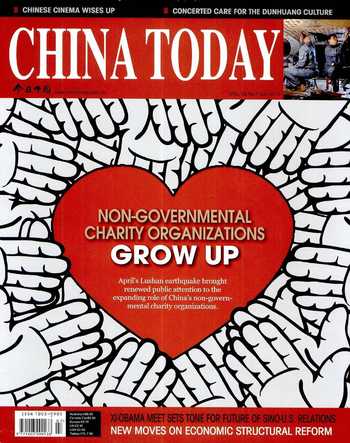

The Ascent of Chinese Charity

By GAO HUAJUN

Charity on a Daily Basis

The emergency response to the Yaan earthquake last April highlighted the strides that NGO rescue and aid capabilities have made since the Wenchuan earthquake of 2008. Among them is Kung Fu star Jet Lis One Foundation, which has established a nationwide disaster relief network.

NGOs first appeared as a new force for disaster relief after the Wenchuan earthquake of 2008. In the five years since, NGOs, with support and encouragement from the government, have become stronger and more influential.

Three aspects exemplify their progress. The first is the amount of donations that NGOs raise – the figure was RMB 30.9 billion in 2007, soared to RMB 107 billion in 2008 and, after a dip in 2009, again surpassed the RMB 100 billion mark in 2010 – and the growth of registered foundations, private nonenterprise organizations and social organizations from 38,690 at the end of 2007 to 489,000 in 2012. Second is the emergence of influential private foundations engaged in public welfare programs, and the expansion of their fundraising capacities. These foundations have acted as pilots for the establishment of a modern charity system. Third is the growing public participation in public services, apparent in the dramatic increase in private small-sum donations, and the tens of millions of people who now work as volunteers.

The steady influence and change that micro public welfare has wielded in China has been integral to developing this cause. Easy Internet access and the thriving use of automated multi-media terminals constitute an economical, speedy tool for both exchanging information and making donations. The resurgence of volunteerism and growing awareness of social responsibilities have also brought more Chinese people to the understanding that everyone can do his or her bit for the public good.

This type of welfare is easy to disseminate and makes public welfare accessible to all social sectors. But to be successful it must be both well organized and appropriately guided. Take the One Foundation as an example. It operates a system whereby individuals donate one yuan each month through the support of various payment platforms, such as Unionpay, Tenpay, Alipay, Paypal, and Quick Money. The foundation is widely accepted among the public and claims to have been the biggest collector of small-sum donations in the aftermath of the Yaan earthquake.

An effective charity, however, demands more than just good will. Certain individual volunteers and small public service organizations that operated after recent earthquakes lacked the professional knowhow and technical support vital to disaster relief. Also the capacity to communicate with local governments and cooperate with larger NGOs. Such small outfits impose on limited resources, so adding to the burden of local residents to no avail. Integrating micro public welfare into the countrys modern charity network eliminates these fundamental problems.

NGOs and Government Work Together

The Guo Meimei scandal, when a young woman claiming to be general manager of a company affiliated to the Red Cross Society of China boasted on her blog about her luxury lifestyle, plunged the countrys largest charitable group into a crisis of trust. Although later investigations showed that the story about her job and fabulous possessions was pure fantasy, years later the organization is still struggling to clear its name.

But crises such as this that public welfare organizations with government backing face should be considered objectively. The public service environment has since changed dramatically, undoubtedly as a result of public calls for reforms amid the rapid development of public welfare.

Government backing endows many advantages on such public service organizations. They include a far-reaching network of professionals in all fields and the accumulated benefits of a long-established professional system. On the other hand, these organizations are large in scale and long established, and have consequently developed certain path dependence. This makes them unwieldy and slow to respond to dramatic changes while at the same time occupying a disproportionate share of resources. Sweeping reforms, therefore, are imperative to cut red tape and revitalize the system. The China Foundation for Poverty Alleviation is one example of success in this respect. It has carried out reforms to privatize and marketize its human resources and streamline management, so making it a modern system designed for charitable causes.

In addition to the threat of trust crises, NGOs also face demands for information transparency and public supervision. To perform their duties properly, both NGOs and charitable organizations with government backing are expected to be professionally equipped and organized. They must be committed to capacity building while maintaining a sound administrative structure and standardized, transparent operations.

That NGOs have achieved greater public trust than their government-affiliated peers signifies the fast development of Chinas charities, the end of the transitional period, and structural changes that have made way for a new charitable environment. This, however, is not to say that NGOs necessarily surpass government-supported organizations as regards administration, information dissemination and other factors.

The public has pressed for restoration of the nongovernmental aspect of charitable organizations, in expectations of a more autonomous, free-spirited voluntary institution. But from a long-term perspective, charitable organizations need government support and encouragement. Over the past three decades of opening up and reform, Chinas economic aggregate has ranked a world number two, with a per capita GDP of US $6,000. This has led to a higher demand for public services.

In its new round of reforms with the consistent aim of improving living standards and promoting social inclusion, the government needs to cede certain implementation powers and functions to social organizations. It should purchase their services, focusing on essential public services of strategic and national significance. The government should, in effect, work together with the public. Certain services, like care for children, seniors and the disabled, early education, and psychological counseling can be provided by public service organizations rather than government agencies. The former could offer specialized professional services in the capacity of government auxiliaries.

Private charitable organizations should enter into smooth, all-embracing cooperation and communication with the government. Such teamwork is essential for better understanding of public policies, social development plans and social demands; also of fields of government investment that produce wellplanned strategies and comprehensive services. The free lunch program for rural schoolchildren is proof of the importance of this cooperation. The program was initiated in Hunan with both NGO and government support. The State Council national nutrition plan for rural students followed closely on its heels. A platform has since been established with an annual investment of RMB 16 billion from central finance.

Needed Professionalism

Modern philanthropy started in developed Western countries. It has evolved into carefully constructed systems characterized by high professionalism. Among them, those of the U.S. are the most developed. Prominent examples are the Rockefeller Foundation and the Carnegie Foundation, both of which have set out to serve humanity and improve society for more than 100 years.

China can learn much from these organizations, particularly how they have both endured and prospered, since they not only spend but also earn money. These entities have, through the operations and investments of elite heads of different generations, accumulated wealth while setting up and funding charities, thus creating a benign development cycle.

Bill Gates, Warren Buffet and other new magnates and philanthropists have inherited charitable activities and made them worldwide social missions. Inspired by the innovative Silicon Valley spirit, charitable concepts and modes such as venture philanthropy, impact investing and social entrepreneurship, among others, have been established. Scores of community foundations in the U.S. apply local resources to solving social problems through their efficient, wide-ranging and well-organized fund-raising modes.

Chinas philanthropy, in comparison, is at an early stage. The public is not familiar with modern charity. Certain policies impede the progress of public service foundations and other social organizations by requiring them to pay tax, in the same way as commercial companies. Tax is also payable on donations of stockholders equity. Public foundations must, in addition, pay out 70 percent or more of donations to charitable causes received in the previous tax year, as compared to the eight percent exacted from private ones. It is no wonder that philanthropists in China say that foundations may be allowed to be established here, but not to grow.

Meanwhile, the public does not assent to the combination of public service and business, nor acknowledge that charitable organizations could make money. The fact is that revenue could be cyclically channeled into charity. Some public service organizations are not familiar with marketized investment operations, and there is a shortage of foundations specialized in both aid and everyday operations. They are moreover small in scale with weak capabilities. All these flaws need to be remedied without delay.