web pages, one of which exists for every DW Legacy Design®metric topic. From Urban Heat Island Ef fect to phytotechnologies to bioswales, these on-line web pages collect information from within and beyond the f rm, including examples of benchmark goals, design strategies, on-line calculators, links to organizations with expertise on the topic,articles, white papers, and exemplary projects. The portal also provides a home for f rm-wide communities of practice which gather staf f who share a common design interest or who are charged with advancing the firm’s capabilities in a particular area, such as digital representation or green roof design. To work at Design Workshop is to be a member of a networked community that values knowledge, and everyone is expected to contribute to the expansion of this knowledge.

On-going Learning

Design Workshop places tremendous emphasis on continuous learning - both for the professional development of staf f and for the infusion of new ideas and expertise into projects. Expecting staff to augment their expertise and to share it with colleagues to advance the practice is part of the f rm’s academic-based composition. This focus on learning happens through formal f rm-wide programs and also in the context of projects.

Design Workshop’s Five-Year Plan for staff outlines the expectations of staf f during their f rst f ve-years at the f rm to expand their knowledge and credentials to build successful and satisfying careers. The Plan def nes goals and timelines for building essential skills, demonstrating thought leadership, pursuing graduate studies and accomplishing professional licensure and certif cation. A graduate degree is required to advance to a leadership position. The f rm strongly believes that the pursuit of a graduate degree is a transforming experience that results in increased con f dence,intellectual and personal maturity, and professional capacity. Staff are encouraged to present at conferences and to publish articles. The goal of the Five Year Plan is to outline a process that develops young talent as quickly as possible in an organized rather than random pursuit. Design W orkshop’s emphasis on the development and sharing of knowledge, and on solidi f cation of knowledge through certi f cations and degrees, is an attempt to hasten an employee’s passage from novice to master.Semiannual performance reviews are milestones that enable each employee to measure progress against professional development goals.

A series of lunchtime presentations by internal staf f and guest experts is planned for each year. Held several times a month, the “Lunch and Learn” series of fer short presentations about topics that are relevant to design, speci f c types of projects, or general skill-building. Staff members from all of f ces connect to a web conference to hear the presentations and to participate in the discussions at the conclusion of each lecture. Recent topics have included stormwater management, urban street trees, phytoremediation, public art, digital modeling, meeting facilitation, project management and GIS.

Since 2006, Design Workshop has convened over ten f rm-wide symposia on topics or project types that are areas of focus for many at the f rm, including urban corridor design, planting design, new community development, park design and community comprehensive plans. When several Design W orkshop offices are working on the same types of projects, a session is convened so that teams can share best practices. An outside guest is invited to serve as the keynote speaker and to frame the discussion. Several project teams grappling with similar issues are invited to participate in short presentations to share best practices and to receive feedback.While participating in symposia removes staf f from pressing deadlines and billable capacity for a portion of a day, f rm leaders believe these sessions expand awareness of best practices in the industry, improve project designs, and strengthen the bonds across off ces. They reinforce the notion of “workshop.”

The firm’s conviction that connecting staf f to knowledge and teaching them how to conduct project-based research will advance the practice has led to travel and exploration beyond the con f nes of DW’s six off ces. From 2005 to 2007, the entire f rm traveled to annual retreats in dif ferent cities in the United States. The focus of the 2005 gathering in Las Vegas, Nevada, was Design Methods. In 2006, staff visited Portland, Oregon, where the focus was on Environment and Art, which form two of the DW Legacy Design®categories. Community and Economics were the focus of the 2007 meeting in Chicago, Illinois. These conference-like gatherings of fered lectures, break-out sessions, and tours of exemplary urban projects and were led by internal experts and guest presenters with particular insights about comprehensive sustainable practices achieved in the built environments of the cities visited. (see f g. 8)

“Working at Design W orkshop is like being back in school,” says Josh Brooks,who recently joined the firm after graduating with an undergraduate degree from Louisiana State University’s Robert Reich School of Landscape Architecture in Baton Rouge. “I really appreciate all the learning events that are of fered throughout the year. The frequent design reviews infuse the studio with a sense of inquiry and critique that sets the tone for design exploration.”

Connecting to Academia

As a firm borne of academia, Design W orkshop has maintained close ties to design programs in numerous American universities and with individual professors throughout the country. Utah State University’s landscape architecture program has been designated as the recipient of the f rm’s off ce archives. For several years, the f rm has hosted a Faculty-in-Residence program in which a professor is invited to spend time at one or all of the f rm’s off ces while on a sabbatical or summer break.The mutual benef ts of these arrangements are tremendous. For the academic, the opportunity brings exposure to professional practice and time to apply research to projects that will be implemented. Interacting with a faculty member af fords staff the chance to learn directly from an expert with deep knowledge in a particular subject.Academic visitors tend to feel at home in the studio due to Design W orkshop’s process-oriented design practice and shared methodologies for pursuing design solutions. Bruce Ferguson, the Franklin Professor of Landscape Architecture at University of Georgia School of Environmental Design and an expert on stormwater design and technologies in the United States, experienced two summers at Design Workshop and Les Smith, professor of landscape architecture at Ball State University, spent several months at Design W orkshop during a sabbatical to reinforce the intersection of art making and design. (see f g. 9)

Design Workshop sponsors two programs that bridge the gap between academia and professional practice. The f rst is Design W eek, during which a principal and several staff members partner with the faculty of an undergraduate landscape architecture or planning program at a rotating list of universities to host a weeklong charrette focused on a site-specif c design problem. After teaching the students about comprehensive design processes, interdisciplinary teams are formed to focus on a complex design problem. Volunteering time to interact with students and teach them about rigorous professional practice is invigorating for the firm’s staff and forges new relationships with faculty members and academic institutions. Academics and students are exposed to the workshop approach promulgated by the f rm and the fruitful outcomes that stem from cross-disciplinary endeavors. To date, Design Weeks have occurred at prestigious design schools including Clemson University,University of Kentucky, Louisiana State University, Texas A&M University and Penn State University. (see f g. 10)

In addition, Design W orkshop sponsors an annual summer internship program.The f rm solicits applications for approximately one dozen internship spots spread across the f rm’s six off ces. Each year, one off ce is designated as the host of an intense multi-day design workshop attended by all of the interns for the f rst week of the summer. The students are immersed in the collaborative culture of the f rm and learn the DW Legacy Design®process. After this stint, each is assigned to a Design Workshop office and spends the remainder of the summer working on the firm’s projects for clients. (see f g. 11)

An Intentional Culture of Collaboration

Design Workshop’s name, physical spaces, comprehensive design philosophy,collaborative design principles and shared methodology continually reinforce the concept of “workshop.” Upholding the culture of collaboration is the responsibility of everyone at the f rm.

Every staff member is a proprietor of the workshop. For the most part, design teams self-organize and initiate conversations to advance concepts in a discovery-oriented environment. However the culture of collaboration must be fostered. To promote the idea of workshop and to inculcate this way of practicing, a team of Legacy Design representatives from each of f ce meets monthly to share new research or ways of evaluating design and built outcomes through performance metrics. They also discuss the condition of the workshop culture in each off ce and take steps to nurture it as needed. If the f ow of design reviews and team work has ebbed in an off ce, these caretakers will encourage the group to change behavior and seek the input of those outside the project team in the common area of the studio. In other cases an inter-off ce design review may be scheduled to stimulate communication and sharing ideas across the f rm.

Jane Jacobs wrote that “Without a strong and inclusive central heart, a city tends to become a collection of interests isolated from one another. It falters at producing something greater, socially, culturally and economically, than the sum of its separated parts.”xVital urban spaces are created when diverse systems, uses and people overlap and engage. Applying this thinking to a design studio, the concentrations of designers and circulation of diverse viewpoints are crucial to the life of the studio as a place where knowledge is generated and solutions to complex design problems are produced. The highest quality of design can be achieved by the contributions of a team in a workshop rather than by individuals acting alone. At Design Workshop, this condition is cultivated daily and intentionally to uphold the culture that was central to

the f rm’s founding and to the way it continues to operate today.

Notes:

i Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York, NY: Random House, 1993, 227; 65.

ii Steven Johnson, Emergence: The Connected Lives of Ants, Brains, Cities, and Software. New York, NY:Scribner, 2001, 74; 31-33; 94; 96.

iii Jon R. Katzenbach and Douglas K. Smith, The Wisdom of Teams: Creating the High-Performance Organization. New York, NY: First Collins Business Essentials, 2006.

iv Ricardo Semler, Maverick: The Success Story Behind the World’s Most Unusual Workplace. New York, NY:Business Plus, 1993.

v Jack Stack with Bo Burlingham, The Great Game of Business: Unlocking the Power and Prof i tability of Open-Book Management. New York, NY: Currency/Doubleday, 1994.

vi This expands on the concept of triple-bottom line accounting that integrates ecological, social and economic criteria into measures of organizational success. Design Workshop adds a fourth key area – Art – into the formula.

vii Donald A. Schön, The Ref l ective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. New York, New York: Basic Books, 1983, 146-147.

viii “181 Things You Need to Know Now,” Newsweek (July 2, 2007): Cover Image. This double issue of Newsweek collected essays on global topics about which readers need to be knowledgeable to navigate the increasing complex world and to achieve, what editor Jon Meacham termed, “Global Literacy.”

ix See M. Elen Deming and Simon Swaffield, Landscape Architecture Research: Inquiry, Strategy, Design.Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2011, 239-242. Deming and Swaff i eld discuss the diversity of knowledge development and research in the context of landscape architecture practice and introduce three realms of knowledge development – 1) Integrating research strategies into practice; 2) Integrating research into practice –polemical transformation; and 3) Integrating Knowledge into Practice – Grassroots Movements.

x Jane Jacobs, The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York, NY: Random House, 1993, 215.

About the author:

Allyson Mendenhall is the Director of the DW Legacy Design®, Design W orkshop’s comprehensive and sustainable design practice. She develops tools and models for research in Design W orkshop’s practice of landscape architecture, urban design and land planning, and teaches the methodology which emphasizes performance measurement of the f rm’s built work. Allyson is distinguished for her project leadership of largescale, complex, multidisciplinary design and planning ef forts. A graduate of Harvard College and Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD), Allyson serves on the GSD Alumni Council and also on the Board of Directors of the Landscape Architecture Foundation.