Huizhou Woodcarver and Inheritor

By staff reporter JIAO FENG

HUIZHOU, renamed Huangshan in 1987, has for centuries been a main cultural and economic hub. Anhui merchants and businesses were prominent in Chinas economy from the 14th to 19th century, and fundamental to formation of Huizhounology, which along with Dunhuangnology and Tibetology is one of Chinas three main regional cultures. Traditional Huizhou woodcarving is manifest in embellishments to house beams, screens, window lattices and balustrades, as well as tables, chairs, cabinets and beds. An infl uential school in the history of Chinese folk woodcarving it is, along with Huizhou stone and brick carving, known as one of Huizhous “three carvings.”

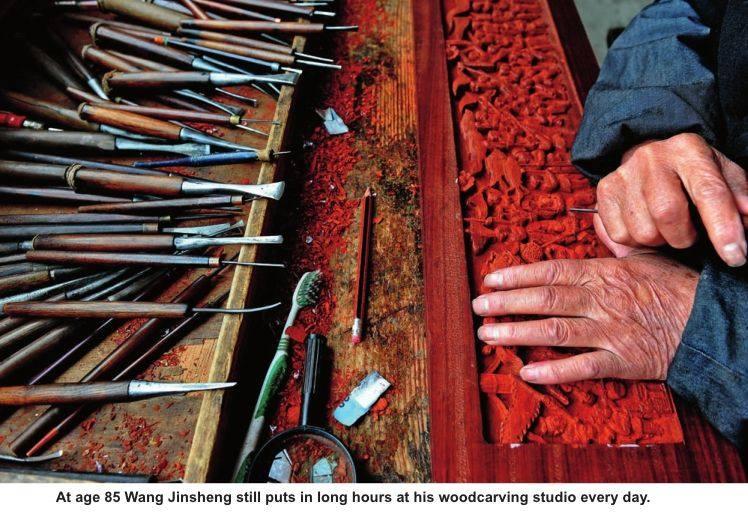

Wang Jinshengs vitality belies his 85 years. He ushered us into his studio, where two of his apprentices were busy on one bench, while semi-fi nished works stood on another. Besides teaching apprentices each day, Wang also creates his own carvings. Working at what most interests him keeps him both mentally and physically fi t.

Apprentice to a Woodcarving Master

Wang Jinsheng told us about his life as we sat in his austere living room.

A sickly child, Wangs parents put him under the tutelage of celebrated Huizhou woodcarving master Wang Xulun. Their motive was to train him in a skill that would obviate heavy manual labor on reaching adulthood. “Having been raised in a home environment rich in artistic carvings, I had an innate admiration for them and so was happy with my parentsarrangement,” Wang told us. Wang was proud of his master, who attended the fi rst National Conference of Outstanding Workers as representative of Huizhou woodcarving, and had his photo taken with Marshall Zhu De.

During his time as an apprentice Wang and his master applied their skills to refurbishments of ancestral halls around Huizhou. Working under strict guidance of his teacher laid a solid foundation for Wangs later achievements.

Years of hard work enabled Wang gradually and comprehensively to master the art of woodcarving. In 1951, he was transferred to Hefei, capital city of Anhui Province, where he worked at the Hefei Arts and Crafts Factory. Other than Wang Jinsheng and one other novitiate, all workers at this new factory were seasoned craftsmen. Wang nonetheless stood out by virtue of his obvious talent. He participated in all major events of the factory, notably creating woodcarvings for the fi rst agricultural exhibition in Beijing after the founding of the PRC. Seven years later in 1958, when the Great Hall of the People was under construction in Tiananmen Square, he was again dispatched to Beijing to do woodcarvings for the buildings Anhui Hall.

Shezhou Inkstone Revival

The four treasures of the study – inkstone, calligraphy brush, inkstick and rice paper – were essential aspects of the daily life of venerable scholars. Shezhou inkstone is regarded as the most precious. Owing to wars during the early 20th century, production of Shezhou inkstones ceased and did not resume until the founding of the PRC in 1949.

“In the early 1960s, the Anhui provincial government assigned me the task of reviving Shezhou inkstones. Despite generally hard times, the government allocated the funds I and my team needed to carry out research,” Wang Jinsheng recalled. It was during this decade that Wang was transferred back to the arts and crafts factory in Shexian County.

His first task was to locate the source of raw material for the inkstone. After studying historical records, Wang and his fellows traveled to Yanshi Mountain in Wuyuan of Jiangxi Province, where rock quarrying had stopped decades earlier. They next studied the craft of inkstone carving. With the benefit of deep knowledge and decades of practice in woodcarving, they carried out explorations and trials of its various shapes and styles. “We rubbed and carved day and night. Intent on making the finest possible inkstones, we were immersed in our work.” Wang and his team finally succeeded in both creating and innovating Shezhou inkstones.

In 1967, the 12 samples of Shezhou inkstones Wang and his colleagues had produced went on exhibition in Shanghai. Eleven of them were particularly admired by foreign businesspeople, and soon went into mass production. “That marked the first time Shezhou inkstones became known in the market, and before long they were in high demand. Years later, Chinese leaders on state visits abroad would present Shezhou inkstones as national gifts to their foreign counterparts, and people in their thousands visited the Shexian County Arts and Crafts Factory to observe the manufacturing process,”Wang Jinsheng said.

Wang then turned his attention to what he perceived as the unsightly packaging of these delicate artifacts, using his expertise to give the wooden boxes in which inkstones were presented greater aesthetic appeal. His endeavors and high skills won his colleagues admiration, and the epithet “Master Jin” (golden master).

Large Relief Woodcarving of 500 Arhats on Mt. Lingshan

In 1982, then 55-year-old Wang Jinsheng reached retirement age. But due to his irreplaceable expertise, he was asked to carry on working for a few more years. Even after finally retiring in 1987, Wang carried on doing woodcarvings at home. His son encouraged him to go out more and enjoy his retirement with other elders, but Wang insisted that carving was his preferred recreational activity.

Wangs innovations to traditional woodcarving added to them greater artistic value and hence collectibility. Many collectors came to him offering high prices for his works, but Wang stuck to his rule of taking all the time he needs to finish a piece of work. In other words, no matter what price was offered, he declined to abide by a deadline. As he explained, “Woodcarving is an art similar to painting. You need to take the time necessary to put your heart and soul into it by working through any artistic inclinations that might arise. Unless I can do my work to the best of my ability I would rather not do it at all.”

In 2001, the Buddhist Art Museum at the Lingshan Grand Buddha Scenic Area in Wuxi City, Jiangsu Province took the decision to commission a relief woodcarving of the 500 Arhats (Foe Destroyers). Twelve pieces of 2,000-year-old silkwood were selected for the carving. The expense and high significance of this work made choosing a carver a crucial task. Feng Qiyong, then in charge of this project, appointed a team to find the right person. Finally, on the recommendation of the Huangshan Painting and Calligraphy Academy, the task was assigned to Wang Jinsheng.

“When Feng Qiyong came to me I was dismayed to learn I would be working on a total 12 pieces of precious antique wood. As I had never carved on such a large scale before I was afraid I might ruin these raw materials, so told Feng I would first try working on one piece,”Wang said. When Wang showed his finished carving to Feng Qiyong he “thought highly of it, saying that he could see in it the essence of Huizhou woodcarving, and so regarded it as authentic Huizhou art.” The remaining 11 pieces of wood were then taken to Wang Jinshengs home. One thing worth mentioning is that silkwood has an extremely hard texture that calls for great strength in the artists wrists as well as fingers. High expertise, persistence and experience thus also define the quality of these carvings.

The 1.7-meter-high, 42-meter-long relief woodcarving, 500 Arhats Hall on Longevity Hill, effectively replicated a painting by Wang Fangyue in 1757 depicting Emperor Qianlong (1711-1799)supervising the building of the hall on Longevity Hill in the Yuanmingyuan, or Old Summer Palace. Unfortunately the painting was destroyed when the AngloFrench allied armies burned the palace down in 1860. Wangs woodcarvings act as a memorial to it.

Self-endowed Legacies

The year 2007 marked the end of the three years Wang Jinsheng took to finish two woodcarvings (9 m x 0.5 m) replicating the Northern Song Dynasty painting Qingming Festival at the Riverside. Each carving includes more than 500 figures. A collector purchased one; the other remains in Wangs studio, along with woodcarvings celebrating the painting One Hundred Horses by Lang Shining (Giuseppe Castiglione), court painter to the Qing Emperors for half a century, and certain other of his works. Relieved at successfully finishing Qingming Festival at the Riverside and having worked all his life for other people, Wang elected to keep these and other lovingly crafted works for himself.

Wang Jinsheng has waited two generations for a suitable heir to his wood carving expertise. His son did not inherit his skills, and it did not seem appropriate to teach woodcarving and the hard manual work it entails to his granddaughter. But Wangs great-grandson, now 24, has been learning the craft from him for six years. Wangs apprentices also reap the benefits of his skills and experience, along with students at the local vocational school where he gives classes. Wang has confidence in all his inheritors. He brought our meeting to an end with the remark, “Huizhou woodcarving has been passed down from our ancestors. I hope more people will get to know and love it, and that more master woodcarvers will appear.”

Profile:

Wang Jinsheng, inheritor of Huizhou wood, brick and stone carving, was born in 1928 in Shexian County in southern Anhui Province. He started learning woodcarving skills at the age of 16 from Wang Xulun, a Huizhou woodcarving master. Wang worked on the woodcarvings in Anhui Hall, a part of the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, and also contributed to the revival of Shezhou inkstones. His works have been widely collected by art lovers throughout the world, and presented to foreign dignitaries as national gifts. Among many others, Feng Qiyong, acclaimed expert on the classic novel A Dream of Red Mansions, has commended Wang Jinsheng as authentic inheritor of Huizhou woodcarving.

pot luck

Steamed Pork with Royal Fern

Shangluo City of Shaanxi Province in northwestern China, nestled between its namesakes Shanshan Mountain and Luoshui River, is one of the cradles of Chinese civilization, inhabited by early humans as early as the Paleolithic age over one million years ago. The areas rolling mountains produce a fernlike plant, shangzhi (Osmuna regalis), which is used in various dishes by local residents. In the springtime the plant emerges suddenly from the sleeping earth, and when the purplish red sprout grows to about 20 cm, with tender leaves that curl like chicken claws, locals harvest them, dry them in the sun either as they are or after blanching them, and preserve them for cooking.

Four hermits are given credit for the plant having entered local diet. The lived at the turn of the Qin and Han dynasties in the second century BC, during which time the notorious Qin emperor, Qinshihuang, gave the order to burn books and bury hundreds of scholars alive. To escape persecution, four pundits named Zhou, Wu, Cui and Tang fled to the mountains of Shangluo. They lived there until Liu Bang, founder of the following Han Dynasty (206 BC- AD 220), sent them repeated invitations to join his bureaucracy. They refused, but to help crown prince Liu Ji, they served as Liu Jis political advisers. As a result, the emperor dared not depose Liu Ji and pass on power to another son. After Liu Ji ascended the throne, all four returned to the mountains and resumed their former reclusive lives.

Though from time to time food would run short, the four hermits remained in good shape throughout the harsh years in the mountains and all lived long lives. During their days in the wilderness, they discovered a plant they later named shangzhi that was delicious and inspired them to write about it in a poem. Many attributed their health and longevity to this plant, and it soon found its way onto the table of local families.

Method:

Braise a piece of streaky pork, slice and stack on a salver. Immerse dried royal fern in hot water, clean and shred the upper seven to 10 cms of the plant. Place royal fern on top of the meat, sprinkle with spices and minced shallot and ginger. Steam for half an hour over a high flame. Enjoy the succulent pork and royal fern in a combination that is believed to stimulate digestion and nourish the inner organs.