Mt.Qiyun,Home of Taoists

MY friends and I headed to Anhui Province last spring to climb the Yellow Mountain. As a tie-in trip we also headed to the neighboring Mount Qiyun, a Taoist holy site.

Mount Qiyun is most often mentioned as a footnote to the Yellow Mountain, which is one of Chinas “big fi ve” mountains. But it turns out that Mt. Qiyun is no less impressive than its famous brother in terms of both natural scenery and cultural signifi cance.

The two mountains are close to each other– a distance of mere 50 kilometers. Both fall within the territory of Huangshan City. Qiyun in Chinese means “as high as the clouds,”though the mountain doesnt really live up to its name – it reaches a modest 585 meters above sea level.

The appellation is not entirely baseless, however. For much of the year the mountains 36 craggy peaks are shrouded in a sea of clouds and a dense veil of mist in the morning. The clouds, it seems, descend from the heavens to fulfi ll the promise of the mountains name.

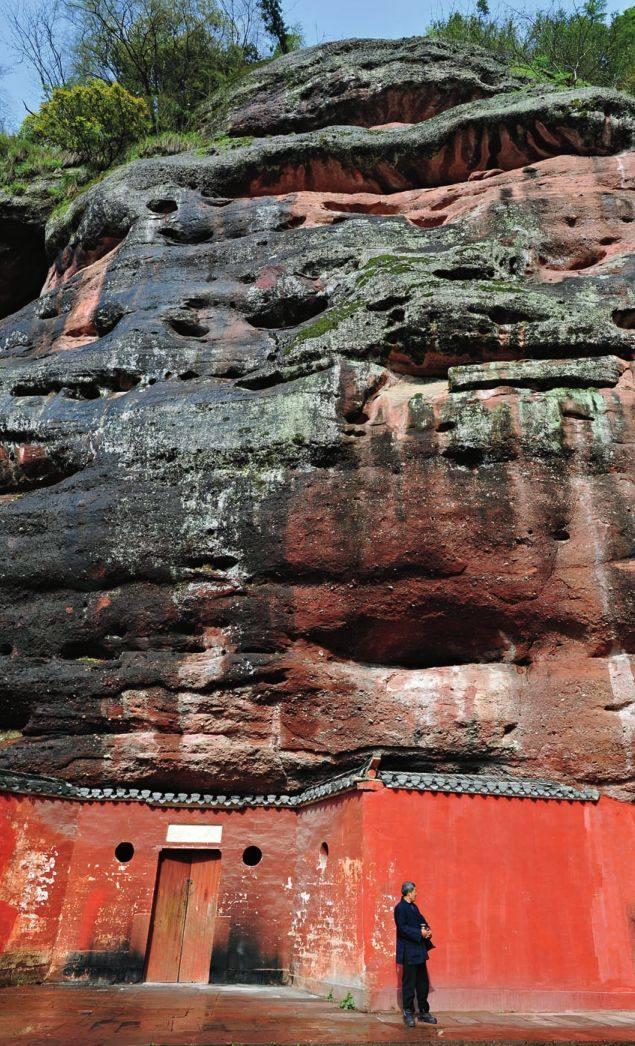

Perhaps the almost constant cloud cover and the sense of seclusion it creates explain why Mount Qiyun has remained an epicenter of Taoism in South China for over a millennium. Chinas history over the past several hundred years has been tumultuous, but this hasnt stopped Taoist followers from making pilgrimages to the mountaintop shrine of Lord Zhenwu, the Truly Martial Grand Emperor. Dynasties fell and wars raged, but artists, scholars and poets continued the Taoist tradition of immersing themselves in the serene solace of the woods above Qiyuns steep bluffs. Some have left behind works of art to mark their stay in the form of inscribed tablets. The carvings of sages long past remain on the rock face today, standing stately guard over tourists who clamber up Qiyun.

Land of Immortals

Mt. Qiyun sits on the bank of the Shuaishui River which, viewed from the mountaintop, meanders along picturesquely by grain fields and white-walled cottages. The river and its polychrome surrounds are said to closely resemble a black and white Yin and Yang sign – or the “diagram of the supreme and ultimate” to use its real name – when viewed from directly above. Proximity to such powerful Taoist imagery is the reason why Taoist sage Zhang Sanfeng is said to have spent his last years on the mountain before gaining immortality. Thanks to the power of the Tao, Zhang had a long life. According to legend, he lived 200 years from 1247 to 1458.

There is a tomb dedicated to Zhang Sanfeng at Qiyun – but its empty. According to Chinese myth, on ascending to heaven ones corporal remains vanish without a trace in the temporal world.

My friends and I arrived at Qiyun in the afternoon. To save time we decided to give up the idea of scaling the mountain on foot, which would take about three hours if we took the shortest route, and opted for the cableway.

As our gondola rose higher and higher, our view of the surrounding land broadened. Below us rapeseed fields were in full blossom, lending a golden splash to the riverbanks and valley floors. Scattered among the yellow were clusters of cottages constructed in the style typical of the area– white walls and dark tile roofs. It was an idyllic picture of the countryside, and one that seemed –to us in our gondola, at least – untouched by time or trend.

Reaching a lower peak, we hopped out of our cablecar and found ourselves at the Wangxian(Watching the Immortals) Pavilion. Following our guide, Mr. Wang, we walked down the Peach Blossom Valley towards Dongtianfudi, the Taoist appellation for the “residence of immortals” that literally means “a sacred spot concealed from the outside world.” There are many Taoist sites in China of the same name, but this one stands out due to its abutting the Peach Blossom Valley. Such a valley is a metaphor for Lost Paradise in Chinese.

Dongtianfudi is the site of Zhang Sanfengs tomb. Also in the area are three examples of fine cliff carvings at the Xizhen, Zhonglie and Shouzi rock faces.

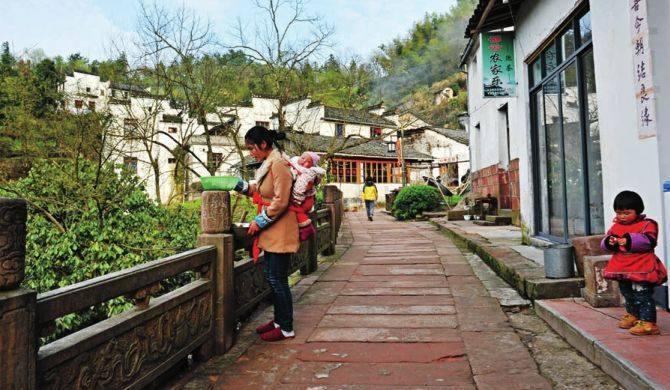

Mr. Wang is from one of the mountains traditional Taoist families. His grandfather and father were both abbots at a local Taoist monastery, and he is a pious believer himself. Wang sees Mt. Qiyun as different from other Taoist holy sites. For one, it is open to both religious and secular communities, and non-Taoists reside alongside the faithful in the mountains villages. This mixing can be best seen along Yuehua Street, where a motley collection of buildings – some cloisters, some residences and some plain old shops –jostle for spiritual and commercial customers.

Almost all visitors make a stop at the Mengzhen Bridge in Peach Blossom Valley. Many tie a yellow ribbon on its stone rails after making a wish. Mengzhen actually translates as “a dream coming true” in Chinese. The bridge leads to a flagstone path built during Ming Dynasty Emperor Zhengdes reign (1506-1522). Mosses grow on the stones, undergoing centuries of pilgrimstreading.

Hermits and Deities

According to Wang, in former times Taoism was popular among those who wished to escape the commotion of worldly life by seeking refuge in sequestered mountain caves for meditation. Most Taoist shrines are built on mountains for this reason. The reputation of Mt. Qiyun historically drew in many believers and practitioners who spent long years holed up in grottos on the mountains cliff faces.

An indigenous religion that began to form into a comprehensive philosophical system about 1,900 years ago, Taoism is believed to have its origin in worship of gods and ghosts in prehistoric times. Its believers practice alchemy, exercise their breathing rhythms and meditate, among many other activities, in the hope of eventually gaining immortality. The central tenet of the religion is harmony between man and nature, and between the mind and the body.

Taoism has a syncretic mix of gods, which are mostly borrowed from a mélange of local cultures and traditions. Some Taoist historical figures have also been canonized and subsequently worshiped.

Among the ranks of gods are those that watch over other “planets” such as the sun and the moon, those who assume natural formations like mountains and rivers, as well as those who manipulate specific aspects of our daily life, including the God of Kitchen. Many gods are revered by all Taoist followers; others are native icons of specific regions, and their influence and worshippers remain localized.

This great diversity and inclusive spirit is present on Mt. Qiyun, where shrines can be found to the Eight Immortals of Taoism, the goddess in charge of fertility, the Eighteen Arhats from Buddhism, Lord Zhenwu, the guardian of Mt. Qiyun, and the folkloric Dragon King and the God of Learning. Qiyun represents a truly remarkable confluence of Chinas major philosophical systems.

Cliff Carvings

The visitors to Qiyun over the course of history, many of whom were artists and scholars, have left their mark on the mountain. The most ambitious among them would have their writings engraved on the cliff faces of Peach Blossom Valley and other scenic – and sacred – spots.

According to Mr. Wang, such carvings could be found at 1,000 locations in the past, but only 538 have been preserved to date, with the oldest dating back to the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127). The loss can be attributed to a number of causes. Some later visitors scratched off the old inscriptions to make way for their own writings, and harsh weather conditions higher up the peaks have resulted in considerable erosion.

The carvings are generally poems, records of events and religious scripts. Writers were often officials, artists and intellectuals. Some were renowned in their respective fields; most were not. In judging the artistic merit of the carvings, handwriting is important, but chiseling into rock is an equally demanding skill. Anhui Province boasts some of Chinas best stonecutters, who over the centuries have developed a distinct carving style of their own. The abundance of experienced hands is the reason why such a large number of cliff carvings can be found on Qiyun. Carvers would come here to prove their mettle, and make money.

During one of his inspection tours of southern China, Qing Emperor Qianlong (1711-1799) was fascinated with the sights at Qiyun, and made an inscription for the mountain: “Unraveled beauty on earth, Number One mountain in the south.”

Town in the Air

Climbing up Mt. Qiyun is pleasant, as the slope is gentle. There were not many tourists the day we visited, which made our experience all the more special. The giggles and shouts of a group of high school students were the only distraction as we headed along the mountain path.

Soon after we passed Santian (Three Heavens) Gate, a crescent-shaped hamlet emerged at the end of the vista halfway across the peak in front of us. “Thats Yuehua Street!” A friend shouted with excitement.

Yuehua (Moonlight) Street is actually a community of Taoists and their families. Taoists are generally celibate, but the local sect, Tianyi, allows marriage. Theyre not even required to be vegetarian. In fact, their material lives dont differ much at all from those of locals living beyond the cloisters.

There are several Taoist temples in the wider village, the most revered being Taisu Palace, built at the order of Qing Emperor Jiaqing (1760-1820). Local residents, professional Taoists and their families have embraced commercialism and tourism as a source of income – some have opened home stay businesses and restaurants for pilgrims and the wider public. Its highly recommended to spend a night in the village. Locals say the moon looks so close at night, and the gathering mist envelops the whole area to such an extent in the morning that visitors could be mistaken for believing they are in a fairyland.

Unfortunately we were on a tight schedule and had to conclude our tour within the day. “After water fills the cup, it begins to spill over; when the moon reaches fullness, it begins to wane.” As this Taoism maxim says, there is no perfection in this world, and the best we could do was follow the natural course of life and be happy. Our lot, it seemed, was to move from Qiyun that day. But we all agreed wed return.

Scenic Spots:

Taisu Palace:

Taisu Palace is a spectacular complex measuring 1,600 square meters, built at the order of Qing Emperor Jiaqing. The original building was destroyed in the 1960s and a reconstruction project was launched in 1994. Following a formal prayer ritual, it opened to the public in 1997. It stages Taoist observances from the first day of the seventh lunar month to the first day of the tenth lunar month every year. The session starts with a three-day fast for all members of the local monastery, followed by a prayer session for the blessing of God Xuantian for the monastery and all local Taoists. One of the biggest events in the period is on the 19th day of the sixth lunar month, which is believed the date when the Goddess of Mercy achieved immortality. A lavish celebration is held on this day, on which almost all followers in the region gather at the temple. The smoke from the incense they burn envelops the mountain.

Xianglu (Incense Burner) Peak:

The small peak facing the Taisu Palace. It resembles an incense burner, and rises directly in front of the temple, giving it superstitious significance.

Xiaohutian:

A cavern on a bluff behind a stone gate tower, hollowed out in the Ming Dynasty(1368-1644). Below is a deep abyss. It is said to be the site where Taoists could achieve immortality when their practice and understanding of the faith had reached a certain point.

Zhulian (Pearl Curtain) Spring:

On a cliff directly below the Zhenxiandongfu a slender flow of water spurts out of nowhere and scatters a myriad of crystal water droplets onto the rocks below, before cascading into the Bilian (Green Lotus) Pool.

Transport:

Mt. Qiyun is about 30 km from Tunxi District of Huangshan City. Shuttles com- mute between the Tunxi Bus Depot and the mountain on regular basis everyday. The drive is about an hour.

Specialty Food:

Locally grown herbs and other produce, such as the purplevine (Wisteria sinensis) flower, bracken, bamboo shoots and ham, contribute greatly to local Qiyun cuisine. A tiny fish from local rivulets and starch extracted from arrowroot (Radix puerariae) roots are also a staple. Indigenous snacks include Jixi Caigao, a steamed spongy cake, Dongmitang, a pop rice candy, and dry Toufu-wrapped shrimps.